12 Sep 2019 | Magazine, Magazine Contents, Volume 48.03 Autumn 2019

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”With contributions from Kerry Hudson, Chen Xiwo, Elif Shafak, Meera Selva, Steven Borowiec, Brian Patten and Dean Atta”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

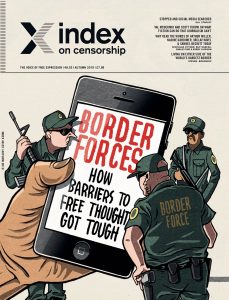

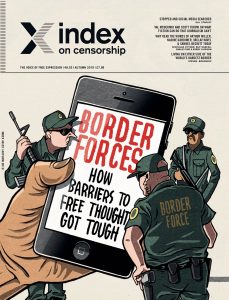

Border forces – how barriers to free thought got tough

The autumn 2019 Index on Censorship magazine looks at how borders are getting tougher, journalists are being stopped, visas refused and border officials are snooping into our social media profiles and personal messages. Nations are looking to surveil our thoughts before allowing us to come into their countries and so limiting freedom of expression and the free flow of ideas.

In this issue Steven Borowiec reports from South Korea about how the law means that you can be prosecuted for contacting your relatives in the north without permission; Meera Selva looks at how internet shutdowns are being used round the world to prevent people communicating, most recently in Kashmir; Mark Frary gives tips for LGBT people on how to protect themselves when crossing borders into countries where they might face discrimination. Charlotte Bailey and Jan Fox look at how it is getting tougher in the UK and USA for artists, writers and academics to get visas; and Kaya Genç digs into Turkey’s censorship of the internet. In the rest of the magazine, writers Emilie Pine, Elif Shafak and Kerry Hudson, and theatre director Nicholas Hytner reflect on past famous Index contributors, Václav Havel, Nadine Gordimer, Samuel Beckett and Arthur Miller. We have an extract of the script of the 1977 film Le Camion by Marguerite Duras which has never appeared in English before, and poems by taboo-breaking poet Dean Atta and the Liverpool Poet Brian Patten. We also have an extract of a story by censored Chinese writer Chen Xiwo about a mother and her daughter and their abusive relationship. Plus Index magazine’s first ever crossword by Herbashe.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Special Report: Border forces: how barriers to free thought got tough”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Big brother at the border by Rachael Jolley

Switch off, we’re landing! by Kaya Genç Be prepared that if you visit Turkey online access is restricted

Culture can “challenge” disinformation by Irene Caselli Migrants trying to cross the Mediterranean to Europe are often seen as statistics, but artists are trying to tell stories to change that

Lines of duty by Laura Silvia Battaglia It’s tough for journalists to visit Yemen, our reporter talks about how she does it

Locking the gates by Jan Fox Writers, artists, academics and musicians are self-censoring as they worry about getting visas to go to the USA

Reaching for the off switch by Meera Selva Internet shutdowns are growing as nations seek to control public access to information

Hiding your true self by Mark Frary LGBT people face particular discrimination at some international borders

They shall not pass by Stephen Woodman Journalists and activists crossing between Mexico and the USA are being systematically targeted, sometimes sent back by officials using people trafficking laws

“UK border policy damages credibility” by Charlotte Bailey Festival directors say the UK border policy is forcing artists to stop visiting

Ten tips for a safe crossing by Ela Stapley Our digital security expert gives advice on how to keep your information secure at borders

Export laws by Ryan Gallagher China is selling on surveillance technology to the rest of the world

At the world’s toughest border by Steven Borowiec South Koreans face prison for keeping in touch with their North Korean family

Stripsearch by Martin Rowson Bees and herbaceous borders

Inside the silent zone by Silvia Nortes Journalists are being stopped from reporting the disputed north African Western Sahara region

The great news wall of China by Karoline Kan China is spinning its version of the Hong Kong protests to control the news

Kenya: who is watching you? by Wana Udobang Kenyan journalist Catherine Gicheru is worried her country knows everything about her

Top ten states closing their doors to ideas by Mark Frary We look at countries which seek to stop ideas circulating[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row disable_element=”yes”][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Global View”][vc_column_text]Small victories do count by Jodie Ginsberg The kind of individual support Index gives people living under oppressive regimes is a vital step towards wider change[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”In Focus”][vc_column_text]Germany’s surveillance fears by Cathrin Schaer Thirty years on from the fall of the Berlin wall and the disbanding of the Stasi, Germans worry about who is watching them

Freestyle portraits by Rachael Jolley Cartoonists Kanika Mishra from India, Pedro X Molina from Nicaragua and China’s Badiucao put threats to free expression into pictures

Tackling news stories that journalists aren’t writing by Alison Flood Crime writers Scott Turow, Val McDermid, Massimo Carlotto and Ahmet Altan talk about how the inspiration for their fiction comes from real life stories

Mosul’s new chapter by Omar Mohammed What do students think about the new books arriving at Mosul library, after Isis destroyed the previous building and collection?

The [REDACTED] crossword by Herbashe The first ever Index crossword based on a theme central to the magazine

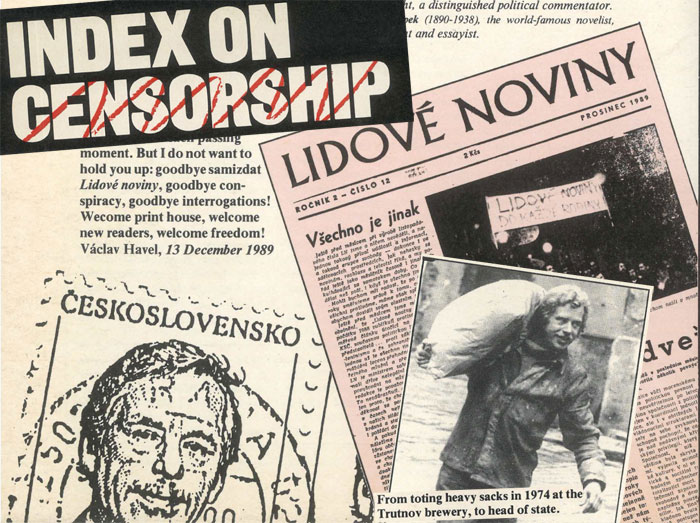

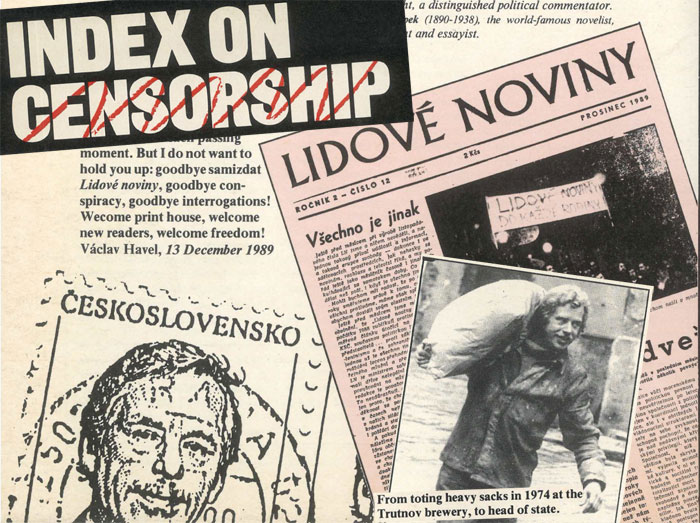

Cries from the last century and lessons for today by Sally Gimson Nadine Gordimer, Václav Havel, Samuel Beckett and Arthur Miller all wrote for Index. We asked modern day writers Elif Shafak, Kerry Hudson and Emilie Pine plus theatre director Nicholas Hytner why the writing is still relevant

In memory of Andrew Graham-Yooll by Rachael Jolley Remembering the former Index editor who risked his life to report from Argentina during the worst years of the dictatorship[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Culture”][vc_column_text]Backed into a corner by love by Chen Xiwo A newly translated story by censored Chinese writer about the abusive relationship between a mother and daughter plus an interview with the author

On the road by Marguerite Duras The first English translation of an extract from the screenplay of the 1977 film Le Camion by one of the greatest French writers of the 20th century

Muting young voices by Brian Patten Two poems, one written exclusively for Index, about how the exam culture in schools can destroy creativity by the Liverpool Poet

Finding poetry in trauma by Dean Atta Male rape is still a taboo subject, but very little is off-limits for this award-winning writer from London who has written an exclusive poem for Index[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Column”][vc_column_text]Index around the world: Tales of the unexpected by Sally Gimson and Lewis Jennings Index has started a new media monitoring project and has been telling folk stories at this summer’s festivals[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Endnote”][vc_column_text]Endnote: Macho politics drive academic closures by Sally Gimson Academics who teach gender studies are losing their jobs and their funding as populist leaders attack “gender ideology”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe”][vc_column_text]In print, online, in your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Read”][vc_column_text]The playwright Arthur Miller wrote an essay for Index in 1978 entitled The Sin of Power. We reproduce it for the first time on our website and theatre director Nicholas Hytner responds to it in the magazine

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Read”][vc_column_text]The playwright Arthur Miller wrote an essay for Index in 1978 entitled The Sin of Power. We reproduce it for the first time on our website and theatre director Nicholas Hytner responds to it in the magazine

READ HERE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]In the Index on Censorship autumn 2019 podcast, we focus on how travel restrictions at borders are limiting the flow of free thought and ideas. Lewis Jennings and Sally Gimson talk to trans woman and activist Peppermint; San Diego photojournalist Ariana Drehsler and Index’s South Korean correspondent Steven Borowiec

LISTEN HERE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

19 Jun 2012 | Middle East and North Africa, Volume 41.02 Summer 2012

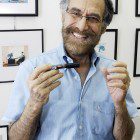

The Syrian regime has gone to great lengths to silence the satirical commentary of Ali Ferzat. But the celebrated cartoonist and Index award winner has no intention of letting the censors keep him down. Malu Halasa reports

The Syrian regime has gone to great lengths to silence the satirical commentary of Ali Ferzat. But the celebrated cartoonist and Index award winner has no intention of letting the censors keep him down. Malu Halasa reports

Three months before the start of the Syrian revolution in March last year, Ali Ferzat broke with his own satirical convention: he stopped using symbolism in his cartoons to criticise the regime and began to target identifiable individuals, including the president himself. He describes the shift as pushing through “the barrier of fear”. The first cartoon in Ferzat’s new series showed President Bashar al Assad agitated at seeing the traditional day of mass demonstrations against the regime, Friday, marked on a wall calendar. Another had him hitching a lift from Gaddafi making his own getaway in a car. The third featured the “chair of power”, one of Ali Ferzat’s iconic symbols, with the springs popping out of the cushion and Bashar hanging onto its arm.

Drawing the president, Ferzat admits, was a personal and political breakthrough — if not foolhardy. “It is quite suicidal to draw someone who is considered a godlike figure for the regime and the Ba’ath party, but still I did it and people respected that courage and started carrying banners with caricatures in the protest to show how they feel about things.”

Drawing the president, Ferzat admits, was a personal and political breakthrough — if not foolhardy. “It is quite suicidal to draw someone who is considered a godlike figure for the regime and the Ba’ath party, but still I did it and people respected that courage and started carrying banners with caricatures in the protest to show how they feel about things.”

Ferzat must have anticipated that his actions might lead to violent repercussions. Last August, pro-regime forces viciously assaulted him and broke both his hands. During the attack, one of the assailants yelled at him, “Bashar’s shoe is better than you.” Article 376 of the Syrian penal code makes it an offence to insult or defame the president, and carries a six-month to three-year prison sentence.

The most lauded cartoonist of the Arab spring, Ferzat has won countless international prizes — including this year’s Index Freedom of Expression Award for the Arts. For more than 40 years, he has been delivering his own scathing messages to dictatorship. Published daily in al Thawra (the Revolution) newspaper in Damascus for a decade, he was a thorn in the side of Hafez al Assad. In the early noughties, the launch of his satirical newspaper al Doumari (the Lamplighter) was considered a hopeful sign in the nascent presidency of Hafez’s heir. Last December, when Bashar al Assad was asked about the attack on Ali Ferzat by the American news commentator Barbara Walters, he responded, “Many people criticise me. Did they kill all of them? Who killed who?’” Such comments made little sense and attest to Ferzat’s power, whether convalescing in a hospital bed or through his drawings.

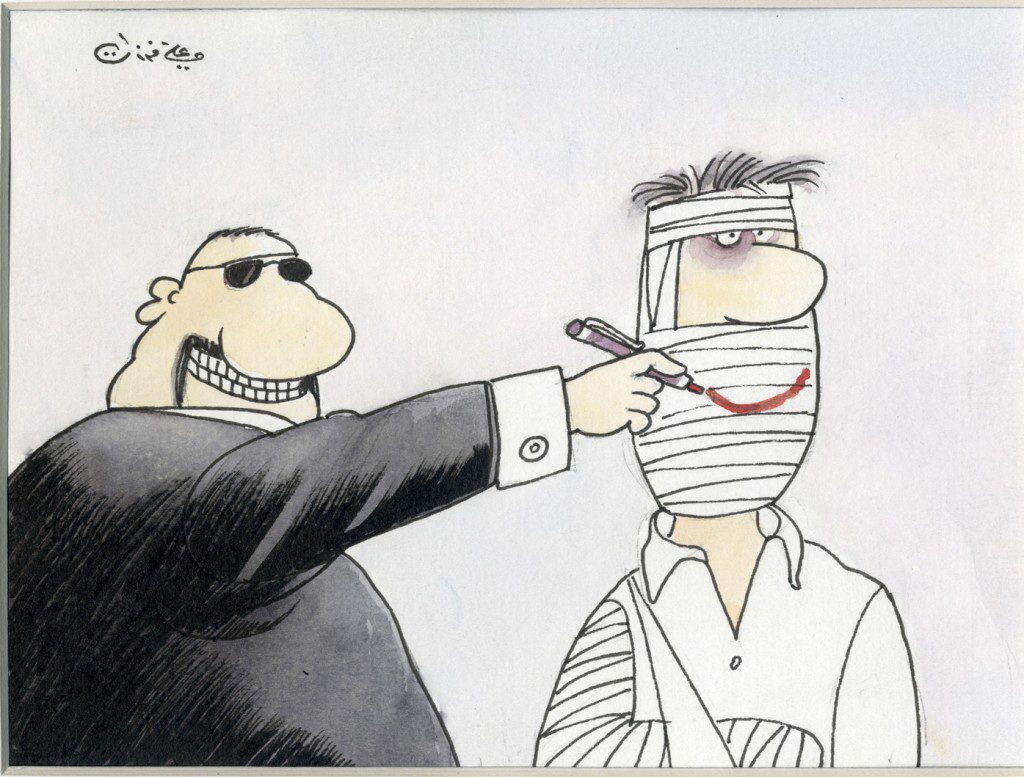

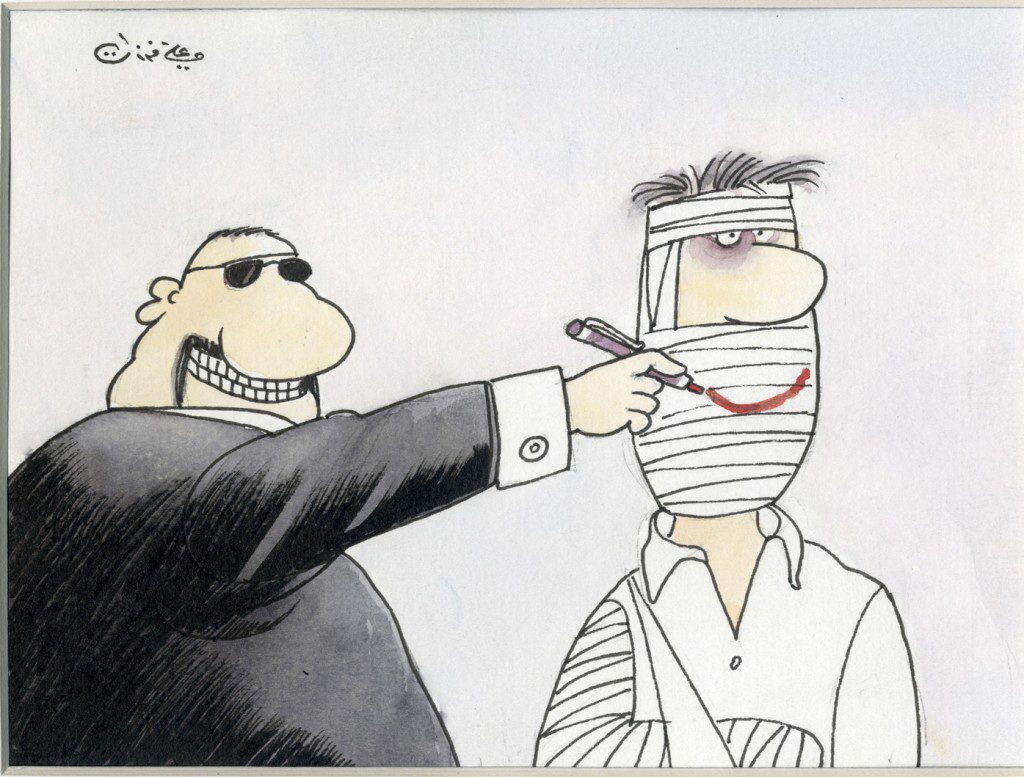

There are two cartoons by Ferzat embedded in my own visual consciousness of Syria during years of visiting and writing about the country. The first is a drawing of a man whose head has been sliced and popped open at the airport. Instead of searching the luggage on the rack, a uniformed authority figure inspects the contents of the man’s brain. The other is of a dismembered prisoner hanging in a cell, body parts everywhere, while the jailer sits on the floor, sharp implements to hand, crying over a television soap opera. Both of them were a comment on the secret life that routinely takes place in Syria, the self-censorship that is sometimes needed to survive and the ongoing activities inside prisons that are rarely officially acknowledged in the state media.

Speaking the truth

In a recent exhibition of Ali Ferzat’s work at the MICA gallery in London, there were numerous examples of his coded messages: the armchair of salat (representing ruling power), the shortened ladder to suggest the gulf between the political elite and the nobodies (sometimes in a hole) or the ever busy authority figure waving a roll of toilet paper like a flag. The messages are inescapably clear but their target is not always what one might expect. In one colourful drawing, a man is trying to pluck fruit from a tree, but the three ladders on which he is standing have been laid horizontally, not vertically. Pausing beneath this picture, Ferzat points out: “Yes, I always speak truth to power. Sometimes it’s not only the president to be blamed but the people too.” The gallery, usually closed at the weekend, was filled with Syrians and their families within minutes of its unscheduled opening. Everyone, from grown men to children of all ages, photographed the cartoons on the walls with their mobile phones.

Ferzat’s unique visual vocabulary, developed in extreme circumstances, has had an unexpected reach:

To survive and get around censorship, my caricatures had to be speechless and rely instead on symbols. That gave them an international aspect I did not intend in the first place. So I managed to get the voice of people inside Syria to the outside, through channels of common human interest.

During his stay in London in the spring, Ferzat received good news. There is an interest in reviving al Doumari, with plans to publish it in exile in Dubai and, ultimately, hopefully back home as well. One gets the impression that no matter where Ferzat is — he currently resides in Kuwait because his family thinks it is too dangerous for him to be in Damascus — living away from the revolution has been frustrating. He spends most nights watching the Arabic news channels and drawing until the early hours. His right hand, which was fractured in the attack last summer, remains a little stiff, although that is not evident in the first two cartoons he drew when he was able to move his fingers. One shows an armoured Trojan warhorse with marauding tanks for hooves. The second is, again, a tank poised on its back wheels, ready to crush a lone green shoot sprouting from the ground.

False springs

The Syrian people are a major influence on his work. “Drawing is first of all a means and not a purpose in itself,” he says.

The artist is always the one who produces an idea, but if that person is not living within his community then how can he reflect what his community is going through? Art is about being with your own people and having a vision of what they need. You can’t sit in your room isolated behind your window and draw about life — it doesn’t work like that.

The revolution was sparked in March 2011 when young graffiti artists in Deraa, between the ages of nine and 15, were arrested and tortured for writing government slogans on the walls. The sale of spray paint is now banned in Syria unless ID papers are shown.

There have been many false springs in the country’s turbulent political history. A decade ago, and just a few months after Bashar al Assad assumed the presidency, Syrian artists and intellectuals were hopeful that change was possible in their country, a sentiment that began in Ferzat’s case when Bashar al Assad, a “tall dude with a large entourage”, walked into his exhibition filled with censored cartoons. (Ferzat always shows banned cartoons in his exhibitions.) When the new president asked Ferzat how he might be able to gauge popular opinion, the cartoonist urged him to simply talk to the people. Eventually Bashar telephoned him and said he was having a Pepsi with ordinary folk in the street. This was during the so-called Damascus spring of the early noughties, when the regime was courting artists and intellectuals. Imbued by optimism in 2001, Ferzat started his satirical newspaper al Doumari, but as the mood of the political elite reverted to tried and trusted methods, so did the fortunes of his weekly. By the time it closed in 2003, 105 issues later, he had survived two assassination attempts that were never investigated. Thirty-two court cases had been filed against the newspaper and advertisers had stopped advertising.

An incredible heritage: satire in the Middle East

Historically, cartoonists have been astute in their circumvention of censorship. As Fatma Müge Göçek has shown, under the Ottoman press laws of the early 1900s, they sent erasable drawings to the censors and, after approval, substituted other images in their place. Newspapers at that time also appeared with black boxes where a cartoon had been censored. As the gap widened between official pronouncements and reality – or as Václav Havel once said, ‘People know they are living a lie’ – caricatures became an important means of expression in the Middle East. Now cyberspace provides a comparatively safe haven for pictures and ideas that cannot be expressed in print.

Editorial cartooning, like journalism, is considered a western invention, but the convention of satire in the Middle East is as old as the stories of Alf Laila wa Laila (A Thousand and One Nights). Ferzat’s peers include the Egyptian Baghat Othman, who parodied Sadat, Palestinian Naji al Ali, creator of the Palestinian barefoot boy Hanzala (with his back always to the reader in rejection of the world around him) and Algerian Chawki Amari, now in exile in Paris after serving a three-year sentence in his country for drawing the country’s flags in a cartoon that was seen as ‘defacing’ a national symbol. The Syrians also bring something new to the mix, which springs from a sense of humour coloured by the experience of dictatorship, coupled with sexual innuendo. This blend is nicely demonstrated by a joke from the 1980s that is still pertinent, as recently told to me by a political activist.

A guy used to talk about the president. The mukhabarat, secret police, picked him up and started beating and torturing him. They told him, ‘Stop making jokes about the president. Stop talking about the president. You can tackle whatever issues you want, but in the end you always have to say: this has nothing to do with the president. The president is not aware of this.’ So the minute the guy is released, he sees his family waiting by the door and says, ‘Have you heard, the wife of the president is pregnant and the president has nothing to do with it. He’s not even aware of it.’

Even in his comic strips for juveniles, Ferzat has challenged traditional sensibilities in Syria, a country known for channelling propaganda through state-sponsored children’s publications. Ferzat was 26 years old when he created ‘The Travels of Ibn Battuta” for the popular Usama magazine, published in 1977. In the strip, the famous medieval Arab traveller Ibn Battuta is depicted with a moustache and beard, wearing a turban in the shape of the globe. Ferzat demystifies Ibn Battuta by drawing Muhammad Ali, Omar Sharif and the pop singer Abdel Halim Hafiz, with a turban globe on their heads; as avatars of Ibn Battuta, they respectively box, hug a leading lady and sing. Later in the strip, as the historic traveller pulls his donkey into the present day, his size shrinks, suggesting he is overwhelmed by modern life.

A letter sent to the editor of Usama complained about this portrayal of Ibn Battuta. Ferzat did not use one of the traditional Arab figures of ridicule such as the poet Abu Nuwas or the folk character Juha as his fumbling protagonist, but instead a notable historical personage, which the letter writer found highly insulting. This was at a time when the magazine was already starting to change, and was publishing less controversial material, as Allen Douglas and Fedwa Malti-Douglas show in their study of Arabic comic strips.

Self censorship, survival and living without boundaries

Originally from a Sunni Muslim family in Homs, Ferzat describes freedom of the press as “a responsibility”. He stresses:

It’s not as if I should do whatever I feel like doing, regardless of the consequences. It is a matter of moral commitment at the end of the day and varies between countries, depending on the culture and civil liberties. You have to find the right balance. Some newspapers have no obligation, not even morally, and they refrain from nothing and then call it ‘freedom’. Meanwhile other newspapers censor human interest stories. I see both as bad — whether too much suppression in the name of commitment, or too much unethical commitment in the name of freedom. They are both the same.

During prolonged periods of dictatorship, there have been unexpected chinks in the wall of silence, which Lisa Weeden outlines in her tour de force Ambiguities of Domination. One way ordinary Syrians thwarted the cult of Hafez al Assad that pervaded their daily lives was in their choice of newspapers. Throughout the 1970s, al Thawra published a daily editorial cartoon by Ferzat. When he was dropped from the newspaper, al Thawra experienced a 35 per cent drop in sales and was forced to ask the cartoonist to return. Ferzat’s stories about his days there are particularly amusing and they reveal just how much leeway can exist in what at first glance appears to be a monolithic system. In some instances, the offending cartoon would be published in the paper. Then the abusive phone calls from the minister of information would begin.

Ferzat continues:

They came with this new procedure. First the editor-in-chief had to look at the caricature. If he approved it, he had to send it to the general manager. If he approved it, or if he found it controversial and difficult to understand, he had to send it to the minister of information. Take into consideration that the minister of information was a bit of an ass, he would say ‘Yes’ because he didn’t understand it and the next day the people would get the meaning because it only took commonsense. Suddenly the angry phone calls would start all over again.

According to Italian visual critic Donatella Della Ratta, Bashar al Assad’s Syria is ruled by what she calls “a whispering campaign” waged by competing elites, the secret police, the official media and finally the president and his inner circle. All of the different factions are involved in censorship: it takes many pillars of society to control the flow of information and ideas in a totalitarian state.

In such a society, what is the difference between self-censorship and survival for someone like Ferzat? “What I can tell you is that I have no boundaries,” he says.

I don’t have a censor or a policeman in my head before I draw. However, it is not requested of fedayeen — freedom fighters — to be suicidal. As an artist, I’m not going to go and find a landmine and sit on top of it. I invented the symbols that actually manipulate the censor and survive the dangers of punishment. I put simple codes and symbols in my drawings, and anyone who has the capacity to notice things would understand them. That is what I do to secure myself and not be suicidal.

He concludes: “At the end of the day, my drawings and caricatures are part of the daily culture of the street. I want to represent the consciousness of the street, of the people, and I do, and that gives my work value.”

As Ferzat and the graffiti artists of Deraa, who sparked a revolution over a year ago, have shown: Sharpie pens and spray paint can be the most effective tools against a brutal regime.

Malu Halasa is a writer and editor. Her books include The Secret Life of Syrian Lingerie (Chronicle Books)

This article appears in the new edition of Index on Censorship. Click on The Sports Issue for subscription options and more

22 Dec 2011 | Magazine

This piece by Vaclav Havel was published in Index on Censorship in 1984 after he was released from prison in March 1983, having served almost four years on charges of “subversive activities against the Socialist state” of Czechoslovakia. The “subversive activities” were his signature on the Charter 77 manifesto (he was one of the three original spokesmen of Charter 77), his membership of the Committee for the Defence of the Unjustly Prosecuted (VONS) and his numerous plays and essays which, in his own country, appear only in samizdat editions. Our previous issue, Index 6/1983, contained the first interview given by Havel to a foreign journalist after his release from imprisonment.

Havel died on 17 December this year.

The following sketch is Havel’s first literary work written since leaving prison. Its world premiere took place at the end of November 1983 in Stockholm and is published here by permission of Rowohlt Theater-Verlag, Reinbek. The Stockholm performance was introduced by Vaclav Havel himself, the tape-recorded message he sent from Prague being played to the audience. The message appears on page 15.

Dramatis personae:

XIBOY

KING (a trustie)

FIRST PRISONER

SECOND PRISONER

THIRD PRISONER

(As the curtain rises, we see a door, left, with the FIRST, SECOND, and THIRD PRISONER crowding the doorway, KING in front. All four have shaven heads and a variety of tattoos on their arms and torsos — KING most of all. They are dressed in prison uniforms and are gazing intently at XIBOY. On the opposite side of the stage there is a tier of three iron bunks; XIBOY is sitting on the top one, like the others in prison garb and with shaven head but no tattoos. XIBOY is a newcomer and he looks with some apprehension at the group in the doorway. A long, tense silence…)

KING (to XIBOY) I hear you lit a fag after slop – out…

(Short pause)

FIRST PRISONER (to KING) ‘e did — I saw ‘im.

KING (to SECOND PRISONER) That right?

SECOND PRISONER Sure, that’s right.

KING (to XIBOY,) Don’t you know when we fall out for breakfast?

(Short pause)

FIRST PRISONER (to KING) Sure, he knows…The minutes after slop-out.

KING (to SECOND PRISONER.) Does ‘e know?

SECOND PRISONER Sure he knows! They tell all the new boys, don’t they…

KING (to XIBOY) Now listen ‘ere, friend. We have ten minutes between slop-out and breakfast. In that time we’ve all gotta get dressed, those as wants can wash or ‘ave a piss, there’s no objection to that, you understand, everyone’s got a perfect right to do it, if they wanna, you can even start making your bed so we don’t all start at once and get in each other’s way. And we open the windows to get rid of all the farts first thing. That’s the custom ‘ere, that’s the way it’s done and always ‘as been. Then we all grab our caps and food bowls and wait for the order to fall in. And when they yell fall in’ we gotta look sharp and line up outside the cell. If we don’t get out there quick enough, they send us back and we gotta wait our turn again. So we don’t want anybody fartarsing around holding things up, looking for his things or tipping a fagend or anything like that — and the rest of us get in the shit on ‘is account. Understand? Because of one lousy slowcoach we ain’t all gonna go back and ‘ang around waiting. I ‘ope that’s clear. And if anyone thinks it ain’t, we’ll soon put ‘im right!

FIRST PRISONER (to KING) It’s clear, all right, and everyone does it just like you said.

SECOND PRISONER (to XIBOY) That’s right — and if some cunt thinks ‘e can mess us about, ‘e’ll do it just once and never again . ..

KING(to XIBOY) So, as I said, there’s a hell of a lot to do between slop-out and breakfast. No time for fartarsing around. Much less for smoking. That’s not the way we do things ‘ere. Now, after breakfast, that’s something else again, then you can light up if you’ve got any fags, that is. Then there’s time and nobody gives a shit. But not before breakfast. That’s how it’s always been in this pad, and it’s going to stay that way. Nobody’s gonna tell me they can’t wait a lousy twenty minutes for a smoke. That ain’t asking too much, is it? (to SECOND PRISONER) Am I right?

SECOND PRISONER Sure you are.

FIRST PRISONER (to KING) We can wait.

KING (to XIBOX) So, from now on remember — no smoking before breakfast…

FIRST PRISONER Especially as we’re trying to air the fucking place…

KING (to XIBOY) Yeah, that’s right. And some people just can’t stand the smell of smoke first thing in the morning. They don’t like it, their lungs don’t like it, they can’t stand it. As is their right. Is that clear?

(XIBOY says nothing, looks embarrassed and shrugs)

SECOND PRISONER (shouts at XIBOY) Didn’t you hear what ‘e said? (XIBOY says nothing, looks embarrassed, shrugs) Anyone we catch smoking after slopout gets a fistful, see?

KING (to XIBOY) What they do in other cells, that’s their business. But nobody smokes in this one after slop-out. That goes for everybody, ‘specially for new boys like you. That’s all I wanted to say to you, friend. And not just for myself but for all of us. (to SECOND PRISONER) Right?

SECOND PRISONER Right.

FIRST PRISONER (to KING) That’s what we all say — right…

KING (to XIBOY; Everybody saw you smoking first thing, and everybody yakked about it. But I told ’em: ‘e’s a new boy, doesn’t know the ropes yet. And so they stopped yakking. So you’re OK for today. But next time just remember we don’t hold with nobody trying to be clever and going it alone. Not on your life . ..

FIRST PRISONER (to KING) As long as I been ‘ere, nobody ever had the nerve to light a fag before breakfast.

KING (to XIBOY) So, as I said, you got away with it this time, but see it don’t ‘appen no more. Is that clear?

(XIBOY looks embarrassed and shrugs)

SECOND PRISONER (yells at XIBOY) What’re you gawping at, you cunt? King asked you a question!

(Silence)

KING (to XIBOY) We’re trying to be nice to you, see? So we’ll skip it this once—but now you know and kindly keep your nose clean.

(Longer silence)

Oh, and while we’re on the subject … From tomorrow, you’ll make your bed exactly like all the rest of us. If the others can do it, so can you. We don’t want to lose a point every day just because some stupid bastard doesn’t know how to make his bed properly, do we? We don’t want the whole lot of us to get it in the neck on account of one miserable rookie what doesn’t know how to make his bed. So you’d better hurry up and learn, ‘cos if tomorrow your bed isn’t just like everybody else’s, we’ll make you practise all evening.

SECOND PRISONER (to XIBOY,) We’ll make you do it ten times in a row, see if we don’t.

KING (to XIBOY,) Blanket’s gotta be two inches from the edge on both sides, the sheet neatly folded over, and so on and so forth. The boys’ll show you how it’s done.

FIRST PRISONER (to KING,) I’ll show ‘im . . .

KING (to XIBOY,) Is that clear?

(Silence)

Everybody in ‘ere gets the ‘ang of it sooner or later, so no reason why you shouldn’t get the ‘ang of it. Understand?

(Silence)

SECOND PRISONER (to XIBOY,) Bloody hell! Cat got your tongue, you bastard? Speak up when King asks you something!

FIRST PRISONER (to KING,) What ‘s the matter with ‘im? Stupid idiot!

KING (to XIBOY) Did you clean the washbasin?

(Silence)

Your turn to scrub and clean this week, so you’d better look smart! And if you think you’re just going to tickle the floor with the brush and that’s it, you’re bloody well mistaken. You get down and scrub the floor under the bunks, ‘specially in the corners by the wall —the screws shine their torches down there. You dust everywhere, and the washbasin’s gotta be washed, wiped dry and shined — and the same goes for the kaazie. Today it’s a mess, so you can thank your lucky stars we haven’t had the screws round ‘ere. They’d ‘ave shown you a thing or two. Tonight, before inspection, I’ll come and look personal like. We’re all in the same boat ‘ere, nobody gets any privileges, ‘specially not a rookie whose fag-end is still burning outside the prison gate! Pankrac Prison, Prague

SECOND PRISONER (yells at XIBOY) So why don’t you come down off of there, you cunt, when King’s talking to you!

(XIBOY remains sitting on his bunk, smiling in embarrassment. Tense silence, SECOND PRISONER is about to lunge at XIBOY and drag him down but KING stops him)

KING (to SECOND PRISONER,) Wait a sec!

(Silence)

(to XIBOY) Now look ‘ere, me lad! If you’ve got it in yer ‘ead that you’re going to do as you bloody well please ‘ere, or maybe play at being King, you’ve got another think coming! We know how to deal with the likes of you. Understand?

(Silence)

FIRST PRISONER (to KING) What a stubborn bastard!

SECOND PRISONER (to XIBOY,) Come down off that bloody bunk, and be quick about it!

(Silence — XIBOY doesn’t move)

SECOND PRISONER (to XIBOY,) Well…?!

(Silence — XIBOY doesn’t move)

KING (to XIBOY,) Now then, you, I don’t take kindly to them as tries to make a monkey out of me. So don’t get any ideas!

FIRST PRISONER (to XIBOY,) Down you come this minute and apologise to King!

(Silence — XIBOY doesn’t move, just sits there smiling in embarrassment)

SECOND PRISONER (yells at XIBOY.) You fucking mother-fucker!’

(SECOND PRISONER leaps forward and catches XIBOY by one leg, pulling him down, XIBOY falls on the floor, SECOND PRISONER kicks him and returns to KING’S side, XIBOY rises slowly, looks at the others, puzzled. Silence.)

THIRD PRISONER (softly) ‘ere, lads…

(Silence — they all gaze at XIBOY)

KING (without turning to THIRD PRISONER,) What?

(Silence — they all gaze at XIBOY)

THIRD PRISONER (softly) Know what? He’s some kind of a bloody foreigner…

(All three look questioningly at KING. Tense silence)

KING (after a pause, softly) Well, that’s his bloody funeral…

KING starts out menacingly towards XIBOY, followed by FIRST, SECOND and THIRD PRISONER. They slowly edge closer to him. Curtain falls)

(CURTAIN)

Translated by George Theiner. This play originally appeared in Index on Censorship magazine in 1984 Volume 13: Issue 13

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Read”][vc_column_text]The playwright Arthur Miller wrote an essay for Index in 1978 entitled The Sin of Power. We reproduce it for the first time on our website and theatre director Nicholas Hytner responds to it in the magazine

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Read”][vc_column_text]The playwright Arthur Miller wrote an essay for Index in 1978 entitled The Sin of Power. We reproduce it for the first time on our website and theatre director Nicholas Hytner responds to it in the magazine