4 Oct 2017 | Mapping Media Freedom, Media Freedom, media freedom featured, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

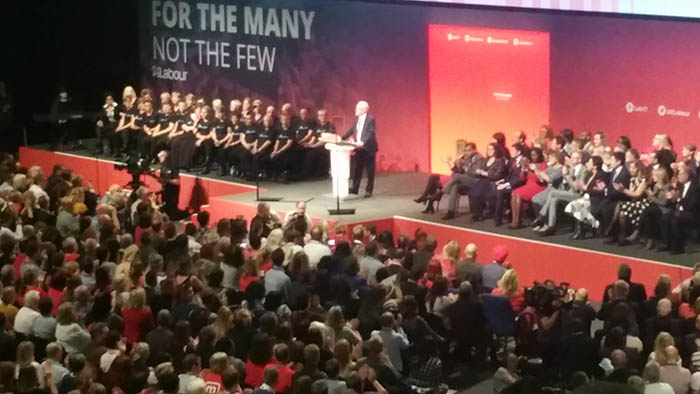

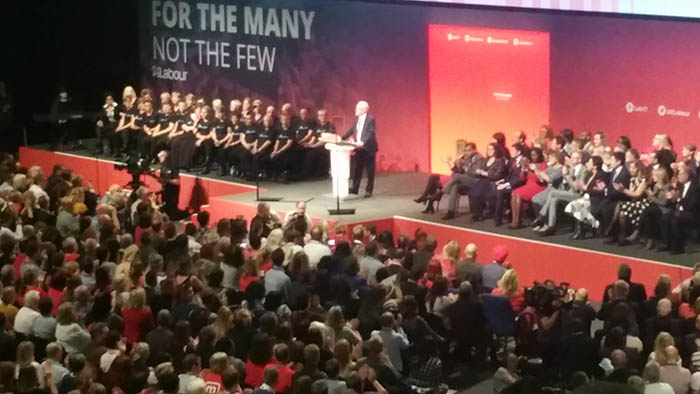

Jeremy Corbyn speaks at Labour Party conference in Brighton, September 2017. Credit: DaveLevy/Flickr

During his first speech at conference as Labour Party leader in September 2015, Jeremy Corbyn called for an end to “personal abuse” and urged delegates to “treat people with respect”.

“Cut out the cyber-bullying and especially the misogynistic abuse online,” he added. “I want kinder politics.”

Two years on the message hasn’t gotten through.

On 24 September 2017, the second day of this year’s party conference, BBC political editor Laura Kuenssberg was assigned bodyguards after receiving abusive threats online.

The BBC had also decided to bolster Kuenssberg’s personal protection during the general election in June after she faced threats over alleged bias in her reporting surrounding Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn. She has also been accused of partiality by Conservative and Ukip supporters.

“It is unprecedented that a journalist would need protection to do her job covering a political conference in the UK, which makes this all the more troubling,” Hannah Machlin, project manager for Index on Censorship’s’ Mapping Media Freedom project, said. “Laura’s case indicates that sexist online abuse against women journalists has become part of the job, and it’s affecting not only the safety of reporters but also a functioning free press.”

Two other journalists were refused entry altogether to the conference. On 23 September, Sussex police refused to give Huck magazine editor Michael Segalov a press security clearance required to attend. Segalov wrote that he applied for press accreditation three months prior to the conference but was informed the evening of 19 September that it had been denied based on the police’s refusal to grant him security clearance.

“Rather than provide reasons and rationale for our journalistic freedom being curtailed, the police said they would not divulge why they made their call,” Segalov wrote. He has never been arrested, charged or convicted of any crime.

“This might be a single incident, but the repercussions should it go unchallenged are worrying. The police restricting the rights of a journalist from attending a political event without giving any rationale, basis or reason puts our civil liberties on the line.”

On 24 September, Michael Walker, a left-wing journalist working for Novara Media, was also barred from entering by police.

“Barring reporters is a form of censorship,” Machlin added. “Political parties interfering with access to events undermines key parts of democracy and sends a clear message from the labour party to all other journalists.”

Earlier this year, Corbyn’s press team barred Buzzed from campaign events. On 9 May, in the run-up to the general election, a senior Corbyn aide told BuzzFeed News political editor Jim Waterson that his access was limited and that the website’s access to the Labour leader would be limited for the rest of the campaign. This was because of an interview with Corbyn published on 8 May had “disrupted media coverage of Labour’s launch event”, the website reported.

Buzzfeed published a piece quoting Corbyn that he remain as the party’s leader even if he lost the election. Corbyn told the BBC he had only said he would stay in power because they would win. BuzzFeed then published an extract of the interview, which showed they had quoted him accurately.

Waterson later regained access to the leader.

Such violations to media freedom are not limited to the Labour Party, however. Also in the run-up to the election, three journalists for Cornwall Live were shut in a room, prevented from filming and severely limited on what questions they could ask during Conservative prime minister Theresa May’s visit to a factory in Cornwall.

A reporter from Cornwell Live who was live-blogging the event wrote: “We’ve been told by the PM’s press team that we were not allowed to stand outside to see Theresa May arrive.”

On two occasions in April 2017, Conservative-run Thurrock Council in Essex said they would restrict access to journalists who “do not reflect the council’s position accurately”.

In the wake of the Grenfell Tower fire in June, the Kensington and Chelsea Council, which has been Conservative-run since 1964, tried to prevent journalists from attending its first after the atrocity. The council had sought to exclude the public and media from the cabinet meeting, arguing their presence would risk disorder. But after a legal challenge from five media organisations, a high court judge ordered the council to allow accredited journalists to attend half an hour before the meeting was due to start. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1507044011187-4d3c340a-bdf9-4″ taxonomies=”6564″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

24 Sep 2015 | mobile, News and features, United Kingdom

I have been away, with thankfully intermittent internet access limiting my access to top quality prime minister/pig-related punning, so apologies if you see your fantastic pun replicated here. Entirely unintentional.

If you’ve been even more away than me, a quick recap of the story that will never die: Conservative peer Lord Ashscroft, he of the polls, has brought out a book — along with the Sunday Times’ Isabel Oakeshott — about Prime Minister David Cameron. Among the accusations levelled at Cameron are that Conservative colleagues see Libya as “his Iraq”, that he attempted to get a friend off criminal charges and that he listened to Supertramp.

No one cares about any of that stuff at all. The one thing everyone is, frankly, still cracking up about was the revelation in Monday’s Daily Mail (which is serialising the book) that Cameron, while at university, took part in an initiation ceremony for a drinking club which involved putting the parts of a prime minister we shouldn’t think about in a pig’s head. The head, it should be noted, was not attached to a live animal.

This is obviously enormously odd, and hilarious. I’m not about to get po-faced about sexual deviance, or how Cameron is screwing the country even more than he did that pig head, or, as I have seen, ponder the dark occult symbolism of our elite universities. Because, really, it’s not symbolic of anything apart from students being utter, utter clowns.

That is, of course, assuming that it is true. Something that is by no means certain. The source for the allegation is apparently an Oxford contemporary of Cameron’s who is now an MP, who reckons he has seen a photograph of a compromised future prime minister engaging with the hog’s head.

Now, “a bloke I know reckons he saw a photo” may be a decent threshold of proof for a pub anecdote (bonus points if the bloke is upgraded from mere bloke to “my brother’s friend” lending a real tangibility): but this is not presented as a pub anecdote, and as a presentation of proof, it doesn’t really do: it would never stand up in court, as the pig said to the aspiring Piers Gaveston member.

Given that, should David Cameron sue? Tricky business. Fine things that our new libel laws now are, does one really want a court case hinging on whether or not one performed indecencies on swine flesh a lifetime ago? Even if you win, do you want to go down in history as the Prime Minister who definitely didn’t have sex with a dead pig? One may as well buy a t-shirt with “not a wrong ‘un, honest” written on it.

In an interesting Guardian article, Damian McBride, a former spin doctor for Cameron’s predecessor Gordon Brown, wonders why Cameron’s people have not issued an official dismissal of “Piggate”, or any of the other allegation in the Ashcroft/Oakeshott book, pointing out that “In the absence of an instant bucket of water, the story has caught fire over the past two days. Not only that, it’s allowed other newspapers to declare open season on Cameron’s private life, as we see from today’s ‘coke parties’ splash in the Sun.”

I can understand McBride’s point, but I do think that Cameron’s people did the right thing here, mostly because if they start engaging with the specific allegations in the book, sooner or later they come round to having to confirm or deny the porcine partnering. We’re back to square one.

Where’s the free speech rub in this, I hear you ask? Well, there’s the simple fact that you have to be able to take as well as give in these matters. During Jeremy Corbyn’s ascendance to power as Labour leader, many of his followers complained daily of the outrageous “smears” of the dread MSM. In his leadership acceptance speech, Corbyn himself complained of the “most appalling levels of abuse from some of our media over the past three months” apparently suffered by him and his family during his campaign, which seemed to amount to some reheated speculation about the cause for a split from a previous partner and the shocking, shocking revelation that he ate baked beans out of a tin. Before you write in, questioning Corbyn’s public declarations and political associations is a necessary and important function of the press. People who complained about Corbyn’s apparent abuse now seem totally OK repeating allegations made by a wealthy Conservative peer in the pages of the Daily Mail. Which is fine, but just be aware of the mismatch. (To his credit, Corbyn appears to have entirely avoided the topic, though Cameron was lucky that there was no PMQs this week due to conference season).

Public figures will be open to scorn, ridicule, abuse and more. Their every move, from even before they aspired to power, will be pored over for clues and significance (as has been done by, for example, the New Statesman’s Laurie Penny with Cameron’s curious incident avec le cochon). It may happen, as we grow into an age where no one is embarrassable anymore, because they’ve already put everything on Instagram, that these stories will no longer make any sense. But for now they still happen, and on balance, it is good that they do.

When it comes to public figures, we should err away from caution. The extremely wealthy Ashcroft’s intervention with this string of what the KGB used to call Kompromat against Cameron is not perhaps the best example of the old speak-truth-to-power schtick (it’s more power calling other power names because it didn’t get what it wanted — a cabinet post, allegedly), but nonetheless, being rude about powerful people is very important and even cathartic — ask any cartoonist.

The rush of schweinficker jokes may have done little more than lifted the autumn gloom, but it’s strangely satisfying that in a democracy we can openly mock our leaders, safe in the knowledge that whatever they do, they’ll only make it worse for themselves.