15 Dec 2014 | About Index, Draw the Line, Young Writers / Artists Programme

Religious freedom and religious radicalism which leads to extremism has become an increasingly difficult balancing act in the digital age where presenting religious superiority through fear and “terror” is possible both locally and internationally at internet speeds.

The ongoing series of beheading videos released by the Islamic State and the showcase of kidnapped school girls by Nigeria’s Boko Haram on YouTube are both examples that test the extent to which the UN Convention of Human Rights can protect religious freedoms. According to a report by the International Humanist and Ethical Union, Egypt’s Youth Ministry are targeting young atheists vocal on social media about the dangers of religion. In Saudi Arabia, Raef Badawi was sentenced to seven years in prison in 2013 and received 600 lashes for discussing other versions of Islam, besides Wahhabism, online.

Article 18 of the Convention states that the “right includes freedom to change his religion or belief, and freedom, either alone or in community with others and in public or private to manifest his religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship and observance”. The interpretation of “practice” is a grey area – especially when the idea of violence as a form of punishment can be understood differently across various cultures. Is it right to criticise societies operating under Sharia law that include amputation as punishment, ‘hadd’ offences that include theft, and stoning for committing adultery?

Religious extremism should not only be questioned under the categories of violence or social unrest. Earlier this month, religious preservation in India has led to the banning of a Bollywood film scene deemed ‘un-Islamic’ in values. The actress in question was from Pakistan, and sentenced to 26 years in prison for acting out a marriage scene depicting the Prophet Muhammad’s daughter. In Russia, the state has banned the publication of Jehovah’s Witness material as the views are considered extremist.

In an environment where religious freedom is tested under different laws and cultures, where do you draw the line on international grounds to foster positive forms of belief?

This article was posted on 15 December 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

4 Jun 2014 | Brazil, News and features, Religion and Culture

An inter-religious meeting at the Maracanã stadium in Rio de Janeiro to mark the beginning of the Peace Cup campaign (Tomaz Silva/Brazil Agency)

A request to remove 16 videos from YouTube has sparked a broad debate on the limits of freedom of speech and religious expression in Brazil. According to the complaint by the National Association of African Media, filed to the Regional Prosecutor’s Office of Rio de Janeiro (MPF), the videos encourage intolerance and prejudice against religious practices of African origin (Candomblé and Umbanda). The videos were posted by the Igreja Universal do Reino de Deus (IURD), a Neo-Pentecostal church.

The federal prosecutors from the MPF asked Google Brazil to remove the videos. But Google refused, arguing that the material disclosed “would be nothing more than the manifestation of the religious freedom of the Brazilian people” and that the videos “did not violate the company’s policy”.

On 17 May, the issue was taken to the federal court in Rio de Janeiro. There, judge Eugenio Rosa de Araújo denied the request for the removal of the videos. “Its contents are manifestations of free expression of opinion,” he stated. He argued that “the African-Brazilian religious practices do not constitute a religion” because “the religious manifestations (African) do not contain necessary traits of a religion”. He stated that a religion needs to have traits such as a baseline text (“as the Bible or the Koran”), a hierarchical structure and one God to be worshiped.

Notably, the ruling has two parts: the first determines that the videos are to be kept online, and is based on the right to freedom of expression. In the second part of the sentence, the judge defines what religion is, and excludes religions with African-Brazilian origin from this scope.

The representative of the Commission Against Religious Intolerance, Ivanir dos Santos, accused the judge of encouraging prejudice. “He is an employee of a laic State and is submitted to the Brazilian constitution and laws. He violated the constitution and the law against the racial discrimination.”

Facing such strong reaction, the judge Eugenio de Araujo Rosa went back on his decision. In a statement, he admitted he made a mistake and revised his sentence. “The strong support of the media and civil society demonstrates unquestionably the belief in the worship of such religions,” he said, referring to African-Brazilian beliefs.

But the original position of the judge is still causing reactions. The Order of Lawyers of Brazil repudiated the ruling, while the MPF has filed an appeal, arguing that “the decision mistreats the awareness, the honour and the dignity of millions of Brazilians who recognise themselves in these religions”. Protests by African-Brazilian culture organisations were held in at least seven cities. Leaders of all Brazilian beliefs gathered at Maracanã Stadium, calling for more peace and religious tolerance.

In addition, representatives from the MPF will file a lawsuit to the Superior Court of Justice (STJ), one of the highest organisations in the Brazilian judiciary system, against Judge Eugênio Rosa de Araújo. “Our intention is to remove the videos. It is not about freedom of expression, but about the spread of hatred,” said Santos.

On 28 May, the Federal Regional Court (TRF) received a petition with 1,000 signatures, demanding the removal of the videos. The petition was organised by the Commission Against Religious Intolerance and the National Association of African Media. The representatives of the afro culture argue the court’s decision to keep the videos on the internet violates the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 129 of the Brazilian Constitution, and the Statute of Racial Equality (Law 12.288/2010). The statute stipulates that the government must protect the communities of African origin from hateful content in the media. The law forbids “the use of the media to disseminate images and contents that expose a person or group to hatred or contempt on the grounds of religion with African roots”.

FuA national demonstration against prejudice towards African-Brazilian religions has been scheduled. The event is organised by various associations for the defence of black culture, with the support of the Order of Lawyers of Brazil, the National Council of Justice (CNJ), the Human Rights Commission of Congress national and the Organization of American States (OAS). In congress, the Parliamentary Front in Defence of “Traditional Peoples of Terreiro” was created, aiming to institutionalise the defence of religions of African origin. The bloc will be a counterpoint to the Evangelical Parliamentary Front, which brings together 77 congressmen who form the base of support for the government of Dilma Rousseff.

“The theme is of utmost importance, because [it] involves guarantees which the constitution itself assures. I hope that it resolves itself quickly,” the President of the Federal Court, Sérgio Schwaitzer, told the Jornal do Brasil.

According Edson Santos, the deputy of PT (Workers Party) and former minister of racial equality, the judge encouraged the prejudice against African-Brazilian sects. He argued that the magistrate will be denounced at the National Council of Justice. “The decision was absurd and deeply regrettable, because it hurts the constitution”, he told to the newspaper Folha de S. Paulo.

“This conflict of law is challenging and raises questions about the limits of freedom of expression,” said Professor of Philosophy of Law José Rodrigo Rodriguez, of Law School of São Paulo from the Fundação Getúlio Vargas. Analysing the topic in an article, he argues that “one can say, without fear of any excess, that the decision has a clear discriminatory effect, despite the certainly good intention of the judge”.

This article was posted on June 4, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

29 May 2014 | News and features, Religion and Culture, United Kingdom

Pastor James McConnell

Belfast’s Whitewell Metropolitan Tabernacle is one of those things that makes a soft Southern Irish atheist Catholic like me think I’ll never truly understand Northern Ireland.

Every week, Ulster Christians flock from across the province to the 3,000-seater auditorium, there to hear Pastor James McConnell preach his Christian message. Not the Christian message of the BBC’s Thought For The Day, however; you may hear Beatitudes at Whitewell, but it’s not a place for platitudes. This is the real deal, fire and brimstone; damnation and salvation. If you’re not going to Whitewell, you’re going to Hell.

It is a comforting message, and actually, a very modern one. Think of how many politicians these days talk about how they work for hard-working-families-that-play-by-the-rules. Hardline evangelical Christianity is the epitome of that idea. We don’t refer to the “Protestant Work Ethic” for nothing.

But what we tend to forget when discussing hardliners from the outside is that there is a strong apocalyptic element in orthodox monotheistic religion. This is particularly true of Christianity. The closer to the core you get, the more you find Jesus’s teachings are essentially about the end of the world, not some vague being-nice-to-one-another schtick.

For some time, Christians have fretted over Matthew 24, in which Jesus apparently tells of the signs of his second coming, that is, to, say, the end of the world. What worries them particularly is Matthew 24:34: “Verily I say unto you, This generation shall not pass, till all these things be fulfilled.”

Does this mean Jesus was telling his apostles that the world would end in their lifetime? CS Lewis, in his work The World’s Last Night, seemed to believe so, and went so far as to call the Messiah’s assertion “embarrassing”. Lewis wrote:

“‘Say what you like,’ we shall be told, ‘the apocalyptic beliefs of the first Christians have been proved to be false. It is clear from the New Testament that they all expected the Second Coming in their own lifetime. And, worse still, they had a reason, and one which you will find very embarrassing. Their Master had told them so. He shared, and indeed created, their delusion. He said in so many words, ‘This generation shall not pass till all these things be done.’ And he was wrong. He clearly knew no more about the end of the world than anyone else.”

“It is certainly the most embarrassing verse in the Bible. Yet how teasing, also, that within fourteen words of it should come the statement ‘But of that day and that hour knoweth no man, no, not the angels which are in heaven, neither the Son, but the Father.’ The one exhibition of error and the one confession of ignorance grow side by side.”

Lewis, though himself a Northern Irish Protestant, was clearly not of the same cloth as Pastor McConnnell, Ian Paisley, and the other preachers of their ilk. Orwell disdained Lewis for his efforts to “persuade the suspicious reader, or listener, that one can be a Christian and a ‘jolly good chap’ at the same time.” The booming pastors of Northern Ireland, and other Christian strongholds such as the US’s Bible Belt, are very firmly convinced that the end is imminent. And thus, they do not have time to be “jolly nice chaps”. There are souls to be saved, right now.

It’s this attitude that has got Pastor McConnell into trouble in the past week. Recently, at Whitewell, inspired by the story of Meriam Yehya Ibrahim, a Sudanese woman reportedly sentenced to death for converting to Christianity, McConnell told the thousands assembled at his temple that “”Islam is heathen, Islam is Satanic, Islam is a doctrine spawned in Hell.”

In an interview with the BBC’s Stephen Nolan, McConnell refused to back down, claiming that all Muslims had a duty to impose Sharia law on the world, and suggesting they were all merely waiting for a signal to go to Holy War. A subtle examination of modern Islamist and jihadist politics this was not.

The PSNI is now investigating McConnell for hate speech. Northern Ireland’s politcians have been quick to comment. First Minister Peter Robinson backed McConnell, first saying that the preacher did not have an ounce of hate in his body, and then managing to make the situation worse by saying he would not trust Muslims on spiritual issues, but would trust a Muslim to “go down the shops for him”.

Insensitive and patronising that may be, but Robinson also touched on something more relevant to this publication when he said that Christian preachers had a responsibility to speak out on “false doctrines”.

The issue raised is this: if we genuinely believe something to be untrue, no matter how misguided we may be, do we not have a right to challenge it in robust terms? In politics we often bemoan the fact that leaders will not call things as they, or we, see them: indeed, Tony Blair, the bete noire of pretty much every political faction in Britain (a bete noire who oddly managed to win three election) has found grudging praise from across the spectrum this week for suggesting that rather than “listening to” or “understanding” the xenophobic United Kingdom Independence Party, politicians should tackle their arguments head on.

But in religion, we tend to hope that no one will upset anyone too much, in spite of the fact that, for true believers, theological issues are far more important than taxation or anything else.

When Blair’s government proposed (and eventually passed) a law against incitement to religious hatred in Britain, the opposition came from a coalition of secularists and some evangelical Christians, both groups realising, for different reasons, that being able to call an ideology false or untrue – and in the process criticise and question its adherents – was a fundamental right. The trade off in that is acknowledging others’ right to question your truths, something I suspect, judging by the recent controversy in Northern Ireland over a satirical revue based on the Bible, Pastor McConnell and his supporters may not quite excel at.

This article was originally posted on May 29, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

30 Apr 2014 | Egypt, Iraq, News and features, Nigeria, Pakistan, Religion and Culture, Syria, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Vietnam

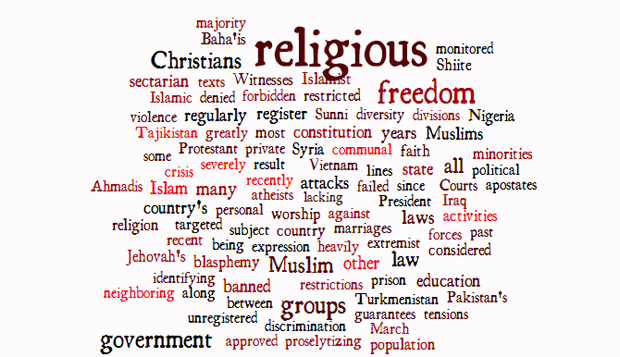

In January, Index summarised the U.S. State Department’s “Countries of Particular Concern” — those that severely violate religious freedom rights within their borders. This list has remained static since 2006 and includes Burma, China, Eritrea, Iran, North Korea, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, and Uzbekistan. These countries not only suppress religious expression, they systematically torture and detain people who cross political and social red lines around faith.

Today the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF), an independent watchdog panel created by Congress to review international religious freedom conditions, released its 15th annual report recommending that the State Department double its list of worst offenders to include Egypt, Iraq, Nigeria, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Vietnam and Syria.

Here’s a roundup of the systematic, ongoing and egregious religious freedom violations unfolding in each.

1. Egypt

The promise of religious freedom that came with a revised constitution and ousted Islamist president last year has yet to transpire. An increasing number of dissident Sunnis, Coptic Christians, Shiite Muslims, atheists and other religious minorities are being arrested for “ridiculing or insulting heavenly religions or inciting sectarian strife” under the country’s blasphemy law. Attacks against these groups are seldom investigated. Freedom of belief is theoretically “absolute” in the new constitution approved in January, but only for Muslims, Christians and Jews. Baha’is are considered apostates, denied state identity cards and banned from engaging in public religious activities, as are Jehovah’s Witnesses. Egyptian courts sentenced 529 Islamist supporters to death in March and another 683 in April, though most of the March sentences have been commuted to life in prison. Courts also recently upheld the five-year prison sentence of writer Karam Saber, who allegedly committed blasphemy in his work.

2. Iraq

Iraq’s constitution guarantees religious freedom, but the government has largely failed to prevent religiously-motivated sectarian attacks. About two-thirds of Iraqi residents identify as Shiite and one-third as Sunni. Christians, Yezidis, Sabean-Mandaeans and other faith groups are dwindling as these minorities and atheists flee the country amid discrimination, persecution and fear. Baha’is, long considered apostates, are banned, as are followers of Wahhabism. Sunni-Shia tensions have been exacerbated recently by the crisis in neighboring Syria and extremist attacks against religious pilgrims on religious holidays. A proposed personal status law favoring Shiism is expected to deepen divisions if passed and has been heavily criticized for allowing girls to marry as young as nine.

3. Nigeria

Nigeria is roughly divided north-south between Islam and Christianity with a sprinkling of indigenous faiths throughout. Sectarian tensions along these geographic lines are further complicated by ethnic, political and economic divisions. Laws in Nigeria protect religious freedom, but rule of law is severely lacking. As a result, the government has failed to stop Islamist group Boko Haram from terrorizing and methodically slaughtering Christians and Muslim critics. An estimated 16,000 people have been killed and many houses of worship destroyed in the past 15 years as a result of violence between Christians and Muslims. The vast majority of these crimes have gone unpunished. Christians in Muslim-majority northern states regularly complain of discrimination in the spheres of education, employment, land ownership and media.

4. Pakistan

Pakistan’s record on religious freedom is dismal. Harsh anti-blasphemy laws are regularly evoked to settle personal and communal scores. Although no one has been executed for blasphemy in the past 25 years, dozens charged with the crime have fallen victim to vigilantism with impunity. Violent extremists from among Pakistan’s Taliban and Sunni Muslim majority regularly target the country’s many religious minorities, which include Shiites, Sufis, Christians, Hindus, Zoroastrians, Sikhs, Buddhists and Baha’is. Ahmadis are considered heretics and are prevented from identifying as Muslim, as the case of British Ahmadi Masud Ahmad made all too clear in recent months. Ahmadis are politically disenfranchised and Hindu marriages are not state-recognized. Laws must be consistent with Islam, the state religion, and freedom of expression is constitutionally “subject to any reasonable restrictions imposed by law in the interest of the glory of Islam,” fostering a culture of self-censorship.

5. Tajikistan

Religious freedom has rapidly deteriorated since Tajikistan’s 2009 religion law severely curtailed free exercise. Muslims, who represent 90 percent of the population, are heavily monitored and restricted in terms of education, dress, pilgrimage participation, imam selection and sermon content. All religious groups must register with the government. Proselytizing and private religious education are forbidden, minors are banned from participating in most religious activities and Muslim women face many restrictions on communal worship. Jehovah’s Witnesses have been banned from the country since 2007 for their conscientious objection to military service, as have several other religious groups. Hundreds of unregistered mosques have been closed in recent years, and “inappropriate” religious texts are regularly confiscated.

6. Turkmenistan

The religious freedom situation in Turkmenistan is similar to that of Tajikistan but worse due to the country’s extraordinary political isolation and government repression. Turkmenistan’s constitution guarantees religious freedom, but many laws, most notably the 2003 religion law, contradict these provisions. All religious organizations must register with the government and remain subject to raids and harassment even if approved. Shiite Muslim groups, Protestant groups and Jehovah’s Witnesses have all had their registration applications denied in recent years. Private worship is forbidden and foreign travel for pilgrimages and religious education are greatly restricted. The government hires and fires clergy, censors religious texts, and fines and imprisons believers for their convictions.

7. Vietnam

Vietnam’s government uses vague national security laws to suppress religious freedom and freedom of expression as a means of maintaining its authority and control. A 2005 decree warns that “abuse” of religious freedom “to undermine the country’s peace, independence, and unity” is illegal and that religious activities must not “negatively affect the cultural traditions of the nation.” Religious diversity is high in Vietnam, with half the population claiming some form of Buddhism and the rest identifying as Catholic, Hoa Hao, Cao Dai, Protestant, Muslim or with other small faith and non-religious communities. Religious groups that register with the government are allowed to grow but are closely monitored by specialized police forces, who employ violence and intimidation to repress unregistered groups.

8. Syria

The ongoing Syrian crisis is now being fought along sectarian lines, greatly diminishing religious freedom in the country. President Bashar al-Assad’s forces, aligned with Hezbollah and Shabiha, have targeted Syria’s majority-Sunni Muslim population with religiously-divisive rhetoric and attacks. Extremist groups on the other side, including al-Qaeda and the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), have targeted Christians and Alawites in their fight for an Islamic state devoid of religious tolerance or diversity. Many Syrians choose their allegiances based on their families’ faith in order to survive. It’s important to note that all human rights, not just religious freedom, are suffering in Syria and in neighboring refugee camps. In quieter times, proselytizing, conversion from Islam and some interfaith marriages are restricted, and all religious groups must officially register with the government.

This article was originally posted on April 30, 2014 at Religion News Service