29 Feb 2012 | Awards

Recognising artists, filmmakers and writers whose work asserts artistic freedom and battles against repression and injustice

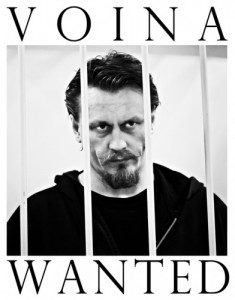

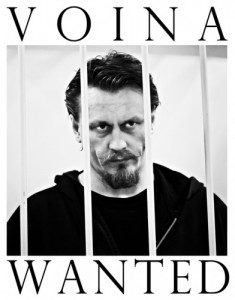

Voina, performance artists, Russia

Voina, meaning “War”, is a collective of radical Russian anarchist artists who combine political protest and performance art.

Voina, meaning “War”, is a collective of radical Russian anarchist artists who combine political protest and performance art.

Voina’s carries out actions directed against the authorities. In June 2010, members painted a 65-metre phallus on a drawbridge in St Petersburg which, when raised, faced the city headquarters of the federal security service.

Voina members Vorotnikov and Leonid Nikolayev were imprisoned from November 2010 to February 2011 in connection with an anti-corruption protest and, in July 2011, Russian police issued an international arrest warrant for Vorotnikov. A warrant for the arrest of fellow artist Natalia Sokol was issued in December 2011.

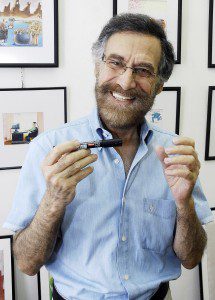

Ai Weiwei, artist, China

AiWeiwei is a Chinese artist and activist whose work incorporates social and political activism. He has investigated corruption and cover-ups and openly criticised the Chinese government’s record on human rights.

AiWeiwei is a Chinese artist and activist whose work incorporates social and political activism. He has investigated corruption and cover-ups and openly criticised the Chinese government’s record on human rights.

Ai’s 81-day detention in 2011 caused international uproar. He was arrested in April, alongside several of his friends and colleagues. Since the Chinese authorities released him on bail in June 2011, he has been fined $2.4 million in back taxes and penalties. Though officials arrested Ai for alleged economic crimes, supporters say he was punished for his activism and vocal critiques of the government. He paid a $1.3 million bond with loans from supporters, who contributed online and in person and even throwing cash over the walls of his studio in Beijing.

In November 2011, after Ai announced that authorities were investigating his cameraman for pornography in connection with photos that featured the artist and four women naked, internet users responded tweeting nude photos of themselves in support.

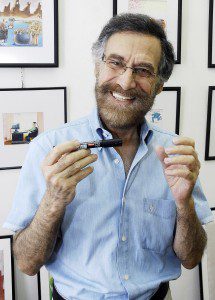

Ali Ferzat, cartoonist, Syria

Syrian cartoonist Ali Ferzat has been called “an icon of freedom in the Arab world”. He has spent decades ridiculing dictators in more than 15,000 caricatures. His depictions of President Assad and the police state have helped galvanise revolt in Syria.

Syrian cartoonist Ali Ferzat has been called “an icon of freedom in the Arab world”. He has spent decades ridiculing dictators in more than 15,000 caricatures. His depictions of President Assad and the police state have helped galvanise revolt in Syria.

In August 2011, Ferzat was wrenched from his vehicle in central Damascus by pro-Assad masked gunmen who beat him badly and broke his hands. Passers-by found Ferzat dumped at the side of a road; his briefcase and the drawings inside it had been confiscated by his attackers.

Ferzat earned regional and international recognition in the 1980s with stinging cartoons of officials, autocrats and dictators including Saddam Hussein and Muammar Gaddafi. Saddam Hussein called for Ferzat’s death in 1989 after an unfavourable portrait of him was exhibited in Paris and Ferzat’s cartoons have been banned in numerous Arabic countries.

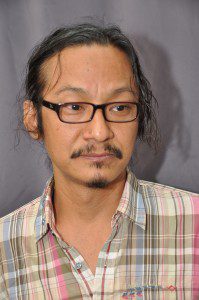

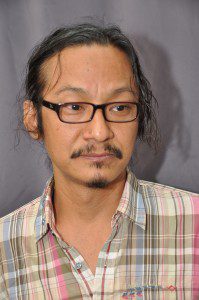

Min Htin Ko Ko Gyi, poet, Burma

Min Htin Ko Ko Gyi, a poet, filmmaker and screenwriter, co-founded Burma’s inaugural Arts of Freedom Film Festival, which took place in early January 2012.

Min Htin Ko Ko Gyi, a poet, filmmaker and screenwriter, co-founded Burma’s inaugural Arts of Freedom Film Festival, which took place in early January 2012.

Burmese citizens were invited to create a short film on the theme of freedom. Despite the state media’s refusal to cover the announcement, Ko Ko Gyi and his organisers received 188 submissions. Thousands gathered in Rangoon under the banner “Free Art, free thought, freedom”, to watch the selected films. More than 7,000 attendees voted for Cut This Scene to win one of five awards. The film is a satire of a government censorship committee struggling to set the criteria by which to censor films.

1 Jan 2012 | Asia and Pacific

Burma’s democracy movement leader Aung San Suu Kyi, film director Min Htin Ko Ko Gyi, and former political prisoner and comedian Maung Thura aka Zarganar are pushing the boundaries of prevalent state censorship in the Arts of Freedom Film Festival in Rangoon, which began on 31 December will continue to 4 Jan.

In a bid to open the gates on artistic expression, Burmese citizens regardless of age, qualifications and location were invited to submit a short film on the theme of “freedom.” More than 180 films were submitted, despite the refusal of state-owned newspapers to carry the announcement, according to Min Htin Ko Ko Gyi, a poet and filmmaker and one of the organisers of the festival. The comedian Zarganar, who was released from prison in October is also another organiser of the festival, which is also sponsored by the well-known Burmese democracy campaigner Aung San Suu Kyi. All three will be a part of the panel of judges.

Min Htin Ko Ko Gyi told Index that “it is the first time” for a festival with the theme of freedom to take place in Burma. He said that the organisers “did not ask for permission from the authority,” but they are using the festival to test “the limit of the state,” because they “want to know how much freedom will the state allow.”

Under the country’s Television and Video Act 1996, all videos, with the expection of family recordings, must go through the Video Censor Board before distribution and screening for the public. Failure to comply may result in fines, imprisonment of up to three years and confiscation of property. The law stipulates that members of the Board shall consist of two representatives from the Myanmar Motion Pictures Enterprise, a number of representatives from government’s organizations and “suitable citizens”. The Information Ministry has the sole authority to form, appoint and dismiss member(s) of the Board.

In early December, Minister of Information and Culture and former army general Kyaw Hsan reportedly said in a meeting with executives of the Myanmar Motion Picture Organization, the Board and professionals of movie industry that the censorship regime for press and motion pictures will be gradually relaxed. He also announced plans to allow the Chinese film industry and other international players to invest in the country’s movie sector. The move is yet another in a series of changes by the military-backed government in 2011 to move towards democratisation, and the United States and European Union have responded with cautious optimism.

However, despite claims of relaxed censorship laws, the Board reportedly seized some submissions sent via post from overseas. Organisers also faced challenges downloading overseas entries submitted online due to slow internet service in Burma. Still, the films have been well received and one of the short films has become a viral hit on YouTube and Vimeo. The 18-minute short entitled, “Ban that Scene!” is film director Htun Zaw Win’s humorous look at the country’s video censors.

Htun Zaw Win, aka Wyne brought together veteran actors to play censors preoccupied with protecting their positions. He critiques the gluttonous and corrupt officials with scenes showing them ordering meals from high-scale restaurants before a vetting session, at the expense of filmmakers. In another scene, the censors brawl over disagreements about which scenes should be cut from the film during a screening, and eventually decide to cut all disputed scenes. The lone censor who favoured the film was intimidated and drowned out by the disagreements of his colleagues.

“I tried to portray the state of censorship as realistically as possible in the most polite manner. What actually happens is much worse,” Wyne told Index. “The present tight censorship suffocates creativity in the movie industry.”

Wyne, who has been in the industry for 22 years, said on Radio Free Asia Burmese Service on 27 December that the government should not censor the film if it is serious about democratisation. He admitted was unsure of the consequences for making the film. “If our country is really democratising as the government said, then bad practices of the censorship system should be changed too.”

According to Min Htin Ko Ko Gyi the festival started with interviews with filmmakers on 31 December, screenings of selected submissions from 1 Jan onwards, and an award ceremony on the country’s Independence Day on 4 Jan. “We don’t know how the authority will react. But we just have to do it.”

Voina, meaning “War”, is a collective of radical Russian anarchist artists who combine political protest and performance art.

Voina, meaning “War”, is a collective of radical Russian anarchist artists who combine political protest and performance art. AiWeiwei is a Chinese artist and activist whose work incorporates social and political activism. He has investigated corruption and cover-ups and openly criticised the Chinese government’s record on human rights.

AiWeiwei is a Chinese artist and activist whose work incorporates social and political activism. He has investigated corruption and cover-ups and openly criticised the Chinese government’s record on human rights. Syrian cartoonist Ali Ferzat has been called “an icon of freedom in the Arab world”. He has spent decades ridiculing dictators in more than 15,000 caricatures. His depictions of President Assad and the police state have helped galvanise revolt in Syria.

Syrian cartoonist Ali Ferzat has been called “an icon of freedom in the Arab world”. He has spent decades ridiculing dictators in more than 15,000 caricatures. His depictions of President Assad and the police state have helped galvanise revolt in Syria. Min Htin Ko Ko Gyi, a poet, filmmaker and screenwriter, co-founded Burma’s inaugural Arts of Freedom Film Festival, which took place in early January 2012.

Min Htin Ko Ko Gyi, a poet, filmmaker and screenwriter, co-founded Burma’s inaugural Arts of Freedom Film Festival, which took place in early January 2012.