12 Jan 2022 | News and features, Russia, Ukraine

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”118142″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]On 10 January 2022, Yuri Dmitriev, a historian prosecuted on disputed charges of paedophilia, and his lawyers lodged appeals with the Supreme Court of Karelia where he was prosecuted. Dmitriev’s case is part of a long-running battle between the authorities and the Memorial Human Rights Centre (MHRC), whose Karelia branch was led by the historian.

The battle may be drawing to a conclusion. Two weeks’ earlier, on 28 December 2021, Russia’s Supreme Court ordered the dissolution of MHRC, which was established in 1988 by young reformers and Soviet dissidents. It was accused of not using the “foreign agent” designation on all its material indicating that it was a body “receiving overseas funding and engaging in political activities”. Prosecutor Zhafyarov also denounced Memorial for painting “the USSR as a terrorist state”.

The decision indicates that Russian President Vladimir Putin is now blatantly rehabilitating the USSR. Dmitriev’s prosecution in 2016 dates from an era when the regime was more veiled in its attack on critics of the regime. Another historian Sergei Koltyrin, who also researched Stalinist crimes in Karelia, was arrested on disputed paedophilia charges in 2018. He died in a prison hospital on 2 April 2020; Dmitriev and his defence attorney fought several appeals but on 27 December 2021 he was sentenced to 15 years in a strict-regime penal colony.

“Their real crime,” says John Crowfoot of the Dmitriev Affair website, “was to commemorate the victims of Stalinism, in particular the thousands shot at Sandarmokh killing field during the Great Terror (1937-1938).” Sandarmokh is the last resting place for as many as 200 members of Ukraine’s Executed Renaissance, who were leading figures in the blossoming of Ukrainian culture during the 1920s.

The imminent closure of Memorial will sicken many in Ukraine, where an estimated 3.9 million people died in the Holodomor famine genocide, a topic which the organisation has also helped research. Similar concern will be felt in the Baltic States and Kazakhstan, where up to 1.5 million people died of a famine related to collectivisation in 1931-33 and where Russian troops have been involved in violently crushing protests since the beginning of January 2022.

Even before the dissolution of Memorial there were attempts to restrict the discussion around Soviet-era crimes in Russia. In 2011, for example, historians were instructed to compile archival documents to deny the unique character of famine in Ukraine during 1932-33 and instructed on how to write about the subject. Yet numerous documents indicate that Ukraine and ethnically Ukrainian areas of Russia were targeted (in particular the 23 January 1933 directive sealing the borders of these areas to stop peasants fleeing starvation). And in 2008 a letter from Russian president Dmitry Medvedev to Ukrainian president Viktor Yushchenko continued the line that it was simply a tragedy when he wrote that “the tragic events of the 1930s are being used in Ukraine in order to achieve instantaneous and conformist political goals.”

There are already laws outlawing comparisons of the Soviet Union to Nazi Germany as of June 2021. But how will the decision affect debate in Russia now? According to Memorial, who I contacted for this article, their dissolution means that now, “there is only one point of view that is acceptable in discussions on historical topics, that of the state”.

Putin is playing up nostalgia for the Soviet Union. He is even surrounding Ukraine with troops and possibly considering an invasion in an attempt to boost his flagging popularity. The closure of Memorial combined with troop movements is one of many signals that he is considering not only rehabilitating but even perhaps partly renewing the Soviet Union by annexing Ukraine.

However, rather than enthusiastically flocking to join the new union Ukrainians are enlisting in territorial defense units.

Thanks in part to the work of Memorial, and Russian and Ukrainian demographers and archivists, they know that millions of their family members died at the hands of the regime and they do not want to relive that experience. Putin may succeed in stifling debate in the media and in universities but he cannot stop people in a country as big as Russia from talking. The mass graves in the tundra and across many former Soviet countries cannot be censored off the map.

Steve Komarnyckyj an award-winning poet and translator. He works on Ukrainian literary translations and is currently producing a book by Lina Kostenko[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row]

10 Dec 2020 | Opinion, Ruth's blog

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”115786″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]Today we once again marked Human Rights Day. A day that gives us an opportunity to reflect on how far we’ve come as a society of nations and yet how far we still have to go before the aspiration of protected human rights is universally applied.

On the 10th December 1948, 72 years ago, the UN General Assembly adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. In theory, the UDHR gives everyone of us, wherever we live, an expectation of minimum rights. It outlines a framework of what we as citizens can and should expect from our political leaders. And it sets the rules for nation states about what is and is not acceptable.

As Eleanor Roosevelt stated when she addressed the UN Assembly on that fateful day:

“We stand today at the threshold of a great event both in the life of the United Nations and in the life of mankind, that is the approval by the General Assembly of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights recommended by the Third Committee. This declaration may well become the international Magna Carta of all men everywhere. We hope its proclamation by the General Assembly will be an event comparable to the proclamation of the Declaration of the Rights of Man by the French people in 1789, the adoption of the Bill of Rights by the people of the United States, and the adoption of comparable declarations at different times in other countries.”

Index lives and breathes the UDHR. Our fight against censorship is based on Article 19 of the Declaration. We exist to promote and defend the basic human rights that were espoused that day.

Unfortunately, we remain busy.

There are still too many daily examples of egregious breaches of our basic human rights throughout the world. Index was established to provide hope to those people who lived in repressive regimes, so that they knew their stories were being told, not to be a grievance sheet but rather a vehicle of hope. But too many repressive governments are ignoring their obligations and persecuting their citizens. And too many democratic governments seemingly believe that the spirit of the UDHR (never mind their own legal frameworks) don’t necessarily apply to them.

This year alone we have learnt of the appalling Uighur camps in Xinjiang province, China; we’ve seen the Rohingya denied the right to vote in Myanmar; we’ve watched in horror as Alexander Lukashenko attempted to fix his re-election and then tried to crush the opposition in Belarus. We’ve seen journalists arrested in the USA for covering the Black Lives Matter protests; human rights activists imprisoned in Egypt and dancers arrested in Iran for daring to dance with men.

When you see the scale of the battles ahead in the fight to defend our human rights it is easy to feel overwhelmed. But there are things that each one of us can do to make a difference. As we approach the end of 2020 we’re asking you to send a message of hope to six people who are currently imprisoned for exerting their rights to free speech. Included in our #JailedNotForgotten campaign are the following brave individuals:

- Aasif Sultan, who was arrested in Kashmir after writing about the death of Buhran Wani and has been under illegal detention without charge for more than 800 days;

- Golrokh Emrahimi Iraee, jailed for writing about the practice of stoning in Iran;

- Hatice Duman, the former editor of the banned socialist newspaper Atılım, who has been in jail in Turkey since 2002;

- Khaled Drareni, jailed in Algeria for ‘incitement to unarmed gathering’ simply for covering the weekly Hirak protests that are calling for political reform in the country;

- Loujain al-Hathloul, a women’s rights activist known for her attempts to raise awareness of the ban on women driving in Saudi Arabia;

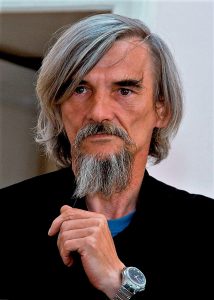

- Yuri Dmitriev, a historian being silenced by Putin in Russia for creating a memorial to the victims of Stalinist terror and facing fabricated sexual assault charges.

We may not be able to send a message to every person currently being persecuted for exercising their right to free expression, but we can send a message of hope to Aasif, Golrokh, Hatice, Khaled, Loujain and Yuri. We will use our voices as much as possible to try and ensure they are not still in prison for the 2021 World Human Rights Day.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row]

19 Oct 2020 | News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

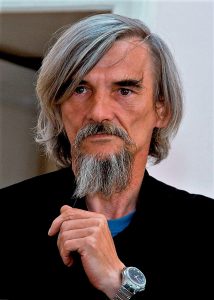

Russian historian Yuri Dmitriev, who has been imprisoned following research into murders committed by Stalin. Credit: Mediafond/Wikimedia

Western democracies have expressed concern and outrage, at least verbally, over the Novichok poisoning of Alexei Navalny—and this is clearly right and necessary. But much less attention is being paid to the case of Yuri Dmitriev, a tenacious researcher and activist who campaigned to create a memorial to the victims of Stalinist terror in Karelia, a province in Russia’s far northwest, bordering Finland. He has just been condemned on appeal by the Supreme Court of Karelia to thirteen years in a prison camp with a harsh regime.

The hearing was held in camera, with neither him nor his lawyer present. For this man of sixty-four, this is practically equivalent to a death sentence, the judicially sanctioned equivalent of a drop of nerve agent.

After an initial charge of child pornography was dismissed, Yuri Dmitriev was convicted of sexually assaulting his adoptive daughter. These defamatory charges appear to be the latest fabrication of a legal system in thrall to the FSB—a contemporary equivalent, here, of the nonsensical slander of “Hitlerian Trotskyism” that drove the Great Terror trials. It is these same charges, probably freighted with a notion of Western moral decadence in the twisted imagination of Russian police officers, that were brought in 2015 against the former director of the Alliance Française in Irkutsk, Yoann Barbereau.

I met Yuri Dmitriev twice: the first time in May 2012, when I was planning the shooting of a documentary on the library of the Solovki Islands labor camp, the first gulag of the Soviet system; and the second in December 2013, when I was researching my book Le Météorologue (Stalin’s Meteorologist, 2017), on the life, deportation, and death of one of the innumerable victims murdered by Stalin’s secret police organizations, OGPU and NKVD.

In both cases, Dmitriev’s help was invaluable to me. He was not a typical historian. At the time of our first meeting, he was living amid rusting gantries, bent pipes, and machine carcasses, in a shack in the middle of a disused industrial zone on the outskirts of Petrozavodsk—sadly, a very Russian landscape. Emaciated and bearded, with a gray ponytail, he appeared a cross between a Holy Fool and a veteran pirate—again, very Russian. He told me how he had found his vocation as a researcher—a word that can be understood in several senses: in archives, but also on the ground, in the cemetery-forests of Karelia.

In 1989, he told me, a mechanical digger had unearthed some bones by chance. Since no one, no authority, was prepared to take on the task of burying with dignity those remains, which he recognized as being of the victims of what is known there as “the repression” (repressia), he undertook to do so himself. Dmitriev’s father had then revealed to him that his own father, Yuri’s grandfather, had been shot in 1938.

“Then,” Dmitriev told me, “I wanted to find out about the fate of those people.” After several years’ digging in the FSB archive, he published The Karelian Lists of Remembrance in 2002, which, at the time, contained notes on 15,000 victims of the Terror.

“I was not allowed to photocopy. I brought a dictaphone to record the names and then I wrote them out at home,” he said. “For four or five years, I went to bed with one word in my head: rastrelian—shot. Then, I and two fellow researchers from the Memorial association, Irina Flighe and Veniamin Ioffe (and my dog Witch), discovered the Sandarmokh mass burial ground: hundreds of graves in the forest near Medvejegorsk, more than 7,000 so-called enemies of the people killed there with a bullet through the base of the skull at the end of the 1930s.”

Among them, in fact, was my meteorologist. On a rock at the entrance to this woodland burial ground is this simple Cyrillic inscription: ЛЮДИ, НЕ УБИВАЙТЕ ДРУГ ДРУГА (People, do not kill one another). No call for revenge, or for putting history on trial; only an appeal to a higher law.

Memorials to the victims of Stalin’s Terror at Krasny Bor, Karelia, 2018; the remains of more than a thousand people shot between 1937 and 1938 at this NKVD killing field were identified by Dmitriev, using KGB archival records

Not content to persecute and dishonor the man who discovered Sandarmokh, the Russian authorities are now trying to repeat the same lie the Soviet authorities told about Katyn, the forest in Poland where NKVD troops executed some 22,000 Poles, virtually the country’s entire officer corps and intelligentsia—an atrocity that for decades they blamed on the Nazis. Stalin’s heirs today claim that the dead lying there in Karelia were not victims of the Terror but Soviet prisoners of war executed during the Finnish occupation of the region at the beginning of World War II. Historical revisionism, under Putin, knows no bounds.

I am neither a historian nor a specialist on Russia; what I write comes from the conviction that this country, for which I have a fondness, in spite of all, can only be free if it confronts its past—and to do this, it needs courageous mavericks like Yuri Dmitriev. And I write from the more personal conviction that he is a brave and upright man, one whom Western governments should be proud to support.

This article was translated from the French by Ros Schwartz. It was originally published on the New York Review of the Books here under the headline Yuri Dmitriev: Historian of Stalin’s Gulag, Victim of Putin’s Repression.

Read our article exploring Dmitriev’s case and how history is being manipulated and erased here.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]