Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

Ugandan artists have for a long time been able to read the public mood in the country and have taken note of it in their plays and songs.

nder the military dictatorship of Idi Amin, a few brave artists expressed themselves through music and drama. Plays that were critical of the Amin regime were written and performed. Several of the authors were killed or forced into exile.

During the early years of President Yoweri Museveni’s National Resistance Movement (NRM) government, musicians, choreographers and playwrights promoted the new government through their works for bringing back stability after the overthrow of Obote and Lutwa regimes. The general public was full of praises for the new regime and artists tapped into that feeling.

However, as the early optimism waned, many artists became more critical. These artists have been censored, paid off or even deported, delivering big blows to artistic freedom of expression in Uganda in the process.

Nnabbi Omukazi composed a song in which she claimed to have had a dream where a dead politician told her that she did not die from cocaine, but that she had been poisoned.

.

It was believed to be about Cerinah Nebanda, a young, vocal and critical member of parliament who died early this year. The government quickly told the public it was from a cocaine overdose, but her family and some members of parliament were not convinced by this explanation. They decided to hire a pathologist to take body samples of the deceased to South Africa to ascertain the cause of death. The pathologist was intercepted by security en-route to the airport and detained, which compounded the family’s suspicion that the MP had been poisoned because of her critical stance on several government positions. For composing that song, Police interrogated Nnabbi, and her song was banned from the airwaves.

Another artist, Matthias Walukagga, composed the song Tuli bakoowu (We are tired) in which he indirectly hints at the president’s overstay in power. In one verse, the artist asks; “When will the old man also declare that he is tired.” This song was banned on airwaves, but people still buy the CD’s and play it.

One of the biggest Ugandan artists, Bobi Wine aka “Ghetto President” wrote a song criticizing the way small traders in Kampala were being mistreated by the city authorities. In his song Tugambire ku Jennifer (Tell Jennifer to stop harassing us) Bobi attacks Jennifer Musisi, the Executive Director of Kampala Capital City Authority, for not caring about the plight of the poor and only protecting the interests of the rich. Responding to Bobi’s song, Musisi first dismissed it as one without consequence. However, when she realised the pressure the song was creating from the poor city dwellers, she invited Bobi to ceasefire talks. He also walked away with a fat contract to promote city activities starting with the Kampala Carnival 2013, taking place on 6 October 2013.

Patronage does not stop with politicians, it extends to almost all spheres of Ugandan society. Several other performing artists have been given fat contracts from State House (the President’s residence) to work for the presidency in different areas. In fact today, one will see a bus full of artists going to State House on invitation from the President to discuss “issues of national importance.”

Richard Kaweesa and Isaac Rucibigango, both smart and intelligent performing artists composed the song “You want another Rap”, which President Museveni used to woo young voters in the 2011 elections. This song went viral on social media and it worked in the president’s favor. The two artists were handsomely paid by the presidency. Again in 2012 when Uganda was marking 50 years of independence, Kaweesa was given another deal from State House to compose the Jubilee song. This earned him a reported 600 million shillings (US Dollars 235,300).

The same trend can be seen with comedians, as several have specialised in imitating big politicians. Segujja Museveni has perfected the art of mimicking President Museveni and has on several occasions been invited to perform for him. At his first performance before the president, he laughed so hard he had to wipe away tears. It was the first time the nation saw the president have such a hearty laugh. Since then, Segujja’s career has been on a meteoric rise.

As for dramatic artists; they are still reluctant to freely express themselves because of the potential consequences. However, they keep on making references to the political, economical and social spheres of Uganda in their plays. One artist that did this was British-born theatre producer David Cecil. He was deported from Uganda in February 2013 after being accused of staging a play promoting homosexuality. This was at a time when the government of Uganda was up in arms against anyone who seemed not to have a problem with homosexuality.

Most artists have decided to play it safe by keeping away from controversial issues, mainly political, that affect society. Sarah Zawedde, a musician says that the biggest threats to artistic freedom in Uganda are from the cultural, religious and political spheres.

(Photo illustration: Shutterstock)

In May this year, the Ugandan government closed two newspapers. The crime The Monitor and The Red Pepper newspapers committed was publishing a letter by the now renegade former Coordinator of Security Services, General David Sejusa, in which he claimed that President Yoweri Museveni was grooming his son Muhoozi Kainerugaba to succeed him. In the same letter, General Sejusa claimed that there was a plot to assassinate all army officers and senior government officials who are against the president’s succession plan.

The letter had been written to the Internal Security Organization (ISO) boss to investigate the allegations, but was leaked to the media. Despite this, the government went ahead and closed the two media houses which had run the story for two weeks. They were only allowed to reopen after meetings with the minister of internal affairs, where the editors were told that government would not hesitate to close the media houses for good if they did not stop “reporting irresponsibly.” These are the only privately owned dailies in the country.

This was not The Monitor’s first run-in with the government. At its inception in the early 1990’s, it was the only privately owned daily that competed with the government-owned New Vision. New Vision towed the government line as a mouthpiece and enjoyed all the advertising deals from all government ministries and agencies. The Monitor was totally denied all government adverts, with the intention of killing it off because it was the only paper that was questioning government decisions on different issues. It was the readership plus some support from private businesses that kept it alive. The African Centre for Media Excellence (ACME) has also criticised the paper and its sister FM station, KFM, for bending under government pressure. This came after it pulled down a critical story about the president, claiming that it had been badly written.

Print media is not alone in being targeted. During the 2009 riots that rocked Uganda, the government closed five privately owned FM radio stations reporting on it. Four of them were reopened after six weeks, after they had publicly apologised to the president and promised never to do that again. Central Broadcasting Services (CBS), however, was closed for over a year. It took a lot of pleading to the president from the media, church, monarchy and other wealthy and influential people to reopen CBS. Since it went back on air, most of the political discussions were bumped off air and some individuals who government felt were anti-establishment were barred from appearing as panelists on the different radio talk shows.

To add to the problem, the government also directly controls a wide range of media. New Vision is run under the government-owned Vision Group and is building up a powerful media conglomerate with four other newspapers publishing in local languages, three television stations, three radio stations in the capital Kampala, plus other local radio stations in at least all the other regions of the country. All these are strictly government mouthpieces, and management will not allow opposition politicians or activists to use these platforms to reach the masses. The national broadcaster, Uganda Broadcasting Corporation (UBC), which runs the national television station and a multitude of radio stations in the countryside, is also tightly under government control.

Furthermore, while Uganda is seen in the East African region as having the best and less repressive media legislation, the government has of late tended to make amendments to the existing media laws to make them restrictive. The African Media Barometer (AMB), which is made up of leading media practitioners in the country from private and government-owned media houses, as well as lawyers and representatives from civil society, reported in 2012 that there are a few positive developments in Uganda with the licensing of more print and electronic media outlets. However, AMB also notes that the media freedom declines ahead of elections as the government grows increasingly nervous and attempts to clamp down on freed speech. Private media houses, especially radio stations, also practice self-censorship in order not to annoy the powers that be.

Ibrahim Bisika from the government’s Media Centre says the friction between media and government arises out of “editorial mismanagement” where media houses publish stories that bring them in direct confrontation with government. Moses Serwanga, a director at the Uganda Media Development Foundation (UMDF) says that media freedoms in the country are getting curtailed because of the creeping political dictatorship where political leaders do not want to leave office.

The heroine of The Little Maid, Viola, is an eight-year-old Ugandan girl who lives with her destitute grandmother and dreams of going to school. Instead, she is sent to live with her aunt, who promises to pay her school fees if Viola works for her first. Viola becomes a maid, forced to wash clothes, scrub the bathroom, cook and live in servants’ quarters. But every day when her cousins’ tutor arrives, she crawls underneath the dining room table to eavesdrop on the lessons. Eventually Viola learns to read and write and escapes the clutches of her evil aunt, who is found guilty of child abuse and child slavery and ordered to school her niece.

The heroine of The Little Maid, Viola, is an eight-year-old Ugandan girl who lives with her destitute grandmother and dreams of going to school. Instead, she is sent to live with her aunt, who promises to pay her school fees if Viola works for her first. Viola becomes a maid, forced to wash clothes, scrub the bathroom, cook and live in servants’ quarters. But every day when her cousins’ tutor arrives, she crawls underneath the dining room table to eavesdrop on the lessons. Eventually Viola learns to read and write and escapes the clutches of her evil aunt, who is found guilty of child abuse and child slavery and ordered to school her niece.

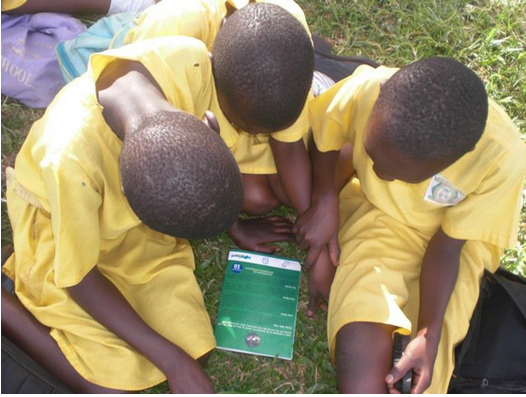

It could be a true story. In Uganda there are an estimated 2.75 million children engaged in work, although not many of those will have the happy ending. But The Little Maid is a work of fiction, written by Oscar Ranzo, a Ugandan social worker turned author who has penned five children’s books. Now, The Little Maid is being distributed to schools across the country low-cost (5,000 Ugandan shillings or $1.90 each) through his Oasis Book Project. The project aims to improve the reading and writing culture in Uganda and provide school-children with entertaining but educational stories to which they can relate. Ranzo sells most of his books to schools, with the proceeds used to publish more titles. However, he also donates copies to more impoverished areas.

In 1969, Professor Taban Lo Liyong, one of Africa’s best-known poets and fiction writers, declared Uganda a ‘literary desert’. “What we want to do with this project is create an oasis in the desert,” explains Ranzo. “That’s why I called it the Oasis Book Project.”

Excluding textbooks, there are only about 20 books published in Uganda annually. According to a study last year by Uwezo, an initiative aimed at improving competencies in literacy and numeracy among children aged six to sixteen years in East Africa, more than two out of every three pupils who had finished two years of primary school failed to pass basic tests in English, Swahili or numeracy. For children in the lower school years, Uganda recorded the worst results.

Growing up in the 1970s and 1980s, Ranzo was privileged to have a grandfather who had a library and attended a private school that held an after class reading session. He was a particularly avid fan of Enid Blyton’s Famous Five series.

“But Mum was a nurse and she wanted me to be a doctor. I wanted to pursue literature and she told me ‘no you can’t do that’, so I did sciences,” says Ranzo, stressing that literature, which remains optional in secondary school, is not taken seriously in Uganda.

Furthermore, many local publishers do not see writing fiction as profitable. “They’d rather publish textbooks and get the government to buy them,” Ranzo explains.

His books are available in two central Kampala bookshops for 8,000 shillings ($3). But in the past 15 months fewer than 20 have moved from the shelves, while he has sold over 3,000 to 20 schools in three districts.

Saving Little Viola, his first book in which the female protagonist, Viola, was introduced, was published in 2011 by NGO Lively Minds. The story ends with Viola being saved by her best friend from two men who want to use her for a ritual sacrifice. UNICEF funded its distribution to 36 primary schools across Uganda as part of a child sacrifice awareness programme.

The primary aim of the Oasis Book Project is to encourage reading, although Ranzo admits he would like people to discuss his stories, which have themes close to his heart. Children being forced into work, the theme of The Little Maid, is something he has witnessed himself.

“Many kids are brought from villages to work as maids in homes in towns or cities, and the treatment they are subjected to is terrible in many cases,” says Ranzo.

His next book, The White Herdsman, which will be released in 2014, deals with the impact of oil production on communities, a timely subject for Ugandans with oil production expected to start in 2016. The book tells the story of a village where water in the well has turned black after an oil spill. A witchdoctor blames the disaster on an albino child.

Ranzo’s stories have been welcomed at Hormisdallen Primary, a private school in Kamwokya, Kampala. English teacher Agnes Kasibante, speaking to Think Africa Press, praises the book’s impact. “It’s actually a big problem in Uganda, most children don’t know how to read. At least those books give them morale to continue loving reading,” she says.

Ranzo has also penned Cross Pollination, a collection of fictional stories for adults about the spread of HIV in a community. According to a recent report, Uganda may not meet its target to increase adult literacy by 50% by 2015.

“I’ve worked in a big multinational company where people have jobs but they can’t write. Reading can help develop this,” says Ranzo, who is currently attending the University of Iowa’s 47th annual International Writing Program (IWP) Fall Residency.

Jennifer Makumbi, 46, a Ugandan doctoral student at Lancaster University, is one of a new generation of Ugandan authors. She won the Kwani Manuscript Project, a new literary prize for unpublished fiction by Africans, for her novel The Kintu Saga. She said Taban Lo Liyong’s description of Uganda as a literary desert was “heartbreaking, especially as in the 1960s Uganda seemed to be poised to be a leading literary producer”.

“But perhaps it is exactly this description that is pushing Ugandans to write in the last ten years,” she continues. “Yes, we have not caught up with West Africa yet but… there are quite a few wins.” In recent years, two female Ugandan authors, Monica Arac de Nyeko and Doreen Baingana, won the Caine Prize for African Writing and the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize respectively. Makumbi’s Kwani prize adds her to a list of eminent Ugandan authors.

Makumbi is optimistic about the future of Ugandan literature: “These I believe are indications that Uganda is on its way.”

Index on Censorship has joined Human Rights Network for Journalists-Uganda (HRNJ-Uganda) in writing a letter of protest to the country’s president President Yoweri Museveni, after the network’s national coordinator, Geoffrey Wokulira Ssebaggala was attacked and arrested by police, Padraig Reidy reports.