7 Jan 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, European Union, News and features, Politics and Society, Religion and Culture

(Photo: Anatolii Stepanov / Demotix)

This article is part of a series based on our report, Time to Step Up: The EU and freedom of expression

Media concentration in the EU poses a significant challenge. The media in the EU is significantly more concentrated than in North America, even when taking into consideration explanations of population, geographical size and income. Even by global standards, media concentration in the EU is high.

Another challenge arises from national media regulation, which may both fail to protect plurality and, allow an unnecessary and unacceptable amount of political interference in the way the media works. While the EU does not have an explicit competency to intervene in all matters of media plurality and media freedom, it is not neutral in this debate. A number of initiatives are underway to help better promote media freedom, and in particular media plurality. Free expression advocates, including Index, welcome the fact that the EU is taking the issue of media freedom more seriously.

Media regulation

Across the European Union, media regulation is left to the member states to implement, leading to significant variations in the form and level of media regulation. National regulation must comply with member states’ commitments under the European Convention on Human Rights, but this compliance can only be tested through exhaustive court cases. While the European Commission has, in the past, tended to view its competencies in this area as being limited due to the introduction of the Charter of Fundamental Rights into EU primary law, the Commission is looking at its possible role in this area. In part, the Commission is acting upon the guidance of the European Parliament, which has expressed significant concerns over the state of media regulation, and in particular with regard to Hungary, where regulation has been criticised for curtailing freedom of expression.

The national models of media regulation across Europe vary significantly, from models of self-regulation to statutory regulation. These models of regulation can impact negatively on freedom of expression through the application of unnecessary sanctions, the regulator’s lack of independence from politicians and laws that create a burdensome environment for online media. Statutory regulation of the print and broadcast media is increasingly anachronistic, raising questions over how the role of journalist or broadcaster should be defined and resulting in a general and increasing confusion about who should be covered by these regulatory structures, if at all. Frameworks that outline laws on defamation and privacy and provide public interest and opinion defences for all would provide clarify for all content producers. In the majority of countries, the broadcast media is regulated by a statutory regulator (due to a scarcity of analogue frequencies that required arbitration in the past), yet, often, the print media is also regulated by statutory bodies, including in Slovenia, Lithuania, Italy; or regulated by specific print media laws and codes, for example in Austria, France, Sweden and Portugal. As we demonstrate below, many EU member states have systems of media regulation that are overly restrictive and fail to protect freedom of expression.

In many EU member states, the system of media regulation allows excessive state interference in the workings of the media. Hungary’s system of media regulation has been criticised by the Council of Europe, the European Parliament and the OSCE for the excessive control statutory bodies exert over the media. The model of “co-regulation” was set up in 2010 through a new comprehensive media law[1], culminating in the creation of the National Media and Infocommunications Authority, which was given statutory powers to fine media organisations up to €727,000, oversaw regulation of all media including online news websites, and acts as an extra-judicial investigator, jury and judge on public complaints. The president of the Media Authority and all five members of the Media Council were delegated exclusively by Hungary’s Fidesz party, which commanded a majority in Parliament. The law forced media outlets to provide “balanced coverage” and had the power to fine reporters if they didn’t disclose their sources in certain circumstances. Organisations that refused to sign up to the regulator faced exemplary fines of up to €727,000 per breach of the law. While the European Commission managed to negotiate to remove some of the most egregious aspects of the law, nothing was done to rectify the political composition of the media council, the source of the original complaint to the Commission.

Hungary is not the only EU member state where politicians have excessive influence over media regulators. In France, the High Council for Broadcasting (CSA), which regulates TV and radio broadcasting, has nine executives appointed by presidential decree, of which three members are directly chosen and appointed by the president, three by the president of the Senate, and three by the president of the National Assembly. According to the Centre for Media and Communication Studies, this system for appointing authorities has the fewest safeguards from governmental influence in the EU.

Many countries have statutory underpinning of the press, which includes the online press, including Austria, France, Italy, Lithuania, Slovenia and Sweden. Some statutory regulation can provide freedom of expression protections to those who voluntarily register with the regulatory body (for instance in Sweden), but in many instances, the regulatory burden and possibility of fines for online media can chill freedom of expression.

The Leveson Inquiry in the UK was established after the extent of the phone-hacking scandal was discovered, revealing how journalists had hacked the phones of victims of crime and high profile figures. Lord Justice Leveson made a number of recommendations in his report, including the statutory underpinning of an “independent” regulatory body, restrictions to limit contact between senior police officers and the press that could inhibit whistleblowing, and exemplary damages for publishers who remain outside the regulator. Of particular concern was the notion of statutory unpinning by what was claimed to be an “independent” and “voluntary” regulator. By setting out the requirements for what the regulator should achieve in law, it introduced some government and political control over the functioning of the media. Even “light” statutory regulation can be revisited, toughened and potentially abused. Combined with exemplary damages for publishers who remained outside the “voluntary” regulator (damages considered to be in breach of Article 10 of the European Convention of Human Rights by three eminent QCs), the Leveson proposals were damaging to freedom of expression. The situation was compounded by the attempt by a group of Peers in the House of Lords to exert political pressure on the government to regulate the press, potentially sabotaging much-needed reform of the archaic libel laws of England and Wales. This resulted in the government bringing in legislation through the combination of a Royal Charter (the use of the Monarch’s powers to establish a body corporate) and by adding provisions to the Crime and Courts Act (2013) that established the legal basis for exemplary damages. It is arguable that the Leveson proposals have already been used to chill public interest journalism.

In part a response to the dilemma posed by Hungary, but also to wider issues of press regulation raised by the Leveson Inquiry in the UK, vice president of the Commission Neelie Kroes has overseen renewed Commission interest in the area of media regulation. This interest builds upon the possibility of the Commission using new commitments introduced through the Charter of Fundamental Rights into EU primary law, such as Article 11 of the Charter, which states: “The freedom and pluralism of the media shall be respected.” The Commission is now exploring a variety of options to help protect media freedom, including funding the establishment of the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom and the EU Futures Media Forum. In October 2011, Kroes founded a High Level Group on Media Freedom and Pluralism to look at these issues in more detail. The conclusions were published in January 2013.

Many of the recommendations of the High Level Media Group are useful, in particular the first recommendation: “The EU should be considered competent to act to protect media freedom and pluralism at State level in order to guarantee the substance of the rights granted by the Treaties to EU citizens”. Yet some of the High Level Group’s conclusions do not provide a solution to questions of appropriate legislation within the EU. The group called for all member states to have “independent media councils” that are politically and culturally balanced with a socially diverse membership and have enforcement powers including fines, the power to order printed or broadcast apologies and, particularly concerning, the power to order the removal of (professional) journalistic status.[2] Political balance could be interpreted as political representation on the media councils, when the principle should be that the media is kept free from political interference. This was an issue raised in particular by Hungarian NGOs during the consultation. Also of particular concern is the suggestion that the European Commission should monitor the national media councils with no detail as to how the Commission is held to account, or process for how national media organisations could challenge bad decisions by the Commission. The Commission is awaiting the results of a civil society consultation. Depending on the conclusions of the Commission, stronger protections for media freedom may be considered when a state clearly deviates from established norms.

[1]Act on the Freedom of the Press and the Fundamental Rules on Media Content (the “Press Freedom Act”) and the Media Services and Mass Media Act (or the “Media Act”)

[2] p.7, High Level Media Group on Media Freedom and Pluralism

6 Jan 2014 | Digital Freedom, India, News and features, Politics and Society

Social media played a significant part in Arvind Kerjiwal’s successful campaign to become chief minister of New Dehli. He is pictured here addressing auto drivers at a protest in June last year (Image: Rohit Gautam/Demotix)

Much has been written about the influence of social media in the upcoming Indian national elections, expected to take place in mid 2014.

While the two major political parties, the Congress and BJP, have invested in social media cells, the larger consensus is that the internet is still largely an urban phenomenon, and therefore, somehow, not important. According to the latest TRAI figures, rural tele-density still stands at 42%. However, the flip side is that urban tele-density, currently at 144.28%, has allowed the cities to become a litmus test of what could happen if the population was able to access the internet, therefore social media, during election time.

Against the backdrop of social media giving the average citizen a voice to express often ignored opinions, came the anti-corruption protests of 2011, led by Gandhian Anna Hazare and his commander-in-chief, former bureaucrat Arvind Kejriwal. As the two spearheaded a campaign to fight against the injustices meted out to the common man through an oppressive political system, and fought for an anti-corruption law to be passed, they found an onslaught of support over social media by the middle class. Even the TV news channels got caught up in the noble theatrics, keeping the cameras live at Anna Hazare’s hunger strike in the capital, attracting more viewers, and also more supporters for their cause.

Two years later, the bill has been passed – but Team Anna, as it was popularly called, split into two factions The first remains under the leadership of Anna Hazare, and has dissipated into the background. The second, however, has only grown in size and stature. Arvind Kejriwal, in perhaps the most maverick of moves, sits in the capital of India today as its chief minister. This, with a groundswell of support not just from the haggard residents of New Delhi, but seemingly growing support from all over the country. Many factors have contributed to this rise; however, one can certainly identify the role of social and citizen media in shaping this particular election, especially when it comes to Delhi’s middle class.

Kejriwal formally formed the Aam Aadmi Party in November 2012, which translated means the ‘Common Man Party’. They decided to contest the 2013 Delhi elections, with Kejriwal directly taking on three time Congress Chief Minister, Sheila Dixshit, in her constituency. He defeated her.

The Aam Aadmi Party today has 1, 137, 873 likes on Facebook. People can donate to the party online, and follow its leaders on Twitter. What’s more, in a clear and concise website, AAP lists out its manifesto, explanations about its constitution and decisions and even an internal complaints committee. It has a video link, a blog, and even an events page so that people can join in. As it gears up for the 2014 national elections, AAP is also inviting nominations for candidates online. This is unheard of in Indian politics, where politicians are born out of birthright or bribes.

As elections in Delhi were underway, Indian media reported that Kejriwal had admitted to learning from Barack Obama’s social media strategy of 2008, which many believe helped him win the White House. Seven thousand dedicated volunteers consisting of students, workers, people on sabbatical from their jobs, and even retired government officials joined to help AAP rise to power. They collected roughly $1.8 million USD for the campaign in 2013. After the campaign was over, analysts revealed the success of AAP with first time voters: AAP’s online coordinators talk of reaching 3.5 million people just before voting day with an app called Thunderclap, which sits on your Facebook page and tells you to go vote. There seemed to be some sort of social media pressure to be trendy and go vote when it came to the youth of Delhi. However, when it came to its low-income group supporters, AAP did not rely on the power of social media, but implemented a door-to-door strategy which would work in that demographic.

AAP has not been without its share of controversies, the most recent of which was deftly handled through opinion polling over telephone and social media. Kejriwal had announced that in the cause of a hung election in Delhi, his party would absolutely not take the support of either the BJP or Congress to form government. The situation played out exactly as they hoped it wouldn’t. So as to not go back on his word, but still have the option of forming government, AAP decided to ask the people what to do. Suddenly, the people of Delhi could vote in various ways, advising Kejriwal on what he should do. After the polls closed, Kejriwal declared that overwhelmingly, AAP supporters wanted him to form government, which he did. As expected, the BJP has alleged that the “so-called referendum” was actually members of the Congress Party spamming the poll to ensure AAP took Congress support to form government, thereby letting the defeated Congress government regain a position of power.

The takeaway from Kejriwal’s success is that social media buzz, leading to (or perhaps caused by) the mainstream media coverage, has effectively resulted in a small time activist now sharing prime time space with Prime Ministerial candidates like the Congress’s scion Rahul Gandhi and the BJP’s Narendra Modi. In the virtual world, the scales are shifting. The Times of India reports that television channels and social media immediately latched on to AAP leader Arvind Kejriwal as the new ‘hero’ who has since then been eating into Modi’s turf – that of the ‘public mind space’. In this war for public attention, Kejriwal seems to be gaining ground at Modi’s cost.

The Aam Aadmi Party and Arvind Kejriwal have certainly cornered the market on becoming heroes for promises made, aided by a masterful communication strategy. But there is more to this. Indians – residents of New Delhi – finally were able to participate in the interactive social media political campaign that they had previously only read about. The promise of an active democracy where the political leaders don’t just dictate terms but actually solicit and respond to the common man is too tempting an offer to ignore. In his first few days in office, Delhi’s new chief minister was unable to come in to the office, and almost comically tweeted that he was held back because of “loose motions.” The joke goes that perhaps some filters are necessary on social media!

However, irrespective of whether AAP delivers on all its promises or is somehow muscled out of office in a few months, it has proven something to all Indian media watchers. Social media buzz has helped in shaping the agenda for India’s largest and most important city, making a newly formed political party into a serious player in just over a year. This is significant as India has over 360 political parties, and space is limited on the national stage. With a few months to go until the national elections, one can expect more articles in the newspapers, listing out how other politicians have suddenly found the value of interacting with the common man over Facebook and Twitter, helpfully answering questions and taking feedback.

This article was p0sted on 6 Jan 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

6 Jan 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, News and features

In France, Bob Dylan is being officially investigated for “incitement to hatred” against Croats for comparing their relationship to Serbs with that between Nazis and Jews in an interview.

This article is part of a series based on our report, Time to Step Up: The EU and freedom of expression.

Freedom of information

Freedom of information is an important aspect of the right to freedom of expression. Without the ability to access information held by states, individuals cannot make informed democratic choices. Many EU member states have failed to adequately protect freedom of information and the Commission has been criticised for its failure to adequately promote transparency and uphold its commitment to freedom of information.

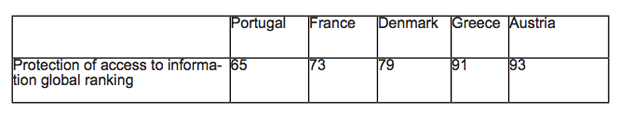

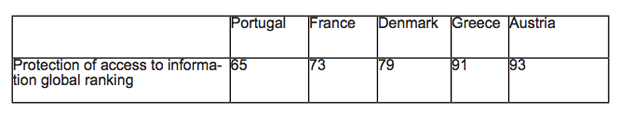

When it comes to assessing global protection for access to information, not one European Union member state ranks in the list of the top 10 countries, while increasingly influential democracies such as India do. Two member states, Cyprus and Spain, are still without any freedom of information laws. Of those that do, many are weak by international standards (see table below).

In many states, the law is not enforced properly. In Italy, public bodies fail to respond to 73% of requests.

The Council of Europe has also developed a Convention on Access to Official Documents, the first internationally binding legal instrument to recognise the right to access the official documents of public authorities. Only seven EU member states have signed up the convention.

Since the Lisbon Treaty came into force, both member states and EU institutions are both bound by freedom of information commitments. Article 42 (the right of access to documents) of the European Charter of Fundamental Rights now recognises the right to freedom of information for EU documents as a fundamental human right Further, specific rights falling within the scope of freedom of information are also enshrined in Article 41 of the Charter (the right to good administration).

As a result, the European Commission has embedded limited access to information in its internal protocols. Yet, while the European Parliament has reaffirmed its commitment to give EU citizens more access to official EU documents, it is still the case that not all EU institutions, offices, bodies and agencies are acting on their freedom of information commitments. The Danish government used their EU presidency in the first half of 2012 to attempt to forge an agreement between the European Commission, the Parliament and member states to open up public access to EU documents. This attempt failed after a hostile response from the Commission. Attempts by the Cypriot and Irish presidencies to unblock the matter in the Council also failed.

This lack of transparency can and has impacted on public’s knowledge of how decisions that affect human rights have been made. The European Ombudsman, P. Nikiforos Diamandouros, has criticised the European Commission for denying access to documents concerning its view of the United Kingdom’s decision to opt out from the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights. In 2013, Sophie in’t Veld MEP was barred from obtaining diplomatic documents relating to the Commission’s position on the proposed Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement (ACTA).

Hate speech

Across the European Union, hate speech laws, and in particular their interpretation, vary with regard to how they impact on the protection for freedom of expression. In some countries, notably Poland and France, hate speech laws do not allow enough protection for free expression. The Council of the European Union has taken action on combating certain forms and expressions of racism and xenophobia by promoting use of the criminal law within nation states in its 2008 Framework Decision. Yet, the Framework Decision failed to adequately protect freedom of expression in particular on controversial historical debate.

Throughout European history, hate speech has been highly problematic, from the experience and ramifications of the Holocaust through to the direct incitement of ethnic violence via the state run media during wars in the former Yugoslavia. However, it is vital that hate speech laws are proportionate in order to protect freedom of expression.

On the whole, the framework for the regulation of hate speech is left to the national laws of EU member states, although all member states must comply with Articles 14 and 17 of the ECHR.[1] A number of EU member states have hate speech laws that fail to protect freedom of expression –- in particular in Poland, Germany, France and Italy.

Article 256 and 257 of the Polish Criminal Code criminalise individuals who intentionally offend religious feelings. The law criminalises public expression that insults a person or a group on account of national, ethnic, racial, or religious affiliation or the lack of a religious affiliation. Article 54 of the Polish Constitution protects freedom of speech but Article 13 prohibits any programmes or activities that promote racial or national hatred. Television is restricted by the Broadcasting Act, which states that programmes or other broadcasts must “respect the religious beliefs of the public and respect especially the Christian system of values”. In 2010, two singers, Doda and Adam Darski, where charged with violating the criminal code for their public criticism of Christianity.[2] France prohibits hate speech and insult, which are deemed to be both “public and private”, through its penal code[3] and through its press laws[4]. This criminalises speech that may have caused no significant harm whatsoever to society, which is disproportionate. Singer Bob Dylan faces the possibility of prosecution for hate speech in France. The prosecutor’s office in Paris confirmed that Dylan has been placed under formal investigation by Paris’s Main Court for “public injury” and “incitement to hatred” after he compared the relationship between Croats and Serbs to that of Nazis and Jews.

The inclusion of incitement to hatred on the grounds of sexual orientation into hate speech laws is a fairly recent development. The United Kingdom’s hate speech laws contain specific provisions to protect freedom of expression[5] but these provisions are not absolute. In a landmark case in 2012, three men were convicted after distributing leaflets in Derby depicting a mannequin in a hangman’s noose and calling for the death sentence for homosexuality. The European Court of Human Rights ruled on this issue in its landmark judgment Vejdeland v. Sweden, which upheld the decision reached by the Swedish Supreme Court to convict four individuals for homophobic speech after they distributed homophobic leaflets in the lockers of pupils at a secondary school. The applicants claimed that the Swedish Supreme Court’s decision to convict them constituted an illegitimate interference with their freedom of expression. The ECtHR found no violation of Article 10, noting even if there was, the interference served a legitimate aim, namely “the protection of the reputation and rights of others”.

The widespread criminalisation of genocide denial is a particularly European legal provision. Ten EU member states criminalise either Holocaust denial, or the denial of crimes committed by the Nazi and/or Communist regimes. At EU level, Germany pushed for the criminalisation of Holocaust denial, culminating in its inclusion from the 2008 EU Framework Decision on combating certain forms and expressions of racism and xenophobia by means of criminal law. Full implementation of the Framework Decision was blocked by Britain, Sweden and Denmark, who were rightly concerned that the criminalisation of Holocaust denial would impede historical inquiry, artistic expression and public debate.

Beyond the 2008 EU Framework Decision, the EU has taken specific action to deal with hate speech in the Audiovisual Media Service Directive. Article 6 of the Directive states the authorities in each member state “must ensure by appropriate means that audiovisual media services provided by media service providers under their jurisdiction do not contain any incitement to hatred based on race, sex, religion or nationality”.

Hate speech legislation, particularly at European Union level, and the way this legislation is interpreted, must take into account freedom of expression in order to avoid disproportionate criminalisation of unpopular or offensive viewpoints or impede the study and debate of matters of historical importance.

[1] ‘Article 14 – discrimination’ contains a prohibition of discrimination; ‘Article 17 – abuse of rights’ outlines that the rights guaranteed by the Convention cannot be used to abolish or limit rights guaranteed by the Convention.

[2] The police charged vocalist and guitarist Adam Darski of Polish death metal band Behemoth with violating the Criminal Code for a performance in 2007 in Gdynia during which Darski allegedly called the Catholic Church “the most murderous cult on the planet” and tore up a copy of the Bible; singer Doda, whose real name is Dorota Rabczewska, was charged with violating the Criminal Code for saying in 2009 that the Bible was “unbelievable” and written by people “drunk on wine and smoking some kind of herbs”.

[3] Article R625-7

[4] Article 24, Law on Press Freedom of 29 July 1881

[5] The Racial and Religious Hatred Act 2006 amended the Public Order Act 1986 by adding Part 3A[12] to criminalising attempting to “stir up religious hatred.” A further provision to protect freedom of expression (Section 29J) was added: “Nothing in this Part shall be read or given effect in a way which prohibits or restricts discussion, criticism or expressions of antipathy, dislike, ridicule, insult or abuse of particular religions or the beliefs or practices of their adherents, or of any other belief system or the beliefs or practices of its adherents, or proselytising or urging adherents of a different religion or belief system to cease practising their religion or belief system.”

3 Jan 2014 | About Index

[gravityform id=”1″ name=”Keep Up To Date” ajax=”true”]