12 Aug 2020 | News and features

Artists, writers and activists have joined Index and other NGOs in calling on the Scottish government to redraft a proposed new bill.

Rowan Atkinson, Mary “Doll” Nesbit, actor Elaine C Smith, Peter Tatchell and former Scottish Arts Council director Dame Seona Reid have written a joint letter to argue that the wording of the proposed Hate Crime and Public Order (Scotland) Bill while well meaning risks “stifling freedom of expression, and the ability to articulate or criticise religious and other beliefs”.

Organisations including the Humanist Society Scotland and Scottish PEN as well as Index signed the letter.

The letter comes as the Scottish Parliament considers the wording of the bill which the Scottish Government says “provides for the modernising, consolidating and extending of hate crime legislation in Scotland” and will “provide greater clarity, transparency and consistency”.

The signatories to the letter say they welcome the provisions to consolidate existing aggravated hate crimes and the repeal of the blasphemy law. However, they add that the bill as currently drafted “creates a stirring up offence that does not examine the intention behind the action; a crime is committed merely because someone’s words, actions, or artwork might stir up hatred and regardless of their intentions”.

27 Jul 2015 | Academic Freedom, Magazine, mobile, Student Reading Lists

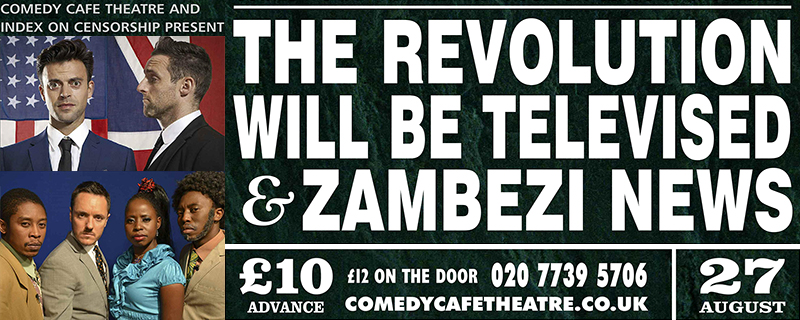

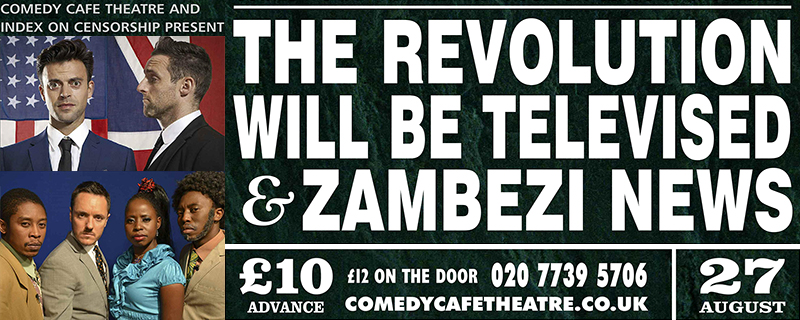

Index on Censorship has had a longstanding interest in the issue of freedom of expression relating to satire. Drawing on Index on Censorship magazine’s more than 40-year-archive, this reading list compiles articles looking at the relationship between comedy and censorship, including a recent piece by Samm Farai Monro aka Comrade Fatso, founder of Zambezi News, Zimbabwe’s leading satirical news programme.

Students and academics can browse the Index magazine archive in thousands of university libraries via Sage Journals.

Comedy and censorship articles

Comedy of Terrors: Zimbabwean satirists challenge power by Samm Farai Monro

Samm Farai Monro, June 2015; vol. 44, 2: pp. 78-82.

Samm Farai Monro, aka Comrade Fatso, talks about founding Zimbabwe’s leading satirical show, and how the nation’s comedians challenge politicians and take on longstanding taboos

Out in Africa by Scott Capurro

Scott Capurro, March 2001; vol. 30, 2: pp. 190-194.

Stand up comedian Scott Capurro explores the limits of stand-up comedy in South Africa

Laughter Lines by Arthur Matthews

Arthur Matthews, March 2015; vol. 44, 1: pp. 86-88.

Co-writer of comedy sitcom, Arthur Matthews discusses censorship in comedy and satire in Ireland

Opiate of the Masses by Saeed Okasha

Saeed Okasha, November 2000; vol. 29, 6: pp. 106-111.

“No matter what form it takes, comedy is a political act in the first degree. It serves as an outlet for frustrations and is a way of putting impossible and incomprehensible situations into perspective. Egyptian society today is urgently in need of such therapy”

Comfort Zones by Scott Capurro

Scott Capurro, November 2000; vol. 29, 6: pp. 134-138.

Stand-up Comedian Capurro provides commentary on how political correctness stifles comedy

South Korea: A Serious Business by Andrew H. Malcolm

Andrew H. Malcolm, July 1978; vol. 7, 4: pp. 62.

A brief look at how comedy was strictly censored in South Korea, as the “serious government has cracked down on humour.”

Side road, dark corner by Edgar Langeveldt

Edgar Langeveldt, November 2000; vol. 29, 6: pp. 86-89.

A stand-up comedian in Zimbabwe describes the dangers comedians face for covering controversial topics, including an account of his own violent attack in 1999.

They shoot comedians by Jamie Garzon

Jamie Garzon, January 2000; vol. 29, 1: pp. 132-133.

Transcripts of television satires by journalist and humourist Jaime Garzon. In August of 1999, Garzon was executed on his way to the Radionet studio.

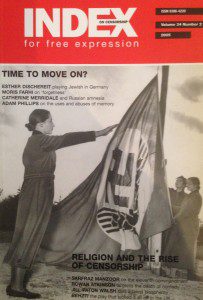

How to Win Friends and Influence an Election by Rowan Atkinson

Rowan Atkinson, May 2005; vol. 34, 2: pp. 117-120.

Atkinson, a foremost British comedian, opposes the government’s proposed law of Incitement of Religious Hatred in a speech given at the House of Lords, as he considers its dire effects on his profession.

Dark Magic by Martin Rowson

Martin Rowson, February 2009; vol. 38, 1: pp. 140-164

Author and cartoonist Martin Rowson expounds on satire, discussing how breaking cultural taboos often stimulates the best political satire

Confronting fear with laughter by Martin Smith

Martin Smith, January 1992; vol. 21, 1: pp. 8-10.

Smith writes about the terror that Burma’s army has inflicted, specifically mentioning the comedian Zargana, who was punished for his bold, pointed jokes.

Comedy is everywhere by Milan Kundera

Milan Kundera , November 1977; vol. 6, 6: pp. 3-7

Banned novelist, playwright, and short story writer Kundera writes on committed literature, the death of the novel, the nature of comedy, and more topics.

“Comedy isn’t here simply to stay docilely in the drawer allotted to comedies, farces and entertainments, where ‘ serious spirits’ would confine it.”

Egypt: Shame on the censor by Karim Alrawi

Karim Alrawi, December 1983; vol. 12, 6: pp. 40..

Discusses the charges filed against the comic actor Said Saleh

“We can only assume that Said Saleh has been made an example of for the shameful act of making people laugh.”

The reading list for comedy and censorship can also be found at the Sage website.

Index on Censorship has been publishing articles on satire by writers across the globe throughout its 43-year history. Prior to our event, Stand Up for Satire, we published a series of archival posts from the magazine on satire and its connection with freedom of expression.

Index on Censorship has been publishing articles on satire by writers across the globe throughout its 43-year history. Prior to our event, Stand Up for Satire, we published a series of archival posts from the magazine on satire and its connection with freedom of expression.

14 July: The power of satirical comedy in Zimbabwe by Samm Farai Monro | 17 July: How to Win Friends and Influence an Election by Rowan Atkinson | 21 July: Comfort Zones by Scott Capurro | 24 July: They shoot comedians by Jamie Garzon | 28 July: Comedy is everywhere by Milan Kundera

17 Jul 2015 | Magazine, mobile

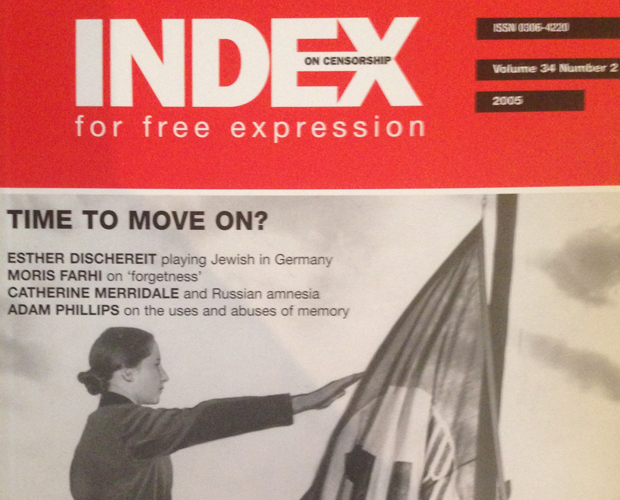

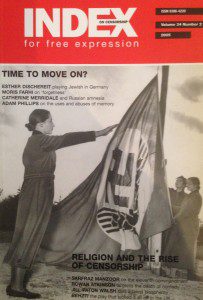

Index on Censorship magazine cover, May 2005

On behalf of all those who make a living from creativity, those whose job it is to analyse, to criticise and to satirise – authors, journalists, academics, actors, politicians and comedians – I oppose the government’s proposed law of Incitement of Religious Hatred. The government claims we need have no concerns about the legislation but as the arguments both for and against the measure have evolved, I have found these reassurances to lack any logic or conviction.

First, there is the government’s belief that the measure will promote racial tolerance. Now racial tolerance may sound a pretty inarguable notion. Unfortunately, what is very arguable is the definition of the term – the definition of a tolerant society. Is a tolerant society one in which you tolerate absurdities, iniquities and injustices simply because they are being perpetrated by or in the name of a religion? Or one where out of a desire not to rock the boat you pass no comment or criticism? Or is a tolerant society one where, in the name of freedom, the tolerance that is promoted is the tolerance of occasionally hearing things you don’t want to hear? Of reading things you don’t want to read? A society in which one is encouraged to question, to criticise and if necessary to ridicule any ideas and ideals, and where the holders of those ideals have an equal right to counter-criticise, to counter-argue and to make their case? That is my idea of a tolerant society: an open and vigorous one, not one that is closed and stifled in some contrived notion of correctness.

I question, also, the ease with which the existing race hatred legislation is going to be extended simply by the scoring out of the word “racial hatred” and the insertion of “racial or religious hatred” as if race and religion are very similar ideas and we can bundle them together in one big lump. It seems clear to me and to most people that race and religion are fundamentally different concepts, requiring completely different treatment under the law. To criticise people for their race is manifestly irrational but to criticise their religion, that is a right. That is a freedom. The freedom to criticise ideas – any ideas – even if they are sincerely held beliefs, is one of the fundamental freedoms of society. A law that attempts to say you can criticise or ridicule ideas as long as they are not religious ideas is a very peculiar law indeed. It promotes the idea that there should be a right not to be offended. Yet in my view, the right to offend is far more important than any right not to be offended simply because one represents openness, the other oppression.

Third, I question the inarguable nature of the phrase “religious hatred” afforded by the use of the highly emotive word “hatred”. So I thought I would modify the name of the proposed measure by changing the terminology while retaining the meaning. The dictionary definition of the word “hatred” is “intense dislike”. Incitement of Religious Intense Dislike. Isn’t it strange how that small change makes it seem a much less desirable or necessary measure? I then found myself asking a strange question. What is wrong with encouraging intense dislike of a religion? Why shouldn’t you do so if the beliefs of that religion or the activities perpetrated in its name deserve to be intensely disliked? What if the teaching or beliefs of the religion are so outmoded, hypocritical and hateful that not expressing criticism of them would be perverse? The government claims that one would be allowed to say what one liked about beliefs because the measure is not intended to defend beliefs but believers. But I don’t see how you can distinguish between them. Beliefs are only invested with life and meaning by believers. If you attack beliefs, you are automatically attacking those who believe the beliefs. You wouldn’t need to criticise the beliefs if no one believed them.

Index on Censorship has been publishing articles on satire by writers across the globe throughout its 43-year history. Ahead of our event, Stand Up for Satire, we published a series of archival posts from the magazine on satire and its connection with freedom of expression.

Index on Censorship has been publishing articles on satire by writers across the globe throughout its 43-year history. Ahead of our event, Stand Up for Satire, we published a series of archival posts from the magazine on satire and its connection with freedom of expression.

14 July: The power of satirical comedy in Zimbabwe by Samm Farai Monro | 17 July: How to Win Friends and Influence an Election by Rowan Atkinson | 21 July: Comfort Zones by Scott Capurro | 24 July: They shoot comedians by Jamie Garzon | 28 July: Comedy is everywhere by Milan Kundera | Student reading lists: Comedy and censorship

I also take issue with the government’s consultation process. After the initial failure to get the law passed in 2001, it engaged in a consultation process involving a House of Lords Select Committee and, I believe, another forum in which it was discussed, to arrive at a new version of the measure that was launched last autumn. What I find extraordinary is that the government is so wedded to the notion that nobody other than the most rabid fascists could possibly fall foul of this legislation that the consultation process didn’t include anyone from the creative community. Many organisations were consulted in the drafting of this legislation: religious organisations, civil liberties groups, law enforcement people; but not one writer, not one journalist, not one academic, not one television producer, theatrical producer; no actor, no comedian; basically nobody whose work might be affected by it. How weird this denial of those concerns, when the incident that most inspired those who have been seeking the introduction of this legislation was the publication of a book. And the most vociferous religious protests we have seen in Britain in the past few months have been against a play and a televised opera. Again, the government will say that these creative works are not the intended targets of this legislation but that raises two issues: first, many religious organisations think they are precisely the target and look forward to wielding their influence to bring prosecutions. If their ambitions are thwarted, there is a high risk of a violent reaction; second, the government is unable to say that creative endeavours could not possibly be targets. And the reason ministers can’t give that degree of reassurance is because creative endeavours clearly could be. Comedy could. Newspaper articles could. Theatrical plays could. The legislation is very simple, very clear and very broad.

The government is relying entirely on the wisdom of the attorney general to protect people like me. It is this discretionary nature of the legislation that is arguably the most disturbing thing about it. It allows the government to rubbish the concerns of the creative community without offering any concrete reassurances other than that the attorney general will look after you. What kind of reassurance is that? The attorney general is not an independent adjudicator. He is an instrument of government: what is politically expedient will be his guide. As the 9/11 attacks on the United States showed, the political agenda in any country can change in a matter of hours. Who’s to say what his priorities are going to be in five days’ time, or five hours’ time, or five years’ time? The government’s belief that legislation on religious hatred will work just as that on racial hatred does is optimistic in the extreme. The pressures in relation to religious hatred are going to be on a completely different scale from that for race: the spread of fundamentalism across a whole range of religions is going to make the issue politically far more highly charged.

And even if I had faith that the attorney general would bail me out in the end, what would I have to go through first? I don’t particularly want to discover that my comedy revue has not, after all, fallen foul of the legislation sitting in an interview room in Paddington Green police station. I would like to know that I could not possibly be put in that situation because of my criticism or ridicule of religious ideas and, by implication, those who follow those ideas. And we now know that even the attorney general’s judgments can be subjected to judicial review. Where would it end?

However, we have to address the issues that have driven the government to their current position. We have to sympathise and empathise with the most conspicuous promoters of this legislation, British Muslims. I appreciate that this measure is an attempt to provide comfort and protection to them but unfortunately it is a wholly inappropriate response far more likely to promote tension between communities than tolerance. The government could have worded the document to tackle a specific issue but chose not to; as a result, those caught in the crossfire are reluctantly going to have to fight to defend intellectual curiosity, the right to criticise ideas, whatever form they take, and the right to ridicule the ridiculous, in whatever context that lies. These ramifications are being denied by the government because it is politically expedient for them to do so, but I personally have been reassured by nothing I have seen, heard or read.

I don’t doubt the sincerity of those who are seeking this legislation but I do question the government’s enthusiasm for it so close to a general election, an enthusiasm that must be rooted in its belief that this measure could help its cause in some marginal constituencies with large religious populations, many of whom are critical of the government’s prosecution of the war in Iraq. It seems a shame we have to be robbed permanently of one of the pillars of freedom of expression because it’s needed temporarily to shore up a wobbling political edifice elsewhere.

Rowan Atkinson is a foremost British comedian and actor. This is the speech he gave in the Moses Room at the House of Lords on 25 January 2005

This article is from the spring 2005 issue of Index on Censorship magazine and is part of a series of articles on satire from the Index on Censorship archives. Subscribe here, or buy a single issue. Every purchase helps fund Index on Censorship’s work around the world. For reproduction rights, please contact Index on Censorship directly, via [email protected]

This article is from the spring 2005 issue of Index on Censorship magazine and is part of a series of articles on satire from the Index on Censorship archives. Subscribe here, or buy a single issue. Every purchase helps fund Index on Censorship’s work around the world. For reproduction rights, please contact Index on Censorship directly, via [email protected]