12 Jan 2018 | Journalism Toolbox Russian

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Титулованный кинодокументалист Марко Салюстро описывает журналистские проблемы освещения бедственного положения тысяч мигрантов, которые cбежали из стран «Черной Африки» и в настоящее время пребывают в Ливии “][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]

Ливийцы пытающиеся сбежать из страны на резиновой лодке в открытом море, Северо-запад от Триполя, Irish Defence Forces/Flickr

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

«ПОЧЕМУ, ЕСЛИ ОНИ знают, что могут умереть в море, они все же приезжают?» Это вопрос, который задают многие европейцы, о продолжающемся потоке мигрантов, пытающихся перебраться из Африки в Италию, Грецию и другие части Европы в переполненных, зачастую непригодных для мореплаванья лодках, и многие из которых при этом гибнут.

Я хотел показать, что происходит на другой стороне Средиземного моря – в Ливии.

Работать в Ливии сложно и опасно, даже с хорошим знанием страны и хорошими связями. Мы не знаем, чего ожидать.

Мы обнаружили сотни людей, которые находятся в лагерях, ожидая и надеясь на лучшую жизнь. Некоторые были настолько истощавшими, что на их спинах торчали кости. Одна женщина сказала нам: «Что будет дальше, мы не знаем».

Мигранты очень хотят говорить на камеру, отчаянно пытаясь обратиться за помощью, и сказать: «Мы здесь, и мы люди, мы существуем». В некотором роде они верят, что если бы только внешний мир мог узнать, что-то могло бы измениться. Они не могут поверить, что они просто оставлены на произвол судьбы.

Эти отчаявшиеся эмигранты, которые бежали от террора в своей стране (Судан, Эритрея и Сомали), содержатся в огромных ангарах. Они вынуждены жить там, обычно с небольшим количеством воды или пищи, и рискуя быть избитыми. Находясь на полпути между домом и свободой, которую они ищут, они не знают, уедут ли они когда-нибудь из Ливии.

В рамках исследования для этой статьи мне был необходим доступ к правительственным центрам и допуск министерства внутренних дел. Это часто требует разрешений, выданных полицией или другими органами, и подразумевает множество дней, проведенных в залах ожидания, и телефонных звонков в разные офисы. Иногда даже такой подготовки было недостаточно. Например, когда я посещал официально контролируемый правительством центр Абу-Слим, несмотря на то, что встреча была организованна министерством и несмотря на сопровождающего меня офицера, ополченцы, которых заранее не предупредили, заблокировали наш визит. Когда мы вошли через ворота, несколько молодых ребят в шлепанцах и с пистолетами начали угрожать руководителю и офицерам.

Конечно, поскольку свободы слова в Ливии попросту нет, мы просто царапаем поверхность и пытаемся добраться как можно глубже, учитывая, что то, что мы видим, это далеко не полная картина. Во время моей работы все ополченцы, с которыми я встречался, стремились показать, насколько хорошо они контролируют мигрантов и, что удивительно, они вообще не пытались скрыть, как жестоко они с ними обращаются. В некотором роде, они, казалось, были уверены, что в Европе никого это не волнует, пока они в силах воспрепятствовать прибытию мигрантов на наши берега. Иногда единственной причиной, почему мне разрешали работать в лагере, было то, что ополчение полагало, что освещение в СМИ могло бы оказаться полезным для давления на правительство.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Самое страшное состоит в том, что мы видели и документировали хорошую сторону: то, что показано, считается приемлемым или даже чем-то, чем можно гордиться. Несмотря на это, условия жизни, которые я видел, были действительно суровые и насилие является частью повседневности. То, что происходит вне поля зрения, может быть даже более ужасающим.

Общественное мнение европейцев было потрясено, когда 18 апреля 2015 года более 800 мужчин, женщин и детей утонули в Средиземном море. После этого Европейский Союз выразил готовность бомбить лодки и порты, используемые для контрабанды мигрантов через море. Правительство Триполи, поддерживаемое исламистской коалицией «Рассвет Ливии», объявило намерение участвовать в борьбе против незаконной переправки людей и начало кампанию с целью показать серьезную борьбу с потоком мигрантов. Ливийское правительство также получает поддержку от ЕС, чтобы помочь контролировать переправы в Средиземноморье.

Мигранты стали ценным товаром в борьбе за власть, поскольку ливийские ополченцы, которые, как считается, играют важную роль в переправке людей, шагнули в миграционную политику, чтобы попытаться получить влияние на правительство.

Правительственные чиновники рассказали мне, что они не имеют достаточных ресурсов для выполнения, какого-либо объявленного правительством мероприятия, поэтому они наняли жестоких ополченцев «чтобы защитить берега и прекратить незаконное вторжение в Европу».

Истории мигрантов ужасны, они не вольны свободно говорить и то, что мы можем услышать от них – не вся реальность. Мигранты, с которыми я встретился снова, когда некоторым из них удалось добраться до Европы, рассказывали мне о пытках и убийствах как о повседневной рутине.

Я думал, что важно рассказать о том, что происходит, но пребывает за пределами видимости европейцев. Хотя общественность требовала больших усилий, чтобы спасти жизни мигрантов в Средиземном море, действия, предпринятые правительством Триполи для проявления себя как надежного партнера ЕС в контроле над миграционным потоком, ухудшали условия жизни и увеличивали опасность для мигрантов в Ливии.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Марко Салюстро, автор специального выпуска «Вайс Ньюс» «Европа или смерть: торговля мигрантами в Ливии» и победитель премии имени Рори Пека 2016 года

Статья впервые напечатана в выпуске журнала Индекс на Цензуру (весна 2017)

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Fashion Rules” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F12%2Fwhat-price-protest%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The winter 2016 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at fashion and how people both express freedom through what they wear.

In the issue: interviews with Lily Cole, Paulo Scott and Daphne Selfe, articles by novelists Linda Grant and Maggie Alderson plus Eliza Vitri Handayani on why punks are persecuted in Indonesia.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”82377″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/12/what-price-protest/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

12 Jan 2018 | Journalism Toolbox Spanish

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”El galardonado cineasta Marco Salustro describe los desafíos periodísticos que supone documentar la difícil situación de los miles de migrantes huidos de África subsahariana, ahora retenidos en Libia”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]

Varios libios intentan huir del país por mar en una embarcación de goma al noroeste de Trípoli, Irish Defence Forces/Flickr

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

«¿Por qué, si saben que podrían morir en el mar, siguen viniendo?». Esa es la pregunta que se hacen muchos europeos sobre la constante marea de migrantes que intentan cruzar de África a Italia, Grecia y otras partes de Europa, hacinados en barcas a menudo no aptas para navegar, muchos de ellos muriendo en el intento.

Quise mostrar lo que está pasando al otro lado del Mediterráneo, en Libia. Trabajar en el país es difícil y peligroso, incluso aunque conozcas el lugar y tengas buenos contactos. No sabíamos qué esperar.

Lo que descubrimos fueron cientos de personas retenidas en campos, esperando, soñando con una vida mejor. Algunos estaban tan delgados que se les veían los huesos de la espalda. «No sabemos qué viene después», nos dijo una mujer.

Los migrantes se muestran ansiosos por hablar a la cámara, desesperados por pedir auxilio, por decir: «Estamos aquí y somos humanos, existimos». En cierto modo creen que, si el mundo ahí fuera lo supiese, pasaría algo y cambiarían las cosas. No se pueden creer que estén abandonados a su suerte.

Estos refugiados, personas desesperadas que huyen del terror en su propio país (Sudán, Eritrea y Somalia), están alojados en hangares gigantes. Los obligan a vivir allí, a menudo con comida y agua escasas, y corren el riesgo de sufrir palizas. Habitantes de una zona a medio camino entre su tierra natal y la libertad que ansían, no tienen ni la más remota idea de si podrán dejar Libia algún día.

Durante mi investigación sobre el tema, necesité acceder a centros controlados por el gobierno y obtener el permiso del ministerio del interior. Un requisito habitual son las autorizaciones firmadas por la policía u otros cuerpos, cosa que supone pasar días enteros en salas de espera y hacer múltiples llamadas a diversas oficinas. A veces ni siquiera esos preparativos bastaban, como cuando en una ocasión visité el centro Abu Slim, oficialmente controlado por el gobierno. Aunque la visita la había organizado el ministerio e iba acompañado por un agente, los milicianos, a quienes no habían consultado con antelación, nos vetaron la ventrada. Al cruzar las puertas, un grupo de jóvenes en sandalias y armados con pistolas amenazaron al director y a los agentes.

Por supuesto, al no haber libertad de prensa en Libia, apenas rascamos la superficie y tratamos de ahondar tanto como sea posible, teniendo en cuenta que lo que vemos nunca es toda la realidad.

Mientras trabajaba, todas las milicias con las que me encontré demostraban de buena gana lo bien que se les daba controlar a los migrantes, y lo más increíble de todo es que no se preocupaban por ocultar todos los abusos que perpetraban. En cierto modo parecían creer que en Europa nada de esto nos importa, mientras sigan encargándose de que no lleguen migrantes a nuestras costas. En algunos casos, la única razón por la que me permitían trabajar en un campo era porque la milicia creía que la visibilidad de los medios podría servir para presionar al gobierno.

Lo más aterrador de todo es que lo que veíamos y documentábamos era solo la mejor parte: lo que enseñan lo consideran aceptable, incluso una fuente de orgullo. Aun así, las condiciones de vida que presencié eran extremas y los abusos estaban a la orden del día. Es posible que lo que pasa cuando nadie mira sea aún más horrible.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

La muerte de más de 800 hombres, mujeres y niños ahogados en el Mediterráneo el 18 de abril de 2015 conmovió la opinión pública europea. Después de aquello, la Unión Europea declaró estar dispuesta a bombardear los barcos y puertos involucrados en el transporte de migrantes por mar. El gobierno de Trípoli, que cuenta con el apoyo de la coalición islamista Amanecer Libio, declaró su intención de intervenir en la lucha contra el tráfico de personas, e inició una campaña con la intención de demostrar que no se andaba con chiquitas a la hora de contener la llegada de migrantes. El gobierno libio también recibe apoyo de la UE a cambio de ayudar a controlar el tráfico en el Mediterráneo.

Los migrantes se han convertido en una valiosa moneda de cambio en la pugna por el poder, pues las milicias libias —de las que se cree que cumplen un papel fundamental en el mercado del tráfico de personas— se metieron en política de migración para tratar de ejercer más influencia sobre el gobierno.

Varios funcionarios del estado me contaron que no tenían los recursos suficientes para llevar a cabo ninguna de las operaciones anunciadas por el gobierno, así que habían contratado la fuerza bruta de las milicias «para asegurar las costas y evitar que se cruce ilegalmente hasta Europa».

Las historias que cuentan los migrantes son espantosas, no pueden hablar con libertad y lo que nos llega de ellos no es toda la verdad. Los migrantes con los que volví a encontrarme, cuando algunos de ellos lograron llegar a Europa, me hablaron de torturas y matanzas como parte de la rutina diaria.

Me pareció importante contar esta historia para revelar lo que ocurre más allá de donde alcanza la vista de los europeos. Mientras el público exigía un mayor esfuerzo por salvar las vidas de los migrantes en el mar Mediterráneo, los intentos del gobierno de Trípoli por mostrarse como un colaborador de confianza en las actividades de control de la migración de la UE no han hecho más que empeorar las condiciones de vida y multiplicar los peligros que sufren los migrantes en Libia.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Marco Salustro produjo el especial Europe or Die, Libia’s Migrant Trade para VICE news y es ganador del premio Rory Peck 2016 al mejor reportaje

Este artículo fue publicado en la revista de Index on Censorship en invierno de 2016

Traducción de Arrate Hidalgo

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Fashion Rules” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F12%2Fwhat-price-protest%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The winter 2016 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at fashion and how people both express freedom through what they wear.

In the issue: interviews with Lily Cole, Paulo Scott and Daphne Selfe, articles by novelists Linda Grant and Maggie Alderson plus Eliza Vitri Handayani on why punks are persecuted in Indonesia.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”82377″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/12/what-price-protest/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

12 Jan 2018 | Journalism Toolbox Arabic

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”يصف المخرج المخضرم ماركو سالوسترو التحديّات الصحفية عند تغطية محنة الآلاف من المهاجرين من أفريقيا جنوب الصحراء الكبرى والمحتجزين حاليا في ليبيا”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]

ليبيون يحاولون الهرب من البلاد على متن قارب مطّاطي في المياه شمال غرب العاصمة طرابلس, Irish Defence Forces/Flickr

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

“إذا كانوا يعلمون بأنهم قد يموتون في عرض البحر، فلماذا يستمرّون بالقدوم هنا؟” هذا السؤال يطرحه العديد من الأوروبيين حول استمرار تدفّق المهاجرين الذين يحاولون العبور من أفريقيا إلى إيطاليا واليونان وأجزاء أخرى من أوروبا على متن قوارب مزدحمة وأحيانا غير صالحة للإبحار، حيث يفقد كثير منهم حياتهم قبل الوصول.

أردّتُ إظهار ما يحدث على الجانب الآخر من البحر الأبيض المتوسط، وتحديدا في ليبيا. لكن العمل في ليبيا صعب ومحفوف بالخطر، حتى لو كان لدى الصحفي معرفة واسعة بالبلاد وصلات جيدة. فنحن لم نكن نعرف ما يجب علينا أن نتوقعه. اكتشفنا أنه يوجد هناك مئات من الأشخاص المحتجزين في المخيمات، وهم ينتظرون ويأملون في حياة أفضل. البعض منهم كان نحيلا لدرجة أن عظامهم كانت بارزة من تحت جلودهم. “نحن لا نعلم ماذا سوف يحدث لنا الآن”، تتحسّر إحدى النساء هناك.

أبدى هؤلاء المهاجرون رغبة كبيرة في التحدث أمام الكاميرا، رمبا في محاولة يائسة لطلب المساعدة، وليقولوا: “نحن هنا…نحن بشر، ونحن موجودون”. كانوا يعتقدون بأنه ربما إذا علم العالم الخارجي عن محنتهم، فقد يحدث شيء ما ليغيّر أوضاعهم. هم لا يصدّقون أن العالم تركهم ليواجهوا مصيرهم هكذا.

يقيم هؤلاء اللاجئون اليائسون الذين يهربون من الاضطرابات في بلادهم (السودان وإريتريا والصومال) في حظائر ضخمة، حيث هم مجبرون على العيش ولا يحصلون في معظم الأحيان الّا على كميات قليلة من الماء والغذاء، كما أنّهم يتعرّضون للضرب. هنا، في منتصف الطريق بين بلادهم وبين الحرية التي يسعون للوصول اليها، ليس لديهم أيّ فكرة ما إذا كانوا سيغادرون ليبيا أبدا.

خلال قيامي بجمع المعلومات من أجل هذا التقرير، كان يتعيّن عليّ الحصول على إذن من وزارة الداخلية لزيارة المراكز التي تديرها الحكومة. وكثيرا ما كان ذلك يتطلب تصاريح موقعة من الشرطة أو هيئات الأخرى، حيث قد يقضي المرء أيّاما بأكملها في غرف الانتظار ويضطر الى اجراء مكالمات هاتفية متعددة إلى مختلف الجهات. ولكن في بعض الأحيان، حتى ذلك القدر من التحضيرات لم يكن كافيا، ففي أحد المرّات خلال زيارتنا الى مركز أبو سليم الذي تسيطر عليه الحكومة بشكل رسمي، وعلى الرغم من أن الزيارة كان قد تم ترتيبها مسبقا من قبل الوزارة التي أرسلت ضابطا برفقتي الى المخيّم، منعنا رجال الميليشيات الذين لم يتم قد تم استشارتهم مسبقا من الدخول. عند عبورنا البوابة رأينا عددا من الشبّان يرتدون الشبشب ويحملون المسدسات يهدّدون المدير والضبّاط هناك.

بطبيعة الحال، وبما أنه لا توجد هناك حرية صحافة في ليبيا، فإن جلّ ما يمكننا فعله هو الحفر قليلا تحت السطح ومحاولة النزول الى العمق بأكبر قدر ممكن، مع الأخذ في الاعتبار أن ما

نراه لا يمكن أن يكون هو الواقع بكامل صورته.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

خلال عملي، كانت جميع الميليشيات التي التقيت بها حريصة على التباهي بقدرتها على السيطرة على المهاجرين، ومما يثير الدهشة، فأنهم لم يكونوا مهتمين على الإطلاق بإخفاء الاعتداءات التي يرتكبونها ضدهم. وبدا كأنّهم يعتقدون أن لا أحدا في أوروبا يكترث بذلك، طالما أنّهم يقومون بمنع المهاجرين من الوصول الى شواطئهم. في بعض الحالات، كان السبب الوحيد الذي سمح لي من أجله بالعمل في أحد المخيمات هو أن الميليشيات اعتقدت أن التغطية الإعلامية قد تكون مفيدة للضغط على الحكومة.

ولكن أخطر شيء هو أن ما كنا نراه ونقوم بتوثيقه كان الجانب الجيّد، أي أن ما تم السماح لنا برؤيته كان يعتبر مقبولا أو حتى شيء يفتخر به، ولكن على الرغم من ذلك، كانت الظروف المعيشية التي رأيتها قاسية حقا والانتهاكات مجرّد جزءا من الحياة الطبيعية في المخيّمات. ما يحدث بعيدا عن الأنظار قد يكون أكثر فظاعة بكثير.

صدم الرأي العام الأوروبي عندما غرق أكثر من 800 رجل وامرأة وطفل في المتوسط في 18 نيسان / أبريل 2015. وعقب ذلك، أعرب الاتحاد الأوروبي عن استعداده لقصف القوارب والموانئ المستخدمة لتهريب المهاجرين عبر البحر. وأعلنت حكومة طرابلس، المدعومة من قبل تحالف فجر ليبيا الإسلامي، عزمها على المشاركة في الكفاح ضد تهريب البشر، وبدأت حملة تهدف إلى إظهار جديتها بشأن كبح تدفّق المهاجرين. كما تتلقى الحكومة الليبية الدعم من الاتحاد الأوروبي للمساعدة في مراقبة الهجرة عبر البحر الأبيض المتوسط.

لقد أصبح المهاجرون سلعة قيّمة في إطار المعركة لأجل السلطة حيث قامت الميليشيات الليبية، التي يُعتقد على نطاق واسع بأنها متوّرطة بشكل كبير في تهريب البشر، بالتدّخل في مسألة الهجرة لاكتساب النفوذ والتأثير على الحكومة.

وقال لي مسؤولو الحكومة إنهم ليس لديهم ما يكفي من الموارد لتنفيذ أي من الاجراءات التي أعلنتها الحكومة لذا اضطروا الى التعامل مع الميليشيات العنيفة “لتأمين الشواطئ ووقف العبور غير الشرعي إلى أوروبا”.

قصص المهاجرين مروّعة، وهم لا يستطيعون التحدّث بحرية. وما نستطيع أن نسمعه منهم لا يعكس الواقع بكامله. بعض المهاجرين الذين التقيت بھم مجدّدا عندما وصلوا إلی أوروبا أخبروني أن أعمال القتل والتعذيب كانت جزءا من روتينهم الیومي.

اعتقدت أنه من المهم تغطية هذه القصة لإظهار ما يحدث بعيدا عن مرأى الشعب الأوروبي. فبينما كان الرأي العام يطالب ببذل جهد أكبر لإنقاذ حياة المهاجرين في البحر الأبيض المتوسط، كانت الإجراءات التي اتخذتها حكومة طرابلس لإظهار نفسها كشريك موثوق به للاتحاد الأوروبي في السيطرة على تدفّق المهاجرين تفاقم من معاناة المهاجرين في ليبيا وتضعهم في خطر أكبر.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

ماركو سالوسترو هو مخرج وثائقي “أوروبا أو الموت” لصالح فايس نيوز، وحائز على جائزة روري بيك للصحافة في عام ٢٠١٦.

ظهر هذا المقال أولا في مجلّة “اندكس أون سنسورشيب” بتاريخ ١٩ يناير/كانون الثاني 2017

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Fashion Rules” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F12%2Fwhat-price-protest%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The winter 2016 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at fashion and how people both express freedom through what they wear.

In the issue: interviews with Lily Cole, Paulo Scott and Daphne Selfe, articles by novelists Linda Grant and Maggie Alderson plus Eliza Vitri Handayani on why punks are persecuted in Indonesia.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”82377″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/12/what-price-protest/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

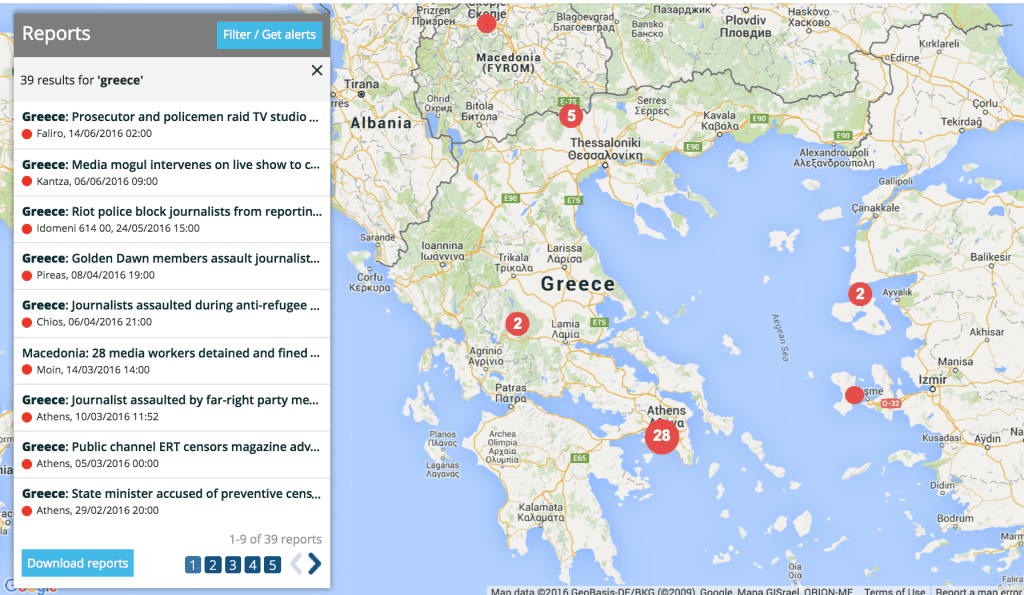

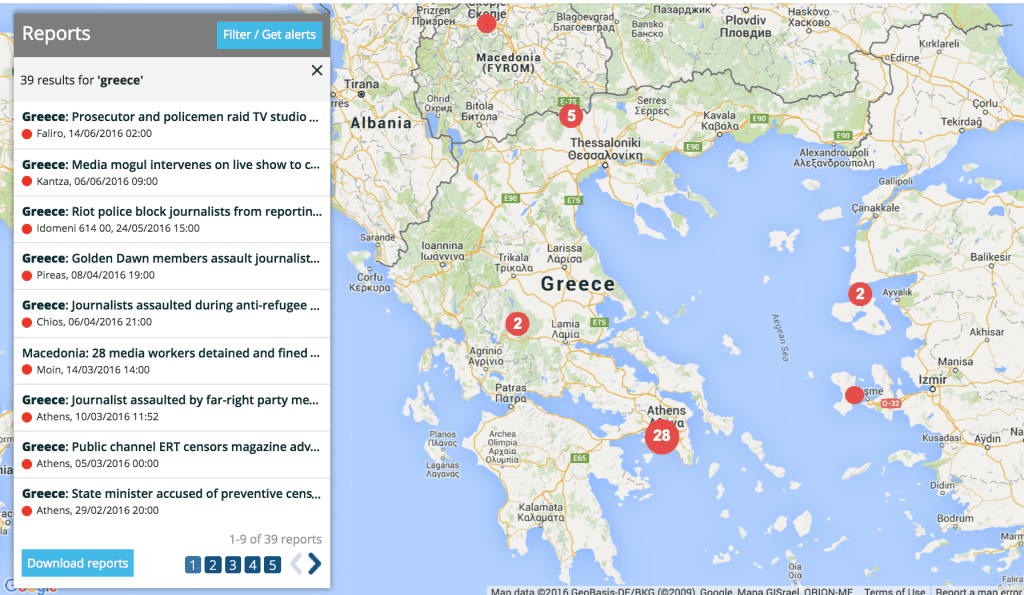

19 Jul 2016 | Europe and Central Asia, Greece, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features

As Greece tries to deal with around 50,000 stranded refugees on its soil after Austria and the western Balkan countries closed their borders, attention has turned to the living conditions inside the refugee camps. Throughout the crisis, the Greek and international press has faced major difficulties in covering the crisis.

“It’s clear that the government does not want the press to be present when a policeman assaults migrants,” Marios Lolos, press photographer and head of the Union of Press Photographers of Greece said in an interview with Index on Censorship. “When the police are forced to suppress a revolt of the migrants, they don’t want us to be there and take pictures.”

Last summer, Greece had just emerged from a long and painful period of negotiations with its international creditors only to end up with a third bailout programme against the backdrop of closed banks and steep indebtedness. At the same time, hundreds of refugees were arriving every day to the Greek islands such as Chios, Kos and Lesvos. It was around this time that the EU’s executive body, the European Commission, started putting pressure on Greece to build appropriate refugee centres and prevent this massive influx from heading to the more prosperous northern countries.

It took some months, several EU Summits, threats to kick Greece out of the EU free movement zone, the abrupt closure of the internal borders and a controversial agreement between the EU and Turkey to finally stem migrant influx to Greek islands. The Greek authorities are now struggling to act on their commitments to their EU partners and at the same time protect themselves from negative coverage.

Although there were some incidents of press limitations during the first phase of the crisis in the islands, Lolos says that the most egregious curbs on the press occurred while the Greek authorities were evacuating the military area of Idomeni, on the border with Macedonia.

In May 2016, the Greek police launched a major operation to evict more than 8,000 refugees and migrants bottlenecked at a makeshift Idomeni camp since the closure of the borders. The police blocked the press from covering the operation.

“Only the photographer of the state-owned press agency ANA and the TV crew of the public TV channel ERT were allowed to be there,” Lolos said, while the Union’s official statement denounced “the flagrant violation of the freedom and pluralism of press in the name of the safety of photojournalists”.

“The authorities said that they blocked us for our safety but it is clear that this was just an excuse,” Lolos explained.

In early December 2015, during another police operation to remove migrants protesting against the closed borders from railway tracks, two photographers and two reporters were detained and prevented from doing their jobs, even after showing their press IDs, Lolos said.

While the refugees were warmly received by the majority of the Greek people, some anti-refugee sentiment was evident, giving Greece’s neo-nazi, far-right Golden Dawn party an opportunity to mobilise, including against journalists and photographers covering pro- and anti-refugee demonstrations.

On the 8 April 2016, Vice photographer Alexia Tsagari and a TV crew from the Greek channel E TV were attacked by members of Golden Dawn while covering an anti-refugee demonstration in Piraeus. According to press reports, after the anti-refugee group was encouraged by Golden Dawn MP Ilias Kasidiaris to attack anti-fascists, a man dressed in black, who had separated from Golden Dawn’s ranks, slapped and kicked Tsagari in the face.

“Since then I have this fear that I cannot do my work freely,” Tsagari told Index on Censorship, adding that this feeling of insecurity becomes even more intense, considering that the Greek riot police were nearby when the attack happened but did not intervene.

Following the EU-Turkey agreement in late March which stemmed the migrant flows, the Greek government agreed to send migrants, including asylum seekers, back to Turkey, recognising it as “safe third country”. As a result, despite the government’s initial disapproval, most of the first reception facilities have turned into overcrowded closed refugee centres.

“Now we need to focus on the living conditions of asylum seekers and migrants inside the state-owned facilities. However, the access is limited for the press. There is a general restriction of access unless you have a written permission from the ministry,” Lolos said, adding that the daily living conditions in some centres are disgraceful.

Ola Aljari is a journalist and refugee from Syria who fled to Germany and now works for Mapping Media Freedom partners the European Centre for Press and Media Freedom. She visited Greece twice to cover refugee stories and confirms that restrictions on journalists are increasing.

“With all the restrictions I feel like the authorities have something to hide,” Aljari told Index on Censorship, also mentioning that some Greek journalists have used bribes in order to get authorisation.

Greek journalist, Nikolas Leontopoulos, working along with a mission of foreign journalists from a major international media outlet to the closed centre of VIAL in Chios experienced recently this “reluctance” from Greek authorities to let the press in.

“Although the ministry for migration had sent an email to the VIAL director granting permission to visit and report inside VIAL, the director at first denied the existence of the email and later on did everything in his power to put obstacles and cancel our access to the hotspot,” Leontopoulos told Index on Censorship, commenting that his behaviour is “indicative” of the authorities’ way of dealing with the press.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]