27 Feb 2021 | News, Russia, Statements

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”116328″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship was established to provide a voice for dissidents living either under authoritarian regimes or in exile. Throughout our history extraordinary people have written for us and we have campaigned for their freedom. Every time Index seeks to intervene there is obviously a consideration made about who we seek to shine a light on and which regimes are of concern but the reality is we don’t get to choose dissident leaders and we don’t get to choose who inspires a movement. Our role is simple – we are here to campaign for equal access to Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. We may not like the actions of some dissidents, we may not like how they have used their rights to free expression – but we exist to ensure that they have that right.

Index operates from a position of luxury, from the security of a democratic country. Our human rights are protected in law. For far too many people in the world that is not the case. Which brings me to the case of Alexei Navalny – we may find his comments as a younger man abhorrent, but his actions as a dissident leader cannot be questioned. His ability to inspire a nation to challenge an authoritarian regime is extraordinary. And the fact that he has nearly lost his life in an attempted chemical poisoning is beyond doubt. Navalny is a political prisoner. He is a dissident. He deserves our solidarity.

Index stands with Navalny.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

19 Oct 2020 | News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

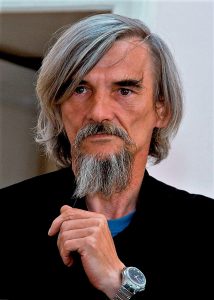

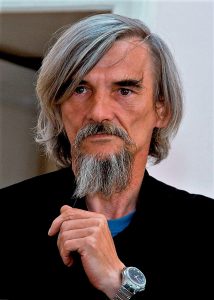

Russian historian Yuri Dmitriev, who has been imprisoned following research into murders committed by Stalin. Credit: Mediafond/Wikimedia

Western democracies have expressed concern and outrage, at least verbally, over the Novichok poisoning of Alexei Navalny—and this is clearly right and necessary. But much less attention is being paid to the case of Yuri Dmitriev, a tenacious researcher and activist who campaigned to create a memorial to the victims of Stalinist terror in Karelia, a province in Russia’s far northwest, bordering Finland. He has just been condemned on appeal by the Supreme Court of Karelia to thirteen years in a prison camp with a harsh regime.

The hearing was held in camera, with neither him nor his lawyer present. For this man of sixty-four, this is practically equivalent to a death sentence, the judicially sanctioned equivalent of a drop of nerve agent.

After an initial charge of child pornography was dismissed, Yuri Dmitriev was convicted of sexually assaulting his adoptive daughter. These defamatory charges appear to be the latest fabrication of a legal system in thrall to the FSB—a contemporary equivalent, here, of the nonsensical slander of “Hitlerian Trotskyism” that drove the Great Terror trials. It is these same charges, probably freighted with a notion of Western moral decadence in the twisted imagination of Russian police officers, that were brought in 2015 against the former director of the Alliance Française in Irkutsk, Yoann Barbereau.

I met Yuri Dmitriev twice: the first time in May 2012, when I was planning the shooting of a documentary on the library of the Solovki Islands labor camp, the first gulag of the Soviet system; and the second in December 2013, when I was researching my book Le Météorologue (Stalin’s Meteorologist, 2017), on the life, deportation, and death of one of the innumerable victims murdered by Stalin’s secret police organizations, OGPU and NKVD.

In both cases, Dmitriev’s help was invaluable to me. He was not a typical historian. At the time of our first meeting, he was living amid rusting gantries, bent pipes, and machine carcasses, in a shack in the middle of a disused industrial zone on the outskirts of Petrozavodsk—sadly, a very Russian landscape. Emaciated and bearded, with a gray ponytail, he appeared a cross between a Holy Fool and a veteran pirate—again, very Russian. He told me how he had found his vocation as a researcher—a word that can be understood in several senses: in archives, but also on the ground, in the cemetery-forests of Karelia.

In 1989, he told me, a mechanical digger had unearthed some bones by chance. Since no one, no authority, was prepared to take on the task of burying with dignity those remains, which he recognized as being of the victims of what is known there as “the repression” (repressia), he undertook to do so himself. Dmitriev’s father had then revealed to him that his own father, Yuri’s grandfather, had been shot in 1938.

“Then,” Dmitriev told me, “I wanted to find out about the fate of those people.” After several years’ digging in the FSB archive, he published The Karelian Lists of Remembrance in 2002, which, at the time, contained notes on 15,000 victims of the Terror.

“I was not allowed to photocopy. I brought a dictaphone to record the names and then I wrote them out at home,” he said. “For four or five years, I went to bed with one word in my head: rastrelian—shot. Then, I and two fellow researchers from the Memorial association, Irina Flighe and Veniamin Ioffe (and my dog Witch), discovered the Sandarmokh mass burial ground: hundreds of graves in the forest near Medvejegorsk, more than 7,000 so-called enemies of the people killed there with a bullet through the base of the skull at the end of the 1930s.”

Among them, in fact, was my meteorologist. On a rock at the entrance to this woodland burial ground is this simple Cyrillic inscription: ЛЮДИ, НЕ УБИВАЙТЕ ДРУГ ДРУГА (People, do not kill one another). No call for revenge, or for putting history on trial; only an appeal to a higher law.

Memorials to the victims of Stalin’s Terror at Krasny Bor, Karelia, 2018; the remains of more than a thousand people shot between 1937 and 1938 at this NKVD killing field were identified by Dmitriev, using KGB archival records

Not content to persecute and dishonor the man who discovered Sandarmokh, the Russian authorities are now trying to repeat the same lie the Soviet authorities told about Katyn, the forest in Poland where NKVD troops executed some 22,000 Poles, virtually the country’s entire officer corps and intelligentsia—an atrocity that for decades they blamed on the Nazis. Stalin’s heirs today claim that the dead lying there in Karelia were not victims of the Terror but Soviet prisoners of war executed during the Finnish occupation of the region at the beginning of World War II. Historical revisionism, under Putin, knows no bounds.

I am neither a historian nor a specialist on Russia; what I write comes from the conviction that this country, for which I have a fondness, in spite of all, can only be free if it confronts its past—and to do this, it needs courageous mavericks like Yuri Dmitriev. And I write from the more personal conviction that he is a brave and upright man, one whom Western governments should be proud to support.

This article was translated from the French by Ros Schwartz. It was originally published on the New York Review of the Books here under the headline Yuri Dmitriev: Historian of Stalin’s Gulag, Victim of Putin’s Repression.

Read our article exploring Dmitriev’s case and how history is being manipulated and erased here.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

15 Sep 2020 | Belarus, News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”114819″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]On 9 August, Belarus went to the polls to elect their president. Alexander Lukashenko, who has been in power since 1994, was seeking a fifth term.

When the result was announced, Lukashenko had won 80% of the vote. However, the Belarusian people believed the election was rigged and took to the streets in their thousands to protest peacefully.

One of those protesting was 73-year-old great grandmother Nina Bahinskaya, who has become a famous face on the streets of Minsk as she squares up to Lukashenko’s riot police.

She has been arrested and fined half of her pension but still comes back for more.

Index on Censorship’s associate editor Mark Frary spoke with her to find out how she became an unlikely protestor, why she always carries a flag and whether she fears for her safety in the face of police brutality.

With thanks to Franak Viacorka, Radio Free Europe, Euroradio and Alina Stefanovic (interpreter).[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/4Ap8jtyRVKc”][/vc_column][/vc_row]

16 Jan 2020 | News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”111830″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]“When I talk about what’s happening in Saudi Arabia, I liken it to a really abusive relationship. First they [the state] gaslight you, they try to convince you that you’re not being abused, that this actually is for your own protection, for your best interests. Then when that doesn’t work out, then they beat you up and… when you escape from them they hunt you down and kill you,” said Safa Al Ahmad, award-winning Saudi Arabian journalist, at the launch of the winter 2019 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

The issue is on the techniques that macho leaders around the world are using to stifle dissent, democracy and discussion, and how people are fighting back. From Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro ranting against and disparaging media to Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orbán using a rhetoric of family values to deny the LGBT community and others the same rights as “traditional” nuclear families, the magazine takes a global view.

Al Ahmad was joined for a panel discussion, held at Google HQ in London, with bestselling Chinese novelist Xiaolu Guo, Hungarian activist Dóra Papp and satirist and author Rob Sears. The panel was chaired by Rachael Jolley, editor-in-chief of Index on Censorship magazine.

Each panellist was invited to discuss a world leader. Al Ahmad opened with her striking analogy of abusive relationships to discuss Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia Mohammed bin Salman. She highlighted that her analogy was not an exaggeration, citing women’s rights campaigners who have ended up dead or in prison. “I think the feminist movement in Saudi must have been the most frightening for the state,” she said, explaining the lengths the state has gone to in order to silence women.

Al Ahmad also remarked on the absolutist relationship the Saudi state has with the media: “We [Saudi Arabia] have inventing the rulebook on shutting down dissent of any sort, so the state owns all the media. There is no independent media whatsoever to shut buyout – they already own it.”

Papp observed that Orbán has not locked up or killed dissenters “yet”, but that he is at the stage of attempting to create a sense of discord amongst Hungarians, thereby preventing unified protest. She said: “What this kind of leadership from Orbán is really pro in is… making the nation believe that they have to stay divided in order to protect their own identities and their own values.”

Family values is part of the rhetoric of Orbán’s government, which “concludes in a list of disadvantages for LGBT groups, for single mothers, for anyone who is thinking outside the box”. Papp, a successful campaigner, said that we need to be really cautious and not let this narrative divide people.

Guo, discussing China’s president Xi Jinping, spoke about the importance of a dominating personality in a “strongman” leader in order to control the narrative of a country. She said of Xi: “He has an extremely tough way of dealing with internal turmoil but also a very interesting and mysterious way of dealing with international conflict.” She also commented that tension between Xi and US President Donald Trump seems to be bringing about a cold war that “we thought had disappeared 20 years ago”.

A discussion about macho men would not be complete without a dissection of the presidency of Trump, which Sears did by observing how Trump stifles free expression, not by killing journalists, but by setting the media agenda. Sears highlighted two of Trump’s oratory traits: “One is that he is basically impossible to ignore and the other is that he is basically impossible to engage with.”

He explains that Trump’s repeated use of outrageous, implausible (think “build the wall” and “lock her up”) but clear images forces the media to report on them. He said: “You [journalists] can’t help but respond to them and make them the focus of attention, meaning that it’s tricky for other topics to make it into the highest levels of conversation.”

“I’m sure every politician finds the right language for that purpose. UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson cleary does and some of the other leaders we’ve talked about do as well… I don’t know if they are deliberate methods… but I do think that it’s been extremely effective against a decent, fruitful public debate in the states and worldwide.”

Click here to read more about the current magazine

Listen to Rachael Jolley and deputy editor of the magazine, Jemimah Steinfeld, discuss the current issue on Resonance radio here [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row]