15 Mar 2024 | News and features, Opinion, Ruth's blog, United Kingdom

For those of us in the British Labour movement this month has been a period of reflection – on the pain, anger and pride associated with an industrial action which became intrinsically linked with people’s sense of place, community and politics in the post war period.

In the heart of South Yorkshire, at the Cortonwood colliery, a new page of history was written. On 6 March 1984, the first sparks of the miners’ strike were ignited when miners at the colliery, which had been established in 1873, withdrew their labour in protest at plans announced by the National Coal Board to close the pit.

For British miners and their trade union, the NUM, this was the first act of a plan to start systematically closing UK coal mines. The closures were a direct threat to people’s livelihoods and the very essence of their communities.

This isn’t just a pivotal moment in British industrial history but was also a defining moment for the development of my social value system. My grandfather was a striking miner at the Bilston Glen pit in Scotland and one of my earliest memories is collecting food in the East End of London to send to striking miners.

Forty years on from the miners’ strike it’s important that we remember not just the damage done to people and families, but how powerful interests can combine to subjugate and silence those standing up for their rights.

While some may not immediately recognise industrial action as a form of freedom of expression, I would argue that withdrawal of labour is the ultimate expression of your freedom. At its core, industrial action embodies the collective voice of workers asserting their rights and advocating for their economic interests. Whether through strikes, protests, or other forms of organised resistance, workers exercise their agency to challenge unjust conditions, demand fair treatment, and negotiate for better terms of employment. This expression is not merely confined to vocal dissent but extends to the very actions that disrupt the status quo, thereby amplifying the voice of the marginalised and empowering individuals to challenge entrenched power structures. In this light, industrial action emerges as a potent manifestation of freedom of expression, serving as a vital instrument for social change and democratic participation in shaping the contours of labour relations.

All that was put at risk in 1984 when senior government ministers and certain sections of the media conspired to paint those taking industrial action as “the enemy within”. A view perpetuated by the Prime Minister of the time, Margaret Thatcher. Handwritten notes from the Margaret Thatcher archives show her thinking:

“Since Office. Enemy without – beaten [Galtieri] & resolute strong in defence. Enemy within – Miners’ leaders… Liverpool and some local authorities – just as dangerous… in a way more difficult to fight… just as dangerous to liberty.”

The damaging effects of this rhetoric can still be seen and felt today.

The miners’ strike lasted for 11 months, 3 weeks and 4 days. 11,291 miners and allies were arrested on pickets and at demos. Communities were devastated, families went hungry and proud men lost their livelihoods forever.

There are many chapters in the story of the Miners’ strike, but the one where there are still more questions than answers is the Battle of Orgreave. The events at Orgreave on 18 June 1984 mark the lowest and most violent point in British industrial relations, where the principle of policing by consent nearly collapsed and the police were arguably used as a tool by the state to squash dissent. The media adopted a one-dimensional narrative on events which framed the striking miners and picketers as the aggressors and the police as the innocents. This portrayal is increasingly being challenged as a more comprehensive narrative emerges, prompting critical reflection on the broader implications of industrial disputes and the state response.

For me the miners’ strike of 1984 stands as a poignant reminder of the enduring struggle for freedom of expression and the pivotal role it plays in safeguarding democratic values. By reflecting on the strike and the power imbalance typically deployed, we must remember the sacrifices made by those who fought tirelessly for their rights in the face of formidable opposition. It serves as a sobering lesson on the dangers posed by governments and vested interests seeking to undermine this fundamental freedom.

As custodians of democracy, we are duty-bound to uphold and defend the right to express dissent, knowing that its suppression can lead to the erosion of civil liberties and the consolidation of power in the hands of the few. Thus, the miners’ strike of 1984 stands not only as a testament to past struggles but also as a call to vigilance in protecting the freedoms that form the bedrock of our society.

16 Oct 2014 | News and features, Politics and Society, Religion and Culture, United Kingdom

Thirty years ago this week a bomb exploded in the Grand Hotel, Brighton, where the then prime minister, Margaret Thatcher, and much of her cabinet were staying during Conservative party conference.

The bomb had been planted a month previously by IRA member Patrick Magee, with the intention of assassinating the prime minister. Thatcher escaped, but others did not. Five party members died. Others, including Margaret Tebbit, wife of Thatcher’s rottweiller Norman Tebbit, were left disabled.

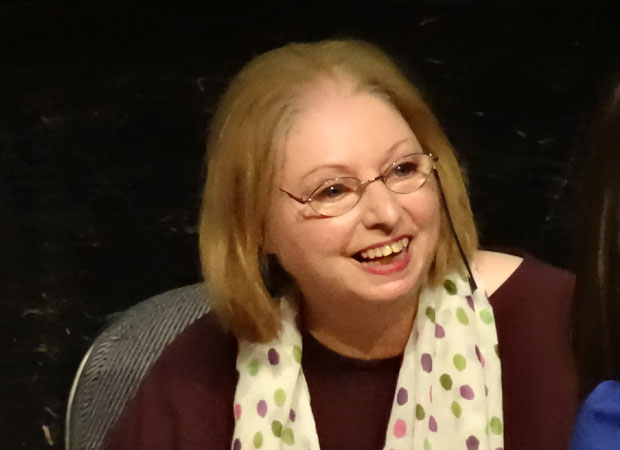

The whereabouts of then-32-year old aspiring novelist Hilary Mantel at the time were not known, but we do now know that she herself was thinking about killing Thatcher as the IRA was planning the Grand bombing.

Last week, at the Royal Festival Hall, a solid concrete building that looks as if it could survive the combined explosive attentions of the IRA, Al Qaeda and a reanimated Fred Dibnah, Mantel discussed her own Thatcher assassination plot, which was published this year in the form of a short story that she had started over 3 decades ago.

“People have worked so hard to take offence at this story,” the Wolf Hall author pointed out, adding mischievously, “If only they would go through my extensive back catalogue it would keep them in fury for the rest of their lives.”

Mantel’s assassination fantasy is an enjoyable piece of suburban noir in which an IRA sniper attempts to use a Windsor woman’s window as a hide to take a shot at Thatcher. It’s interesting in that one finds the narrator and the gunman jockeying for position about their right to revile Thatcher as they do: who is more Irish? who is more Northern? Who is more affected by this terrible woman?

But ultimately it’s an almost Tales-Of-The-Unexpectedish story about extraordinary things happening to ordinary people.

Mrs Thatcher’s friend Lord Bell was horrified by Mantel’s story and her subsequent interview in The Guardian, where Mantel described seeing Thatcher leaving the hospital in 1983, saying that “if I wasn’t me, if I was someone else, she’d be dead”. Lord Bell angrily announced: “If somebody admits they want to assassinate somebody, surely the police should investigate. This is in unquestionably bad taste.”

The Daily Mail’s Stephen Glover was equally apoplectic: “Mantel’s contribution is peculiarly damaging because, while she appears so mild-mannered, her message is interpretable as a deadly one. If you don’t like your democratically elected leaders, who operate within the rule of law, you can always think about assassinating them.”

What Bell and Glover both seem to have failed to grasp here is the difference between thinking about something and doing it, or even the difference between thinking about doing something and plotting to do it.

Thinking about doing things one would not normally do is often known as “imagining”, and is quite crucial to the creative process. It’s an essential part of humanity that we can think beyond ourselves. It’s what allows us to empathise and sympathise; we may not be familiar with a specific set of circumstances, but we can, at least in part, imagine what it would be like to be placed in certain circumstances. I have never been homeless, but I can imagine that I wouldn’t like it. I can even imagine what might go through the head of someone I profoundly disagree with.

It was by sheer coincidence that the night before Mantel spoke at the Royal Festival Hall, Salman Rushdie received the PEN Pinter prize at the British Library.

While Mrs Thatcher was still prime minister, Rushdie’s imagination got him into rare trouble when he published the allegedly “blasphemous” Satanic Verses. Whether the allegation of blasphemy was correct or not, is, by the way, irrelevant. That suggestion would not validate the non-publication of a book, and certainly would not justify the murder contract put out by the supreme leader of Iran, Ayatollah Khomeini, in February 1989.

Rushdie’s western critics then often couched their criticisms in terms that emphasised their empathy with the “Muslim anger” which gave rise to protests across the world and eventually the Ayatollah’s incitement to murder; they understood, they implied. They too, had been hurt. Mrs Thatcher herself (characterised as “Mrs Torture” in the book) said: “We have known in our religion people doing things which are deeply offensive to some of us and we have felt it very much.”

The Archbishop of Canterbury, Robert Runcie, commented: “I well understand the devout Muslims’ reaction, wounded by what they hold most dear and would themselves die for.”

No mention of being able to well understand or even imagine what it might be like to be on the end of protests, to see your effigy burned in anger across the world.

In his speech at the British Library, Rushdie described one of the worst aspects of the onslaught against his imaginative work; the need to counteract the ignorant prescriptions of The Satanic Verses by those who wanted to have him censored and worse.

“Once the attack was fully underway,” said Rusdhie, “I felt obliged for a long time to fight back against the creation of that false version of The Satanic Verses by offering counter-explanations of my own. I loathed doing it, and often felt that by offering the almost line by line defence that seemed necessary I was damaging the kind of open, private reading of my novel for which, like every writer, I had hoped.”

After Rushdie spoke, a remarkable speech from International Writer of Courage winner Mazen Darwish was read out. Darwish, founder of the Syrian Centre for Media and Freedom of Expression, is currently in a regime jail in Damascus, faced with charges of “publicicing terrorism”. He somehow managed to smuggle a letter to London.

Addressing Rushdie directly, he offered a startling apology for the inaction of many people in the Middle East at the time of the fatwa, saying their indifference was tantamount to collusion to murder.

Drawing a line between the censorship of 1989 and the rise of the Islamic State in Syria today, Darwish lamented: “What a shame this much blood has had to be spilled for us to realise, finally, that we are digging our own graves when we allow thought to be crushed by accusations of unbelief, calling people infidels, and when we allow opinion to be countered with violence.”

Not, bear in mind, the extrapolations of a north London liberal, but a man in prison who knows acutely the price of standing up for the individual, for empathy, and for free expression. Words to bear in mind the next time we’re tempted to embark on a collective outrage against words and thoughts and imagination itself.

This article was posted on 16 October 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

16 Apr 2013 | Newswire

David Fowler / Shutterstock.com

There are some fears that the funeral procession of Margaret Thatcher tomorrow could turn into a debacle of protest and arrest.

The Observer reported on Sunday that Commander Christine Jones, the police officer who will be in charge on the day, “warned” that police officers will have the power to arrest protesters under Section 5 of the Public Order Act on the day.

This isn’t exactly unusual; after all, the police always have the law at their disposal.

But it’s worth noting how problematic Section 5 of the Public Order Act can be, particularly in situations like tomorrow’s.

The section makes it an offence to engage in language (including writing on a placard) or behaviour “within the hearing or sight of a person likely to be caused harassment, alarm or distress thereby”.

This has led to problems for free speech and free protest in the past, from the arrest of Christian preachers to the conviction of Al Muhajiroun poppy-burner Emdadur Choudhury.

Considering the mix of Thatcher fans, tourists and events junkies who will line the route of the funeral cortege tomorrow along with the expected protesters, it is conceivable that any protest could be construed as likely to cause “harassment, alarm or distress” to someone. The issue is whether that likelihood alone enough to cause the police to intervene? Or should the deployment of the Public Order Act be limited to times when there are genuine threats to public order?

Tomorrow’s funeral, while not a “state funeral” as such, is most certainly a public event.

And being a public event, it will be open to protest: the police officers on duty tomorrow will need to bear in mind that they have a duty not just to safeguard the funeral proceedings, but to safeguard free expression too.

Padraig Reidy is senior writer at Index on Censorship. @mePadraigReidy

16 Apr 2013 | Uncategorized

David Fowler / Shutterstock.com

There are some fears that the funeral procession of Margaret Thatcher tomorrow could turn into a debacle of protest and arrest.

The Observer reported on Sunday that Commander Christine Jones, the police officer who will be in charge on the day, “warned” that police officers will have the power to arrest protesters under Section 5 of the Public Order Act on the day.

This isn’t exactly unusual; after all, the police always have the law at their disposal.

But it’s worth noting how problematic Section 5 of the Public Order Act can be, particularly in situations like tomorrow’s.

The section makes it an offence to engage in language (including writing on a placard) or behaviour “within the hearing or sight of a person likely to be caused harassment, alarm or distress thereby”.

This has led to problems for free speech and free protest in the past, from the arrest of Christian preachers to the conviction of Al Muhajiroun poppy-burner Emdadur Choudhury.

Considering the mix of Thatcher fans, tourists and events junkies who will line the route of the funeral cortege tomorrow along with the expected protesters, it is conceivable that any protest could be construed as likely to cause “harassment, alarm or distress” to someone. The issue is whether that likelihood alone enough to cause the police to intervene? Or should the deployment of the Public Order Act be limited to times when there are genuine threats to public order?

Tomorrow’s funeral, while not a “state funeral” as such, is most certainly a public event.

And being a public event, it will be open to protest: the police officers on duty tomorrow will need to bear in mind that they have a duty not just to safeguard the funeral proceedings, but to safeguard free expression too.

Padraig Reidy is senior writer at Index on Censorship. @mePadraigReidy