Salil Tripathi: As Singapore turns 50, is it on the cusp of becoming different?

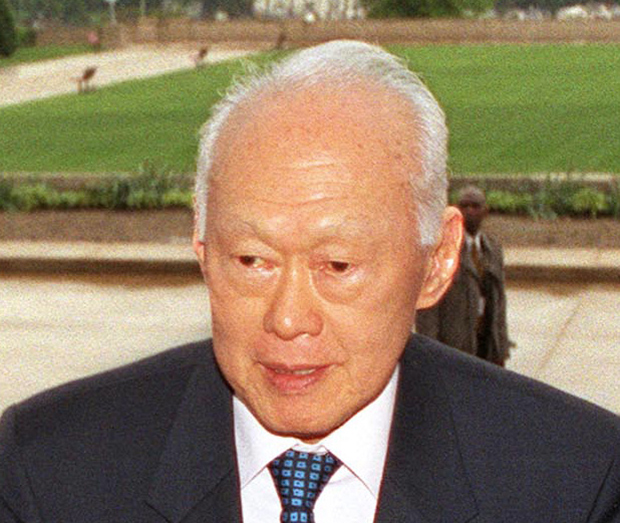

Singapore’s founding father and long-serving Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, who died in March. (Photo: “Lee Kuan Yew” by Robert D. Ward – Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons)

Salil Tripathi has joined Index as an online columnist and will be contributing monthly

The golfing phrase “OB markers” has a special meaning in Singapore. Short-hand for what is “out-of-bound,” it lays out, informally, the limits of what can be said, and if you’ve lived long enough in Singapore, you are supposed to know what those markers are, and where they are.

Singapore has laws regulating speech, some of which are inherited from the British era, while others were refined to suit Singapore’s governance model, which many have described as soft authoritarianism, associated with Lee, who died in March at 91, led his People’s Action Party to successive electoral victories since independence in 1965, and the party has remained in power since. Goh Chok Tong succeeded Lee as prime minister in 1990, and Lee’s son, Lee Hsien Loong, has been prime minister since 2004.

The genius of the principle of OB markers lies in its ambiguity – the markers are not clearly defined; it is incumbent on the journalist to figure out what can and cannot be said; it keeps everyone guessing. The model has suited Singapore well for the past five decades. The local media, much of it owned by companies close to the government, has little problem with it. Many international publications have also complied with the system. (Most foreign correspondents based in Singapore have regional responsibilities, and South-East Asia does offer a range of interesting stories. Unlike those countries, Singapore’s post-independence history has been far less dramatic.)

Besides, when foreign publications published stories or commentaries critical of Singapore, they faced lawsuits. Far Eastern Economic Review, where I worked for some of my eight years there, was combative; it not only lost lawsuits and its circulation was restricted, as was the case with some other publications.

This year marks a watershed – the republic celebrates its 50th anniversary, but the joy is clouded by Lee’s passing. Many have credited him with building modern Singapore; those who lament Singapore’s stunted politics say it is the result of his style of governance.

Is Singapore on the cusp of becoming different?

In four recent cases Singaporeans have tested the limits of freedoms they can take for granted. A video, a film, a blog and a graphic novel have pushed at the boundaries of what can be said, and the government realises that it cannot simply ban these, because banning is no longer that simple, and Singaporeans today are better-educated and more demanding than in the past. Singaporeans no longer watch films only in theatres or on television, nor buy books only in shops, and nor do they consume news and opinions only through newspapers and magazines. Furthermore, better-educated, articulate Singaporeans want to be treated as thinking adults who can make up their own minds. How Singapore deals with this change will determine what kind of society Singapore will become.

Amos Yee is a teenager with an attitude. In a controversial video he posted online within days of Lee’s passing, he made highly critical and disparaging remarks about Lee. Yee is precocious and strident, and doesn’t fit the image of the shy, polite, obedient Singaporean with a neat hair-cut that the republic has tried so hard to groom. With an accent that sounds North American and a vocabulary that would make his grandparents cringe, he attacked Lee’s political legacy and economic record, pointing out economic disparities and the silencing of the opposition.

But he also criticised Christianity, and for that, Yee was arrested and charged with showing “intention of wounding” religious feelings. To be sure, many ruling party supporters were incensed over his political criticisms. One man made crude physical threats online. (Making violent online threats is a crime in Singapore). Another man slapped Yee when he was on his way to court (the man was subsequently arrested, tried, and jailed). Yee’s attitude did not help; his lawyer was exasperated by Yee’s recalcitrant behaviour (including flouting bail conditions), and it was hard to figure out if he should be tried as an adult – and punished accordingly – or sent for psychiatric evaluation. In the end, he was sentenced, but as he had spent more time in remand than his sentence, he was released. The Wall Street Journal wrote the case showed Singapore’s struggle to adapt its tradition of censorship to the realities of the digital era.

Yee presented a unique dilemma for Singapore. The government is used to respond robustly to critics who are political rivals, academics, or foreign journalists. It has sued opposition politicians, some have become unemployable, and some have had to leave the country, as their visas are not renewed. But here was a boy, not yet an adult; he was not old enough to be part of the mandatory military service; and he was being deliberately provocative. But how could a state go after a teenager who has acted like a brat?

Roy Ngerng

Roy Ngerng is a blogger who has criticized the government’s handling of the mandatory Central Provident Fund in his blogs. As an activist, he has campaigned for greater equality through higher public spending. Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong sued Ngerng for defamation, and during his recent trial to assess damages, Lee’s lawyer Davinder Singh sought aggravated damages. Ngerng described himself as a man of limited means and argued his own case, and said he had apologized; Lee’s lawyers said the apology was not sincere enough. At one point, Ngerng broke down in the court. In another case, Tan Shou Chen, who acts in an ongoing show, LKY: The Musical wrote a blog where he claimed that the government had interfered with the script. The government denied it, and Tan took down his post. The show is running till 16 August.

Tan Pin Pin has made a film called To Singapore With Love, which showcases the lives of left-leaning dissidents who had challenged Lee in the 1960s. In the years leading up to Singapore’s independence, Lee had initially allied with the left, but later parted company. It was a period of regional turmoil, with the war raging in Vietnam and spreading to Indo-China, and there were real fears of Communism spreading across South-East Asia. These dissidents left Singapore and went into exile; a few have since died, and others are not allowed to return to Singapore. Tan’s film gives voice to those individuals, portraying them sympathetically as nationalists who saw Singapore’s future differently.

Singapore has banned the film from public screening because it “undermined national security”, but private screenings are allowed in Singapore. A week after its ban last September, more than a hundred Singaporeans took buses to Johor Baru, the Malaysian city across the causeway that links Singapore and Malaysia, and saw it there. Tan challenged the ban but she lost. The film has been shown at international festivals and while it can be bought online overseas, it cannot be shipped to a Singaporean address.

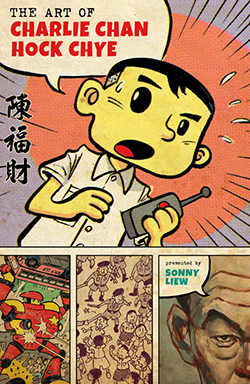

Finally in June, Singapore’s National Arts Council withdrew its grant made to artist-illustrator Sonny Liew, who had published a graphic novel called The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye. The council said the way the graphic novel retold Singapore’s history undermined public authority. Interestingly, it did not ban the book; the council wanted its money back. (The publisher complied; the graphic novel sold out instantly and reprints were ordered).

Finally in June, Singapore’s National Arts Council withdrew its grant made to artist-illustrator Sonny Liew, who had published a graphic novel called The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye. The council said the way the graphic novel retold Singapore’s history undermined public authority. Interestingly, it did not ban the book; the council wanted its money back. (The publisher complied; the graphic novel sold out instantly and reprints were ordered).

These cases show the constant tussle over where those OB markers lie in Singapore isn’t over. In the past, it was clear: there were bans, prosecutions, bankruptcies, fines and jail terms. In the post-LKY Singapore, rules are changing and those markers are shifting.

Singapore’s leaders lay great store in business school principles and terms, such as feedback loops. They will have to ensure that those loops are not shut, and listen to what Singaporeans are saying. That is possible in an environment where people are free to draw, write, and speak. There is an east Asian saying that “the bamboo shoot that grows tall gets chopped first.” Chopping that bamboo shoot is no longer an option. If the government listens more, Singapore will benefit. True, some teenagers will throw tantrums, but that’s part of growing up.

Index on Censorship magazine has been covering Singapore since 1975 when Simon Cassady reported on Lee Kuan Yew & the Singapore media: Purging the press.

This column was posted on 30 July 2015 at indexoncensorship.org