18 Dec 2023 | Europe and Central Asia, News and features, Poland

The confirmation of Donald Tusk as Poland’s new prime minister, ending the right-wing Law and Justice (PiS) party’s eight year spell in power, offers cautious optimism that freedom of expression for the country’s minority groups will be better protected. Tusk’s appointment follows October’s parliamentary election, in which a broad coalition of opposition parties secured the majority of votes needed to form a government, which was officially voted in by MPs in December.

Throughout the eight years the PiS spent in power, freedom of expression in the country was continually eroded. Minority groups were targeted through strict legislation and judicial reform, while the party also tightened their grip on the media and encouraged far-right extremism.

One of the worst affected groups were LGBT+ people. In 2023, Poland was named as the worst country for LGBT+ rights in the EU in a report by watchdog ILGA-Europe for the third successive year. This is no surprise given the homophobic rhetoric pushed by the country’s leaders in recent years: PiS leader Jarosław Kaczyński claimed that LGBT+ people “threaten the Polish state”; former education minister Przemysław Czarnek likened what he called “LGBT ideology” to Nazism; and in 2019, Krakow’s archbishop described LGBT+ rights as a “rainbow plague”.

Spokesperson for the Love Does Not Exclude Association, a national non-governmental organisation fighting for marriage equality in Poland, Hubert Sobecki told Index that the organisation views the new government with “a mixture of hope and anxiety”.

They are hoping that the new Tusk-led coalition will pass laws legalising same-sex marriage, a concept that Sobecki explained is still seen as “radical” in the state, as well as addressing other issues such as same-sex parenthood and rising hate crimes, although he accused the polish leader of “slaloming” around these issues in the past.

“I do expect some actual specific concrete changes being made, legislative changes,” Sobecki said. “The current prime minister, Mr Tusk, we know him, we have a history, let’s call it that. He was quite reluctant to be remotely close to an allied position.”

It is clear that change won’t happen overnight. Eight years of the PiS in power has seen anti-LGBT+ sentiment rise throughout the country, with pride parades being targeted by violent counter-protesters and some regional governments passing resolutions to effectively make areas of the state an ‘LGBT-free zone’.

Sobecki’s descriptions of life in Poland in recent years paint a shocking portrait of the lived reality of LGBT+ people, who faced near constant abuse and discrimination in the state. He told of the increasing wave of people within the LGBT+ community who are struggling with mental illness, and those who have even had to migrate as a result of their treatment. During one incident, Sobecki recalled activists being targeted by police during a peaceful protest in Warsaw. “They were basically attacked, they were dragged on the pavement. Some people needed medical attention, some of them were molested after they got arrested. It’s mind-numbing,” he said.

However, Sobecki suggested that while the situation is bad, such incidents have also served to show just how much things needed to change. “It created a huge wave of support from people who thought ‘it’s too much’”, he explained. “After several years of this hate campaign being run, they can’t really shut it out anymore, they can’t remain blind to it.”

When asked whether he believed legislation would be enough to secure equality for LGBT+ people, Sobecki agreed that changed attitudes were as important as changed laws.

“What you need on the social level is visibility, storytelling techniques, constant campaigning, presence, representation, from the micro level of having dinner with your grandparents to the macro level of securing proper coverage on the main news channels,” he said.

However, there was still confidence that the government would make a difference. “What they can do is stop the hate in the public media. That is going to be a huge game changer,” he said. “You have millions of people who only watch one or two channels, who are effectively brainwashed. This change will be massive if it happens.”

Sobecki also pointed to moments, such as the recent ruling made by the European Court of Human Rights that Poland’s lack of legal recognition and protection for same-sex marriages breaches the European Convention on Human Rights, as evidence that progress is being made, albeit slowly.

“It was something that we’ve been working on for eight years, because those guys do take their time!” he said. “We knew that this was a message for the new government because the courts are savvy like that. We managed to get some responses from members of the new government who said ‘yes, this is a clear sign that we need to make a change’”.

The election results are also likely to be welcomed by proponents of women’s rights. During their years in power the PiS clamped down on reproductive rights in Poland, ending state funding for IVF and enforcing a prescription requirement for emergency contraception. Most significantly, Poland’s Constitutional Tribunal, an institution which critics say is heavily politicised by the PiS, implemented a near-total ban on abortion in the country in 2021, with the only exceptions being instances of rape, incest or a threat to health. As a result of this ruling, doctors and others who help women terminate pregnancies may face up to three years in prison, rising to eight if it occurs after the point of viability. These actions, which the PiS say have been made in an attempt to boost fertility rates and promote Catholic values, have had a disturbing effect on women’s freedoms in the state. Just this year, Polish activist Justyna Wydrzyńska was sentenced to 8 months’ community service for helping a pregnant woman to access abortion pills in what Amnesty International described as a “depressing low in the repression of reproductive rights in Poland” which serves as a “chilling snapshot of the consequences of such restrictive laws”.

Sobecki spoke about the need for change across all areas of society, as he argued that the PiS “weaponised the state” against a variety of social groups. “They basically attacked women’s rights openly as part of their agenda,” he said. “There’s a lot of pressure and expectation from the public for change, for something new, for something that is progressive.”

However, there are still concerns that even without PiS in power, the new Tusk-led government will not do enough to protect these rights. One feminist activist, Jana Shostak, was dropped by the opposition alliance after voicing support for wider abortion rights. She told the Guardian that her trust in Tusk to fight for women’s rights is “limited”.

There are concerns that the new government will resist calls for more progressive protections on rights and freedoms in an attempt to placate conservative voters. These worries extend beyond women and LGBT+ rights to immigration; Tusk warned of the “danger” of migrants and called for stricter border controls during a campaign speech which was denounced as racist and xenophobic by human rights NGOs.

The PiS being ousted from power sparked hope, but action from the new government to prevent women and minority groups from being silenced and threatened is much-needed. Sobecki vows to keep fighting: “At some point you just think it’s such a mess, what can you do? You just keep on doing what you’ve been doing, showing actual faces, actual people, telling their stories, trying to be hopeful that somehow it manages to get through.”

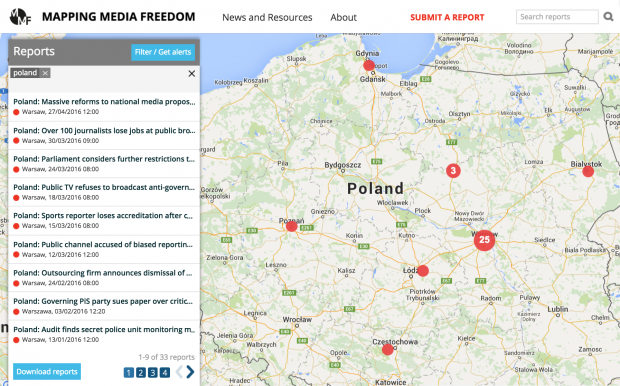

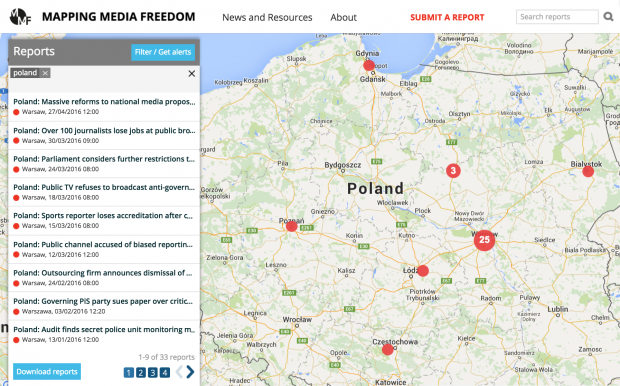

9 May 2016 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features, Poland

There’s no doubt that Poland’s media landscape is undergoing a rapid transformation. The country’s ranking in the Reporters Without Borders’ World Press Freedom Index plunged from 18 in 2015 to 47 in 2016. The government rushed through a law in the waning hours of 2015 that gave it oversight of the nation’s public broadcaster. Scores of veteran journalists have lost their jobs.

Further changes may be on the way as new media legislation, the so-called “big media law”, is being debated and proposals have been floated to restrict how journalists report from inside the Sejm.

Poland has been all about the “good change” since November 2015. The phrase goes back to a campaign video produced in May 2015 for the Law and Justice (PiS) party’s Andrzej Duda. The party went on to win the October 2015 elections and Duda became the sixth president of Poland.

Since the election, “good change” has been co-opted on Twitter as #dobrazmiana by critics opposed to the government’s legislation, which, in the case of the public broadcasters, is being implemented by Krzysztof Czabański, a former journalist and minister for culture and national heritage.

As part of the changes, a total of 141 journalists have been dismissed, forced to resign or transferred to lesser positions between the election and May 2016, according to journalist union Towarzystwo Dziennikarskie (TD). The “small media law” passed in late December 2015 meant the replacement of the managing board of public broadcasters TVP and Polskie Radio, which started a top-down dismissal process that is still ongoing.

Among the first wave of dismissals was Tomasz Lis, a TVP presenter who hosted a talk show and was a winner of the annual Hyena of the Year, an anti-prize for unreliability and disregard for the principles of journalistic ethics. The prize is awarded by the journalist union Stowarzyszenie Dziennikarzy Polskich (SDP), which is generally rather supportive of PiS. Teresa Bochwic, a member of the SDP management board, expressed a characteristic view in her assessment of the “good change”: “For better or for worse, the lying propaganda has stopped for good. On TV, there is regular information and pluralistic current affairs. Pro-governmental? Perhaps even sometimes pro-governmental, but at least not deceitful.”

Even among the sympathetic SDP, however, PiS’ moves towards increased restriction on the movement of journalists and the dismissal of Henryk Grzonka from Radio Katowice, where he had worked for almost 30 years and had recently served as editor-in-chief, has raised concerns.

TD, the youngest of Poland’s journalist unions, was founded in 2012 out of the realisation that “in journalism, we can no longer be together”, according to co-founder Seweryn Blumsztajn.

In an interview with Index on Censorship, TD co-founder Wojciech Maziarski said that the recent dismissals have the character of “political cleansing”, which started progressively from the top, and then moved gradually to the lower ranks of what he considers to be state media.

“The ones to bite the bullet first were journalists and editors of news and current affairs programmes, as they…have the biggest influence on public opinion,” he said.

“The state media is intended to shape citizens of the new, right-wing Poland, which means that gradually, all will be replaced who are associated with liberal thought, feminism, left-wing ideas, even if they don’t engage directly in topical political debates,” Maziarski added.

Apart from Lis and several other well-known personalities, dismissals included Dariusz Łukawski, vice-chair of the journalist section of TVP2, and lead correspondent Piotr Krasko at TVP1’s main news outlet Wiadomosci.

Later, the axings reached media workers from various programmes and ranks, which could also explain more recent dismissals or transfers in regional branches of the public TV and radio broadcasters. Throughout March and April, more cases emerged: Marta Bobowska from TVP Opole had to put down her work and leave mid-day on 12 April; and Wojciech Biedak, editor at Poznan’s Polskie Radio affiliated Radio Merkury.

According to Maziarski, the number of dismissals shows that state authorities view the media as “a frontline in a political war – and this line has to be stacked with trusted and tried soldiers”, which necessitates the exclusion of “not only critical journalists but everyone who thinks independently”.

This may have been the issue for TVP Info editors Izabela Leśkiewicz and Magdalena Siemiątkowska, who were dismissed from their posts in mid-March immediately after a dispute with station management. Leśkiewicz and Siemiątkowska disagreed with the portrayal of the anti-PiS NGO the Committee of Democratic Defence (KOD) in a segment to be aired. KOD was founded following PiS’s electoral success in late 2015 and has since been actively rallying public opinion to protest government policy around the country.

Monitoring body KRRiT has repeatedly accused TVP of bias in its reports on the civil society organisation. The day before another KOD demonstration, the managing board of TVP Info decided it would not air a live broadcast of the beginning of the march, and specific narratives on “how KOD is hating on normal citizens” would be shown instead. Leśkiewicz and Siemiątkowska were dissatisfied with this and offered an alternative, more nuanced programme set-up. TVP Info management then fired the pair. Two other TVP journalists, Agata Całkowska and Łukasz Kowalski, resigned in protest.

Currently, new media legislation is being considered in parliament. This draft law would amount to a structural and financial overhaul of the public broadcaster. Under the draft, heads of the new “national media” outlets would be “appointed by a six-person National Media Council elected by the lower house of parliament, the Senate and the president for a six-year term” with one of the council slots legally guaranteed for the largest opposition caucus, according to Radio Poland. The proposed law would also replace the current license fee with a monthly “audiovisual” charge added to Poles’ electric bills beginning in January 2017.

Unlike Poland‘s three other journalists’ unions, Towarzystwo Dziennikarskie is boycotting the draft media law consultation being conducted by the minister for cultural affairs. Maziarski explains the union’s standpoint: “A big problem for public media in Poland is their financing. The introduction of a general audio-visual fee has been one of the main demands of the journalist environment. However, the fee introduced through the proposed law is intended to serve the maintenance of an indoctrination machinery and the PiS propaganda rather than public media. In effect, public media in Poland have ceased to exist.”

19 Apr 2016 | Academic Freedom, Europe and Central Asia, mobile, News and features, Poland

Jan Gross (Princeton)

A Polish prosecutor has interrogated Jan Gross, a Polish-American professor of history at Princeton University, to determine whether claims he made that Poles “had killed more Jews than the Germans” during World War II constitute a crime.

Insulting the nation is punishable by up to three years in jail in Poland.

“The ability to question established narratives is vital to academic freedom and a free and progressive society,” Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of Index on Censorship, said.

Gross, who has researched Polish complicity in the Holocaust, said he was questioned as a witness for five hours on Tuesday 12 April in the district attorney’s office in Katowice but has not been charged with a crime.

Complaints were filed by Polish citizens over Gross’ claims, which were made in an article published in Project Syndicate last September. In it, the historian also argued that Poland’s opposition to accepting asylum seekers could be linked to its “murderous past”.

“I said straight out that I was not going to offend the Polish nation,” Gross told the Associated Press regarding his recent questioning. “I tried to make people aware of the problem of refugees in Europe. I’m just telling the truth, and the truth sometimes has the effect of shock on people who previously were not aware of the case.”

In February Index reported that Polish President Andrzej Duda considered stripping Gross of an Order of Merit over his academic work on Polish anti-Semitism. Gross outlined in his 2001 book Neighbors that the massacre of some 1,600 Jews from the Polish village of Jedwabne in July 1941 was committed by Poles, not Nazis.

24 Feb 2016 | Academic Freedom, Europe and Central Asia, mobile, News and features, Poland

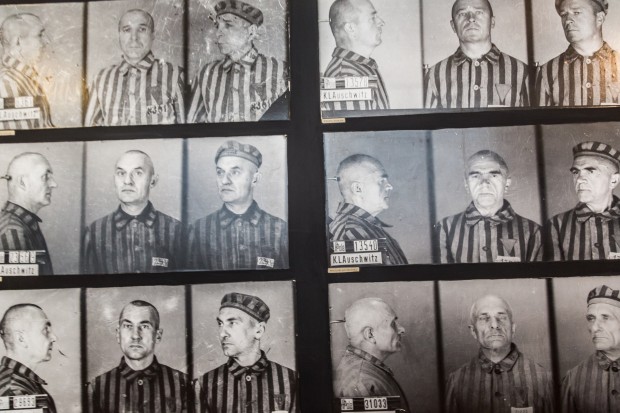

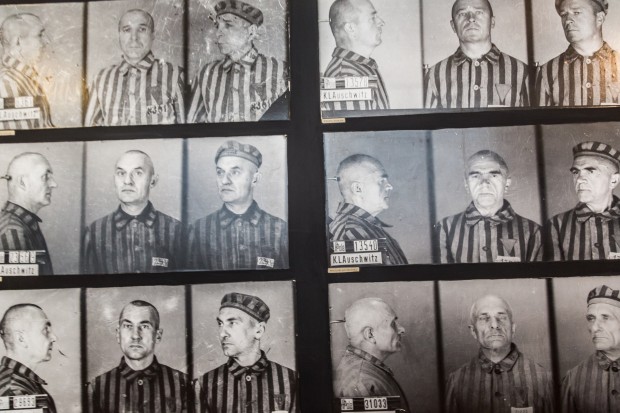

Still from an Auschwitz exhibition, 22 July 2014 in Oswiecim, Poland

When discussing academic freedom more than a century ago, German sociologist and philosopher Max Weber wrote: “The first task of a competent teacher is to teach his students to acknowledge inconvenient facts.” In Poland today, history appears to be an inconvenience for the ruling Law and Justice (PiS) party, which is introducing legislation to punish the use of the term “Polish death camps”.

The Polish justice minister Zbigniew Ziobro announced earlier this month that the use of the phrase in reference to wartime Nazi concentration camps in Poland could now be punishable with up to five years in prison. If enacted, Poland would find itself in the unique position of being a country where both denying and discussing the Holocaust could land you in trouble with the law. Holocaust denial has been outlawed in Poland — under punishment of three years “deprivation of liberty” — since 1998.

Any suggestion of Polish complicity in Nazi war crimes against Jews brings with it, in the party’s own words, a “humiliation of the Polish nation”.

Of course, Poland was an occupied country which suffered terribly under Nazi Germany, so any talk of acquiescence understandably hits a nerve. As all good history students know, however, the discipline has its ambiguities and competing theories, from the acclaimed to the crackpot, and singular, simplistic narratives are rare. But few democratic countries in the world punish those who argue unpopular historical positions. Which is why legislating against uneasy truths is the same as legislating against academic freedom.

Two recent examples show the Polish government of doing just this. Firstly, Poland’s President Andrzej Duda made public his serious consideration to stripping the Polish-American Princeton professor of history at Princeton University Jan Gross of an Order of Merit — which he received in 1996 both for activities as a dissident in communist Poland in the 1960s and for his scholarship — over his academic work on Polish anti-Semitism. Gross outlined in his 2001 book Neighbors that the massacre of some 1,600 Jews from the Polish village of Jedwabne in July 1941 was committed by Poles, not Nazis. More recently, the historian has claimed that Poles killed more Jews than they did Germans during the war, which prompted the current action against him.

Some who disagree with his arguments have labelled Gross an “enemy” of Poland and a “traitor to the motherland”. The historian has hit back, saying in an interview with the Associated Press: “They want to take [the Order of Merit] away from me for saying what a right-wing, nationalist, xenophobic segment of the population refuses to recognise as facts of history.”

Academics too — Polish and otherwise — have come to his defence. Agata Bielik-Robson, professor of Jewish Studies at Nottingham University, points out that a “democracy has to have a voice of inner criticism”. She is worried that PiS is seeking to do away with such criticism in order “to produce a uniform historical perspective”.

Polish journalist and former activist in the anti-communist Polish trade union Solidarity Konstanty Gebert explained to Index on Censorship that PiS has made “convenient scapegoats” of people like Gross. “PiS is moving fast to reestablish a ‘positive narrative of Polish history’ by breaking with an alleged ‘pedagogy of shame’,” he said.

The party first tried — unsuccessfully — to outlaw the term “Polish death camps” in 2013 when it was in opposition. Should the law now pass, and you need help adhering to the proposed rules, the Auschwitz Museum has released an app to correct any “memory errors” you may experience. It detects thought crimes such as the words “Polish concentration camp” in 16 different languages on your computer, keeping you on the right track with prompts asking if you instead meant to write “German concentration camp”.

Poland may have lurched to the right with the election of PiS last October, but the party’s authoritarianism — from crackdowns on the media to moves to take control of the supreme court — seems positively Soviet in some respects. Attempts to control history, too hark back to the Polish People’s Republic of 1945-1989, when, in the words of Elizabeth Kridl Valkenier in the winter 1985 issue of Slavic Review, “cultural patterns” and “habits of mind” made it impossible to make historical interpretations “alien to that national sense of identity and a methodology at odds with the canons and objective scholarship”.

Gebert sees similarities between current and communist-era propaganda “in the basic formulation that there is nothing to be ashamed of in Polish history, and in Polish-Jewish relations in particular, and in the belief that there is one correct national viewpoint”.

However, now that freedom of speech exists, the government can and are being criticised for their actions. “This puts the government propaganda machine on the defensive,” Gebert said.

Just last week, President Duda spoke against the “defamation” of the Polish people “through the hypocrisy of history and the creation of facts that never took place”. He has made his motives clear: “Today, our great responsibility to create a framework […] with the dual aim of fostering a greater sense of patriotic pride at home while enhancing the country’s image abroad.”

It should be intolerable for the freedoms of any academic subject to be impinged for ideological ends. If academic freedom is to mean anything, it should include the right to tell uneasy truths, get things wrong and have you work challenged by the highest academic standards.

There’s only one place to turn for PiS to find an example of best practice on how to challenge Gross’ research, and that is to the very body the party will grant authority to on deciding on what is and isn’t a breach of the law regarding “Polish death camps”. Poland’s Institute of National Remembrance (IPN) produced several reports between 2000-03 challenging claims in Gross’ book on the Jedwabne massacre. It used research and reason — as opposed to censorship — to make the case that the historian didn’t get all the facts right. It found, for example, that German’s played a bigger part in the slaughter than Gross had claimed, and that the numbers killed were more likely to be around the 340 mark, rather than 1,600.

IPN should tread carefully, though. Any inconvenient truths with the potential to humiliate the Polish people could one day soon see it branded a “traitor”.

Ryan McChrystal is the assistant editor, online at Index on Censorship