24 Oct 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, News, Turkey

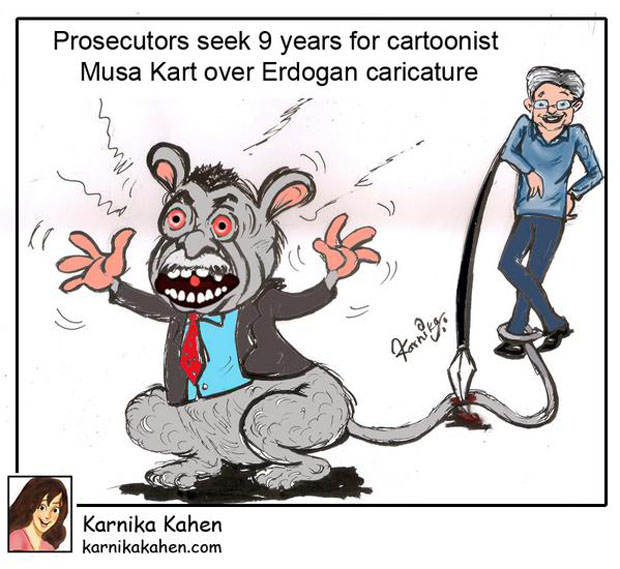

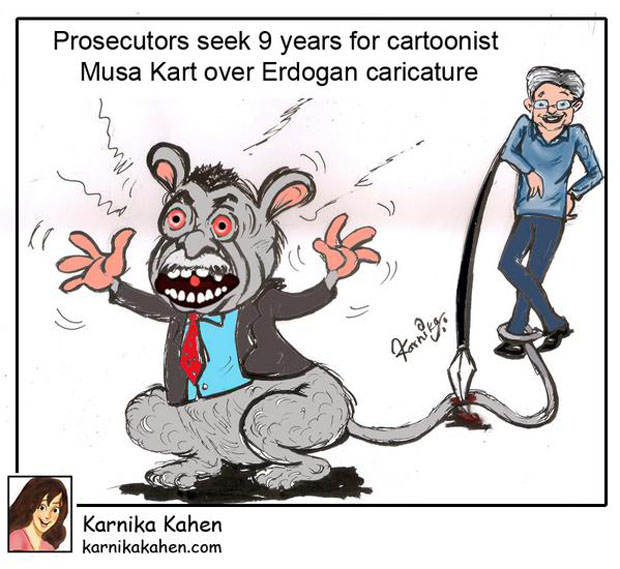

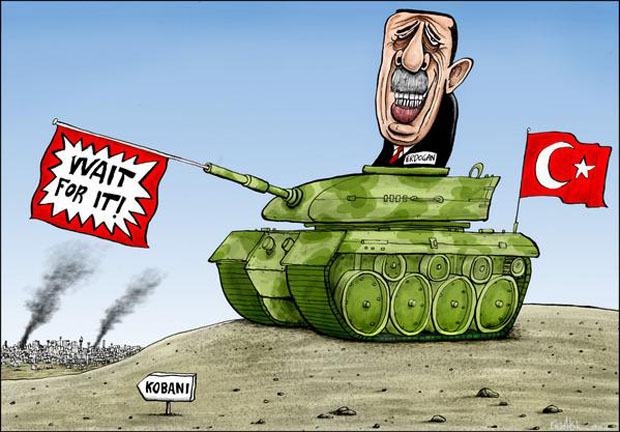

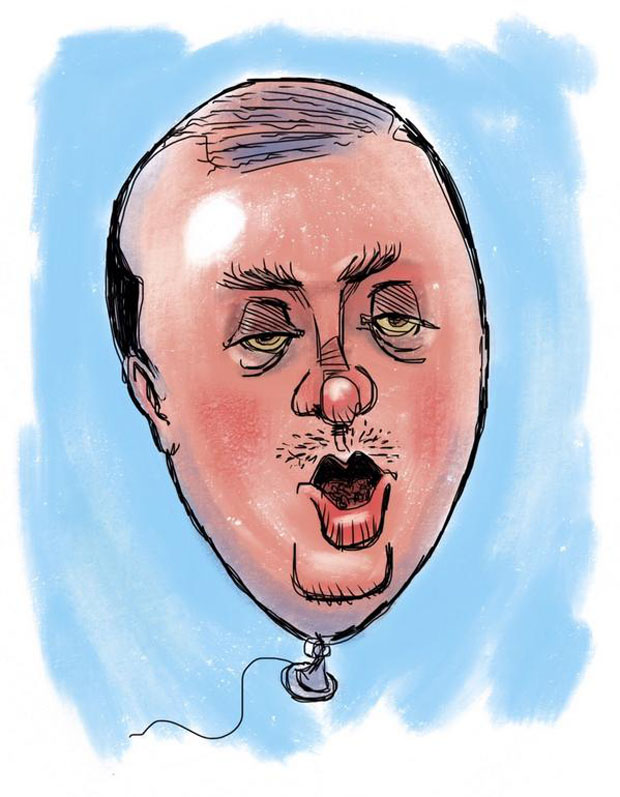

When Turkish political cartoonist Musa Kart faced nine years in prison for “insulting” President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, his colleagues from across the world fought back in the best way they know how — by drawing their own #erdogancaricature.

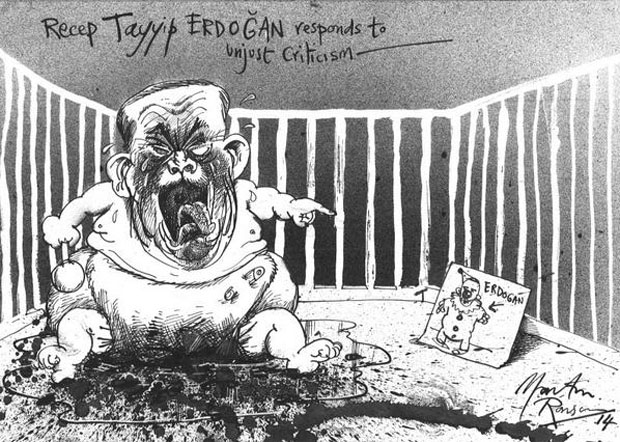

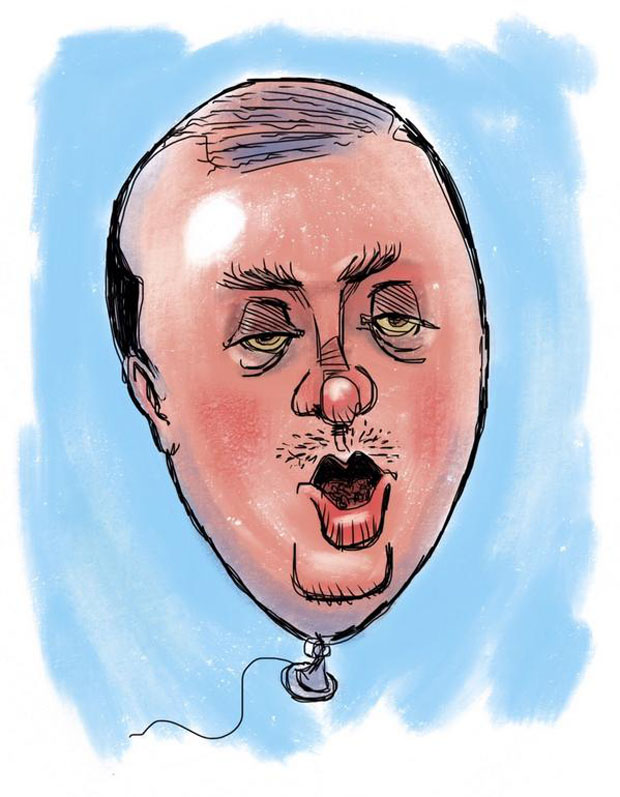

By: Martin Rowson

The online campaign was started on Thursday by Martin Rowson, cartoonist for The Guardian, The Independent and Index on Censorship among others, as Kart was scheduled to appear in court.

Erdogan himself filed the complaint against Kart over a cartoon published in the daily Cumhuriyet on 1 February 2014 showing the then prime minister as a hologram watching over a robbery. This was a reference to his alleged involvement covering up a high-profile graft scandal.

Erdogan claimed Kart was guilty of “insulting through publication and slander,” reports Today Zaman. And while the court initially ruled that there were no legal grounds for action, this decision was revoked following complaints from Erdogan’s lawyer. Kart was also fined in 2005 for drawing Erdogan as a cat.

In court on Thursday, Kart stated: “Yes, I drew it [the cartoon] but I did not mean to insult. I just wanted to show the facts. Indeed, I think that we are inside a cartoon right now. Because I am in the suspect’s seat while charges were dropped against all the suspects [involved in two major graft scandals]. I need to say that this is funny.”

He was finally acquitted, but many of his fellow cartoonists has already shared their artistic interpretations of Erdogan and the case.

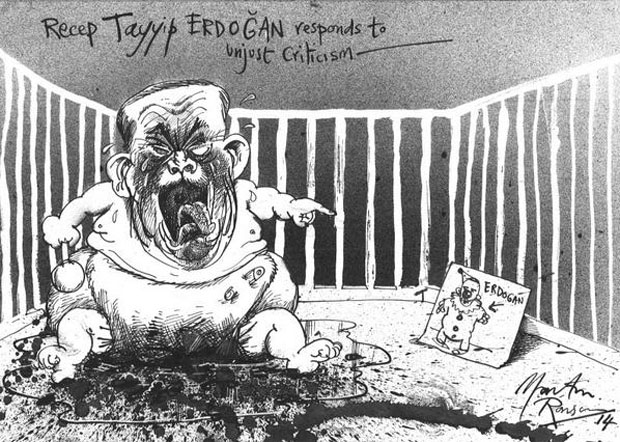

By: Morten Morland

By: Ben Jennings

“I was alerted to Musa Kart’s plight by the excellent Cartoonists’ Rights Network International (CRNI) and previously, when an Iranian cartoonist was sentenced to 40 lashes, a bunch of us got together to draw the offended politician who’d had him arrested, the sentence was commuted,” Martin Rowson told Index via email.

By: Steve Bright

By: Kanika Mishra

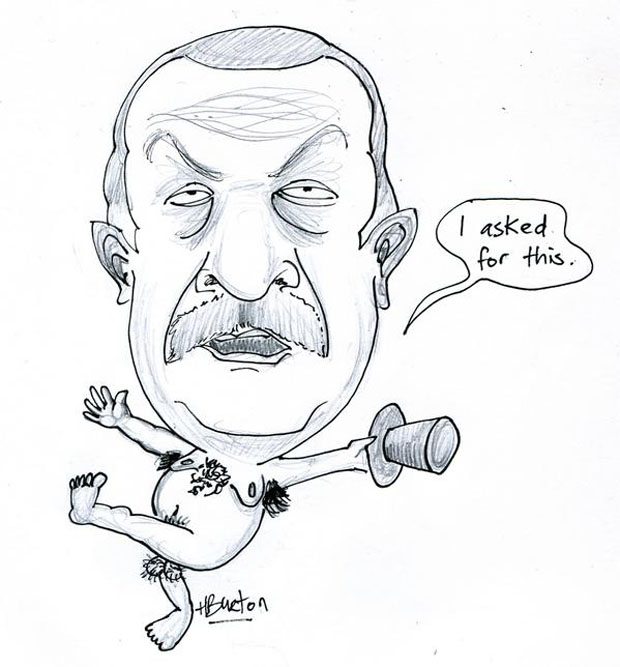

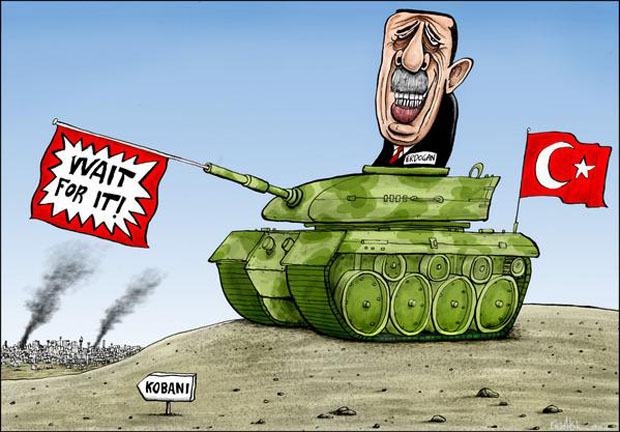

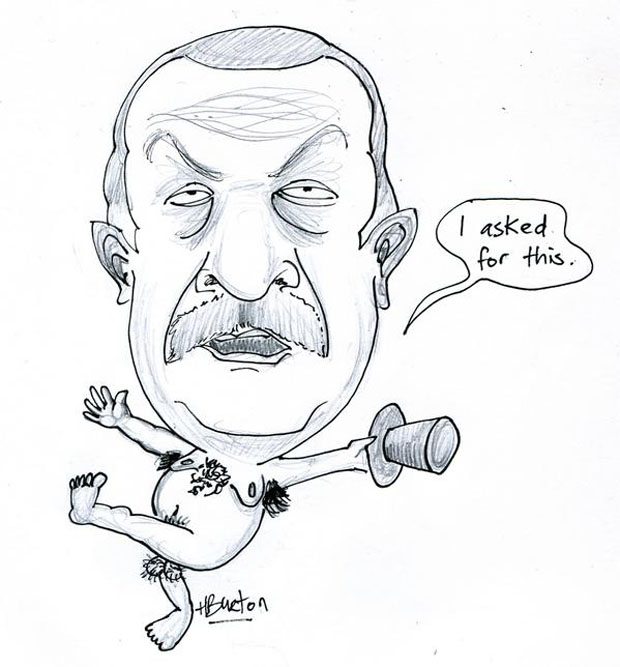

“It seems this kind of international bullying by cartoon does have an effect, as even the chippiest despot out there can usually detect a batsqueak of the shamefulness of not being able to take a joke. In Musa Kart’s case, the threat of up to nine years in prison was such an outrageous abuse of power I didn’t wait for anyone else to organise this and simply put out a call via Twitter for cartoons of Erdogan to show solidarity. No idea if it had any effect on the court (I doubt it) though it may put Erdogan off the idea of taking the case to a higher court. I hope so. And I hope it gave Musa Kart a feeling that he wasn’t on his own in there. Basically, this is cartoonists playing the Spartacus card, because if one of us, anywhere, is persecuted for laughing at power, we all are,” said Rowson.

By: Harry Burton

By: Brian Adcock

“Cartoonists are often the last bastion of free speech in repressive regimes and equally valued for telling the truth as it is, in democratic societies too; some consider their work to be of just as much value, if not more, as journalists, and many respected for the courage and ability to often say and report what others cannot, or fear to do, alongside the just as valued use of satire to reveal a truth which otherwise might not see the light of day,” Patricia Bargh from CRNI explained to Index in an email.

By: Mike Roberts

By: Tjeerd Royaards

“Thus as societies we should value and protect their right to do what they do, and if they know there is an organisation out there who will take up their case, should they be targeted, we hope that gives them the confidence to continue to on and assists them in their valuable work too,” Bargh added.

This article was originally posted on 20 October at indexoncensorship.org

24 Sep 2014 | Digital Freedom, Mapping Media Freedom, News, Turkey

Former Turkish Prime Minister and current president Recep Tayyip Erdogan spoke to tens of thousands of supporters during a presidential campaign rally in Istanbul in early August. (Avni Kantan / Demotix)

Seven months after a previous amendment was introduced to Turkey’s contentious 5651 law governing internet activity, new restrictions were passed late on September 8. Before the February amendments were signed into law by then President Abdullah Gül, a protracted approval process over the course of a few weeks helped bring attention to the proposals. In contrast to the online and street protests against internet censorship that preceded the amendments’ approval earlier this year, last week’s changes to the 5651 law were rushed through a vote before word could spread about them.

The newest restrictions are only two articles tucked into a lengthy omnibus reform bill: in a total of seven sentences, amendments number 126 and 127—part of a list of 146—succinctly make way for invasive data logging and the speedier blocking of access to websites. Nihan Güneli, an Istanbul-based technology and media lawyer, said the hurried vote on the bill kept opposition to the internet regulations muffled. When the details of the earlier 5651 amendments were first presented in January, Güneli said, “everybody was protesting it. I believe that was one of the main reasons Abdullah Gül rejected these two main articles. But this time we didn’t have any time. We just saw the article and everybody was shocked.”

Before approving the last amendments in February, Gül urged legislators to adjust two of its articles: one measure allowing for Turkey’s Telecommunications Directorate (TİB) to block access to some websites within four hours – without a court order, was changed to require judicial review. Another measure that gave TİB the right to collect internet users’ data was changed to restrict access to user logs.

Former Prime Minister Erdogan replaced Gül as Turkey’s new president on August 28. Less than two weeks after his inauguration, these newest internet restrictions allow for websites to be blocked within four hours if their content is ruled a threat to national security or public order, or if restricting access to them can prevent a crime. Under the new amendment, TİB is also allowed to store internet users’ traffic logs and metadata. In an attempt to make the February bill amendable to critics, these two most offensive parts of the previous amendments to 5651 were dropped at Gül’s request. Now exactly those measures have been quietly put into effect under Turkey’s new president.

The targeting of websites determined to be threats to national security comes after the Turkish government struggled to suppress a series of leaked phone recordings earlier this year that spread on social media. The wiretapped phone conversations featured what appeared to be the voices of Prime Minister Erdogan and people close to him, and pointed to their implication in an ongoing corruption scandal. Other recordings ostensibly showed Erdogan’s meddling in the judiciary and with owners of major media outlets. In March, a leaked recording from a meeting at Turkey’s foreign ministry detailed the government’s considerations for military involvement in Syria. Shortly after that recording was posted on YouTube, access to the platform was blocked entirely in Turkey.

YouTube is one prominent example of access restrictions prior to the most recent legislation reform—the website was previously banned for over two years up until 2010. The possible effects of the newest amendments’ measures for blocking websites are still unclear, although the implications for access to information are startling. A number of small, alternative news websites have been aggressively covering the Turkish government’s recent corruption scandal. With no offline distribution form, their livelihood would be put at risk if their websites became inaccessible.

The news website Diken was founded in January 2014 and has since gained a following for its alternative reporting. In June, Diken was named “internet newspaper of the year” by an environmental organisation. Editor in chief Erdal Güven says Diken published almost every one of the leaked government phone recordings earlier this year. So far, Diken has not been shut down or admonished by authorities, which Güven suggests may be because the website is still less than one year old and may not be considered a sufficient threat. Diken risks being targeted by TİB at any point, though, says Güven. “It depends on an advisor to a minister, an MP, the president. Just to read a story of ours and then complain to the legal authorities,” Güven said. Referring to the fines media companies can face for publishing information deemed illegal, Güven added, “They can ask us to pay a huge amount of money. We don’t know what they will do. We don’t have a huge amount of money, we have a tight budget. Of course this would affect us.”

Because of their editorial choices and coverage of government scandals, alternative news sources and social media are the main targets of the new restrictions on website access. Elif Örnek, a reporter for the leftist newspaper soL, says that journalists are often pressured or face censorship, and in reporting on issues that the government is trying to suppress, like the leaked phone recordings, the stakes can be especially high for the media. “The main thing is that when you’re thinking about the public interest, there are some dangers you have to risk,” Örnek said.

For internet users, TİB’s broad collection of metadata is a newly legal tool for monitoring online activity. Nihan Güneli says it’s impossible to predict how TİB will purpose users’ traffic logs. “Within six months, maybe we’ll hear about a case, maybe somebody will be arrested or someone committed a crime and we’ll see this traffic information in court. Then we’ll know what they’re doing with it,” Güneli said. Censorship of websites within Turkey is not new, making it hard to predict whether the new bill’s other article, which gives TİB the authority to block sites within four hours, will have palpable effects on access to information. “TİB has power right now and nobody knows what they’re going to do with it. I don’t think they know either,” Güneli said.

Media violation reports from Turkey via mediafreedom.ushahidi.com

Twitter account of Today’s Zaman editor faces closure

Habertürk fires reporter

Journalist kidnapped and released by PKK

Report shows media use of hate speech increased in early 2014

Several media organisations denied accreditation to AK Party congress

This article was posted on 24 Sept 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

18 Sep 2014 | Armenia, Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan News, News, Turkey

On 5 September, Azerbaijaini president Ilham Aliyev addressed the Nato summit at the Celtic Manor golf resort in Newport, Wales.

It was an unspectacular speech from an unspectacular autocrat. As he often does, he talked about the amount of money Azerbaijan was spending abroad, Azerbaijan’s rapid economic development, Azerbaijan’s role as a bridge between east and west, and Azerbaijan’s continuing dispute with Armenia.

The dispute between the two countries over the territory of Nagorno-Karabakh, which has gone on pretty much since the break-up of the Soviet Union, flared as recently as this summer, when fourteen Azerbaijani troops were killed in clashes with their Armenian counterparts. It was easy to miss this, considering events in other parts of the former Soviet Union. As seems usual in international conflict now, neither side made any gain and both sides claimed victory.

A few weeks after that skirmish, and just before his Nato address, Aliyev met recently-elected president (formerly prime minister) Recep Tayyip Erdogan of Turkey. Aliyev is keen to build an alliance with Turkey, and clearly sees common cause in a shared dislike of Armenia. After the meeting, the Azerbaijani leader tweeted that “Turkey has always pursued an open policy on the issue of the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh, has always stood by Azerbaijan, stood by truth, justice and international law.” He went on:

This was interesting, in that Erdogan did not seem to mention any discussion of the Armenian genocide in his press briefing after the meeting. In fact, the Turkish president has been perceived as attempting to soften the Turkish state’s hardline denial of the incidents of 1915, when one million Armenians suffered deportation and death at the hands of the Ottoman Empire, the predecessor of modern Turkey.

In April, on the 99th anniversary of the beginning of the ethnic cleansing of Armenians, Erdogan released a statement saying: “Millions of people of all religions and ethnicities lost their lives in the first world war. Having experienced events which had inhumane consequences – such as relocation – during the first world war should not prevent Turks and Armenians from establishing compassion and mutually humane attitudes towards one another.”

The Justice and Development (AK) party leader went on to express condolences to the descendants of people who had died “in the context of the early 20th century”.

Now, this isn’t quite an apology; it’s barely even an apology at upset caused. It’s closer to the “mistakes were made” formulation, which is designed not so much to pass the buck as fire the buck into the heart of the sun in the hope that no one will ever have to deal with it again, particularly not the person whose buck it is in the first place.

But in the context of Turkey, where not long ago talking about the Armenian genocide could get you killed, it’s as good as you’re going to get for now.

So why would Aliyev raise the genocide issue this month? Perhaps he is nervous that Turkey, a major ally in the Nagorno-Karabakh dispute, is going soft on Armenia. This year’s detente between Turkey and Armenia continued when Armenia’s foreign minister Eduard Nalbandian attended Erdogan’s presidential inauguration at the end of August.

Nalbandian, in return, formally offered Erdogan an invitation to Armenia’s genocide commemorations next year, repeating an invitation first extended a few months ago by the country’s president Serzh Sargsyan. Any newfound good relations between Armenia and Turkey would severely weaken Azerbaijan’s territorial argument, or more accurately, weaken its ability to make the argument forcefully in the international arena. Turkey’s dispute with Armenia, after all, is mainly historic, and Erdogan, having seemingly consolidated his own power base outside of both the secular “deep state” and the Islamic Gülen movement to which many assumed he owed his success, now has a free hand on shaping foreign policy. Azerbaijan’s dispute with Armenia is current and, Aliyev hopes, immediate.

And so Azerbaijan has chosen to try to reignite the issue for its own ends. Meanwhile, in his own country, human rights abuses continue, with reports last week that Leyla Yunus, Director of the Institute for Peace and Democracy, was in ill health after prison beatings.

In spite of all this, Azerbaijan will continue to attempt to buy respectability. Next June, Baku will hold the first “European Games”, backed by the European Olympic Committee, featuring such irrelevancies as three-a-side basketball and beach soccer. It is not exactly the real thing, but then, post-Soviet Azerbaijan is a country built of facades; facades of modernity and wealth and progress and “democracy”. Facades that hide an underlying ugliness.

This article was posted on Thursday 18 Sept 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

17 Sep 2014 | Artistic Freedom, Index Arts, News, Religion and Culture, Turkey

Meltem Arikan is a Turkish playwright living in the United Kingdom.

“Oh, but of course,

you women have the right to speak!

Oh, but of course,

you have the right to laugh!

Oh, but of course,

you have a say over your bodies…

Oh, but of course,

freedom of expression!”

So they say, but in Turkey,

silence grows daily ever heavier

as the culture of fear expands.

If I shout ‘enough’,

will anyone hear my voice?

My voice…

a woman’s voice…

Aren’t women’s voices equivalent to muteness in Turkey?

As women begin to step outside the frames of their lives,

as modern tools for communication enlighten them about the world beyond,

the more curious they become

the more they inquire

the more they change

the more they demand more from their lives.

They dare to say no,

And they become those dangerous women

who are attempting to break the order…

Women, forced into passivity

scared to be counted as trouble makers,

they must be content to accept

the scraps thrown from men’s tables.

The traditional culture engenders fear

the fear of failure:

failing to satisfy the expanding demands of women

men lose self confidence,

when their constructed masculinity is perceived to be at risk,

they will stoop to violence and kill women and children.

So there are men

who feel that their manhood is under threat,

who take issue with their wives’ increasing demands,

who applaud this authoritarian system of government

as an example of how to deal with these problems.

Authority approves violence towards women,

the young and lesbian,

gay, bisexual and transgender people

by extending clemency to perpetrators of violence

instead of punishing them with the severity they deserve.

So there are men

Who are afraid facing up to their fear and pain.

Recoiling from pain and embarrassment of what has happened to them, rebound towards leaders

who apportion them so called high ideals.

So these men have become as dishonorable as the ones

who govern the country through fear and oppression.

Leaving aside, for the moment,

their antagonism towards organized resistance and protest,

just think: they can’t bear you,

the individual woman,

expressing your feelings

beyond the limitations they’ve decreed.

They can’t control their desire to destroy those

who raise their voices

who show resistance to their flawed dominance.

They’re always on the look-out for

the ‘other’,

an individual

or a group:

a race,

a sect

or a religion

on whom to project their hatred

and take revenge.

To mitigate their pain,

they target women,

the young:

anyone

or anything

that reminds them of their own inadequacies

and limitations.

Oppression first manifests in discourse…

Women are should have three children…

Women unveiled are like houses without curtains,

for rent or sale…

Women confirm that women who are raped

are at fault for wearing low cut dress.

It must be true: it’s reported in the press.

Women should not laugh in public.

Girls and boys must be educated separate.

No matter how much they want,

women can no longer shout out loud.

Enough is enough?

They cannot do it.

Shouting? Forget it!

Any female expression results in accusations,

exclusion and irreversible judgments.

If despite this

a woman insists on speaking her thoughts,

she will get a violent response

or at its extreme,

homicidal.

Perpetrate a greater violence

by politicking over women bodies

A genuine course of action against violence

would entail taking

their hands,

their politics

their ideas off women.

If I shout ‘enough’,

will anyone hear my voice?

My voice…

a woman’s voice…

Aren’t women’s voices equivalent to muteness in Turkey?

This poem was published on Wednesday Sept 17 at indexoncensorship.org