27 Dec 2021 | Artistic Freedom, Magazine, News and features, United Kingdom, Volume 50.04 Winter 2021, Volume 50.04 Winter 2021 Extras

In June 2015, a national newspaper in Britain started a campaign to have a play banned. This surprised me for two reasons. One: clearly no one had told the Daily Mirror about the Theatre Act 1968, which abolished the state’s censorship of the stage and did away with the quaintly repressive (if that’s not an oxymoron) notion of the Lord Chamberlain’s red pen. Two: the play in question was mine.

I wrote An Audience With Jimmy Savile to show how the late entertainer managed to get away with a lifetime of sexual offending. But despite the play’s very public service intentions, the Mirror started a petition to stop it. And so, for a moment, I found myself in some exalted, unwarranted company: Ibsen and George Bernard Shaw had plays banned (Ghosts and Mrs Warren’s Profession, respectively). Inevitably, however, the Mirror’s cack-handed attempt at censorship failed and the play went ahead.

The episode was instructive, however. Because while it’s true that “we” – that is, the British state – don’t ban plays any more, a powerful and unhealthy censorious reflex still exists and there are clear signs that the urge to stifle and to repress has been growing stronger over the last few years. That repression takes many forms: a social media backlash here, a not-very-subtle government threat there – but it’s real, it’s unhealthy and it’s profoundly worrying.

Censorship in the West is real

We are not, of course, in the same league as China – where a play bemoaning their treatment of Uyghur Muslims, for example, would never be officially sanctioned – but as playwright David Hare told me in an email exchange for this article, censorship in the West is real. It just isn’t called that anymore.

“Is there censorship in the sense that there is censorship in Iran, Russia or China? Of course not. Nobody’s physical survival is threatened,” he said.

But he does seem to say that the BBC has, in effect, become a censorious government’s useful idiot. (My phrase, not his.)

“The BBC has a current policy of deliberately not alienating the government,” he said. “They have chosen the path of ingratiation rather than asserting their independence. The result is, effectively, a range of subjects [which is] hopelessly narrowed. Hence the ubiquity of cop shows. Even medical dramas are forbidden if they stray into questions of ministerial health policy.”

Some might accuse Hare of pique, given that a TV adaptation of his most recent play, Beat the Devil, starring Ralph Fiennes, was turned down by the BBC. He says it was rejected because of the subject matter: Covid-19. (Hare became gravely ill with the virus and the play depicts him on his sickbed, despairing of the government’s response to the pandemic as they “stutter and stumble” on the airwaves.)

Indeed, when Hare went public with his attack on the corporation for turning him down, it refused to comment and the inference was that this was an editorial judgment and not a political one. But, says Hare, they would say that wouldn’t they?

“Censorship in the West,” he said, occurs “in the impossible grey area between editorial judgment and active prohibition.”

He’s right. The most egregious recent example of censorship-in-all-but-name occurred in 2015 when the National Youth Theatre (NYT) cancelled a production of the play Homegrown, about the radicalisation of young Muslims, two weeks before it was due to open. The executive who made the decision cited “editorial judgment” as a factor.

But, thanks to Freedom of Information requests from Index on Censorship, a fuller explanation emerged soon afterwards. An email from the NYT executive responsible for cancelling the production contained the following line: “At the end of the day we are simply ‘pulling a show’ … at a point that still saves us a lot of emotional, financial and critical fallout.”

In other words: “Yes, we might be censoring an important piece of work featuring the two most underrepresented groups on stage – Muslims and young people – because we are worried about defending ourselves from a backlash which hasn’t happened yet, but we don’t really fancy defending free speech and trying to ride out the storm because it’s too much hassle. So, let’s just cancel it and put it down to editorial judgment. Oh yeah – and safeguarding. Even though putting on work like this should be our raison d’etre.”

The director of the piece, Nadia Latif, was understandably shellshocked. A few weeks after the cancellation she said the creative team were “genuinely still reeling. The gesture of someone silencing you is a really profound one. You give your heart and soul to something, and someone comes and shuts it down. It’s like they’re saying my thoughts and feelings are no longer valid.”

And to refer the audience to my earlier point, it’s happening more and more. Albeit behind the scenes, and sometimes in ways you don’t get to hear about. There are two reasons for this: the pandemic and the nature of the current government.

Covid and censorship

The pandemic first. Although Hare’s Covid-19 polemic made it to the stage, that was the exception not the rule. I can’t find any other examples of plays critical of the current government being either staged or commissioned.

That would seem to be directly related to the fact that, during lockdown, every theatre in the country was desperate for financial assistance from the Treasury. So regrettably, but perhaps not surprisingly, few gave the go-ahead to works which bit, or even nibbled, the only hand that could feed them.

This isn’t speculation. When the producers of my play The Last Temptation of Boris Johnson – an unashamed takedown of the prime minister – tried to book it into theatres for a national tour post-pandemic, more than one theatre said, in effect: “We are worried we will lose our Covid grants if we put on a play like that.”

Which brings us on to the current Conservative government and its attempt to take a long march through our cultural, creative and editorial institutions.

When the Tories couldn’t get the former Daily Mail editor Paul Dacre installed as the new boss of the broadcasting regulator Ofcom, they simply scrapped the selection process and ordered that it start again, putting Dacre’s name forward once more – even though, first time round, the selection panel described him as “not appointable”. Dacre has now voluntarily withdrawn and gone back to the Mail.

Someone who was appointable and acceptable, however – to the government, that is – was Nadine Dorries, the new secretary of state for digital, culture, media and sport. Putting Dorries in charge at DCMS was a bit like getting Herod to run the local nursery. Within days of taking over she reportedly started issuing threats against our premier creative organisation – the BBC – which, in her view, was guilty of not sufficiently toeing the line.

After the BBC radio presenter Nick Robinson hectored Johnson in an interview – “Stop talking, prime minister” – it’s said that Dorries told her advisers that Robinson had “cost the BBC a lot of money”.

A bit like the take on Aids policy from the satricial show Brass Eye – is it Good Aids or Bad Aids? – there is Good Censorship and Bad Censorship. The decision to ban Homegrown falls into the latter category.

The social media backlash

But the act of self-editing – in effect, self-censorship – has more going for it. As Hare puts it: “There is all sorts of subject matter I wouldn’t tackle – but entirely because I’m not good enough. I have always refused anything which represents life in Nazi concentration camps, since I don’t trust myself to do it well enough to do justice to what happened. If I don’t think I can do justice to the real suffering of real people, then I avoid, [although] I take my hat off to great writers who are able to expand subject matter at a level where it vindicates the idea of writing about absolutely everything. More power to them.”

But it’s complicated, of course. The worry is that more and more writers, terrified of a vicious social media backlash, are self-editing to an extent that is unhealthy. There are few, for example, who would now dare to pen a play that took a critical, coolly objective look at both sides of the argument over transgender rights – even though tackling difficult subjects and representing “problematic” points of view is, arguably, one of theatre’s prime functions. What could be more relevant, and on point, than a play like that?

One playwright who did sail into these waters was Jo Clifford. Her play, The Gospel According to Jesus, Queen of Heaven, casts Jesus as a trans woman. During its 2018 run at Edinburgh’s Traverse Theatre, an online petition demanding the play be banned garnered a healthy – or rather unhealthy – 24,674 signatures. Soon after that she spoke of how artists and writers were “on the front line of a culture war that will only deepen and strengthen as the ecological and financial crisis worsens and the right feel more fearfully that they are losing their grip on power”.

So, at a time when writers and playwrights need to be bolder, the signs are that they’re becoming more and more cowed; hence Sebastian Faulks’s bizarre announcement that he will no longer physically describe female characters in his novels. Fortunately, most of his peers seem to disagree with him. A recent open letter signed by more than 150 eminent writers, artists and thinkers including JK Rowling, Margaret Atwood and Gloria Steinem warned of “a fear spreading through arts and media”.

“We are already paying the price in greater risk aversion among writers, artists and journalists who fear for their livelihoods if they depart from the consensus, or even lack sufficient zeal in agreement,” it said.

Then again, not everyone agreed with the letter. Author Kaitlyn Greenidge said she was asked to sign it but refused, saying: “I do not subscribe to [its] concerns and do not believe this threat is real. Or at least I do not believe that being asked to consider the history of anti-blackness and white terrorism when writing a piece, after centuries of suppression of any other view in academia, is the equivalent of loss of institutional authority.”

Like I said, it’s complicated.

Promotional material for An Audience With Jimmy Savile. Photo: Boom Ents

The big question for writers, then, is this – if, like me, you believe that anything goes on stage, provided it’s not proscribed by law, how far should you go? Where do the (self-imposed) limits of free expression lie?

Those limits are different for each writer, of course. I would draw the line at, for example, depicting sexual assault on stage. My Jimmy Savile play showed the effects of it, clearly, on the main character – a young woman who’d been abused by him at Stoke Mandeville Hospital – but left the rest to the audience’s imagination. Sometimes it’s more powerful that way.

I would, however, defend the right of other playwrights to go further and include vivid scenes of sexual assault, provided it was for the “right” reasons. There would need to be a coherent dramatic justification for it and the creative team would be advised to have plenty of flak jackets ready. Anyone who tests the boundaries in this way will inevitably face accusations of prurience, unjustified provocation or worse.

The actor’s “thumb”

In 1980, when Howard Brenton showed a scene of homosexual rape in The Romans in Britain, the production found itself being prosecuted for gross indecency by Mary Whitehouse as part of her attempt to “clean up” Britain. (The prosecution failed when a key witness admitted that, from the back of stalls, what he thought was a penis might have been an actor’s thumb.)

A similar court case today would be unlikely. But then again there is always the Court of Public Opinion, powered by the rotten fuel of social media, which is arguably more scary and intimidating than the real thing.

I wouldn’t draw the line at giving free expression on stage to anti-Semitism, either. Sometimes the best way to destroy an argument is to bring it into the light. With one crucial proviso, which I will come to in a moment.

As a Jew who lost relatives in the Holocaust I am fascinated by the subject. I would love to see a play which explained where anti-Semitism came from. Or whether the definitions of it are justified. Are there internal contradictions there? (We fought the war to preserve our freedoms, but isn’t using the label “anti-Semitic” a destruction of one of our most cherished freedoms? As in, the freedom of speech?)

Any play which seeks to answer these questions would need characters espousing anti-Semitism – the more articulately the better, in my view – if they are to work properly.

My proviso would be that the anti-Semitism would need to be both contextualised and rigorously challenged. This could be done within the play – two characters arguing – or in the form of a post-show debate.

I would, for example, even have defended the right of writer Jim Allen and director Ken Loach to stage Perdition, their controversial 1987 play for the Royal Court, despite its disgusting anti-Semitic tropes.

The play accused Jews of “collaborating” with the Nazis during the Holocaust (is there a more loaded, insulting, inappropriate word in this context than “collaborated”?) and was based on the story of Rudolf Kastner, who negotiated with Adolf Eichmann to let more than 1,600 Jews flee Hungary for the safety of Switzerland.

Kastner, it is argued, should have done more to warn more Jews (not just the 1,600 that he rescued) of what was happening. Hence Allen’s line: “To save your hides, you [a Jew] practically led them to the gas chambers.” Disgusting, misjudged and morally wrong.

In the resulting furore, the Royal Court cancelled the play. But the decision to ban it, paradoxically, only increased support for it, and the poison it contained. I would have let it go ahead but tried to persuade Allen to make editorial changes. And if that didn’t work (and I doubt it would have done, although some controversial lines were excised during rehearsals) then I would have staged a debate, forming part of the show, which allowed the Jewish community to explain why the play was so offensive and misjudged. Education beats defenestration, every time.

The stage would be the perfect place to explore the arguments on both sides, but in particular to highlight the muddy thinking of the anti-Israel lobby, as personified by Sally Rooney, who recently decided to punish the Jews by forbidding a Hebrew translation of her latest novel. (Although making them read it might have been a more effective punishment.)

British theatre is not in a good place today. Where are the revolutionaries? The new, angry young men and women, the new John Osbornes? We don’t need to Look Back In Anger: it’s all in front of us, now.

Would a film like 2009’s Four Lions, a deeply moral but, to some, hugely offensive Jihadi satire, get made today? I very much doubt it.

We – all of us: writers, commissioners and directors – need to be braver.

11 Sep 2021 | Afghanistan, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”117433″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]More than 80 leading lights from the worlds of film and theatre have signed an open letter to The Times calling on the British government to give artists, writers and film-makers who remain in Afghanistan and face an uncertain future under the Taliban safe passage out of the country.

The letter, organised by Index on Censorship and Good Chance Theatre, reads as follows: “Over the past two decades, civil society has flourished in Afghanistan with new freedoms ushering in a golden age of art, music, film and writing. At the same time, political dissent and journalism have thrived in a region where free expression is not always respected. With the Taliban takeover of the country, this rich legacy is in imminent peril. We now have a duty to those artists, writers and film makers who will be silenced if we do not act immediately.

“We urge the British government to cooperate with the international community to create a humanitarian corridor for those seeking safe passage out of the country. We also call on those in positions of influence in the creative industries to help those who have escaped to continue their vital work and safeguard the culture of Afghanistan for future generations.“

Signatories

Majid Adin, artist; Riz Ahmed, actor; Jenny Agutter, actor; Alison Balsom, musician; Siddiq Barmak, director; Sanjeev Bhaskar, actor; Hugh Bonneville, actor; Martin Bright, journalist; Barbara Broccoli, producer; Josephine Burton, director; Jez Butterworth, writer; Robert Chandler, poet; Benedict Cumberbatch, actor; Stephen Daldry, director; Catherine Davidson, writer; Amy Davies Dolamore, producer; Ged Doherty, producer; Parwana Fayyaz, poet; Jane Featherstone, producer; Colin Firth, actor; Sonia Friedman, producer; Stephen Fry, actor; Mark Gatiss, actor; Leah Gayer, director; Claire Gilbert, producer; Paul Greengrass, director; Sir David Hare, writer; Zarlasht Halaimzai, writer; Dame Pippa Harris, producer; Afua Hirsch, writer; Nancy Hirst, director; Mike Hodges, director; Sir Nicholas Hytner, director; Sabrina Guinness, producer; Asif Kapadia, director; Mohammad Akbar Karkar, writer; Daniel King, producer; Keira Knightley, actor; Natalia Koliada, producer; David Lan, producer; Jennifer Langer, editor; Stewart Lee, writer; Kerry Michael, director; Krishnendu Majumdar, producer; Mohsen Makhmalbaf, director; Simon McBurney, director; Kate McGrath, director; Sir Ian McKellen, actor; Nada Menzalji, poet; Sir Sam Mendes, director; David Morrissey, actor; Joe Murphy, writer; Zoe Neirizi, poet; Caro Newling, producer; David Nicholls, writer; Amir Nizar Zuabi, director; Sophie Okonedo, actor; Nasrin Parvaz, writer; Pascale Petit, poet; Trevor Phillips, broadcaster; Clare Pollard, poet; Atiq Rahimi, writer; Shirin Razavian, poet; Ian Rickson, director; Clare Robertson, producer; Joe Robertson, writer; Sir Mark Rylance, actor; Philippe Sands QC, writer; Sarah Sands, editor; Tracey Seaward, producer; Shabibi Shah, writer; Rouhi Shafi, writer; Meera Syal, actor; George Szirtes, poet; Dame Kristin Scott Thomas, actor; Elif Shafak, writer; Thea Sharrock, director; Imelda Staunton, actor; Sir Tom Stoppard, writer; Abdul Sulamal, writer; Jawed Taiman, director; Dame Emma Thompson, actor; Orlando von Einsiedel; producer; Emma Watson, actor; Naomi Webb, producer; Samuel West, actor; Krysty Wilson-Cairns, writer; Haidar Yagane, writer; David Yates, director[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

11 Sep 2018 | Artistic Freedom, News and features, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Enough is Enough is a play formed as a gig, tells the stories of real people about sexual violence, through song and dark humour. It is written by Meltem Arikan, directed by Memet Ali Alabora, with music by Maddie Jones, and includes four female cast members who act as members of a band.

For Turkish director and actor Memet Ali Alabora, theatre is about creating an environment in which the audience is encouraged to think, react and reflect. His goal is to leave the audience thinking about and questioning issues, whether it be democracy, free speech, women’s rights or the concept of belonging.

Alabora has always been fascinated by the notion of play and games, even as a child. “I was in a group of friends that imitated each other, told jokes, made fun of things and situations,” he says. The son of actors Mustafa Alabora and Betül Arım, he was exposed early on to the theatre. In high school, Alabora took on roles in plays by Shakespeare and Orhan Veli. He was one of the founders of Garajistanbul, a contemporary performing arts institution in Istanbul.

For Alabora, ludology — the studying of gaming — is not merely about creating different theatrical personalities and presenting them to the audience each time. Rather, it is about creating an alternative to ordinary life — an environment in which actors and members of the audience could meet, intermingle and interact. For those two hours or so, participants are encouraged to think deeply about and reflect upon their own personal stories and the consequences of their actions.

“I think I’m obsessed with the audience. I always think about what is going to happen to the audience at the end of the play: What will they say? What situation do I want to put them in?” the Turkish actor says “It’s not about what messages I want to convey. I want them to put themselves in the middle of everything shown and spoken about, and think about their own responsibility, their own journey and history.”

“It’s not easy to do that for every audience you touch. If I can do that with some of the people in the audience, I think I will be happy,” Alabora adds.

It is this desire to create an environment in which the audience is encouraged to take part, to reflect, to think that Alabora brought to Mi Minör, a Turkish play that premiered in 2012. Written by Turkish playwright Meltem Arıkan, it is set in the fictional country of “Pinima”, where “despite being a democracy, everything is decided by the president”. In opposition to the president is the pianist, who cannot play high notes, such as the Mi note, on her piano because they have been banned. The play encouraged the audience to use their smartphones to interact with each other and influence the outcome.

Alabora explained the production team’s motivation behind the play: “At the time when we were creating Mi Minör, our main motive was to make each and every audience if possible to question themselves. This is very important. The question we asked ourselves was: if we could create a situation in which people could face in one and a half hour, about autocracy, oppression, how would people react?”

The goal wasn’t to “preach the choir” or convey a certain message about the world. It was to encourage the audience not be complacent. “Would the audience stand with the pianist, who advocates free speech and freedom of expression, or would they side with the autocratic president?” Alabora asks.

Alabora considered was how people would react when faced with the same situation in real life. “They were reacting, but was it a sort of reaction where they react, get complacent with it and go back to their ordinary lives, or would they react if they see the same situation in real life?”

On 27 May 2013, a wave of unrest and demonstrations broke out in Gezi Park, Istanbul to protest the urban development plans being carried out there. Over the next few days, violence quickly escalated, with the police using tear gas to suppress peaceful demonstrations. By July 2013, over 8,000 people were injured and five dead.

In the aftermath, Turkish authorities accused Mi Minör of being a rehearsal for the protests. Faced with threats against their lives, Arikan, Alabora and Pinar Ogun, the lead actress, had little choice but to leave the country.

But how could a play that was on for merely five months be a rehearsal for a series of protests that involved more than 7.5 million people in Istanbul alone? “You can’t teach people how to revolt,” Alabora says. “Yes, theatre can change things, be a motive for change, but we’re not living in the beginning of the 20th century or ancient Greece where you can influence day-to-day politics with theatre.”

The three artists relocated to Cardiff, but their experience did not prevent them from continuing with the work they love. They founded Be Aware Productions in January 2015 and their first production, Enough is Enough, written by Arikan, told the stories of women who were victims of domestic violence, rape, incest and sexual abuse. The team organised a month-long tour of more than 20 different locations in Wales.

“In west Wales, we performed in a bar where there was a rugby game right before – there was already an audience watching the game on TV and drinking beer,” Alabora says. “The bar owner gave the tickets to the audience in front and kept the customers who had just seen the rugby game behind.”

“After the play, we had a discussion session and it was as if you were listening to the stories of these four women in a very intimate environment,” he adds. “When you go through something like that, it becomes an experience, which is more than seeing a show.”

After each performance, the team organised a “shout it all out” session, in which members of the audience could discuss the play and share their personal stories with each other. One person said: “Can I say something? Don’t stop what you are doing. You have just reached out one person tonight. That’s a good thing because it strengthened my resolve. Please keep doing that. Because you have given somebody somewhere some hope. You have given me that. You really have.”

Be Aware Productions is now in the process of developing a new project that documents how the production team ended up in Wales and why they chose it as their destination.

“What we did differently with this project was that we did touring rehearsals. We had three weeks of rehearsal in six different parts of Wales. The rehearsals were open to the public, and we had incredible insight from people about the show, about their own stories and about the theme of belonging,” Alabora shares.

Just like Mi Minor and Enough is Enough, the motivation behind this new project is to encourage the audience to think, to reflect on their own personal stories and experiences: “With this new project, I want them to really think personally about what they think or believe and where this sense of belonging is coming from, have they thought about it, and just share their experiences.” [/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner content_placement=”top”][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

Index encourages an environment in which artists and arts organisations can challenge the status quo, speak out on sensitive issues and tackle taboos.

Index currently runs workshops in the UK, publishes case studies about artistic censorship, and has produced guidance for artists on laws related to artistic freedom in England and Wales.

Learn more about our work defending artistic freedom.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1536657340830-d3ce1ff1-7600-4″ taxonomies=”15469″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

22 Apr 2016 | Magazine, Volume 45.01 Spring 2016 Extras

Order your copy of the spring issue of Index on Censorship here.

Saturday 23 April marks the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death. The Bard’s work has long been used to tackle difficult or controversial issues; issues that most often only received an audience due to the cloak of his respectability. To honour the occasion Index has put together a list of all things Shakespeare.

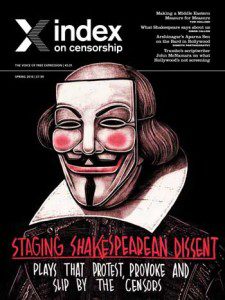

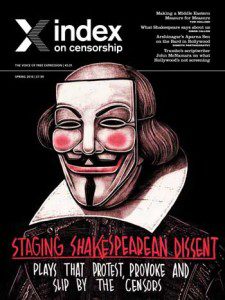

Shakespeare and his role in protest and dissent is the theme of the spring 2016 issue of Index on Censorship magazine: Staging Shakespearean Dissent; Plays That Protest, Provoke and Slip by the Censors. The issue features pieces that explore how the bard’s plays have been used to circumvent censorship and tackle difficult issues around the world; from Bollywood adaptions to Othello in apartheid-era South Africa and a ground-breaking recent performance of Romeo and Juliet between Kosovan and Serbian theatres, along with reports on theatre upsetting people in the USA, and interviews with directors around the world

Index on Censorship magazine editor Rachael Jolley introduces our Shakespeare special issue with her editorial piece, How Shakespeare’s plays smuggle protest. In this piece Jolley discusses how the work of “established” or “historic” playwrights gave actors the chance to tackle themes that would otherwise never be allowed.

Shakespeare was no stranger to censorship, from the Elizabethan to Jacobean police states. In this extract actor and theatre director Simon Callow looks at how his plays amused monarchs and dictators but also prompted their anger.

My Mate Shakespeare recasts the playwright as a brandy loving bingo addict, struggling in a war zone. The poem, which was published in the spring issue of Index on Censorship magazine, was written by poet Edin Suljic following a visit to his home country, Former Yugoslavia. The issue also features an interview with the poet, who fled to London in 1991 ahead of the country’s impending war, discussing his inspiration for the poem and his involvement with theatre group Bards Without Borders.

How well do you know Shakespeare? Take our quiz and see how much you know about the Bard and his work.

The theatre and censorship reading list is a compilation of articles from the magazine archive covering theatre censorship across the world. From the censorship of Romeo and Juliet in US high school textbooks to Janet Suzman’s controversial production of Othello in apartheid-era South Africa, to the banning of performances of Macbeth in actors’ homes in Czechoslovakia.

In an interview with magazine editor Rachael Jolley an award-winning cartoonist, Ben Jennings, discusses his design for the latest Index on Censorship magazine cover on the 400th anniversary of William Shakespeare’s death.

Hitler was a Shakespeare fan; Stalin feared Hamlet; Othello broke ground in apartheid-era South Africa; and Brazil’s current political crisis can be reflected by Julius Caesar. Across the world different Shakespearean plays have different significance and power. In our global guide to using Shakespeare to battle power some of our writers talk about some of the most controversial performances and their consequences.

Order your full-colour print copy of our Shakespeare magazine special here, or take out a digital subscription from anywhere in the world via Exact Editions (just £18* for the year). Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship fight for free expression worldwide.

*Will be charged at local exchange rate outside the UK.

Magazines are also on sale in bookshops, including at the BFI and MagCulture in London as well as on Amazon and iTunes. MagCulture will ship anywhere in the world.