27 Nov 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, France, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features

Editorial Credit: Frederic Legrand – COMEO / Shutterstock.com

Even before the attacks on Paris on 13 November were over, French President Francois Hollande declared a nationwide state of emergency giving authorities additional powers in the name of protecting citizens and combatting terrorism. But since the attacks, concerns have been raised for press freedom prompted by the cancellation of a regular radio segment by journalist Thomas Guénolé.

A few days after the events of 13 November, Guénolé devoted his daily morning commentary piece on RMC radio to what he perceived as the failings of the French security services and police. On the same day, the Interior Ministry called Philippe Antoine, RMC managing editor, to demand the radio station air a corrective to points Guénolé discussed during his segment, which the ministry would pen. “Interestingly, the corrective was not going to appear as a corrective emanating from the Interior Ministry but as the correction of an inaccurate information emanating from RMC,” Guénolé told me.

The proposed corrections were in relation to Guénolé’s discussion of claims reported by various news outlets, including that France had known since August 2015 that IS planned to attack a rock concert in France and that Turkish authorities had warned France twice this year about Omar Ismaïl Mostefaï, one of the assailants of the Bataclan massacre.

Guénolé called for a parliamentary investigation which should, if these claims were true, prompt the resignation of the highest ranking French officials, including Bernard Cazeneuve, France’s Minister of the Interior.

Guénolé also repeated information published by La Lettre A, which claimed only three out of 50 members of the Parisian Brigade de recherche et d’intervention (an anti-gang unit, which is to intervene in hostage situations) had been on duty after 8pm on the night of the attacks. On 19 November, the special adviser to France’s interior minister, Marie-Emmanuelle Assidon, took to Twitter to say the information contained in La Lettre A was false but recognised she had not read the article. “[N]o one but Thomas Guénolé trusts your info,” she added in her tweet.

“I have repeatedly asked Place Beauvau for a denial,” Marion Deye, editor at La Lettre A, told me. “I haven’t had one.” Neither have Le Monde or the AFP, also quoted by Guénolé.

“We published a very factual piece of news on the Monday following the attacks, at a time when any type of criticism was not welcome,” Daye said. “However, what we published was not a criticism, just a report. The most absurd thing in this whole story is that no one knows what Place Beauvau denied when they spoke to RMC. I think what was really problematic for some was that Guénolé brought up the resignation of Cazeneuve.”

On Friday 20 November, Guénolé was informed that his daily column was cancelled. In an email, the RMC managing editor wrote: “The Interior Ministry and all the police services invited on air have refused to appear on RMC because of inaccuracies in your column. Most sources of our police specialists have gone silent since Tuesday, putting in jeopardy the work that our editorial team does to find and verify information.”

Guénolé described the actions against him as both a “boycott” and an “embargo”.

“One would expect a media outlet to back up its journalist and not to have too strong a dependency vis-à-vis institutions,” he said. “My particular case doesn’t matter so much. What is unacceptable is that the Interior Ministry seems to have pressured RMC because they were displeased with what a journalist said on air in the context of the state of emergency.”

The firing of Guénolé happened on the on the same day the Assemblée Nationale voted to extend the state of emergency from 12 days to three months. Measures to control the press were initially proposed by 20 socialist MPs led by Sandrine Mazetier on the basis that the coverage of the January 2015 attacks in Paris – especially by news channel BFM-TV – had endangered the life of hostages who were hiding in a Hyper Casher supermarket. Such a measure would be highly problematic. As Mathieu Magnaudeix, a journalist with the investigative website Mediapart, put it to me: “If we were to end up with an authoritarian power, which by now doesn’t seem to be out of the question, what could they do with a law that allows the control of the press?”

Thankfully, the press control measures were later dismissed and it was made clear that even Hollande was strongly opposed. Regardless, it is apparent journalists still aren’t safe.

The proposed law does, however, extend and harden house arrests that are allowed under a state of emergency, enables members of the police force to carry their weapons while off duty, gives stronger powers to the authorities to carry police searches that are not approved by a judge. While these cannot be carried out in the workplace, police searches can take place at the house of an MP, lawyer, a judge or a journalist.

This kind of anti-terror legislation, as we have seen in the UK, could have further negative consequences for journalists covering terrorism.

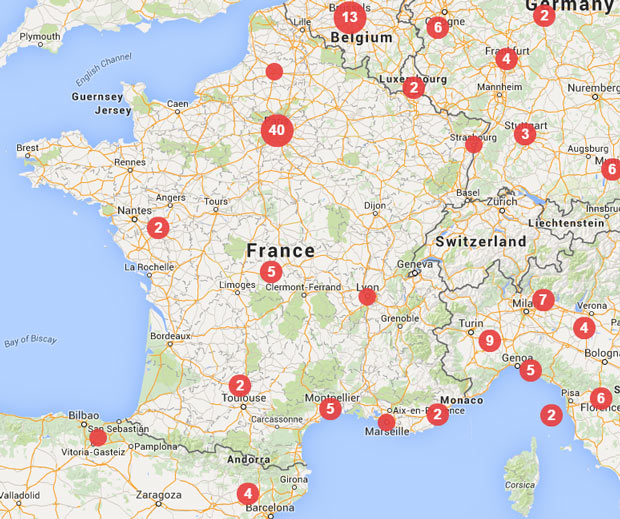

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

2 Nov 2015 | France, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features

Vincent Bolloré is known for business takeovers. Now 63, he has built an empire in energy, agriculture, transport and logistics.

The billionaire is also a media mogul with expanding interests. His investment group Bolloré, named for its president and CEO, has a majority share in Havas, a leading French advertising and PR group. It owns the cable television channel D8 and the daily newspaper Direct Matin.

Bolloré was appointed as president of Vivendi, the French mass media company, in June 2014. Vivendi owns Canal Plus, a French subscription-based television channel known for its irreverent tone, where Bolloré became chairman last September.

A common theme is emerging in Bolloré’s professional life. As he attains more media companies, there are increasing attacks on editorial content he disapproves of. Last June, Le Canard Enchaîné revealed that Havas, a French multinational advertising and public relations company, which is controlled by the Bolloré group, had cut the advertising budget in Le Monde by €3.2 million in 2014 and €4 million in 2015. This followed the publication of two articles that Bolloré disliked — a personal profile and a report on the activities of the Bolloré group in the Ivory Coast.

“It can be hard to understand whether a media owner is doing something to improve the health of his business or whether he is meddling with editorial content,” says Virginie Marquet, a lawyer who specialises in freedom of the press and co-founder of the collective Informer N’est Pas Un Délit (To Inform Is Not A Crime). “What’s new with Bolloré is the brutality of what is taking place.”

Pierre Siankowski is the former culture editor for Le Grand Journal, a primetime talk show which was broadcast on Canal Plus every weekday and produced by independent production company KM. On 3 July, he found himself out of a job when Bolloré personally decided KM would stop producing the talk show. “The reason given is that the show was too expensive and that Bolloré wanted it to be produced internally,” Siankowski says. “But there’s actually an article in Le Parisien that claims the current cost of production is roughly the same.”

For Siankowski, there may be another reason. He says Renaud Le Van Kim, producer of Le Grand Journal, who is believed to have been made to leave the company he created at Bolloré’s demand, and Rodolphe Belmer, former director of Canal Plus who was fired in July, had both expressed support for Les Guignols De L’info — a satirical news bulletin broadcast on Canal Plus where politicians are played by latex puppets — amid rumours the show was under threat.

The puppets are currently in the closet, having been temporarily taken off the air. The show is due to return in November, but on Bolloré’s orders, it will have more of an international focus, and therefore less coverage of French politics. It may also lose its prime-time slot.

Does Siankowski think the attack against Les Guignols might be politically motivated? Is it a gift from Bolloré to Nicolas Sarkozy, who was a frequent target of the show? “Here is what we know: after he got elected, Sarkozy went on holiday on Bolloré’s yacht,” he says. “We also know Sarkozy hated Les Guignols, and that in a few months’ time the political campaign for the presidential election will start.”

Meanwhile at Canal Plus, there were other worrying signs. In July, it was revealed that a documentary on tax evasion at the Crédit Mutuel bank — one of the main financial partners of the Bolloré group — which was scheduled to be broadcast on Canal Plus in May, had been removed from the programme before it was supposed to air. Geoffrey Livolsi, co-director of the documentary, said Belmer had received a phone call from Bolloré, who requested it be axed following a conversation with Michel Lucas, CEO of Crédit Mutuel.

When asked by staff representatives to explain the decision, Bolloré allegedly replied: “You don’t kill your friends.”

The documentary was finally shown on France 3 in October.

In September,another documentary, this time on the rivalry between Sarkozy and French President Francois Hollande, was taken off Canal Plus grid without explanation, before reappearing a month later.

“What this shows is that we don’t have the tools that are needed to protect press freedom,” Marquet says. “This is why we felt we need to mobilise.”

“What we would like to see are sanctions,” Marquet adds, reminding us of the existence of a resolution voted in 2013 by the European Parliament. It states: “Governments have the primary responsibility of guaranteeing and protecting freedom of the press and the media” and considers “the trend of concentrated media ownership in large conglomerates to be a threat to media freedom and pluralism”.

Bolloré’s attack on the media isn’t confined to those organisations in which he has an influence. He has taken legal action against journalists and publications to defend his business interests. His group has sued, among others, rue89, France Inter, Libération and Bastamag. It also took journalist Benoît Collombat to court over an investigation he had done on the group’s activities in Cameroon.

Asked what he thought of “the Canal Plus spirit” on 12 February on France Inter, Bolloré replied: “It’s a spirit of discovery, of openness, sometimes of excessive derision.” On that same evening, Les Guignols featured Bolloré’s puppet, who was asked to define what “acceptable derision” means. It seems the real life billionaire’s answer to that question has been clear.

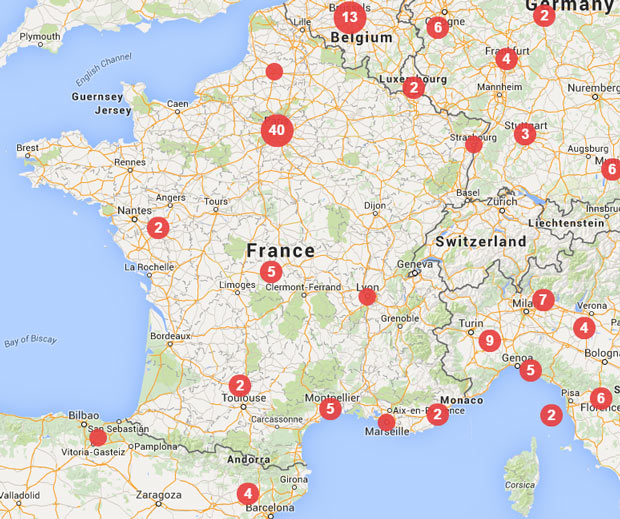

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

8 Jan 2014 | Comment, France, News and features, Religion and Culture

It’s coming up to the seventh anniversary of the death of Hrant Dink. Just today, two people have been arrested in connection with his assassination.

It’s coming up to the seventh anniversary of the death of Hrant Dink. Just today, two people have been arrested in connection with his assassination.

Dink, a Turkish-Armenian journalist, understood censorship and free speech more than most. In Turkey, the Armenian genocide of the early 20th century remains taboo, and discussion of it can result in charges under the infamous article 301 of the country’s criminal code – the crime of “insulting Turkishness”.

Recognition of the genocide is an important part of Armenian identity, and many Armenians in the the country itself, Turkey, and the wider diaspora were pleased when, in 2006, French politicians proposed a law making denial of the Armenian genocide illegal. But Dink, understanding that censorious laws hurt everyone, dissented, saying:

“As you know, I have been tried in Turkey for saying the Armenian genocide exists, and I have talked about how wrong this is. But at the same time, I cannot accept that in France you could possibly now be tried for denying the Armenian genocide. If this bill becomes law, I will be among the first to head for France and break the law. Then we can watch both the Turkish Republic and the French government race against each other to condemn me. We can watch to see which will throw me into jail first”

Dink was assassinated, and the bill was blocked, though it reared its head again in 2012, only to be deemed unconstitutional.

One wonders what Dink would have made of president Francois Hollande’s bid to ban public performances by comic and political activist Dieudonne, inventor of the “qeunelle” gesture – an inverted Nazi salute dressed up as an “anti-establishment” gesture. Dieudonne, who ran on an “anti-Zionist” platform in the last election, says there is nothing anti-Semitic about the quenelle, a claim undermined by the spread of pictures of smirking fans quenelling near synagogues, holocaust memorials and even outside the Marseilles Jewish school where three children and a religion teacher were shot down in cold blood in 2012.

It’s important to be clear on this: the quenelle is an anti-Semitic gesture. Dieudonne’s defenders, such illustrious figures as Diane Johnstone and Alain Soral (what we might call the Counterpunch Left), will claim that it is not.

But that is because they are defending Dieudonne’s views, rather than Dieudonne’s right to free speech. It’s an important distinction. Too often, we either attempt to defend free speech by downplaying what’s actually being said (“it’s not that bad”), or claiming it’s something that it’s not (“this isn’t actually racist; it’s, er…”)

Similarly we attempt to justify shutting down free speech by saying something is not a matter of free speech, or worse, resorting to the fact of an existing law or prevalent social mores rather than making a moral argument (as Bernard-Henri Lévy did while discussing the Dieudonne case on theBBC’s Today programme).

A genuine defence of free speech demands that we look what’s happening directly in the eye.

The quenelle is anti-semitic. Dieudonne is anti-semitic. Dieudonne has a right to free speech.

Hrant Dink would have understood that.

It’s coming up to the seventh anniversary of the death of Hrant Dink. Just today, two people have been arrested in connection with his assassination.

It’s coming up to the seventh anniversary of the death of Hrant Dink. Just today, two people have been arrested in connection with his assassination.