9 Sep 2020 | Events

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”114632″ img_size=”large”][vc_column_text]Banned Books Week 2020 (27 September–3 October) takes place four months after George Floyd’s murder led to a global resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement, and three months after the publication of the Rethinking Diversity in Publishing report, which demonstrated the particular challenges writers of colour still encounter.

Taking Banned Books Week’s theme as its starting point – a celebration of the freedom to read – our panel take stock of the commitments to inclusion and representation that have been made in publishing over the last few months. With representatives from the books industry – from editors to heads of writers’ organisations – this webinar will explore how we work together to celebrate marginalised voices in literature.

Adam Freudenheim is the Publisher and Managing Director of Pushkin Press. He has worked in publishing since 1998 and was Publisher of Penguin Classics, Modern Classics and Reference from 2004 to 2012. Adam joined Pushkin in May 2012, where he has launched the Pushkin Children’s Books, Pushkin Vertigo and ONE imprints, and he is particularly proud to have published the first translation of The Letter for the King by Tonke Dragt and Jakob Wegelius’s dazzlingly original The Murderer’s Ape; as well as to have introduced the acclaimed American short story writer Edith Pearlman to British readers (with Binocular Vision) and Israeli writer Ayelet Gundar-Goshen (her most recent novel is Liar).

Sharmaine Lovegrove is the Publisher of Dialogue Books, the UK’s only inclusive imprint, part of Little, Brown Book Group and Hachette UK. Dialogue Books is a home for a variety of stories from illuminating voices often missing from the mainstream. Sharmaine was the recipient of the Future Book Publishing Person of the Year 2018/19 and is inspired by innovative storytelling, and has worked in public relations, bookselling, events management and TV scouting. She was the literary editor of ELLE and set up her own bookshop and creative agency when living in Berlin. Sharmaine serves on the boards of The Black Cultural Archives, The Watershed and is an founding organiser of The Black Writers Guild. Home is London, she lives in Berlin and her roots are Jamaican – Sharmaine is proud to be part of the African diaspora and books make her feel part of the world.

Claire Malcolm is the founding Chief Executive of the literary charity New Writing North where she oversees flagship projects such as the David Cohen Literature Award, Gordon Burn Prize, the Northern Writers’ Awards and Durham Book Festival and award-winning work with young people. She works with partners from across the creative industries and charity and public sectors including Penguin Random House, Hachette, Faber and Faber, Channel 4 and the BBC to develop talent in the North. Claire is a trustee of the reading charity BookTrust, the Community Foundation Tyne and Wear and a board member of the North East Cultural Partnership.

Aki Schilz is the Director of The Literary Consultancy, which runsediting services, mentoring and literary events. At TLC Aki co-ordinates partnerships and programmes, including running the Quality Writing for All campaign which focuses on inclusivity and diversity. In 2018 Aki was named as one of the FutureBook 40, a list of people innovating the publishing industry, and was also nominated for an h100 Award for her work with the #BookJobTransparency campaign. In 2019 she was shortlisted for the Kim Scott Walwyn Prize for women in publishing, and in 2020 was named as one of INvolve’s Top 100 Ethnic Minority Future Leaders.

In partnership with the Royal Society of Literature, English PEN, the British Library and the Black Writers’ Guild.

This event is FREE for all. Please register here.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”114627″ img_size=”large”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Banned Books Week is an annual event celebrating the freedom to read.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text][/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

9 Sep 2020 | Events

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”114628″ img_size=”large”][vc_column_text]In the wake of George Floyd’s murder and the resultant global Black Lives Matter protests, it has been clearer than ever before that the voices of some are prioritised to the exclusion of others.

As part of Banned Books Week 2020 – an annual celebration of the freedom to read – Index is partnering with the Royal Society of Literature, the British Library and English PEN, bringing together a panel of writers who have committed to sharing their stories, to creating without compromise, and to inspiring others to do the same. We ask what ‘freedom’ means in the culture of traditional publishing, and how writers today can change the future of literature.

Urvashi Butalia is Director and co-founder of Kali for Women, India’s first feminist publishing house. An active participant in India’s women’s movement for more than two decades, she holds the position of Reader at the College of Vocational Studies at the University of Delhi.

Rachel Long is a poet and founder of Octavia Poetry Collective for Womxn of Colour, based at the Southbank Centre. Her first collection My Darling from the Lions, shortlisted for the Forward Prize for Best Collection 2020, explores the intersections of family, love, and sexual politics. She is co-tutor on the Barbican Young Poets programme.

Elif Shafak is an award-winning British-Turkish novelist, whose work has been translated into 54 languages. She is the author of eighteen books; her latest, 10 Minutes 38 Seconds in this Strange World, was shortlisted for the Booker Prize and the 2020 RSL Ondaatje Prize. She holds a PhD in political science and she has taught at various universities in Turkey, the US and the UK. She was elected an RSL Fellow in 2019.

Jacqueline Woodson is the author of more than two dozen award-winning books. She is a four-time National Book Award finalist, a four-time Newbery Honor winner, a two-time NAACP Image Award winner, a two-time Coretta Scott King Award winner, recipient of the 2018 Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award, the 2018 Children’s Literature Legacy Award and the 2020 Hans Christian Andersen Award.

Public tickets can be booked through the British Library (£5).[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”114627″ img_size=”large”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Banned Books Week is an annual event celebrating the freedom to read.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text][/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

20 Sep 2013 | Africa, News and features, Uganda

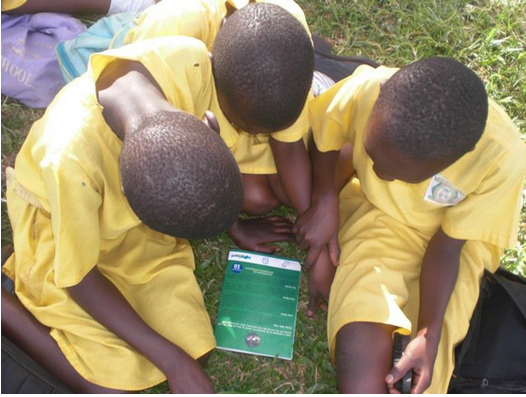

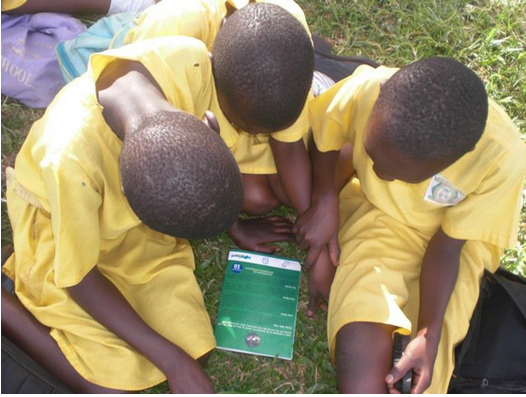

The heroine of The Little Maid, Viola, is an eight-year-old Ugandan girl who lives with her destitute grandmother and dreams of going to school. Instead, she is sent to live with her aunt, who promises to pay her school fees if Viola works for her first. Viola becomes a maid, forced to wash clothes, scrub the bathroom, cook and live in servants’ quarters. But every day when her cousins’ tutor arrives, she crawls underneath the dining room table to eavesdrop on the lessons. Eventually Viola learns to read and write and escapes the clutches of her evil aunt, who is found guilty of child abuse and child slavery and ordered to school her niece.

The heroine of The Little Maid, Viola, is an eight-year-old Ugandan girl who lives with her destitute grandmother and dreams of going to school. Instead, she is sent to live with her aunt, who promises to pay her school fees if Viola works for her first. Viola becomes a maid, forced to wash clothes, scrub the bathroom, cook and live in servants’ quarters. But every day when her cousins’ tutor arrives, she crawls underneath the dining room table to eavesdrop on the lessons. Eventually Viola learns to read and write and escapes the clutches of her evil aunt, who is found guilty of child abuse and child slavery and ordered to school her niece.

It could be a true story. In Uganda there are an estimated 2.75 million children engaged in work, although not many of those will have the happy ending. But The Little Maid is a work of fiction, written by Oscar Ranzo, a Ugandan social worker turned author who has penned five children’s books. Now, The Little Maid is being distributed to schools across the country low-cost (5,000 Ugandan shillings or $1.90 each) through his Oasis Book Project. The project aims to improve the reading and writing culture in Uganda and provide school-children with entertaining but educational stories to which they can relate. Ranzo sells most of his books to schools, with the proceeds used to publish more titles. However, he also donates copies to more impoverished areas.

In 1969, Professor Taban Lo Liyong, one of Africa’s best-known poets and fiction writers, declared Uganda a ‘literary desert’. “What we want to do with this project is create an oasis in the desert,” explains Ranzo. “That’s why I called it the Oasis Book Project.”

The small print

Excluding textbooks, there are only about 20 books published in Uganda annually. According to a study last year by Uwezo, an initiative aimed at improving competencies in literacy and numeracy among children aged six to sixteen years in East Africa, more than two out of every three pupils who had finished two years of primary school failed to pass basic tests in English, Swahili or numeracy. For children in the lower school years, Uganda recorded the worst results.

Growing up in the 1970s and 1980s, Ranzo was privileged to have a grandfather who had a library and attended a private school that held an after class reading session. He was a particularly avid fan of Enid Blyton’s Famous Five series.

“But Mum was a nurse and she wanted me to be a doctor. I wanted to pursue literature and she told me ‘no you can’t do that’, so I did sciences,” says Ranzo, stressing that literature, which remains optional in secondary school, is not taken seriously in Uganda.

Furthermore, many local publishers do not see writing fiction as profitable. “They’d rather publish textbooks and get the government to buy them,” Ranzo explains.

His books are available in two central Kampala bookshops for 8,000 shillings ($3). But in the past 15 months fewer than 20 have moved from the shelves, while he has sold over 3,000 to 20 schools in three districts.

Fiction imitating life

Saving Little Viola, his first book in which the female protagonist, Viola, was introduced, was published in 2011 by NGO Lively Minds. The story ends with Viola being saved by her best friend from two men who want to use her for a ritual sacrifice. UNICEF funded its distribution to 36 primary schools across Uganda as part of a child sacrifice awareness programme.

The primary aim of the Oasis Book Project is to encourage reading, although Ranzo admits he would like people to discuss his stories, which have themes close to his heart. Children being forced into work, the theme of The Little Maid, is something he has witnessed himself.

“Many kids are brought from villages to work as maids in homes in towns or cities, and the treatment they are subjected to is terrible in many cases,” says Ranzo.

His next book, The White Herdsman, which will be released in 2014, deals with the impact of oil production on communities, a timely subject for Ugandans with oil production expected to start in 2016. The book tells the story of a village where water in the well has turned black after an oil spill. A witchdoctor blames the disaster on an albino child.

Ranzo’s stories have been welcomed at Hormisdallen Primary, a private school in Kamwokya, Kampala. English teacher Agnes Kasibante, speaking to Think Africa Press, praises the book’s impact. “It’s actually a big problem in Uganda, most children don’t know how to read. At least those books give them morale to continue loving reading,” she says.

Ranzo has also penned Cross Pollination, a collection of fictional stories for adults about the spread of HIV in a community. According to a recent report, Uganda may not meet its target to increase adult literacy by 50% by 2015.

“I’ve worked in a big multinational company where people have jobs but they can’t write. Reading can help develop this,” says Ranzo, who is currently attending the University of Iowa’s 47th annual International Writing Program (IWP) Fall Residency.

Uganda’s literary comeback

Jennifer Makumbi, 46, a Ugandan doctoral student at Lancaster University, is one of a new generation of Ugandan authors. She won the Kwani Manuscript Project, a new literary prize for unpublished fiction by Africans, for her novel The Kintu Saga. She said Taban Lo Liyong’s description of Uganda as a literary desert was “heartbreaking, especially as in the 1960s Uganda seemed to be poised to be a leading literary producer”.

“But perhaps it is exactly this description that is pushing Ugandans to write in the last ten years,” she continues. “Yes, we have not caught up with West Africa yet but… there are quite a few wins.” In recent years, two female Ugandan authors, Monica Arac de Nyeko and Doreen Baingana, won the Caine Prize for African Writing and the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize respectively. Makumbi’s Kwani prize adds her to a list of eminent Ugandan authors.

Makumbi is optimistic about the future of Ugandan literature: “These I believe are indications that Uganda is on its way.”

This article was originally published on 17 Sept 2013 at Think Africa Press and is reposted here by permission.

28 Dec 2012 | India

The film of Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children is set to be released on 1 February. If the team behind the movie adaptation is at all nervous about screening the film they have good reason. Rushdie, who wrote the screenplay, and has been the literary face for freedom of expression for years, has a tumultuous history of censorship with India.

The Booker prize-winning book is about two children, born at the stroke of midnight as India gained its independence. Their lives become intertwined with the life of this new country.

One of the figures in the book, The Widow, was based on former Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. In the book, the character, through genocide and several wars, helps destroy Midnight’s Children. Gandhi had imposed a widely-criticised State of Emergency in India.

In an interesting turn of events, Gandhi threatened Rushdie libel over a single line. That line suggested that Gandhi’s son Sanjay had accused his mother of bringing about his father’s heart attack through neglect. Rushdie settled out of court, and the single line was removed from the book.

The movie adaptation of Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children

The real controversy that followed, the one that changed Rushdie’s life completely, came after the 1988 release of his book The Satanic Verses. While the Iranian supreme leader Ayatollah Khomeini had issued a fatwa against Rushdie and called for his execution (citing the book as blasphemous), the author saw many countries, including India, indulge in their own brand of censorship.

As has been revealed in Rushdie’s memoir Joseph Anton, the author felt the Indian government banned his book without much scrutiny. The Finance Ministry banned the book under section 11 of the Customs Act, and in that order stated that this ban did not detract from the literary and artistic merit of his work. Rushdie, appalled at the logic penned a letter to the then prime minister of India, Rajiv Gandhi, stating:

Apparently, my book is not deemed blasphemous or objectionable in itself, but is being proscribed for, so to speak, its own good… From where I sit, Mr Gandhi, it looks very much as if your government has become unable or unwilling to resist pressure from more or less any extremist religious grouping; that, in short, it’s the fundamentalists who now control the political agenda.

Rushdie was right, of course. Years later, in 2007, he attended the first Jaipur Literary Festival in India unnoticed. Without any security or fuss, he arrived unannounced, mingling with the crowd. Things had changed dramatically by 2012, when Rushdie’s arrival to the now must-attend literary festival was much publicised, and predictably attracted controversy.

Maulana Abul Qasim Nomani, vice-chancellor at India’s Muslim Deoband School, called for the government to cancel Rusdie’s visa for the event as he had annoyed the religious sentiments of Muslims in the past. (Incidentally, Rushdie does not need a visa to enter India as he holds a PIO — “Person of Indian Origin” — card.)

The controversy escalated quickly, with the organisers first attempting to link Rushdie via video instead of having him physically present, but then cancelling the arrangement when the Festival came under graver physical threat. It was a sad day for freedom of expression in India, especially considering the fact that many, including Rushdie felt these moves were politically motivated because of upcoming elections in Uttar Pradesh, where the Muslim vote is very important. The government vehemently denied these claims.

Liberals in India were shocked at the illiberal values that the modern India state espoused, feigning to not be able to protect a writer and a festival against the threats of protestors. Shoma Chaudhary of Tehelka wrote:

The trouble is nobody any longer knows what Rushdie was doing in The Satanic Verses: neither those who are offended by him, nor those who defend him. Almost no one, including this writer, was given a chance to read the book.

Later in the year, initial press reports around Midnight’s Children revealed that the film could not find a distributor in India. The production team thought it might be a case of self-censorship as the film featured a controversial portrayal of Indira Gandhi. However, PVR Pictures, a major distributor in India, has plans to release the film in the country in February 2013.

31 years after the Midnight’s Children hit the stands, and the same year as he was bullied into cancelling a visit to a literary festival, it seems Salman Rushdie will yet again challenge Indian society. It remains to be seen if he will, yet again, become a pawn in the internal politics of the country.

The heroine of

The heroine of