23 Aug 2013 | Comment, News and features, Religion and Culture

Richard Dawkins and ex-Muslim campaigner Maryam Namazie at a rally in support of free expression, London, February 2012. Image Demotix/Peter Marshall

This week has seen an outbreak of atheist infighting, as Observer and Spectator writer Nick Cohen launched an attack at writers such as the Independent’s Owen Jones and the Telegraph’s Tom Chivers. Their crime, apparently was to focus criticism on atheist superstar Richard Dawkins for his tweets, particularly those about Islam and Muslims, while not criticising religious fundamentalists.

Jones and Chivers have both replied, quite reasonably, to Cohen’s article.

Dawkins’s controversial tweets display a political naivety that can often be found in organised atheism and scepticism. Anyone who’s witnessed the ongoing row within that community over feminism will recognise a certain tendency to believe that science and facts alone are virtuous, and “ideologies” based on something other than empirical data just get in the way.

Hence the professor can tweet the statement “All the world’s Muslims have fewer Nobel Prizes than Trinity College, Cambridge” as if this in itself proves something, without further thinking about the political, historical, social and, indeed, geographical factors behind this apparent fact, and then be surprised when people object.

I’m not going to suggest that Dawkins be silenced. He can and will tweet what he wants. And it’s worth pointing out that those on the liberal left who have raised concerns about Dawkins’s pigeonholing of Muslims can be equally guilty of treating all adherents to a religion as a monolithic bloc: this happens mostly with Muslims, but often, at least in the UK with Roman Catholics as well, as if declaring the shahada or accepting the sacraments is akin to being assimilated into Star Trek’s Borg. Any amount of non-Muslim commentators who opposed the Iraq war, for example will tell you that “Muslims” care deeply about the Iraq war, neatly soliciting support for their arguments while also casting themselves as friends of a minority group. And for a great example of treating “Catholics” as a single entity, Johann Hari’s address ahead of the visit by former pope Benedict XVI to Britain in 2010, takes some beating:

I want to appeal to Britain’s Roman Catholics now, in the final days before Joseph Ratzinger’s state visit begins. I know that you are overwhelmingly decent people. You are opposed to covering up the rape of children. You are opposed to telling Africans that condoms “increase the problem” of HIV/Aids. You are opposed to labelling gay people “evil”. The vast majority of you, if you witnessed any of these acts, would be disgusted, and speak out. Yet over the next fortnight, many of you will nonetheless turn out to cheer for a Pope who has unrepentantly done all these things.

I believe you are much better people than this man. It is my conviction that if you impartially review the evidence of the suffering he has inflicted on your fellow Catholics, you will stand in solidarity with them – and join the [anti-Pope] protesters.”

Hari is literally telling people what they think. A bit like the Vatican tries to do.

Communalist rhetoric, whether used to attack or support certain groups, is the enemy of free speech, as it automatically discredits dissenting voices: “If you do not believe X, as I say members of group Y do, then you cannot be a true member of the group; ergo you can be ignored, or censored.”

Nowhere is this more evident than in India, where communalism, thanks to the British Empire, is enshrined in law. The 1860 penal code of India makes it illegal to “outrage religious feelings or any class by insulting its religion or religious beliefs”. This establishes, in an odd inversion of the United States’s model of secularism, a state where all religions are privileged, while those who criticise them are unprotected. And in India, that can be dangerous.

Sixty-seven-year-old Narendra Dabholkar was killed this week, shot dead on his morning walk.

Dabholkar was a rationalist activist, in a country where that means a little bit more than agreeing or disagreeing with Richard Dawkins. Dabholkar and his comrades such as Sanal Edamaruku have for years been engaged in a war against the superstition that leaves poor Indians open to exploitation from “holy men”. A large part of their work involves revealing the workings of the tricks of the magic men, like a deadly serious Penn and Teller. Edamaruku famously appeared on television in 2008, trying not to laugh as a guru attempted to prove that he can kill the rationalist with his mind. Dabholkar was agitating for a bill in that would curtail “magic” practitioners in Maharashtra state.

Edamaraku is now in exile, fleeing blasphemy charges and death threats that resulted after he debunked the “miracle” of a weeping statue at a Mumbai Catholic church. His friend is dead. Both victims of those who have most to gain from communalism: the con men and fundamentalists for whom the individual dissenting voice is a threat. Atheists, sceptics and everyone else have a duty to protect these people, and to avoid easy generalisations, whether malicious or well meant.

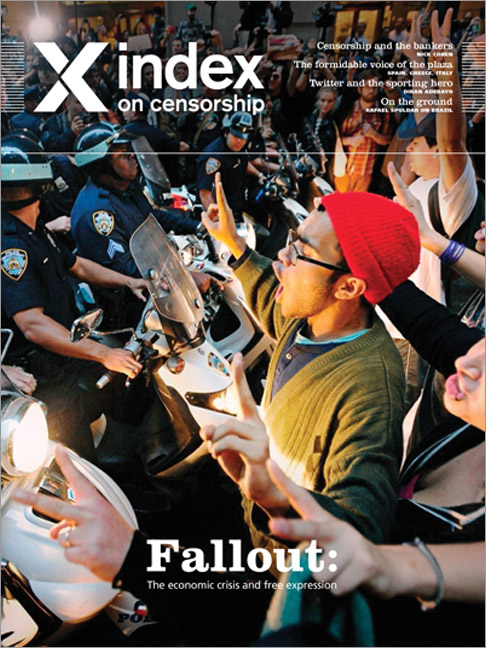

20 Mar 2013 | Press Releases, Volume 42.01 Spring 2013

As we prepare for Index’s annual freedom of expression awards, where we celebrate some of the world’s most courageous free speech heroes, we are delighted to announce the redesign of Index on Censorship magazine, published by SAGE. In addition to the in-depth journalism we’ve always placed at the heart of Index on Censorship, the magazine will feature a wider range of lively opinion snapshots, debates, views from the ground and interviews. A

“The magazine’s fresh new look reflects Index’s increasingly international outlook and role in setting the agenda for freedom of expression,” said Index Chief Executive Kirsty Hughes.

The new design was created by Matthew Hasteley, who said:

“Tackling a brief to modernise a magazine of Index’s heritage is a task you approach with a great degree of care and respect. The magazine balances the weight of its past accomplishments with its current, ongoing struggle against censorship around the globe, and the design need to reflect that tension — honouring the gravity of its editorial content.”

The latest issue, launched today, looks at new threats to free expression posed by the economic crisis, from restrictions on reporting and demonstrations to the rise of extremism. Is a decline in trust and a climate of self-censorship dominating the political, cultural and media landscape?

Christos Syllas looks at the threats to journalists and activists in crisis-stricken Greece and Spanish journalist Juan Luis Sánchez reports on the Spainish government’s moves towards criminalising one of the most powerful movements in recent years. The issue also features Natalie Haynes on political comedy and Nick Cohen on the secretive habits of big business and banking.

Our “In Focus” section will explore Index’s global themes, from digital censorship, government censorship and surveillance to religious and cultural pressures, restrictive laws and access to information. This issue also features Diran Adebayo on Twitter and the sporting hero and Dominique Lazanski on the future for online freedom.

If you would like an copy for review, please contact Pam Cowburn: [email protected]

Click here to subscribe.

16 Mar 2012 | Uncategorized

Journalist, author and free speech advocate Nick Cohen was, for a while, a lively presence on Twitter. He gave up the highly addictive site to work on his latest book, a polemic on censorship called You Can’t Read This Book (as more than one reviewer has pointed out, you can and should read this book).

Book completed and published, Cohen set out on the promotional slog required of authors, and rejoined Twitter 10 days ago in order to plug his work. After a few tweets alerting real-world friends to his presence, Cohen found his account (@NickCohen2) suspended, without explanation.

Bemused, Cohen tried to set up a new account (@NickCohen4), using a different email address. Again, Cohen sent a few tweets before finding the account suspended within hours.

Cohen is yet to have an explanation of the suspensions.

The irony to a free speech advocate being blocked from the web is clear, not least as Cohen praises Twitter in his book. But the Observer columnist has had previous trouble with his online profile. Cohen’s Wikipedia page was subjected to repeated slanderous edits by “David Rose”, later outed on the Jack of Kent blog as Independent journalist Johann Hari, who had a very public falling out with Cohen in the pages of Dissent magazine. “David Rose” was found to have maliciously edited several other “enemies” Wikipedia pages, including that of Telegraph blogger (and former colleague of Hari at the New Statesman) Christina Odone.

Update (15:55, 16 March) @NickCohen4 is operational again

16 Mar 2012 | Leveson Inquiry

England’s libel laws have turned the country into “liberty’s enemy”, Observer columnist and author of You Can’t Read This Book Nick Cohen said at last night’s launch of Index and English PEN’s final report of the Alternative Libel Project.

“We virtually invented freedom of expression, but any scoundrel can go to the High Court,” Cohen said.

He was among a host of libel reform campaigners speaking at yesterday’s event at London’s Inner Temple, reflecting on the strides made in the campaign and reaffirming the need for change in England’s defamation law.

The Alternative Libel Project, the result of a year-long inquiry looking into alternatives to resolving libel claims through the High Court, has recommended the use of quicker and cheaper methods to tackle the chilling costs of bringing a claim forward. The report advocates capping the cost of a libel claim at the average UK house price and allowing judges to protect ordinary people from having to pay the other side’s costs if they lose.

Cohen gave an impassioned defence of press freedom, noting that the proliferation of online publishing meant libel reform was no longer only an issue facing reporters. “Everyone is a journalist,” he said.

He praised the campaign’s efforts but urged supporters to look at the “cold climate into which this legislation is emerging”, comparing asking to do the press a favour to asking for a pay rise for MPs after the expenses scandal.

Science writer Simon Singh argued that issues of libel reform were not “old problems”, revealing that, in addition to battling a libel claim brought against him by the British Chiropractic Association, in 2010 he also received another threat over remarks he had made about climate change. The fear of libel, Singh said, was “widespread”.

Opening the event, Justice Minister Lord McNally echoed his statement made at yesterday’s Westminster Legal Policy Forum, saying that he would be “extremely disappointed” if a commitment to legislate of defamation was not part of the Queen’s Speech in May.

“This is not the end, not even the beginning of the end, but perhaps it is the end of the beginning,” he said.

Alternative Libel Project Final March 2012