22 Nov 2017 | Mapping Media Freedom, media freedom featured, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”96621″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” alignment=”center”][vc_column_text]Governments have arsenals of weapons to censor information. The worst are well-known: detention, torture, extra-judicial (and sometimes court-sanctioned) killing, surveillance. Though governments also have access to less forceful but still insidious tools, such as website blocking and internet filtering, these aim to cut off the flow of information and advocacy at the source.

Another form of censorship gets limited attention, a kind of quiet repression: the travel ban. It’s the Trump travel ban in reverse, where governments exit rather than entry. They do so not merely to punish the banned but to deny the spread of information about the state of repression and corruption in their home countries.

In recent days I have heard from people around the world subject to such bans. Khadija Ismayilova, a journalist in Azerbaijan who has exposed high-level corruption, has suffered for years under fraudulent legal cases brought against her, including time in prison. The government now forbids her to travel. As she put it last year: “Corrupt officials of Azerbaijan, predators of the press and human rights are still allowed in high-level forums in democracies and able to speak about values, which they destroy in their own – our own country.”

Zunar, a well-known cartoonist who has long pilloried the leaders of Malaysia, has been subject to a travel ban since mid-2016, while also facing sedition charges for the content of his sharply dissenting art. While awaiting his preposterous trial, which could leave him with years in prison, he has missed exhibitions, public forums, high-profile talks. As he told me, the ban directly undermines his ability to network, share ideas, and build financial support.

Ismayilova and Zunar are not alone. India has imposed a travel ban against the coordinator of a civil society coalition in Kashmir because of “anti-India activities” which, the government alleges, are meant to cause youth to resort to violent protest. Turkey has aggressively confiscated passports to target journalists, academics, civil servants, and school teachers. China has barred a women’s human rights defender from travelling outside even her town in Tibet.

Bahrain confiscated the passport of one activist who, upon her return from a Human Rights Council meeting in Geneva, was accused by officials of “false statements” about Bahrain. The United Arab Emirates has held Ahmed Mansoor, a leading human rights defender and blogger and familiar to those in the UN human rights system, incommunicado for nearly this entire year. The government banned him from travelling for years based on his advocacy for democratic reform.

Few governments, apart from Turkey perhaps, can compete with Egypt on this front. I asked Gamal Eid, subject to a travel ban by Egyptian authorities since February of 2016, how it affects his life and work? Eid, one of the leading human rights defenders in the Middle East and the founder of the Arab Network for Human Rights Information (ANHRI), has seen his organisation’s website shut down, public libraries he founded (with human rights award money!) forcibly closed, and his bank accounts frozen.

While Eid is recognised internationally for his commitment to human rights, the government accuses him of raising philanthropic funds for ANHRI “to implement a foreign agenda aimed at inciting public opinion against State institutions and promoting allegations in international forums that freedoms are restricted by the country’s legislative system.” He has been separated from his wife and daughter, who fled Egypt in the face of government threats. The ban forced him to close legal offices in Morocco and Tunisia, where he provided defence to journalists, and he lost his green card to work in the United States. He recognises that his situation does not involve the kind of torture or detention that characterises Egypt’s approach to opposition, but the ban has ruined his ability to make a living and to support human rights not just in Egypt but across the Arab world.

Eid is not alone in his country. He estimates that Egypt has placed approximately 500 of its nationals under a travel ban, about sixteen of whom are human rights activists. One of them is the prominent researcher and activist, Hossam Bahgat, founder of the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights, who faces accusations similar to Eid’s.

Travel bans signal weakness, limited confidence in the power of a government’s arguments, perhaps even a public but quiet concession that, “yes indeed, we repress truth in our country”. While not nearly as painful as the physical weapons of censorship, they undermine global knowledge and debate. They exclude activists and journalists from the kind of training that makes their work more rigorous, accurate, and effective. They also interfere in a direct way with every person’s human right to “leave any country, including one’s own,” unless necessary for reasons such as national security or public order.

All governments that care about human rights should not allow the travel ban to continue to be the silent weapon of censorship – and not just for the sake of Khadija, Zunar, and Gamal, but for those who benefit from their critical voices and work. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Mapping Media Freedom” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-times-circle” color=”black” background_style=”rounded” size=”xl” align=”right”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

Since 24 May 2014, Mapping Media Freedom’s team of correspondents and partners have recorded and verified 3,597 violations against journalists and media outlets.

Index campaigns to protect journalists and media freedom. You can help us by submitting reports to Mapping Media Freedom.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Don’t lose your voice. Stay informed.” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship is a nonprofit that campaigns for and defends free expression worldwide. We publish work by censored writers and artists, promote debate, and monitor threats to free speech. We believe that everyone should be free to express themselves without fear of harm or persecution – no matter what their views.

Join our mailing list (or follow us on Twitter or Facebook) and we’ll send you our weekly newsletter about our activities defending free speech. We won’t share your personal information with anyone outside Index.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][gravityform id=”20″ title=”false” description=”false” ajax=”false”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row]

1 Sep 2015 | mobile, News and features, Turkey, United Kingdom

The anti-terror charges against reporters for Vice News in Turkey are not isolated. In recent years, a number of countries have used broad anti-terror laws to restrict the freedom of the press.

Turkey

British journalists Jake Hanrahan, left, and Philip Pendlebury and Iraqi translator and journalist Mohammed Ismael Rasool were filming clashes between pro-Kurdish youths and security forces, according to Vice. (Photos: Vice News)

Two British journalists and a local fixer working for Vice News were charged on Monday 31 August in Turkey with “working on behalf of a terrorist organisation”. They will remain in detention until their trial, the date of which has not yet been announced.

The journalists Jake Hanrahan, Philip Pendlebury and Iraqi translator and journalist Mohammed Ismael Rasool were filming clashes between security forces and youth members of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) in the south-eastern city of Diyarbakir on Thursday when they were arrested.

Turkey’s broad definition of terrorism means that any journalist reporting on PKK activities or Kurdish rights can be charged with the offence of making “terrorist propaganda” and jailed.

Index on Censorship Chief Executive Jodie Ginsberg said: “Coming just days after the unjust sentencing of three Al Jazeera journalists in Egypt, these latest detentions of journalists simply for doing their jobs underlines the way in which governments everywhere can use terror legislation to prevent the media from operating.”

Egypt

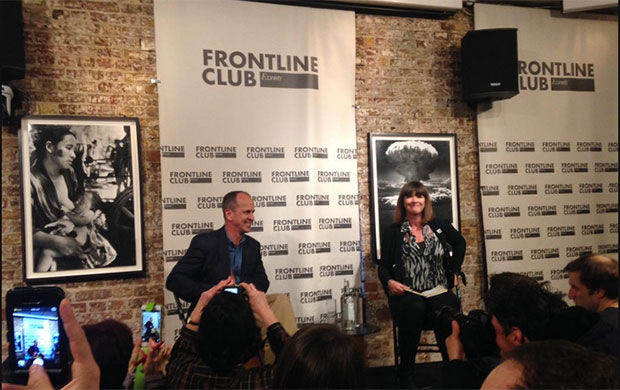

Peter Greste spoke to a Frontline Club audience about his arrest and detention in Egypt. (Photo: Milana Knezevic / Index on Censorship)

Egypt remains a cause for concern when it comes to press freedom: on 29 August 2015 Al Jazeera journalists Mohamed Fahmy, Peter Greste and Baher Mohamed were sentenced to three years in prison. The journalists were found guilty of of “broadcasting false information” and “aiding a terrorist organisation” – a reference to the Muslim Brotherhood.

The sentencing came just weeks after President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi’s government passed an anti-terror law setting a fine of up to 500,000 Egyptian pounds (£41,600) for journalists who stray from government statements or spread “false” reports on attacks or security operations against armed fighters.

Jordan

Jordan introduced a new “anti-terror” law in 2006 prohibiting, among other things, the engagement in “acts that expose the kingdom to risk of hostile acts, disturb its relations with a foreign state, or expose Jordanians to acts of retaliation against them or their money”. The charge carries a prison sentence of three to 20 years. The law was amended in 2014 to , broaden the definition of terrorism.

Interpretation of the law has been varied. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), in April 2015 a journalist was jailed for criticising the Saudi-led bombing of Houthi forces in Yemen. Another journalist was detained in July 2015 for breaking a recent ban on coverage of a terror plot. Earlier in 2015, an activist who criticised the royal family’s support of Charlie Hebdo on Facebook was sentenced to five months in jail under the anti-terror law.

Tunisia

One month after June’s terrorist attack on Sousse beach killing 38 tourists, for which ISIS claimed responsibility, Tunisia approved new anti-terror legislation.

Under the legislation, website editor Nour Edine Mbarki was charged in connection with publishing a photograph of a car that purportedly transported a gunman behind the beach attack. According to the CPJ, he was charged under Article 18 of the law with “complicity in a terrorist attack and facilitating the escape of terrorists,” which carries a prison term of between five and 12 years. He is currently awaiting a trial date.

Human Rights Watch said the new anti-terror bill “would open the way to prosecuting political dissent as terrorism, give judges overly broad powers, and curtail lawyers’ ability to provide an effective defence”.

Pakistan

Rights groups have long criticised Pakistan’s notorious anti-blasphemy laws for their effect on freedom of expression in the country. But strengthened anti terror legislation is also impacting the way journalists operate in the country.

In June, three Pakistani journalists were charged under the Anti-Terrorism Act, reportedly for covering the activities of a dissident politician, according to the Pakistan Press Foundation. A year before, a TV anchor was also charged under the law.

One to watch: Kenya

Following two separate attacks by al-Shabab militants in December, Kenya’s President Uhuru Kenyatta signed into law a new security bill that could curtail press freedom. Under the new law, journalists could face up to three years in jail if their reports “undermine investigations or security operations relating to terrorism” – or even if they published images of “terror victims” without police permission.

This hasn’t come into play yet – in February, the Kenyan High Court threw out several clauses, including those that could impact media freedom. The government has said it would consider lodging an appeal.

This post was written by Emily Wight for Index on Censorship

This article was posted on 1 September 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

19 Sep 2014 | Events, Tunisia

Index on Censorship in association with Article 19, Tunisia, invite you to a workshop to launch Frontline Freespeech, a pilot project seeking to amplify the voice of individuals under pressure.

This workshop will bring together grassroots activists alongside leading free expression campaigners to share their recent experiences of censorship, to record and map current censorship challenges and to build impactful free speech networks in Tunisia.

A wide audience are expected to attend the workshop:campaigners, community leaders, network co-ordinators, human rights defenders, journalists, bloggers, artists, scholars and representatives of minority groups facing free expression challenges alongside key human rights organisations and independent media.

Tuesday 30 September 2014

Golden Tulip El Mechtel 3 Avenue Ouled

Haffouz | El Omrane, Tunis – Tunisia

To RSVP for this workshop please email Amira Cherif, [email protected], +21652479557

Registration will close on Tuesday 23 September 2014 | PDF

8 Jul 2014 | Egypt, News and features

A still from the trailer of big-budget Egyptian film Yacoubian Building (Image: Strand Releasing/YouTube)

When mass protests broke out in Egypt on January 25 2011, the uprising took many people around the world, including Egyptians, by surprise. But some believe the stage was in fact already being set for revolution years earlier — and that popular culture played a part.

On 17 December 2010, Mohamed Bou Azizi, a Tunisian street vendor had set himself on fire in protest of the confiscation of his wares and the humiliation inflicted on him by a municipal official. His act sparked mass street protests in Tunisia which 28 days later, led to the overthrow of the authoritarian regime of Zine El Abidine Ben Ali.

When Ben Ali fell, analysts questioned whether the uprising in Tunisia would inspire similar revolts in other North African countries with despotic regimes, including Egypt which they pointed out, also suffered enormous socio-economic inequalities, widespread youth unemployment and political marginalisation of the masses.

The thought of a mass uprising in Egypt was however, quickly dismissed by Egyptian officials as “outrageous”.

“Egypt is not Tunisia”, scoffed veteran diplomat Amr Moussa when I asked him if Egypt would be next. I met Moussa on January 19, 2011 at a Sharm El Sheikh conference on Arab Economic Integration — a gathering that was overshadowed by the dramatic events unfolding in Tunisia. The veteran diplomat who had served as foreign minister under Hosni Mubarak, confidently told me that Egypt was “a much bigger country and vastly different in terms of demography”. Moussa’s argument convinced me. Indeed, Tunisia is a homogeneous society with a relatively well-educated population unlike Egypt — a more diverse society with in excess of 16 million illiterate people, according to a 2012 study released by the Central Agency for Public Mobilisation and Statistics.

Besides, there was widespread political apathy in Egypt. For decades, the Egyptian people had silently tolerated rights abuses at the hands of the corrupt regime. So patient were the Egyptians with their repressive government that analyst Khaled Diab joked about their political apathy in an op-ed published in the Guardian in June 2009, saying that: “The people of Egypt possessed some sort of a cultural gene against rebellion and risk taking.”

It was not surprising that the Egyptians had shown remarkable immunity to the Tehran protest virus, he wrote, explaining that “the Egyptian people had for decades, been ruled by a long succession of foreigners who cared little for their well being. They considered their native rulers just as alien.”

The widely-anticipated political pandemic had hitherto, failed to materialise… Until Tunisians revolted.

But contrary to popular belief, the eighteen-day uprising that overthrew Mubarak was not an “overnight eruption”. In fact, it had taken several years of ground-laying and a series of events helped pave the way for the revolt that was to come.

Some analysts believe the stage was being set for the 2011 mass protests from as early as 2004, not long after the fall of Iraqi strongman Saddam Hussein.

This was the year Egyptian intellectuals, artists and activists founded the Kefayya (Enough) Movement that would oppose the Mubarak regime and call for fundamental constitutional and economic reforms. Although the overarching ideology of the movement is largely secular, many members of the then-outlawed but tolerated Muslim Brotherhood joined forces with the leftists and secularists.

Moreover, there were the workers’ unions, which in the years leading up to the uprising had organised a series of labour strikes, protesting low wages and rising food costs. The 2008 labour protests which began as an initiative of workers in the textile industry in Mehalla El Kobra and other Egyptian cities, inspired mass momentum and were the first spark that ignited the street protests that followed two years later.

Egypt’s pro-democracy youth activists were also active and widely credited for using social media networks to fuel the anger against the brutal regime. The April 6 Youth Movement and “We are All Khaled Said” Facebook group mobilised Egyptians for the protests by posting videos of police brutality and calling for civil disobedience.

Again, contrary to popular belief, the January 2011 uprising was not merely a “people’s movement”, as it has often been described. Some analysts think the uprising may have been driven by the security state much like the revolt that ousted Mohamed Morsi, Egypt’s first freely elected president, two years later. Breakaway members of Tamarod, the movement that last summer gathered signatures for a petition calling on the Islamist president to step down, later revealed that “state security agents had guided and influenced our campaign”.

Some members of the group went as far as admitting that “some of the movement’s founders had been planted by state security” according to a Reuters article published online on February 20, 2014. Similarly, the January 25 uprising may have also been guided, albeit more subtly by the deep state — a term used to refer to the country’s combined security apparatus: the intelligence services, the police and National Security. It was no secret that Mubarak had been grooming his son Gamal to succeed him — a move that was rejected by senior-ranking generals in the army. The generals had expected the succession bid to cause popular unrest and decided to be prepared to step in.

“General Abdel Fattah El Sisi, who was head of military intelligence in 2010, had already been picked by his bosses as the country’s next defence minister and was asked to prepare a study of Egypt’s political future. He proposed that the army should be prepared to move in to ensure stability and preserve its central role in the state in the likely event of civic unrest breaking out,” journalist Richard Spencer wrote in an opinion piece published in the Telegraph in June 2014. Political analyst Hassan Nafaa was quoted as telling Spencer that: “When the revolution of 2011 exploded, the army had already made plans to deploy.”

“They chose to sacrifice Mubarak rather than the regime itself,” Nafaa added.

Egypt’s powerful military firmly believes it is entitled to remain in power, having fought two wars with Israel. Besides, at stake — should the country be ruled by a civilian president — is the military’s vast business empire estimated to be as much as 40 percent of the country’s GDP.

So how did the deep state in Egypt prepare unsuspecting Egyptians for the uprising that was to come?

Culture and the arts served as the catalysts for the movement for change that was being shaped as early as four or five years before the actual “revolution” erupted. From 2006 onwards many artistic works, including locally-produced films screened in Egyptian theatres, helped fuel the people’s anger and frustration, inciting protests against the inept government. While some may dismiss this theory as absurd, in reality, there is strong evidence to support it.

Take the big-budget film “Yacoubian Building”, based on the novel of the same name by author Alaa Aswany, a member of the opposition Kefayya Movement. The three hour epic, screened in Egypt in 2006, shed the spotlight on a host of societal ills including the rampant corruption, sexual repression and religious fundamentalism plaguing contemporary Egyptian society. It also reflected the hopes of young Egyptians for a just society based on rule of law and respect for civil liberties. Like Egypt itself, the building in which the film’s lead characters reside had crumbled “from a once-elegant edifice of Art-Deco splendour now slowly decaying in the smog and bustle of downtown Cairo”, Nana Asfour, who works as a cultural editor for the New Yorker, wrote in a 2007 review of the book.

The book brings to life “a seedy and despicable Cairo where only the corrupted and corruptible can fare well” she wrote, adding that “in this scathing critique of contemporary Egyptian society, one is hard put to find a redeemable character”.

From Abdou and Busayna, who by necessity acquiesce to selling their bodies to feed their families, to Talal, who seeks solace in religion and later resorts to “martyrdom” — they all are victims of their merciless society. The film also portrays the fake religiosity widespread in today’s Egypt where many conceal their greed behind deceiving pious behaviour and appearances — like prominent lawyer Kamal El Fouli who rigs the parliamentary vote in favour of Hag Azzam, justifying the action as “implementation of God’s will”.

“Our Lord created the Egyptians to accept authority,” El Fouli tells Azzam in the film.

Shocking as it was to an audience previously unaccustomed to having the realities of their everyday lives mirrored so brazenly, the Yacoubian Building was a wake-up call to many Egyptians who were able to identify with the film’s characters. It was also the first in a series of films produced between 2005 and 2010 that were fiercely critical of society and which spurred Egyptians to rebel against the flagrant injustices within it.

Heya Fawda (“It’s Chaos”), an Egyptian-French 2007 co-production and the last film by internationally-acclaimed Egyptian director Youssef Shahin, meanwhile brought international attention to Egypt’s longstanding problem of police corruption and brutality when it was screened at that year’s Venice Film Festival. Police brutality was one of the main causes that triggered the 2011 uprising which aptly coincided with the country’s National Police Day. Set in Cairo’s populous district of Shoubra, the film shockingly depicts the brutal actions of a shady police officer, feared and loathed by the residents in his neighbourhood. So shocking was his brutality that it prompted some film critics to question whether the film was “serious or a lampoon”.

Khaled Youssef, who co-directed the film with Shahin, was later credited with having had the vision to foresee the coming political changes and for “stirring the still waters” with his films. The filmmaker and scriptwriter, who joined the pro-democracy activists in Tahrir Square during the 2011 uprising, would later reveal himself as a fierce opponent of the democratically elected Muslim Brotherhood regime, aligning himself closely with the military-backed authorities that replaced the ousted Morsi. His close links with the military have raised questions over whether his films were actually the outcome of his foresight or a premeditated and carefully calculated plan by the country’s security apparatus to topple Mubarak.

Youssef’s follow-up to Heya Fawda was another shocking revelation of the flagrant social injustice prevalent in modern-day Egyptian society. Set in a Cairo slum area, it depicts the daily struggles of the inhabitants of this deprived neighbourhood, including sexual violence against women and the plight of street children. The film ends with the residents of the slum rising up in arms to protest their conditions — which some observers viewed as a possible beckoning call on needy Egyptians to rise in similar fashion.

Last but not least, was the 90 minute comedy “The President’s Chef” released in 2010. In the film, a simple cook tries to convey to a president out of touch with his people, the hardships faced by average Egyptians in their daily lives. Film critics drew similarities between the film’s lead character and the real president who during the last ten years of his rule, had often been criticized for isolating himself in his own ivory tower, oblivious to the needs of his people.

In a country with a long tradition of strict censorship rules, one cannot help but wonder if the censors’ decision to pass those films was a coincidental loosening up of their tight restrictions in a bid to give a semblance of democracy and free speech. Or was it instead, a deliberate and tactical scheme to pave the way for Mubarak’s ouster?

Looking back at the events of the last three years that have ended with the return of the old regime minus Mubarak, it appears clear that nothing in Egypt happens by sheer coincidence.

This article was posted on 7 July 2014 at indexoncensorship.org