31 May 2024 | Israel, News and features, Palestine

The following article was first published by +972 Magazine, an independent, online, nonprofit magazine run by a group of Palestinian and Israeli journalists. Index on Censorship has reported on media freedom on both sides of the conflict since the 7 October attacks.

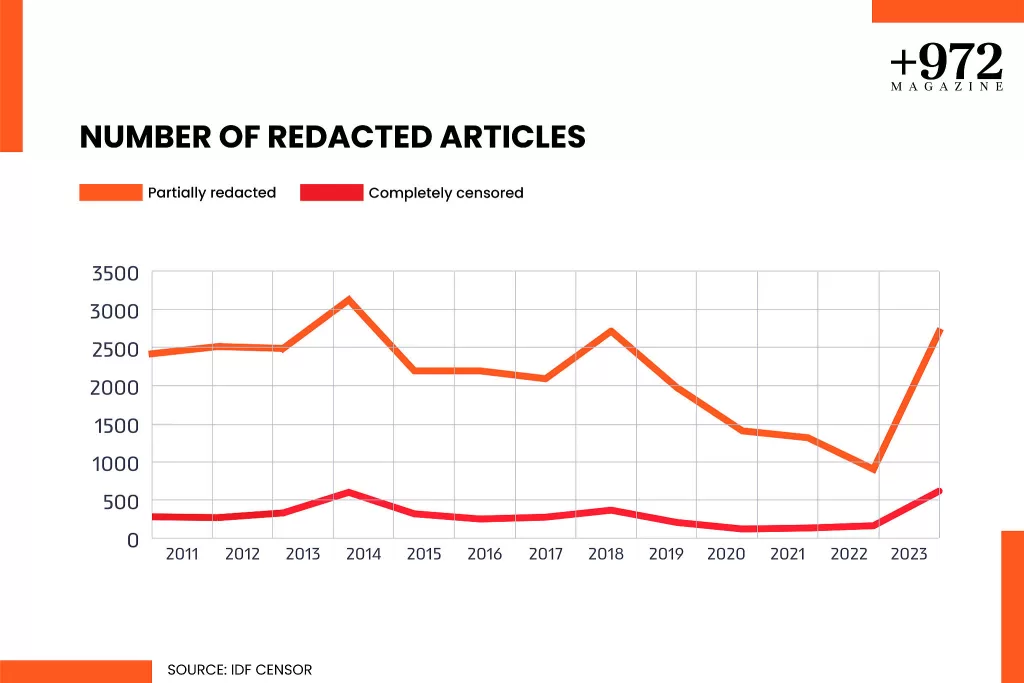

In 2023, the Israeli military censor barred the publication of 613 articles by media outlets in Israel, setting a new record for the period since +972 Magazine began collecting data in 2011. The censor also redacted parts of a further 2,703 articles, representing the highest figure since 2014. In all, the military prevented information from being made public an average of nine times a day.

This censorship data was provided by the military censor in response to a freedom of information request submitted by +972 Magazine and the Movement for Freedom of Information in Israel.

Israeli law requires all journalists working inside Israel or for an Israeli publication to submit any article dealing with “security issues” to the military censor for review prior to publication, in line with the “emergency regulations” enacted following Israel’s founding, and which remain in place. These regulations allow the censor to fully or partially redact articles submitted to it, as well as those already published without its review. No other self-proclaimed “Western democracy” operates a similar institution.

To prevent arbitrary or political interference, the High Court ruled in 1989 that the censor is only permitted to intervene when there is a “near certainty that real damage will be caused to the security of the state” by an article’s publication. Nonetheless, the censor’s definition of “security issues” is very broad, detailed across six densely-filled pages of sub-topics concerning the army, intelligence agencies, arms deals, administrative detainees, aspects of Israel’s foreign affairs, and more. Early on in the war, the censor distributed more specific guidance regarding which kinds of news items must be submitted for review before publication, as revealed by The Intercept.

Submissions to the censor are made at the discretion of a publication’s editors, and media outlets are prohibited from revealing the censor’s interference — by marking where an article has been redacted, for instance — which leaves most of its activity in the shadows. The censor has the authority to indict journalists and fine, suspend, shut down, or even file criminal charges against media organizations. There are no known cases of such activity in recent years, however, and our request to the censor to specify its indictments filed in the past year was not answered.

For more background on the Israeli military censor and +972’s stance toward it, you can read the letter we published to our readers in 2016.

“Information pertaining to censorship is of particularly high importance, especially in times of emergency,” attorney Or Sadan of the Movement for Freedom of Information told +972. “During the war, we have [witnessed] the large gaps between Israeli and international media outlets, as well as between the traditional media and social media. Although it is obvious that there is information that cannot be disclosed to the public in times of emergency, it is appropriate for the public to be aware of the scope of information hidden from it.

“The significance of such censorship is clear: there is a great deal of information that journalists have seen fit to publish, recognizing its importance to the public, that the censor chose not to allow,” Sadan continued. “We hope and believe that the exposure of these numbers, year after year, will create some deterrence against the unchecked use of this tool.”

A wartime trend

Although the censor refused our request to provide a breakdown of its censorship figures by month, media outlet, and grounds for interference, it is clear that the reason for last year’s spike is the Hamas-led October 7 attack and the ensuing Israeli bombardment of Gaza. The only year for which there was a comparable level of silencing was 2014, when Israel launched what was then its largest assault on the Strip; that year, the censor intervened in more articles (3,122) but disqualified slightly fewer (597) than in 2023.

Last year, the censor’s representatives also made in-person visits to news studios, as has previously occurred during periods in which the government has declared a state of emergency, and continued monitoring the media and social networks for censorship violations. The censor declined to detail the extent of its involvement in television production and the number of retroactive interventions it made in regard to previously published news articles.

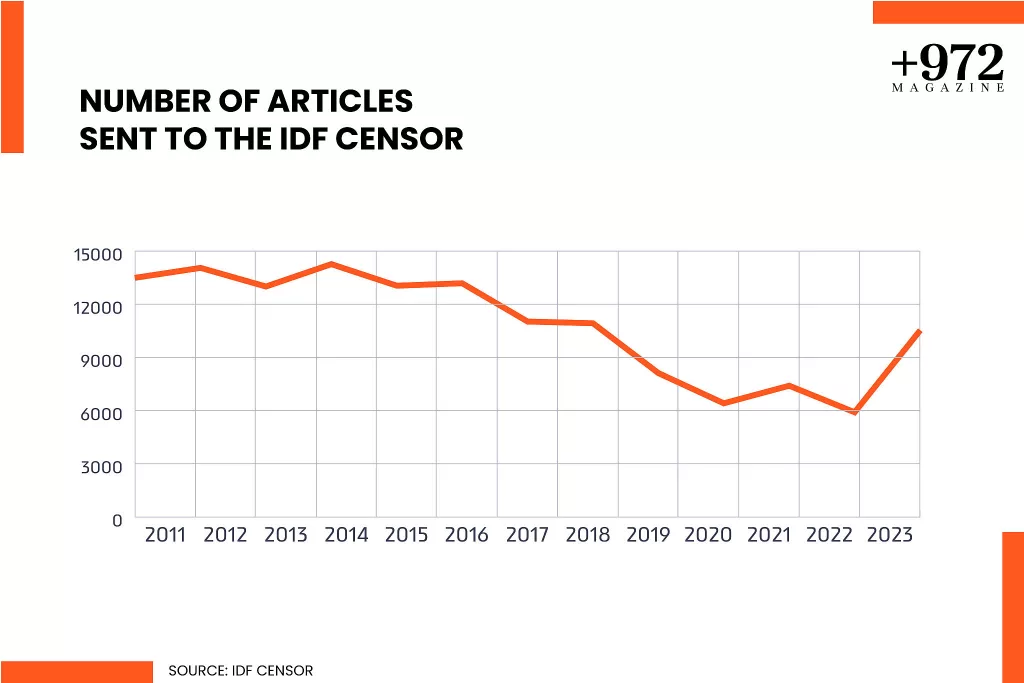

We do know, however, thanks to information revealed by The Seventh Eye, that despite the Israeli media’s proactive compliance — the number of submissions to the censor nearly doubled last year to 10,527 — the censor identified an additional 3,415 news items containing information that should have been submitted for review, and 414 that were published in violation of its orders.

Even before the war, the Israeli government had advanced a series of measures to undermine media independence. This led to Israel dropping 11 places in the 2023 annual World Press Freedom Index, followed by an additional four places in 2024 (it now sits in 101st place out of 180).

Since October, press freedom in Israel has further deteriorated, and the censor has found itself in the crosshairs of political battles. According to reports by Israel’s public broadcaster, Kan, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu pushed for a new law that would force the censor to ban news items more widely, and even suggested that journalists who publish reports on the security cabinet without the approval of the censor should be arrested. The chief military censor, Major General Kobi Mandelblit, also claimed that Netanyahu had pressured him to expand media censorship, even in cases that lacked any security justification.

In other cases, the Israeli government’s crackdown on media has skirted the censor and its activities entirely. Back in November, Communications Minister Shlomo Karhi banned Al-Mayadeen from being broadcast on Israeli TV, and in April, the Knesset passed a law to ban the activities of foreign media outlets at the recommendation of security agencies. The government implemented the law earlier this month when the cabinet unanimously voted to shut down Al Jazeera in Israel, and the ban will now reportedly also be extended to the West Bank. The state claims that the Qatari channel poses a danger to state security and collaborates with Hamas, which the channel rejects.

The decision will not affect Al Jazeera’s operations outside of Israel, nor will it prevent interviews with Israelis via Zoom (full disclosure: this writer sometimes interviews with Al Jazeera via Zoom), and Israelis can still access the channel via VPN and satellite dishes. But Al Jazeera journalists will no longer be able to report from inside Israel, which will reduce the channel’s ability to highlight Israeli voices in its coverage.

The Association for Civil Rights in Israel and Al Jazeera petitioned the High Court against the decision, and the Journalists’ Union also issued a statement against the government’s decision (full disclosure: this writer is a member of the union’s board).

Despite these various attacks on the media, the most significant threats posed by the Israeli government and military, and especially during the war, are those faced by Palestinians journalists. Figures for the number of Palestinian journalists in Gaza killed by Israeli attacks since October 7 range from 100 (according to the Committee for the Protection of Journalists) to more than 130 (according to the Palestinian Journalists Syndicate). Four Israeli journalists were killed in the October 7 attacks.

The heightened government interference in Israeli media does not absolve the mainstream press of its failure to report on the army’s campaign of destruction in Gaza. The military censor does not prevent Israeli publications from describing the war’s consequences for Palestinian civilians in Gaza, or from featuring the work of Palestinian reporters inside the Strip. The choice to deny the Israeli public the images, voices, and stories of hundreds of thousands of bereaved families, orphans, wounded, homeless, and starving people is one that Israeli journalists make themselves.

This article was previously published by +972 here.

5 Apr 2024 | Israel, News and features, Palestine

Almost six months to the day since the outbreak of war between Israel and Hamas, the Israeli government made a decision to shutter the Al Jazeera bureau in Jerusalem. The Knesset vote was an overwhelming 71-10. “The ability of the Communications Minister to shutter press for political motivation is a complete and utter threat to democracy in Israel,” said Noa Sattath, the director of the Association for Civil Rights in Israel (ACRI), Israel’s leading human and civil rights organisation. “We want a journalist to be thinking about the truth, not about what a minister is thinking about them—this is a chilling effect. “

In addition to the attack on freedom of expression and freedom of the press, the new law also effectively precludes the court from intervening in decisions regarding the closure of media outlets. In addition to closing Al Jazeera’s offices, the law allows removing its website and confiscating the device used to deliver its content. Al Jazeera, termed a “propaganda machine” not a news organisation by many in the Israeli government, was an easy target perhaps, especially during wartime, but it is especially in wartime that a democracy’s fortitude is tested.

In a new sixth-month survey of the impact of the war on human and civil rights in Israel, ACRI makes these points: “Even before the terrorist attack Hamas perpetrated on 7 October, and before the war broke out, Israeli democracy was facing severe threats. Combined together, laws designed to take over the judicial system [what Prime Minister and his government called ‘judicial reform’, but what opponents called a ‘judicial coup’ attempt] and a slew of other initiatives in different areas crystallised to produce a judicial overhaul, as part of which the government sought to undermine the pillars of democracy and reduce human rights protections. Some initiatives to take over the judicial system have been put on hold since the war began, partly because this was put forward as a condition for expanding the government [by member parties]. Other initiatives that threaten democracy have also been suspended.”

Yet, there are enough new curbs and potential curbs on human and civil rights to warrant a 14-page document from ACRI. Sattath, the ACRI director, explains: “The government has pushed forward with existing trends such as targeting Arab society, restricting freedom of movement, increasing the prevalence of firearms in public spaces, and accelerating the annexation of the West Bank. Given the general climate in a time of war, these efforts are met with less resistance. In other fields, such as prisoners’ rights, the state of human rights has taken a significant turn for the worse, while the public remains entirely indifferent. Human rights violations are often carried out via emergency regulations (Hebrew), an undemocratic tool that allows the government to enact laws, seriously violating the principle of separation of powers.”

In addition to the actual censoring of media, the mainstream media has self-censored in Israel, aware of—and even setting—the tone among the public. Nightly newscasts cover soldiers in the field, the hostages, and other security concerns but rarely focus on the situation for Palestinians, including the humanitarian concerns in Gaza.

Additionally, people have been detained by the police for a “like” on social media after the Ministry of Justice removed the State Prosecutor’s oversight on charges for offences of freedom of expression during the war, so that police don’t need approval before investigating such cases. Police were directed to detain people for social media posts until the proceedings’ end and prosecute them even for a single publication. This change led to a surge in arrests of Arab citizens regarding social media posts; arresting without cause.

Meanwhile, there is a proliferation of widespread hate speech online incriminating Jewish social media spots promoting hate against Arabs, but enforcement disproportionately targets Arab citizens and residents.

By November, there were 269 investigation cases for incitement and support for terrorism, resulting in 86 expedited indictments for incitement to violence and terrorism. Suspects faced prolonged detention and even remand until trial, a departure from due process.

Additionally, there are significant violations of policing of peaceful demonstrators, along with unlawful detentions of protesters and unauthorised visits to the houses of suspected protest organisers by the police. The police (which is federalised in Israel), led by far-right minister Itamar Ben Gvir, seem to be pre-imagining what steps he anticipates for them and taking them–all with no retribution so far.

Security prisoners in Israeli prisons have faced much worse, with protocols, including lawyers’ visits, upended. Meanwhile, there is a proliferation of guns in the streets with a free-for-all dispensation by Ben Gvir’s office to create private militias both inside Israel and in the Occupied Palestinian Territories where actions by Jewish settlers against Palestinian residents have multiplied.

These are just a few key examples of what Israelis are facing. Even when the war ends and when the current government falls, much of the backtracking in Israeli society will be hard to reverse.

5 Apr 2024 | Israel, News and features, Opinion, Palestine, Ruth's blog

The 21st century has simultaneously brought the world closer together and driven communities further apart. Technological advancements have enabled us to be more aware of the gift humanity can bring to the globe and of our unshaking ability to wreak so much damage.

This dichotomy of hope and hate has been sharply placed into focus in the Middle East.

This weekend marks the six-month anniversary of the horrific 7 October attacks on Israel.

Every night we turn on our televisions and witness the pain and suffering of peoples who yearn for peace.

1,269 children, women and men were brutally murdered by Hamas, with hundreds more tortured and taken hostage. This barbarity ignited a conflict between Israel and Hamas which, as of 5 March, has claimed the lives of 30,228 Palestinians and 1,410 Israelis.

Each person behind these faceless numbers leaves behind a pit of grief for loved ones which will never be filled.

The pain and suffering inflicted by the 7 October attacks have reverberated throughout communities, both in the Middle East and in countries across the planet. The war is leaving behind a trail of devastation and despair. Lives have been lost, families shattered, and entire communities torn apart. The aftermath of such violence cannot be overstated, and the scars it leaves behind run deep.

While Index on Censorship typically centres its efforts on defending freedom of expression, we cannot turn a blind eye to the urgent humanitarian crisis which has unfurled before us. It is crucial that we acknowledge the human toll of such conflicts and recognise the need for immediate action to alleviate the suffering of those affected.

In times of crisis, it is essential that the international community comes together to provide support and assistance to those in need. We must renew our efforts to secure a lasting peace in the region and work towards addressing the root causes of conflict.

This means prioritising humanitarian aid, securing the release of the hostages and ensuring that those devastated by the 7 October attacks receive the assistance they so desperately need. It also means holding accountable those responsible for perpetrating violence and ensuring that justice is served for the victims.

But beyond immediate relief efforts, we must also work towards addressing the underlying issues that fuel such conflicts. This includes addressing issues of inequality, injustice, and discrimination, which often serve as breeding grounds for violence and extremism.

As we reflect on the six-month anniversary of the 7 October attacks, let us not forget the human faces behind the headlines – the families mourning loved ones, the children traumatised by violence, and the communities struggling to rebuild in the aftermath.

As we look ahead, let us honour the memory of those we have lost by working tirelessly towards a future where such senseless violence is but a distant memory. Together, we can create a world where freedom, dignity, and human rights are upheld for all.

15 Mar 2024 | Iran, Israel, News and features, Newsletters, Palestine, Russia

A great privilege of working at Index is, and always has been, the amazing people we get to encounter, those who look tyranny in the face and don’t cower. Iranian musician Toomaj Salehi is one such person. This week, the 2023 Index Freedom of Expression arts award winner donated the £2500 cash prize to relief funds for those affected by the floods in Iran’s Sistan and Baluchistan province in an act of extreme generosity. We were informed of the donation by his family.

Salehi, whose music rails against corruption, state executions, poverty and the killing of protesters in Iran, has spent years in and out of jail. Today he is still not free – indeed he faces a court hearing on another new charge tomorrow. Our work with him doesn’t end with the award. But what solace to know that the money will make a tangible difference to the lives of many and that jail cannot stop Salehi from his mission to make Iran a more just country.

While Salehi, and others, confront the brutal face of censorship, those in the USA and the UK are this week dealing with the finer print – who owns what. The US House of Representatives passed a bill on Wednesday that will require TikTok owner ByteDance to sell the popular video-sharing app or face a total ban. This is challenging territory. TikTok is guilty of its charges, shaping content to suit the interests of Beijing and data harvesting being the most prominent. So too are other social media platforms. If it is sold (which is still an if) we could see a further concentration of influential apps in the hands of a few tech giants. Is that a positive outcome? And how does this match up against the treatment of USA-based X? The social media platform, formerly Twitter, has Saudi Arabia’s Kingdom Holding, the investment vehicle of Prince Alwaleed bin Talal, as its second largest investor. Is the US Government holding X to the same standards?

Meanwhile, the UK government (which has expanded the definition of extremism this week in a concerning way) plans to ban foreign governments from owning British media, effectively saying no to an Abu Dhabi-led takeover of the Telegraph. We have expressed our concerns about the buyout before and these concerns remain. Still, we’d like to see the final proposal before deciding whether it’s good news.

We’ve also spoken a lot this week about the decision by literary magazine Guernica to pull an article written by an Israeli (still available via the Wayback machine here) following a staff-walk out. We stand by everyone’s right to protest peacefully, of which walking out of your office is just that. But we are troubled by other aspects, specifically redacting an article post-publication and the seemingly low bar for such a redaction (and protest), which hinged on the identity of the author and a few sentences. We can argue about whether these sentences were inflammatory – I personally struggle to see them as such – and indeed we should, because if we can’t have these debates within the pages of a thoughtful magazine aimed at the erudite we’re in a bad place.

Speaking of a bad place, Russia goes to the “polls” today.