12 Sep 2013 | Guest Post, News and features, Religion and Culture, United Kingdom

I’m on holiday. I didn’t mean to be, but I am. I did mean to be here, in this tiny village, on a mountain in Spain. I did mean to be sitting on this hillside, gazing out at olive groves, and pine trees and a blue, blue sky. But what I meant to be doing was write. I was meant, now that I’m freelance, to be doing the kind of writing that means you can actually eat some food and pay some bills. I was meant, in fact, to be writing a little e-book. The trouble is, I didn’t have time to do the research. There are some things that still need research. Proper research, that is, which means meeting people, and talking to people, and looking at things in real life, and not just on Google. The trouble is that to do proper research, you need time. And time is very, very, very hard to find when you’re freelance.

I didn’t actually plan to be freelance. Like all journalists, I knew I probably would be one day. Like all journalists, I knew that newspapers were, and are, and unfortunately soon will be, going down the pan. This makes me more sad than I can say. I believe in journalism. I believe in the kind of journalism I was able to do at The Independent for 10 years, and the kind I did last year looking into the state of nursing, and which got me (though it seems immodest to say it) on the shortlist for a prize that bears a great writer, and journalist’s, name. I think that to look at things, as clearly as you can, and write about them, as clearly as you can, and think about them, as clearly as you can, as Orwell did, and as all good journalists should aim to do, is a good, and proper, and maybe even a noble thing to do. Doing this, or trying to do this, felt to me like a vocation. But a vocation isn’t a hobby. Someone has to pay the rent.

We all know that the clock is ticking. Even Rupert Murdoch knows that the clock is ticking. During the Leveson report, he gave newspapers five to ten years. When I was asked, last autumn, to speak about Leveson at the Battle of Ideas, I tried to think about what newspapers should and shouldn’t do, and what readers should and shouldn’t want, but actually all I could think was this: we are fiddling while Rome burns.

When I saw the play Enquirer, in an office block in the City, it felt like an elegy to an industry that was dying. It probably felt like that because it was. Some of the conversations in it, which were real conversations put into a kind of collage that made up a script, were between people I had worked with, and knew. Some of them, for example, were between Roger Alton, who was one of the nicest editors I ever worked for, and who sent me flowers when I was diagnosed with cancer, and Deborah Orr, who also used to be a colleague, and who is clever, and fierce, and kind. The play talked about Leveson. Of course it talked about Leveson. But most of all it talked about how newspapers were, or soon would be, a relict of the past. The play made me cry, but I think it made a lot of journalists cry. Deborah told me that in Glasgow, where it was first performed, in a building overlooking what used to be the shipyards, almost everyone cried. At the end, she said, the sunset they could see from the window was like a message to a dying industry from one that was already dead.

When I saw Chimerica, a couple of weeks ago, I nearly cried again. The play, which is very, very good, and talks about things plays ought to talk about, like the balance of power between East and West, and between human rights and money, and between the old world and the new, is also, in a way, an elegy to an industry that will soon be lost. It’s set largely in the US, where budgets for newspapers are still much bigger, and more lavish, than they are here. (No wonder the Washington Post needed Amazon profits to keep it going, though the irony of the man who used the internet to kill the high street bailing out the other big industry that’s being killed by the internet can hardly have been lost.) The photographer in the play, who’s trying to revive his career with a story about the “tank man” hero of Tiananmen Square, seems to be shocked that the editor isn’t all that keen to pick up the very, very big costs the story will incur. He’s even more shocked when the editor tells him he has to drop the story, for reasons to do with (Chinese) money, and power. The photographer seemed to think, as many journalists have thought, that it was his right to write the story he wanted to write. I’ve been lucky, over 10 years at The Independent, to write, at least most of the time, the stories (and columns and interviews and features) I’ve wanted to write. But you can only write them for as long as the owner wants to pay.

Newspapers are a rich man’s hobby. They’re a very good way of getting a bit of kudos, and a bit of power. They’ll get you invitations to Downing Street, and opportunities to mix with the great, and what passes for the good. What they won’t do, or hardly ever do, is make you money. The Guardian loses about £40m a year (though last year, apparently, it cut its losses by nearly a third). The Times loses about £40m a year. The Independent loses between £10m and £20m a year. Forty, twenty or even ten million is a lot of money to burn. When people bought newspapers, or, to put it in a more modern way, were happy to “pay for content”, it was bad enough. But how do you try to limit your losses when people expect their “content” – their words, their arguments, their virtual encounters with the great, the good and the reasonably talented – to be as free as the air they breathe?

The answer, it seems, is you don’t. So what you do is cut your costs. You might, for example, want to get rid of all your expensive staff writers. You might decide that “content” is something you can get from a college leaver, for 18, or 19, or 20 grand. You might even decide that the important thing isn’t to get the right words in the right order, but just to get some words – any words – down.

So, we’re losing our jobs. We journalists always knew we’d lose our jobs. We knew it in the way smokers know that sucking a little stick of tobacco gives you cancer. We knew it, but when it happens, it’s still a shock. For me, the week before it all blew up – and I think we can probably say that shouting at the editor so that he threatens to call security does count as things “blowing up” – I had been asked to address a seminar at the House of Commons and present a film for The One Show to coincide with the release of The Francis Report. One moment, I was being asked, by politicians, and TV presenters, and radio presenters, for my opinion on whatever I’d written about that morning. The next moment, I didn’t have a job. The next moment – the next day, to be a little bit more precise – I was telling Harriet Harman, on the phone, while pacing round my study, that I’d been looking forward to doing the interview we’d fixed, for a series on “women and power”, but that it didn’t seem all that appropriate any more, since I didn’t seem to have any power – and that my career as a journalist on a national newspaper seemed to have come to a sudden end.

Since then, I’ve done what freelancers do. I’ve sent a lot of emails. I’ve had a lot of meetings. I’ve discovered, as freelancers apparently often do, that most of your working hours, at least for the first few months of being freelance, are spent trying to get work. You can only do the work – or start to do the work – when the working day ends. Which means, or seems to mean, you end up working pretty much all the time.

It has been an interesting time. I don’t just mean that it’s been interesting in the way the Chinese mean interesting. All journalists know we live in “interesting times”, and most think some boring times would make a nice change. But it really has been interesting. I’ve started reviewing regularly again – fiction, and non-fiction – for the Sunday Times. I’ve been able to do some long-form journalism for the Sunday Times magazine. I’ve written the odd column, for the Guardian, and for the Guardian’s comment website, Comment is Free, but I haven’t had to have an opinion about one of the big issues of the day, once or twice week, as I have done for the past seven years. I’ve worked with some exceptionally nice editors, and I always have what you don’t always have when you’re a staff journalist on a daily paper: the right to say no. But when I’ve looked at the next day’s front pages, for the Sky and BBC News press previews, I haven’t quite been able to decide whether it’s still my world, or not. I know it’s where my heart is. But the body also has to be fed.

Like most journalists, I want to think, and I want to write. Like most journalists, I’ve been lucky to do this for so long. Sure, we can write books, but most writers can’t earn a living any more by writing books. Or at least they can’t unless what they write about is secret codes or sadistic sex. When you’ve worked on a newspaper, and had to deal with some bullying bosses, you’re quite likely to find yourself wanting the home, and the bedroom, to be a sadism-free zone.

We’re meant to be blogging. We’re meant, in other words, to be giving the thing we used to be paid for away, in the ether, for free. Plumbers haven’t yet been told they should mend toilets for free. Builders aren’t yet expected to put in new kitchens for the thrill of being asked. But we’re all meant to be building our “brand”. I don’t know about writers as brands. I suppose a writer can be a brand. But I’d rather think writing was less about brand, and much, much more about “voice”.

So, here I am, freelance and free, on a mountain in Spain. I’m at a writers’ retreat. It’s a very lovely writers’ retreat. It has, as you’ll see from the website, if you look at it (www.oldolivepress.com), a lovely view, a lovely terrace, and a lovely pool. It also has a lovely library. When I looked at the library, and at the 3000 books I was suddenly dying to read, I thought I could be locked in that library and not be too upset if I never had to leave. It also has poets. There’s a poet, Christopher North, who runs the place with his wife, Marisa, and there’s a poet, Tamar Yoseloff, who’s running a course here now. I’m not doing it. I couldn’t, I think, write poetry, even if I tried. I used to run the Poetry Society, and I’ve worked with some of the best poets in the world. I only like good poems, and I’m pretty damn sure that any I wrote would be bad.

I’m not here to write poems. I can’t write the little e-book I was going to write, because I haven’t done the research. What I can do is write a little bit on my blog every day (or almost every day) and gaze at the mountains, and the clouds, and wander round the village, and look at the little houses, painted blue, and green, and pink, and red, and listen to the silence, and remember that sometimes what a recovering journalist needs, more than work, or money, or even a plan for the future, is sunshine, and peace.

This article was originally published on 4 Sept 2013 at Christina Patterson’s blog Independent Thinking.

11 Sep 2013 | Egypt, News and features, Politics and Society

Egypt faced a new phase of uncertainty after the bloodiest day since its Arab Spring began, with nearly 300 people reported killed and thousands injured as police smashed two protest camps of supporters of the deposed Islamist president. (Photo: Nameer Galal / Demotix)

In a widening crackdown on dissent in Egypt since the military takeover on July 3, the Public Prosecutor’s office has reportedly been looking into legal complaints against thirty five rights activists and public figures for allegedly “receiving foreign funding”.

State sponsored Al Ahram newspaper said on its website on Saturday that private citizens had filed lawsuits against the defendants, accusing them of “accepting money from foreign countries including the United States”. According to the Al Ahram story, diplomatic cables leaked by the whistle blower website Wikileaks support the claims.

A judicial source had originally confirmed the story but the prosecutor’s office denied it the following day, calling on journalists to be “more careful and accurate in their reporting”. The defendants meanwhile, believe the ‘mistake’ was deliberate, insisting it was meant to intimidate them and to send a warning message to pro-democracy activists in Egypt to tone down their criticism of the military.

Prosecuting dissenters was common practice under deposed president Hosni Mubarak with regime loyalists often fabricating charges against opponents to silence them. The practice continued under toppled president Mohamed Morsi with his Islamist supporters frequently filing lawsuits against Muslim Brotherhood opponents to intimidate them.

The Al Ahram story triggered an uproar on social media networks Facebook and Twitter, with many internet activists expressing fears that following the brutal security crackdown on Morsi’s Islamist supporters, democracy activists who took part in the January 2011 uprising may be next in line.

Liberal politician Amr Hamzawi denied Al Ahram’s allegations as ‘untrue’ on Twitter, adding that “the campaign of fabrication and distortion must immediately stop”.

Gameela Ismail, a prominent member of the Al Dostour or Constitution Party–who was also among those accused–reacted angrily to what she described on Twitter as “fabricated charges” insisting she would in turn file a lawsuit against those who were “deliberately trying to defame her”.

The rumoured complaints have also fuelled fears of a severe security crackdown on civil society similar to the February 2012 crackdown on NGOs when 43 NGO staffers–including 32 foreigners–were indicted after accusations they were working for unlicensed institutions and receiving illegal funding. The notorious ‘foreign funding’ case dragged on for a year and a half, culminating in convictions for the defendants ranging between one and five years in prison and fines of 1000 Egyptian pounds.

Meanwhile, the arrests of a journalist and a rights lawyer last week has raised concerns about increased rights violations under the emergency law (now in place) allowing for the arbitrary arrests and detention of civilians without charge. Haytham Mohamedein, a leftist lawyer and rights activist was arrested near a military checkpoint in Suez on Thursday and accused of “spreading lies about the military and of belonging to a secret organisation that is planning attacks against the military and state institutions”. While Mohamedein was released the following day, it remains unclear whether the charges against him have been dropped.

Sayed Abu Draa, a North Sinai-based journalist with the independent Al Masry el Youm newspaper who was also arrested last week, has been referred to a military tribunal. He is being accused of “spreading false information about the armed forces and taking photographs of military installations”. A day before his detention, he had slammed the military in a Facebook post for what he described as “misleading information” by the army and the media on the ongoing military operations in Sinai.

In a protest rally organized by journalists outside the press syndicate in downtown Cairo on Monday, the demonstrators called for Abu Draa’s immediate release and for an end to what they described as ” attempts by the authorities to muzzle the press’.

“Freedom of journalists is a red line,” the protesters chanted. “No to military trials for civilians.’

In a crackdown on press freedom since the June 30 rebellion that ousted Mohamed Morsi, the new government this month closed down Al Jazeera Mubasher Misr along with three other networks it perceives as being pro-Islamist. The Administrative Court ruling to shut down the channels was based on charges that included “spreading false rumours and inciting violence.” Government officials claim Al Jazeera was broadcasting without a license –a charge the network denies.

While most state and independent media outlets have clearly aligned themselves with the military-backed government with TV presenters and talk show hosts using strong anti-Muslim Brotherhood rhetoric and advising viewers to support the army in its war against “the terrorists”, a few independent voices refuse to bow under intimidation and threats. They denounce what they describe as “the return of the police state” and are taking a firm stand against censorship.

This article was published on 11 Sept 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

11 Sep 2013 | Americas, Magazine, News and features

A march organized by the National Assembly of Human Rights in Santiago to mark the 40th anniversary of a military coup that ousted President Salvador Allende ended in violence and clashes with police. (Photo: Mario Tellez / Demotix)

The date September 11 has a lot of meanings. For Chile, today marks 40 years since the coup that ushered in 17 years of military dictatorship. This powerful excerpt from Exorcising Terror: the Incredible Unending Trial of General Augusto Pinochet is taken from the winter 2005 edition of Index on Censorship magazine archives.

By Ariel Dorfman

—

It must have been some time in 1974 when I think I first laid eyes on Maria Josefa Ruiz Tagle. She was a baby girl, and if I’m not mistaken she played on the floor of our kitchen in Paris with our son Rodrigo, who was then seven years old, while we chatted with her mother, Monica Espinoza. Angelica says that I am mistaken, that I could not have seen Maria Josefa then because Monica had not come to Europe at that point without her child – and yet that memory burns within me still. I had known Monica’s husband, Eugenio Ruiz Tagle Orrego, only vaguely, just a hello and good-bye a couple of times in the halls of our party’s headquarters (we both belonged to the same revolutionary organisation). Mutual friends keep on telling me that we must have met and talked any number of times, but I can’t for the life of me recall much else, other than trying to squeeze from the memory bag in my head one or two occasions in which we exchanged a joke or two; that’s all I remember of his life. His death, however, was another matter. A civil engineer who came from one of Chile’s most aristocratic families and a dedicated revolutionary since his student days at the Catholic University, the coup had found him in Antofogasta, in the north of the country, acting as general manager of the National Cement Works. He had voluntarily given himself up on 12 September, like so many who had trusted that the military would not defile or denigrate them – and had been killed a month or so later, reportedly in the most savage fashion.

A disturbing rumour had sprung up after his death: that his right-wing father in Santiago had taken his time in pressuring the military to release the wayward offspring, apparently because he thought that nothing much could happen to the young man, given the traditional civility of Chile’s armed forces, or maybe trusting that his son’s blue-blooded heritage would protect him. Which made it even more heartbreaking when his mother demanded that Eugenio’s tightly sealed coffin be opened and discovered his body and face mutilated almost beyond recognition. But I always wondered if these reports of his father’s guilty detachment and subsequent intolerable loss did not constitute a fabrication of the sort that often circulate in uncertain and violent times, an attempt by a repressed community to forge a story of how the murder of a rebellious son awakens a conservative progenitor to the true evil of a regime he helped to bring into being.

What was no fabrication, however, was how that death had devastated the family, and you could see it in the deep well of sorrow that Monica seemed to be floating in when we met her in Paris almost a year after the execution of her husband. And yet, at the same time, there was an unexpected purity in her gaze as I recall it, as if she had decided not to give fate the satisfaction of seeing her cry, as if all the tears had dried up inside her instead of coming out. Or was it a quiet resilience? – a decision she seemed to have made that she was going to get on with life, no matter how hard that might be, for the sake of the baby, but also in the name of her dead love, who would not have wanted the murder of his body to have murdered her future. So I was not entirely surprised when I heard, some months later, that she had settled into a stable relationship with Jose Joaquin Brunner, a friend of hers and Eugenio’s from way back. Brunner, whom I was also close to, was at the time working on his doctorate at Oxford and would become, upon his return to Chile a few years later with Monica and Maria Josefa, one of the country’s most prominent intellectuals. But perhaps more essential to Monica, Jose Joaquin grew into the role of Maria Josefa’s daddy, bringing her up as if she were his own child.

The little girl was told from her early age that her biological father, Eugenio, had died in front of a firing squad, but no other details were forthcoming. She conjured up, Maria Josefa wrote many years later, a sort of romantic scene – a death occasioned by a diffuse group of men, none of whom was identifiably responsible, perhaps a way of keeping that violence done to her father from overwhelming and poisoning her life, by not making her wonder about who was personally responsible for that homicide. She always sensed, nevertheless, that underneath the silence surrounding and covering that remote death, there lurked something more dreadful, some secret terror that was all the more fearful because nobody dared to name it. And then, one day, when she was twelve, a strange hunch led her to probe and explore what might lie behind a photograph in her grandmother’s house, a picture which showed Maria Josefa herself at around two years of age taking a bath in a small tub. Was it the clean water in which she was bathing in the picture that provoked her to undo the frame that held it and go beyond the false innocence of that child she had once been? Perhaps, because what she found were three pages hidden by her grandmother and written by two of her father’s friends who had witnessed the way he had been treated before he died, witnesses who had been tortured themselves but who had, by a miracle, survived instead of being killed by the Caravan of Death. Reading those words from the past, Maria Josefa found out that Eugenio had not been shot by a firing squad, but – to use her own words – ‘he was missing an eye. They had carved out his nose. His face was deeply burnt in many places. His neck had been broken. Stabs and bullet wounds. The bones broken in a thousand parts. They had torn the nails from his hands and from his feet. And they had told him that they were going to kill me and my mother’.

But she said nothing. She kept those words, those images, inside. Like the country inside. Like the country itself.

Many years later, in 1999, when she had Lucas, her first baby – at the age of 26, the age her father had reached upon his death – when she held the baby in her arms and realised that her father had also been able to hold her and get to know her, she burst into tears one morning and felt the irresistible need to write to her father, to tell her story, what it meant to be the child not only of a murdered man but of a country that did not want to confront and name that death. She denounced how everything around her had been built so she and everyone else would not have to look the past in the face. Built, she said, so that people would never have to go to sleep every night feeling afraid.

Still, however, she kept those intimate words to herself. Until, a year and a half later, in November 2000, when Eugenio’s body was exhumed from the Antofagasta cemetery and taken to the Wall of Memory in Santiago for a second burial. Then she allowed an actor publicly to read out, on that occasion, the words she had written to her father. For the tears that have been kept hidden all these years to come out, the tears that I had not been able to see when we sat with her mother Monica in that kitchen in Paris and I watched the fatherless child playing, for that to happen, first Pinochet had to be stripped of his immunity and Eugenio’s name had to be cleared – he was not a terrorist but a victim, he was not a criminal but a hero, and his death was terrible but had not been entirely in vain as it had come back to haunt the man who had ordered it. First Eugenio had to come back from the dead. Then his daughter could come out into the light of day.

But that is not the end of the story. When you drag something out from its hiding place, other things emerge, one thing leading to another. Eugenio Ruiz Tagle still had one more service to perform for his family and his friends and his country.

When Judge Guzman placed General Pinochet under house arrest at the end of January 2001, his lawyers immediately appealed – insisting that their client was innocent, that there was no proof that he had known about any of the deaths of the Caravan of Death. One week later, on February 7, the online newspaper El Mostrador (these sorts of journals are the only really free sites in Chilean print media) published the most damning document yet in the whole case. Back in 1973, Pinochet’s justice minister – probably because of Ruiz Tagle’s family connections – had informed the Commander in Chief of the Army of the young man’s torture and extrajudicial execution by the officers from the Caravan of Death. In his own handwriting, Pinochet answered the minister that he was to deny the facts and conceal them, instructing him to say: ‘Mr. Ruiz Tagle was executed due to the grave charges that existed against him. [Say that] there was no torture according to our information.’ Needless to say, any possible investigation into that death had been quashed.

This piece of news occasioned yet another revelation the next day in the same online newspaper. Carlos Bau, an accountant at the Cement Works where Eugenio had been general manager and who had given himself up to the authorities that same 12 September, told the story of Ruiz Tagle’s daily torture at the Air Force Base of Cerro Moreno in Antofagasta during the month that preceded his execution: the soldiers had wanted the prisoners to confess that they had weapons and explosives (Pinochet’s subordinates were trying to assemble a justification for the repression their commander in chief had unleashed, proof that there was a war and that the enemy was armed and dangerous). It turned out that, far from protecting him, Ruiz Tagle’s surnames had made his tormentors pick him out for special treatment – maybe to teach him a lesson, maybe because they had class resentments of their own, maybe because a Ruiz Tagle should have known better than to associate with the Allendista riffraff. Whatever the reasons, he was always the first to be beaten every time there was a session, constantly mocked and kicked and cut – and, like his wife a year later in Paris, like his daughter throughout most of her life, Eugenio had not let a cry out, had kept what was he was feeling inside. But Bau added one more detail that had not up until that moment been public knowledge in Chile: the identity of the officer who had started the beating, who had begun it all by landing Eugenio a kick in the genitals as an introduction to what was to await him in the days ahead. It was Lieutenant Herna´n Gabrielli Rojas. Who happened to be the present acting commander in chief of the Chilean air force. The same man.

‘Are you sure?’ the journalist asked Bau.

‘Absolutely sure.’

And in the next days, Bau’s identification was confirmed by several other witnesses. Herna´n Vera and Juan Ruiz and another victim, an officer called Navarro, who added that he had also seen Gabrielli torturing a 14-year-old boy.

General Gabriielli’s response on 12 February was not only to proclaim his innocence but also to announce that he was suing Bau and the others for libel – invoking a clause in the Law of National Security that shields a commander in chief from slander. The charges were subsequently dismissed (‘We weren’t slandering him,’ Bau said, ‘we were just telling the truth about him’) and, later in the year, in spite of ferocious resistance from the air force, Gabrielli was forced to step down from his post.

Another side effect of the trial of General Pinochet. And another lesson to be learned.

Because terror is not conquered in one revelatory flash. It is a slow, zigzag process, just like memory itself. Let me make myself clearer: I had read the name Gabrielli as the tormentor of Ruiz Tagle back in 1976 or 1977, when Carlos Bau arrived in Holland (where our family had just moved from Paris). He had already served three years of a 40-year prison sentence which had been commuted into 20 years of banishment. Carlos had no qualms in recounting his terrifying story – though what I recalled above all of that conversation afterward was an image that surged into my head and stayed with me through the years, my realisation that when somebody has been tortured it is as if for the rest of their life they will be wearing sunglasses behind their eyes.

Click here to subscribe to Index on Censorship magazine, or download the app here

This article was originally published in the winter 2005 edition of Index on Censorship magazine.

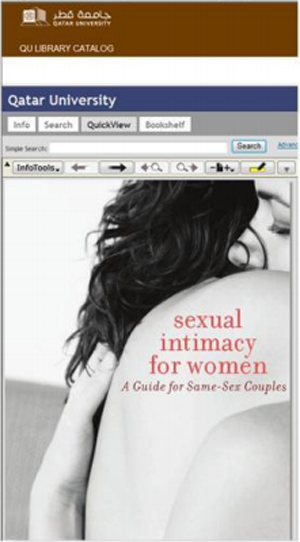

A group of students at the University of Qatar have started a petition to remove “inappropriate” books from the university library.

A group of students at the University of Qatar have started a petition to remove “inappropriate” books from the university library.