31 Jul 2019 | Journalism Toolbox Spanish, Kenya

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”107800″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_custom_heading text=”El periodista keniano Yassin Juma permanece oculto desde su arresto por informar sobre los atentados de Al-Shabab. En su primera conversación telefónica desde que pasara a la clandestinidad, Juma habla con Ismail Einashe sobre el aumento de las amenazas que sufren los periodistas en Kenia.”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

La noche del 23 de enero de este año, un sábado, el periodista Yassin Juma estaba enfermo en casa, acostado. Salió de su hogar en Donholm, un distrito de Nairobi, para comprar medicinas en la farmacia de su barrio de la capital keniana. Desde allí se acercó dando un paseo a su carnicería local. Al poco rato de llegar al comercio fue detenido por cuatro hombres del departamento de investigación criminal (CID), una unidad de la policía keniana.

Los hombres escoltaron a Juma a su casa, donde se encontró a 14 personas del CID registrándola de arriba a abajo delante de su esposa e hijos. “Buscaban aparatos electrónicos, ordenadores portátiles”, explica a Index. Juma es un veterano periodista de investigación, conocido por sus noticias sobre la guerra contra Al-Shabab, el grupo militante islamista con base en Somalia.

Su arresto vino a raíz de haber publicado en sus redes sociales las últimas noticias sobre un atentado de Al-Shabab contra las Fuerzas Armadas de Kenia (KDF) en El Adde, Somalia. El 18 de enero hizo públicas las muertes de 103 soldados de las KDF en el lugar tres días antes en un ataque de los militantes. Juma, que llevaba años informando sobre el conflicto, afirma que cuenta con una fuente fiable dentro de las KDF que confirmaba la noticia.

Pero sus publicaciones se contradecían con las declaraciones oficiales de las KDF. Unos días antes, Joseph Nkaissery, secretario del gabinete de interior y general retirado, había advertido públicamente que se arrestaría por simpatizar con Al-Shabab a todo aquel que hiciera circular información sobre los soldados de las KDF muertos en los atentados de El Adde.

Bajo la presidencia de Uhuru Kenyatta, hijo del primer presidente de Kenia, el estado ha estado apoyándose en la ley para incriminar y silenciar a periodistas. Henry Maina, director de las secciones de África oriental y el Cuerno de África de la ONG Article 19, especializada en libertad de expresión, dice: “Había muchas leyes en los códigos pero apenas se utilizaban para incriminar a los periodistas”. El artículo 29 de la Ley de Información y Comunicación criminaliza el “uso indebido de un sistema autorizado de comunicación”, refiriéndose a la publicación en internet de información que las autoridades consideren ilegal.

El 19 de enero arrestaron al bloguero Eddy Reuban Ilah, acusado, según dicha ley, de compartir en un grupo de WhatsApp imágenes de soldados de las KDF muertos en El Adde. Juma se enfrentó a cargos similares por el “uso indebido de un aparato de telecomunicaciones”. Había compartido una entrada de Facebook del hermano de un soldado de las KDF, de origen keniano-somalí, muerto en el atentado. Lo acusaban de haber compartido dicha entrada con sus seguidores sin el permiso de las KDF. Juma cree que tácticas como esta son un “método clásico para silenciar a los periodistas”.

Para los periodistas kenianos, los nuevos medios de difusión se han convertido en una herramienta clave de su arsenal informativo. Juma, por ejemplo, tiene 19.000 seguidores, y utiliza las redes sociales para sortear los medios tradicionales y conectar directamente con su público. Explica que, durante los atentados en El Adde, “la gente estaba ansiosa por enterarse de lo que estaba pasando” y, sin embargo, los medios de comunicación generalistas no estaban cubriendo el incidente. “Las redes sociales me dieron la oportunidad de ofrecer información a las familias y al público en general”, explica a Index.

El gobierno keniano ha negado querer intimidar o silenciar a los periodistas. Nkaissery, secretario del interior, declaró a la web de actualidad African Arguments que el gobierno respeta a los medios independientes y la libertad de expresión, si bien añadió que esta “libertad ha de disfrutarse de forma responsable”.

Kenia gozaba de la reputación de ser uno de los entornos más libres para el periodismo en África oriental, pero esa percepción está cambiando rápidamente. Este año, el gobierno de Kenyatta ha tomado medidas brutales contra las libertades de prensa.

Según el Observatorio de los Derechos Humanos, los esfuerzos del país por combatir las amenazas a su seguridad tras varios graves atentados terroristas de Al-Shabab se han visto “oscurecidos por ciertas tendencias en curso de graves violaciones de derechos humanos por parte de las fuerzas kenianas de seguridad, como ejecuciones extrajudiciales, detenciones arbitrarias o torturas”. La Comisión Nacional de Derechos Humanos de Kenia afirma haber registrado 81 “desapariciones forzadas” desde 2013.

Maina asegura que Article 19 ha visto un aumento acusado de los riesgos y ataques sufridos por los periodistas en Kenia. Entre enero y septiembre de 2015, Article 19 registró 65 casos de reporteros y usuarios de redes sociales víctimas de agresiones en 42 incidentes distintos, casos de violencia física incluida, además de amenazas por teléfono y SMS, citaciones de la policía y restricciones legales. De todos esos incidentes, 22 casos estaban vinculados a periodistas que cubrían historias de corrupción, 12 de protestas y ocho de terrorismo y crímenes. Maina añade que solo en tres de los 42 casos se ha realizado una investigación y llevado a los responsables a los tribunales. En total suman el 7%, cosa que Maina considera “un nivel inaceptable de impunidad en lo que a ataques contra periodistas se refiere”.

Maina reconoce que la censura internacional a la que ha estado sometida la ley ya ha contribuido a mejorar la situación, y que el Tribunal Supremo keniano decidió hace poco que el artículo 29 de su ley de información y comunicación era inconstitucional. “Algunos blogueros y comunicadores de redes sociales que se enfrentaban a cargos según el artículo impugnado han visto cómo estos se retiraban, y han sido absueltos en los casos en los que no había más pruebas que permitieran acciones judiciales para acusarlos de otros delitos.

“Dado nuestro sistema legal, todos los casos similares se cerrarán en el próximo juicio programado. No se han registrado más situaciones de blogueros y reporteros acusados bajo el artículo 29 de la ley”.

De su casa, Juma fue conducido a la comisaría de Muthaiga, donde lo interrogaron sobre su trabajo periodístico. Explica: “Tenían mi teléfono; querían saber quiénes eran mis contactos en Somalia”. Lo retuvieron durante dos días, tras lo cual un agente entró en su celda y anunció: “Ha habido un cambio de planes”. Lo liberaron sin cargos poco después.

Juma volvió a casa, pero, al cabo de un tiempo, temiendo más repercusiones, decidió huir y esconderse con su familia. “Esta es la primera llamada que hago. Vivimos en la clandestinidad”, cuenta. Juma está acostumbrado a que lo amenacen por su trabajo periodístico, pero lo que ha cambiado en los últimos años, dice, es lo graves que se han vuelto las amenazas.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Ismail Einashe es un periodista independiente afincado en Londres. Tuitea desde @IsmailEinshe

Traducción de Arrate Hidalgo Sánchez[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

31 Jul 2019 | Journalism Toolbox Russian, Kenya

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Кенийский журналист Ясин Джума продолжает скрываться после своего ареста за репортажи о нападениях «Аш-Шабааб». В своем первом телефонном звонке с тех пор, как он ушел в подполье, Джума беседует с Исмаилом Эйнаше о возрастании количества угроз журналистам в Кении”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”107800″ img_size=”full”][vc_column_text]

Вечером субботы 23 января этого года журналист Ясин Джума лежал дома больной в постели. Он вышел из своего дома (район Донхольм, Найроби, столица Кении), чтобы купить лекарства в местной аптеке. Оттуда он совершил короткую прогулку к местным мясникам. Но вскоре после прихода в магазин его остановили четыре сотрудника отдела уголовного розыска (ОУР), подразделения кенийской полиции.

Джума был доставлен в сопровождении охраны обратно домой, где обнаружил 14 человек из ОУР, обыскивающих его жилище на глазах у жены и детей. «Они искали электронное оборудование, ноутбуки», – рассказал Джума «Индексу». Джума – опытный журналист-расследователь, известный своими репортажами о борьбе против «Аш-Шабааб», базирующейся в Сомали исламистской группы боевиков.

Его арестовали за публикацию в своих аккаунтах социальных сетей новостей о нападении «Аш-Шабааб» на Кенийские силы обороны (КСО) в Эль-Адде в Сомали. 18 января он сообщил, что 103 солдата КСО были убиты там тремя днями ранее в результате нападения со стороны боевиков. Джума освещал этот продолжающийся конфликт в течение многих лет и рассказал, что у него есть надежный источник в КСО, подтверждающий эту историю.

Но его сообщения противоречили официальным заявлениям КСО. Несколько днями ранее министр внутренних дел и отставной генерал Джозеф Нкайссери публично предупредил, что каждый, кто будет распространять информацию о солдатах КСО, убитых во время нападений в Эль-Адде, будет арестован за симпатии к «Аш-Шабааб».

При президенте Ухуру Кениате, сыне первого президента Кении, возглавляемое им государство использует законы для того, чтобы обвинять журналистов и заставить их замолчать. Генри Майна, директор по вопросам свободы слова в Восточной Африке и на полуострове Сомали неправительственной организации «Статья 19», заявил: «Многие законы были внесены в действующее законодательство, но редко использовались для обвинения журналистов». Статья 29 «Закона об информации и коммуникации» предусматривает уголовную ответственность за «ненадлежащее использование лицензионной системы связи», что, по мнению властей, означает публикацию информации в интернете, которая считается незаконной.

19 января блогер Эдди Рубен Илах был арестован по этому закону и обвинен в том, что он распространил в группе мессенджера WhatsApp фотографии убитых в Эль-Адде солдат КСО. Джума столкнулся с аналогичным обвинением за «незаконное использование телекоммуникационного устройства»: он поделился постом в Facebook брата убитого

в Эль-Адде кенийско-сомалийского солдата КСО. Обвинение заключалось в том, что он поделился этим постом со своими подписчиками без разрешения КСО. Джума считает, что такая тактика – «классический способ заставить журналистов молчать».

Для кенийских журналистов новые медиа стали ключевым инструментом в их репортерском арсенале. У Джумы, например, 19 000 Facebook-подписчиков и он использует социальные сети, чтобы обойти традиционные СМИ и напрямую связаться со своей аудиторией. Во время нападений в Эль-Адде он заявил, что «общественность очень хотела узнать, что происходит», однако центральные СМИ не освещали этот инцидент. «Социальные сети дали мне возможность предоставлять информацию общественности и семьям солдат», – рассказал он «Индексу».

Правительство Кении отрицает, что пытается запугать или заставить журналистов замолчать. Министр внутренних дел Нкайссери сообщил сайту текущих событий African Arguments, что правительство уважает независимые СМИ и свободу слова, добавив при этом, что

«такой свободой следует пользоваться ответственно».

У Кении была репутация государства в Восточной Африке с большей свободой для СМИ, но сегодня эта точка зрения меняется. В этом году правительство Кениаты жестоко расправилось со свободой прессы.

Согласно «Хьюман Райтс Вотч», после нескольких крупных террористических атак со стороны «Аш-Шабааб» усилия Кении в борьбе с угрозой государственной безопасности были «омрачены продолжающимися случаями серьезных нарушений прав человека со стороны КСО, включая внесудебные казни, произвольные задержания и пытки». Кенийская национальная комиссия по правам человека заявляет, что с 2013 года зафиксировано 81 «насильственное исчезновение».

Майна рассказал, что «Статья 19» наблюдает резкое увеличение количества рисков и нападений на журналистов в Кении. В период с января по сентябрь 2015 года «Статья 19» зарегистрировала 65 нападений на отдельных журналистов и пользователей социальных сетей – среди них 42 случая, включающие акты

физического насилия, а также угрозы по телефону и в виде текстовых сообщений, вызовы в полицию и правовые ограничения. Из этих инцидентов 22 случая касались журналистов, освещающих коррупцию, 12 – протесты и восемь – терроризм и преступления. Майна добавляет, что только три случая из 42 дел были расследованы, а виновные преданы суду. Эти 7%, по его словам, отображают «неприемлемо высокий уровень безнаказанности в отношении нападений на журналистов».

Майна признает, что международная критика этого закона уже привела к улучшению ситуации, и что Высокий суд Кении недавно постановил, что статья 29 «Закона об информации и коммуникации» является неконституционной. «Некоторым блогерам и активным пользователям социальных сетей, которым предъявили обвинения в рамках оспариваемой статьи, обвинения были сняты при отсутствии других доказательств, позволяющих стороне обвинения инкриминировать им совершение других преступлений, в отношении которых они были оправданы».

«Учитывая нашу правовую систему, все подобные случаи будут сняты с рассмотрения тогда, когда они будут запланированы для слушания в следующий раз. Новых дел о блогерах и журналистах, обвиняемых по статье 29 «Закона об информации и коммуникации», зарегистрировано не было», – отметил он.

Из своего дома Джума был доставлен в полицейский участок Мутайги, где его допросили касательно сообщений в социальных сетях. Он рассказал: «У них был мой телефон, они хотели узнать о моих связях в Сомали». Журналиста продержали два дня, затем офицер вошел в его камеру и объявил: «Планы изменились». Вскоре после этого, его выпустили без предъявления обвинения.

Джума вернулся домой, но, опасаясь дальнейших преследований, позже скрылся со своей семьей. «Это мой первый звонок, мы ушли в подполье», – сообщил он «Индексу». Джума привык получать угрозы за свои репортажи, но, по его словам, в последние годы угрозы стали более серьезными.

Исмаил Эйнаш – журналист-фрилансер из Лондона. Он пишет в Твиттере на аккаунте @IsmailEinshe

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

8 Jul 2016 | Magazine, mobile, Volume 45.02 Summer 2016 Extras

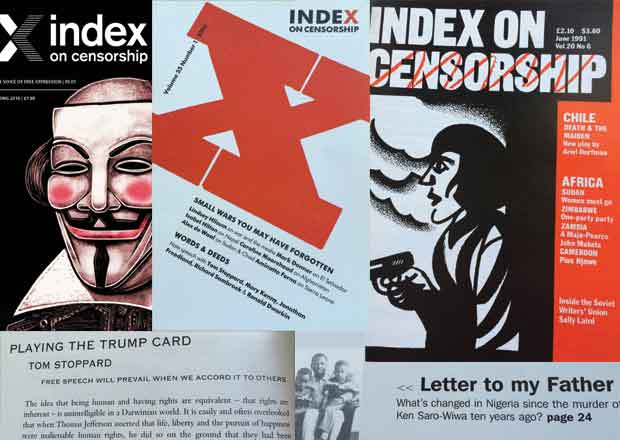

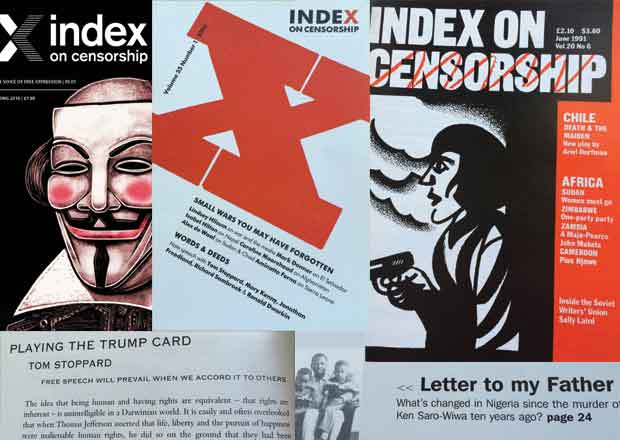

Index writers pick their favourite features from 250 issues

To celebrate the 250th issue of Index on Censorship magazine, we asked some of our contributors to nominate memorable articles from the publication’s long history. Here they share their memories and recommendations.

David Aaronovitch – author, Times columnist and chair of Index on Censorship

We are all familiar with the idea of luvvies. The word suggests the artist, actor or musician who, unread and emoting, trespasses onto the stage of public affairs and gets on everyone’s tits. It is sometimes true but usually wrong. One of my favourite Index magazine pieces (and there are so many to choose from) was written in 2006 by that epitome of the engaged intellectual, Tom Stoppard. Stoppard was involved with Index in its early days and has remained a patron and in this piece, he asks whether freedom of speech really is a human right. This is an awkward question in the middle of a magazine which would want to assist at every turn that a right is exactly what it is – none greater. But Stoppard argues that what makes a society one in which he would want to live is not the demanding of a right, but the according of it – the day-by-day renewed assumption that others will say what they want. Because that’s the way we choose to live.

Playing the Trump Card by Tom Stoppard was published in February 2006 (volume 35, no 1)

Ariel Dorfman – author and playwright

As I am trying to finish a major piece of writing, I didn’t have the time to go to the office where most of my Index back issues await me. I remember stories and poems from countries that generally receive little or no attention and wanted to highlight one of those. Index has published so many of my own works over the decades (I especially think Trademark Territory or Je Suis José Carrasco piece are relevant today), but, hands down, I would have to choose the publication of [my 1990 play] Death and the Maiden as my most important memory. Index was the first to publish the text before it became famous. This is typical of Index’s commitment to those who are on the margins of public notoriety, its mission to bring out of the darkness the voices that are suppressed by tyrants or by neglect and indifference, the voices of the Paulinas of the world.

Death and the Maiden was published in June 1991 (volume 20, no 6)

Ismail Einashe – journalist

I would have to pick Fabrizio Gatti’s piece Undercover Immigrant, which is a stunning piece of journalism. Gatti spent fours years undercover, investigating migrant journeys from Africa to Europe. What is remarkable about his piece, an extract of his book published for the first time in English by Index, is that he so successfully managed to hide his true identity as a Italian by assuming the identity of Bilal, a Kurdish asylum seeker. By doing this, Gatti got unique access into the Lampedusa’s migrant centres, the tiny island in the Med that has become a symbol of Europe’s migrant crisis. Through telling the story of “Bilal”, he was able to get fascinating perspective on the migrant journeys and reveals the shocking stark reality of being a migrant in Italy, a situation which 10 years on from Gatti’s undercover reports has sadly barely changed. Like then, thousands of migrants still die in dinghies trying to reach Europe.

Undercover Immigrant was published in Spring 2015 (volume 44 , issue 1), within a special report on refugee voices. You can also listen to an extract of the piece via an Index podcast

Janet Suzman – actress and director

I am without hesitation going to choose the whole of your Shakespeare-themed spring 2016 edition. I’m choosing it because from the beginning of my career I fervently believed that there was more to Shakespeare – indeed more to all drama – than simply getting one’s teeth into a juicy part. From every corner of the unfree world, the essays you have printed bear me out; theatre is a danger to ignorance and autocracy and Shakespeare still holds the sway. To quote my favourite aperçu: Shakespeare’s plays, like iron filings to a magnet, seem to attract any crisis that is in the air. I congratulate you and Index on giving such space to a writer who is still bannable after 400-plus years.

Staging Shakespeare Dissent was a special report published in spring 2016 (volume 45, issue 1), with an introduction by Index on Censorship magazine editor Rachael Jolley on how Shakespeare’s plays plays have been used to circumvent censorship and tackle difficult issues around the world

Christie Watson – novelist

There are too many articles to choose from, but I chose Ken Wiwa’s Letter to my Father, as it perfectly demonstrates Index on Censorship’s commitment to story-telling. Ken Wiwa’s letter [to his father and environmental activist Ken Saro-Wiwa who was hanged during Nigeria’s military dictatorship] reminds the reader that behind significant political events are personal stories, like the relationship between a son and his father. Index recognises the power of personal stories in order to reach the widest audience.

Ken Wiwa’s Letter to my Father was published in the spring 2005 issue (volume 34, issue 4) on the 10th anniversary of Ken Saro Wiwa’s death in 2005. Ken Wiwa also wrote a letter for the 20th anniversary (summer 2015, volume 44, issue 2). See our Ken Saro Wiwa reading list

Index will celebrate 250 issues of the magazine next week at a special event at MagCulture. To explore over 40 years of archives, subscribe today via Sage Publications. Or sign up for Exact Editions’ digital version, which offers access to 38 back issues.

30 Jun 2016 | Africa, Kenya, Magazine, mobile, Volume 45.02 Summer 2016 Extras

“Yassin Juma is an extraordinary journalist, who has taken great personal risks to get the story of what is happening in the war that is being waged in Somalia against Al-Shabaab,” writer Ismail Einashe told Index on Censorship.

But Juma is now in hiding.

Einashe interviewed the Kenyan investigative journalist for the latest issue of Index on Censorship magazine, which is themed on the risks of reporting worldwide.

Juma was arrested in January for posting information on social media about a recent attack on the Kenyan Defence Force by the Al-Shabaab militant group. Juma revealed that, according to a credible source within the KDF, 103 soldiers had been killed in an attack on the Kenyan army base in El Adde, Somalia.

The journalist was later arrested and faced charges of “misuse of a telecommunication gadget”. After being grilled by police and detained for two days, he was released without charge but has since gone into hiding, fearing that his reporting is angering the authorities.

Listen to Einashe explaining the significance of this case on the Soundcloud above. The full article, written by Einashe, is in the latest issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Print copies of the magazine are available here, or you can take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions. Copies are also available at the BFI, the Serpentine Gallery, MagCulture, (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester) and on Amazon. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship continue its fight for free expression worldwide.