Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

Richard Dawkins and ex-Muslim campaigner Maryam Namazie at a rally in support of free expression, London, February 2012. Image Demotix/Peter Marshall

This week has seen an outbreak of atheist infighting, as Observer and Spectator writer Nick Cohen launched an attack at writers such as the Independent’s Owen Jones and the Telegraph’s Tom Chivers. Their crime, apparently was to focus criticism on atheist superstar Richard Dawkins for his tweets, particularly those about Islam and Muslims, while not criticising religious fundamentalists.

Jones and Chivers have both replied, quite reasonably, to Cohen’s article.

Dawkins’s controversial tweets display a political naivety that can often be found in organised atheism and scepticism. Anyone who’s witnessed the ongoing row within that community over feminism will recognise a certain tendency to believe that science and facts alone are virtuous, and “ideologies” based on something other than empirical data just get in the way.

Hence the professor can tweet the statement “All the world’s Muslims have fewer Nobel Prizes than Trinity College, Cambridge” as if this in itself proves something, without further thinking about the political, historical, social and, indeed, geographical factors behind this apparent fact, and then be surprised when people object.

I’m not going to suggest that Dawkins be silenced. He can and will tweet what he wants. And it’s worth pointing out that those on the liberal left who have raised concerns about Dawkins’s pigeonholing of Muslims can be equally guilty of treating all adherents to a religion as a monolithic bloc: this happens mostly with Muslims, but often, at least in the UK with Roman Catholics as well, as if declaring the shahada or accepting the sacraments is akin to being assimilated into Star Trek’s Borg. Any amount of non-Muslim commentators who opposed the Iraq war, for example will tell you that “Muslims” care deeply about the Iraq war, neatly soliciting support for their arguments while also casting themselves as friends of a minority group. And for a great example of treating “Catholics” as a single entity, Johann Hari’s address ahead of the visit by former pope Benedict XVI to Britain in 2010, takes some beating:

I want to appeal to Britain’s Roman Catholics now, in the final days before Joseph Ratzinger’s state visit begins. I know that you are overwhelmingly decent people. You are opposed to covering up the rape of children. You are opposed to telling Africans that condoms “increase the problem” of HIV/Aids. You are opposed to labelling gay people “evil”. The vast majority of you, if you witnessed any of these acts, would be disgusted, and speak out. Yet over the next fortnight, many of you will nonetheless turn out to cheer for a Pope who has unrepentantly done all these things.

I believe you are much better people than this man. It is my conviction that if you impartially review the evidence of the suffering he has inflicted on your fellow Catholics, you will stand in solidarity with them – and join the [anti-Pope] protesters.”

Hari is literally telling people what they think. A bit like the Vatican tries to do.

Communalist rhetoric, whether used to attack or support certain groups, is the enemy of free speech, as it automatically discredits dissenting voices: “If you do not believe X, as I say members of group Y do, then you cannot be a true member of the group; ergo you can be ignored, or censored.”

Nowhere is this more evident than in India, where communalism, thanks to the British Empire, is enshrined in law. The 1860 penal code of India makes it illegal to “outrage religious feelings or any class by insulting its religion or religious beliefs”. This establishes, in an odd inversion of the United States’s model of secularism, a state where all religions are privileged, while those who criticise them are unprotected. And in India, that can be dangerous.

Sixty-seven-year-old Narendra Dabholkar was killed this week, shot dead on his morning walk.

Dabholkar was a rationalist activist, in a country where that means a little bit more than agreeing or disagreeing with Richard Dawkins. Dabholkar and his comrades such as Sanal Edamaruku have for years been engaged in a war against the superstition that leaves poor Indians open to exploitation from “holy men”. A large part of their work involves revealing the workings of the tricks of the magic men, like a deadly serious Penn and Teller. Edamaruku famously appeared on television in 2008, trying not to laugh as a guru attempted to prove that he can kill the rationalist with his mind. Dabholkar was agitating for a bill in that would curtail “magic” practitioners in Maharashtra state.

Edamaraku is now in exile, fleeing blasphemy charges and death threats that resulted after he debunked the “miracle” of a weeping statue at a Mumbai Catholic church. His friend is dead. Both victims of those who have most to gain from communalism: the con men and fundamentalists for whom the individual dissenting voice is a threat. Atheists, sceptics and everyone else have a duty to protect these people, and to avoid easy generalisations, whether malicious or well meant.

(Photo illustration: Shutterstock)

Though it has a reasonably good freedom of expression environment, the United Kingdom is wrestling with the fallout from mass surveillance leaks, press regulation, web filtering and social media guidelines. With an unwritten constitution, the right to freedom of expression comes from the practice of the common law, alongside the UK’s accession to international human rights instruments.

There have been positive developments in the UK on free speech in the last year with reform to defamation law and reform of section 5 of the Public Order Act.

The law of libel has been reformed by the Defamation Act which received Royal Assent on 25 May 2013. The reformed law, when enacted will restrict “libel tourism”, bring in a hurdle to prevent vexatious claims, update the provisions on internet publication, force corporations to prove financial loss and introduce a reasonable public interest defence. This reform will strengthen freedom of expression protections for academics, journalists and bloggers, scientists and NGOs.

Free speech is also enhanced by the United Kingdom’s strong Freedom of Information laws. Information requests are on the whole free with over 90% of requests receiving a response on time.

The recent Justice and Security Act can be used to exclude the media from hearings to consider whether a secret evidence procedure is to be used. This may cover cases where claimants have been subject to extra-judicial detention, torture and extraordinary rendition, affecting the media’s ability to perform its watchdog function.

The UK has tough state secrecy legislation. The public interest defence in the Official Secrets Act was removed in 1989 and has not been replaced.

While the freedom to protest is well-established, the use of “kettling” to deter protestors and the prosecution of “offensive” protest including the burning of military symbols and homophobic street preaching is of concern. Scotland’s recent anti-sectarian laws have criminalised “offensive” speech at football matches.

Media freedom

The publication of mass surveillance revelations by The Guardian’s Glenn Greenwald has had reverberations around the world. The UK government has moved toward confrontation with the news organisation by forcing the destruction of hard drives that contained documents leaked by former NSA contractor Edward Snowden. The recent developments around the detention of David Miranda and the seizure of material he was carrying under Section 7 of the Terrorism Act has raised concerns over press freedom.

The UK fares well internationally for media plurality with 23 independent national newspapers, as well as several hundred regional and local papers. The main TV stations are all available with every station provider. While Index believes there is strong media plurality in the UK at present, the legal framework may not be sufficient to ensure plurality in the future, as demonstrated by News Corporation’s attempted takeover of BskyB.

The phone hacking scandal exposed criminality in the British media, yet the response to the scandal has imperilled media freedom. The creation of a Royal Charter drawn up by the three main political parties to create a media regulator warranted the first government interference into the process of press regulation since 1695. Considerable confusion remains since no newspaper has agreed to be part of the new regulator. This leaves the possibility of independent regulation in the near-future.

Digital freedom

The UK upholds online freedom in comparison with other comparable democracies, but there are worrying trends on the criminalisation of social media, mass surveillance and proposals to introduce web filters.

The Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000 increased the powers of the police to intercept communications. In 2012, the government attempted to extend this surveillance with its draft Communications Data Bill. The Bill would have made the surveillance and storage of UK citizens’ communications data the norm allowing an intrusion into the privacy of British citizens that would have chilled free expression. The Bill was dropped after a parliamentary committee criticised the scope of the legislation, but the Home Secretary has indicated she would like to bring forward a similar law.

Revelations of cooperative relationships between the United State’s National Security Agency and the UK’s Government Communications Headquarters as part of the mass surveillance programmes has raised serious concerns around digital freedom of expression. At the same time it is surveilling citizens’s online communications, the country is in the initial stages of possibly instituting opt-out web filters to block pornography with a consultation set to begin on 27 Aug.

The framework for copyright also has the ability to impede freedom of expression. The Digital Economy Act contains provisions allowing the government to order internet service providers (ISPs) to block websites and suspend accounts for customers accused of downloading copyrighted material.

The UK has high levels of take-up of social media and internet access. However, access is still not universal with exclusion from the internet for marginalised individuals a barrier to free speech. The recently launched Web Index report shows that the UK leads in the use of online citizen e-petitioning.

The police and executive bodies make a significant number of takedown requests to remove content according to Google’s transparency reports.

There have been an increasing number of arrests and prosecutions for ‘offensive’ comments on social media after public complaints. The Crown Prosecution Service has produced guidelines to limit the number of arrests and prosecutions. The legal framework has also been reformed with Section 5 of the Public Order Act no longer criminalising insulting behaviour or content. However, restrictive laws still apply with Section 127 of the Communications Act criminalising “grossly offensive” comments.

Artistic freedom

The UK continues to produce challenging art in a free environment for artistic freedom of expression but a chill remains around social, religious and cultural pressures on the arts and inconsistent policing of art deemed to be offensive.

A lack of guidance on the policing of culture has on occasion created significant problems for artistic freedom of expression. Large demonstrations outside performances of Gurpreet Kaur Bhatti’s play Behzti led to the play being closed down after guidance from the police. Her play about this situation, Behud – Beyond Belief was treated as a potential threat to public order with the police in Coventry asking for a fee of £10,000 per night. Policing can also be arbitrary. In 2012, a police officer told a Mayfair art gallery to remove a photo-montaged image of ancient myth Leda and the Swan from its window, despite the fact no one had complained.

While direct censorship of the Arts remains uncommon, self-censorship by artists is more routine. Artists self-censor for a number of reasons including fear of causing controversy or offence combined with special interest group campaigns that put pressure on artists to censor, financial pressures with artistic institutions not wanting to court controversy, cultural diversity policies that may encourage self-censorship and a habit of risk aversion that leads cultural institutions to focus on worst case scenarios of what might happen when taking artistic risks.

This article was originally published on 23 Aug, 2013 at indexoncensorship.org.

After a long day of work and parenting, my wife and I read our child stories in the hope that her five-year old brain and body will drift into slumber before ours do. This time spent together reading is a special, private respite from the demands of the day. We bond and have fun and our daughter learns about the world through the books we choose to read.

After a long day of work and parenting, my wife and I read our child stories in the hope that her five-year old brain and body will drift into slumber before ours do. This time spent together reading is a special, private respite from the demands of the day. We bond and have fun and our daughter learns about the world through the books we choose to read.

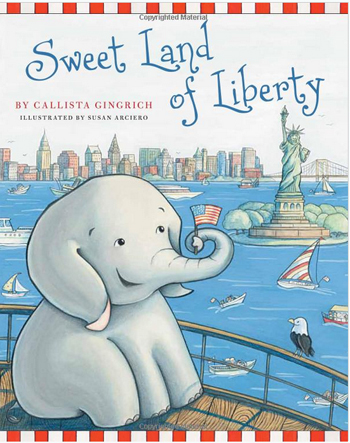

The magic of this bedtime ritual was recently threatened when a well-meaning relative invited Callista Gingrich to join us by giving our daughter her book, Sweet Land of Liberty, as a birthday gift. As parents on the other end of the political spectrum, the sight of the happy Republican elephant on the cover waving an American flag with its trunk while staring at the Statue of Liberty (next to a seagull that looks curiously like a shrunken bald eagle) evoked cringes and irritation.

My wife and I noted that “shelving” the book could teach our child that generous gifts can be easily discarded and that it is acceptable to allow them to go unappreciated. We decided that we would read the book at bedtime and that we would, no matter how tempting, not ridicule the book. I faithfully carried out the reading phase of the decision but was unable to resist ridicule.

America is a special country with amazing wealth and an impressive capacity for innovation and industry. That being said, the first paragraph on the first page states that the elephant was “eager to see how America became the land of the free.” I know my nation’s national anthem contains those lyrics but our child must know that America is not the only land whose citizens are free. We discussed how people in many other countries are similarly free to do as they please.

The next page addresses the arrival of the pilgrims to North America. It states of the pilgrims, “with the help of God, they survived cold and beast and celebrated together with a Thanksgiving feast.” The illustration shows Native Americans and pilgrims at a table together with the Native Americans looking to the pilgrims with approving and admiring smiles. We talked about how, in addition to any help from God, the Native Americans taught the pilgrims skills for surviving in the new world and that, without those skills, the pilgrims were suffering badly. They deserved the pilgrims’ thanks too.

It was on the page addressing Abraham Lincoln that I was most bemused. Calista writes “throughout the Civil War, President Lincoln stood tall. His leadership was admired by one and by all.” At that point in the book and the day, I could only muster the crack that, while I am no historian, I am quite confident that there was at least one man that did not admire Linclon’s leadership or, if he did, he had a very strange way of showing his admiration.

In all fairness, Olive did say that the elephant is cute.

Bryan Biedscheid is an attorney in Santa Fe, New Mexico

Index on censorship has called upon the G20 countries to put free speech on the agenda when they meet in Saint Petersburg, Russia for a summit on 5-6 September.

Index on Censorship Campaigns and Policy Director Marek Marczynski said:

“The G20 should not solely be about advancing economic development but also about advancing the human rights of citizens within the G20 and beyond. Following recent revelations about mass surveillance by the US, the UK and other countries, it is more important than ever that they clearly express their commitment to freedom of speech, the freedom of the media and individuals’ rights to privacy. The G20 should be on the forefront of protecting those rights and freedoms in their own countries and globally.”

Files leaked by whistleblower Edward Snowden have revealed the extent of surveillance by the NSA in the US and GCHQ in the UK. It is time for the G20 leaders to be transparent about the activities they carry out in the name of national security and consider the impact that they have on their citizens. Any measures to restrict freedom of speech, privacy and other human rights in the name of the fight against terrorism should be within the permissible legal limits. They can only be justified if they are necessary in a democratic society.

In the lead up to the summit, Index has been publishing articles exploring the free expression records of some of the G20 nations. The ongoing series can be found here.