6 Feb 2014 | Indonesia, News and features, Politics and Society, Religion and Culture

(Photo illustration: Shutterstock)

Listening to Indonesian politicians campaigning for this year’s elections you could be forgiven for thinking that freedom of religion is not a problem in the country with the world’s largest Muslim population and that all is well when it comes to interfaith relations.

You couldn’t be more wrong.

Just because freedom of religion rarely makes an election theme doesn’t mean that everything is all right. And don’t take the word of President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono either, who in May received an award from the New York-based Appeal of Conscience Foundation for promoting “religious tolerance”.

Speak instead with the followers of Ahmadiyah, the Muslim Shias, various Christian denominations and other minority religious communities. They will tell you, mostly in private, of their fears along with stories of persecution and harassment, sometimes involving violence by hard-line Islamic groups, and often with the tacit approval of the government.

To religious minorities, the fact that no politician has bothered to take up the issue and that the majority of Sunni Muslims are keeping silent, Indonesia is anything but tolerant. The problem is growing due to this official and public denial in Indonesia that it even exists.

The religious minorities also know they are missing out on the opportunity to make their case before the nation during this election year because most politicians would consciously avoid talking about religious freedom in their campaigns.

Indonesians will be voting twice this year, first for their representatives in April and second for their president in July. A new government will be installed October.

This will be the nation’s fourth democratic elections since it deposed strongman Suharto in 1998. Indonesia has since won accolades as one of the few successful countries to make the transition from authoritarianism to democracy.

Its leaders often boast that Indonesia is the world’s third largest democracy after India and the United States, and the largest democracy among Muslim-majority countries. Religious tolerance has even been touted as one of the recipes for the country’s success.

Indonesian diplomats have been involved in establishing and promoting interfaith dialogues at bilateral, regional and international levels. In August, Indonesia will be sure to showcase its democracy and religious tolerance when it hosts the annual meeting of the UN Alliance of Civilizations.

Indonesia’s democracy, however, has one big flaw: It is quickly turning into a simple majority rule, and this means that when it comes to religious issues, the voices of religious minorities are drowned out by the voice, or even the silence, of the Muslim majority.

While religious moderation still prevails, religious minorities feel that often the Muslim majority stretches their tolerance too far to include tolerating religious intolerance. Their silence in the face of reported religious persecution is disturbing.

Muslims, predominantly Sunnis, make up about 86% of Indonesia’s population of 250 million.

Religious minorities coming under persecution have learned that sometimes it is better to keep silent and not draw too much public attention to themselves. In some instances, those who have spoken out against their ill-treatment have earned the wrath of more Muslims and the government.

Typically the victims were blamed and came off worse. Some Ahmadiyah, Shiah and Christian leaders have gone to jail on various pretexts. Charges have ranged from blasphemy for preaching their beliefs to building permit violations in connection to places of worship. Worst of all, some religious minorities have been targeted for disturbing the peace by their mere existence.

Hundreds, if not thousands, of Ahmadis have been lingering in makeshift shelters for years in East Java and West Java because their homes, schools and mosques have been vandalized or even razed to the ground by radical Islamic groups.

Dozens of Shia followers in East Java are living in shelters after they were hounded out of their village in 2012. The provincial government has told them that they would be able to return on condition of renouncing their Shia beliefs and “return to the right path”.

A Shia leader last year saw his jail term doubled to four years by the High Court and later upheld by the Supreme Court for spreading his teachings, something that the court considered blasphemous to the “real Islam”. Two men who led the mob to vandalize his house and attack his followers in Sampang received eight months imprisonment.

This is a repetition of the 2011 controversial court verdicts that sentenced an Ahmadiyah follower, whose house in the Cikeusik village in West Java was raided in a fatal attack, to six months imprisonment, the same or higher than what the assailants got.

Last year also saw Palti Panjaitan, a priest with the HKBP Filadelfia Christian church in Bekasi, just outside Jakarta, tried in a court for “assailing” a Muslim leader who had joined a mob to taunt and harass him and the Church followers outside his church.

This has resulted in the congregations of HKBP Filadelfia, and that of GK Yasmin Christian church in Bogor, another township adjacent to Jakarta, conducting their Sunday prayers outside the Presidential Palace in Jakarta every week in protest of the government’s failure to protect and uphold their rights to conduct services.

President Yudhoyono has obviously not heard their prayers yet.

In both cases, the local government has refused to reopen their churches in defiance of Supreme Court rulings that supported the presence of the church and the right of the people to conduct prayers there.

Religious minorities in Indonesia may have given up hope on President Yudhoyono helping their case. But at least they have some comfort knowing that, come October, a new president will be in power: Yudhoyono cannot return for a third term.

Freedom of religion may not be an election issue, but no doubt the new president will be reminded that their oath of office includes a pledge to uphold the constitution, which clearly stipulates an obligation to guarantee and protect freedom of religion.

Democracy still gives some hope.

This article was originally published on 6 February 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

5 Feb 2014 | News and features, Politics and Society, United Kingdom

Dieudonné M’bala M’bala has been banned from entering the UK. The French comedian has long been a controversial figure in his home country, but he became internationally known when West Bromwich Albion striker Nicolas Anelka celebrated a goal with the now infamous quenelle — a sort of inverted nazi salute created by Dieudonné, his friend.

Dieudonné argues he is simply standing up to the establishment, and that the quenelle is an anti-establishment gesture. The facts tell a different story. He has made a number of clearly antisemitic comments, and has been convicted in France of inciting racial hatred.

Dieudonné was set to visit the UK to support Anelka, who has been charged by the Football Association over the incident, and faces a minimum five-match ban. As a colleague pointed out, it’s unclear how, exactly, further links to Dieudonné would help Anelka, but that is now beside the point, as he has been “excluded from the UK at the direction of the Secretary of State”. A letter from the Home Office, obtained by Swiss newspaper Tages-Anzeiger, states that he should not be allowed to board carriers to the UK. If he gets as far as the border, he’ll be turned away at the door, as it were.

But Dieudonné is not alone. Over the years, a number of controversial speakers, covering pretty much the entire spectrum of extremist ideologies, have been banned from entering the UK. The reasons given from the Home Office are almost always along the vague lines of the person in question not being “conducive to the public good”. Below are some the most high-profile cases.

Pamela Geller and Robert Spencer

(Image: Mark Tenally/Demotix)

The American “counter-jihadists” were last May invited to speak at an EDL rally in Woolwich, London, at the scene of the brutal murder of Drummer Lee Rigby. However, they both received letters from the Home Office, informing them that based on past statements they were barred from entering the UK. One of Geller’s comments highlighted was: “Al-Qaeda is a manifestation of devout Islam… It is Islam.” In a joint statement, they declared that “…the British government is behaving like a de facto Islamic state. The nation that gave the world the Magna Carta is dead”.

Geert Wilders

(Image: Frederik Enneman/Demotix)

In 2009, leader of the far-right Dutch Party for Freedom was set to travel to the UK to show his controversial film Fitna — which has been widely labelled as Islamophobic — in the House of Lords. Despite being told by the Home Office before travelling the he was barred from entry because his views “threaten community harmony and therefore public safety”, he still flew to Heathrow, where he was eventually stopped at the border. “Even if you don’t like me and don’t like the things I say then you should let me in for freedom of speech. If you don’t, you are looking like cowards,” was his message to British authorities at the time. The decision was later overturned.

Fred Phelps and Shirley Phelps-Roper

(Image: Wikimedia Commons)

The father and daughter, both members of the infamous Westboro Baptist Church — know, among other things, for picketing funerals — were planning on coming to Leicester to protest against a play about a man killed for being gay. The UK Border Agency said at the time: “Both these individuals have engaged in unacceptable behaviour by inciting hatred against a number of communities.”

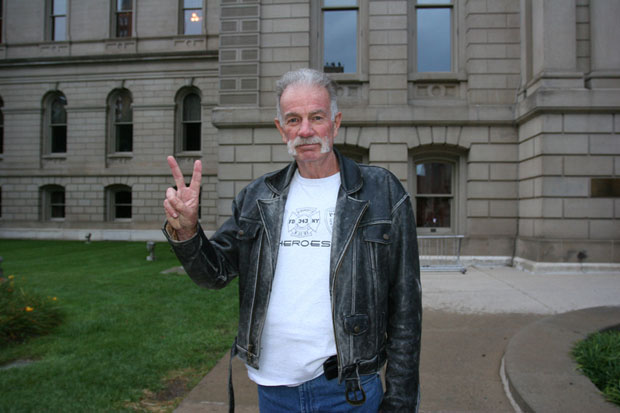

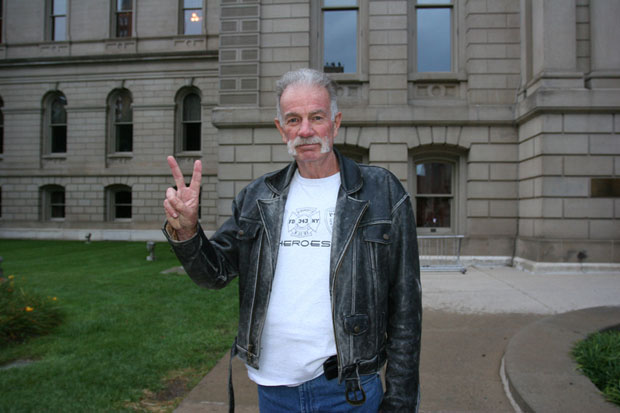

Terry Jones

(Image: Mark Brunner/Demotix)

The American pastor became known across the world when he threatened to stage a mass burning of the Koran in 2010 to mark the anniversary of 9/11 — something which in the end did not take place. In 2011 he was invited to attend a number of demonstrations with far right group England Is Ours. However, he was banned by the Home Office, which cited “numerous comments made by Pastor Jones” and “evidence of his unacceptable behaviour”. Jones responded saying: “We feel this is against our human rights to travel and freedom of speech.”

Dyab Abou Jahjah

(Image: Wikimedia Commons)

The then Belgium-based founder of the Arab European League spoke at a meeting of the Stop The War Coalition in March 2009. He left the country with the intention of coming back after a few days, only to discover that he was barred from entering Britain. His organisation had previously published “a series of antisemitic and Holocaust revisionist cartoons in response to the Danish Muhammad cartoons controversy.” Around the time of his visit, the president of the Board of Deputies, Henry Grunwald QC, wrote to then-Home Secretary Jacqui Smith “raising concerns about Jahjah”. In a post on his website, he said he believed his ban was “mainly to do with the lobbying of the Zionists”.

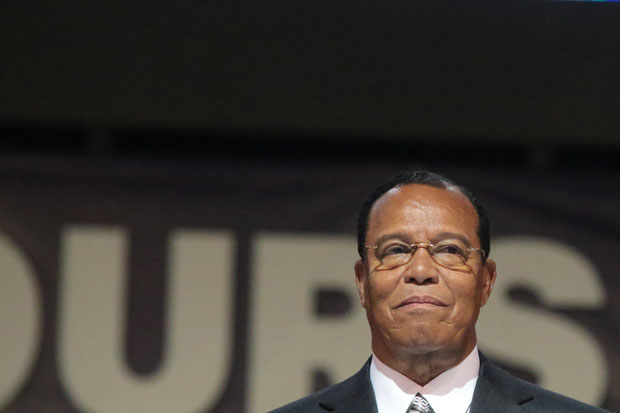

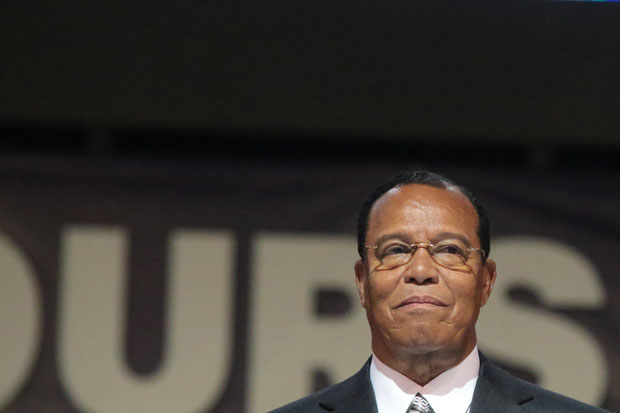

Louis Farrakhan

(Image: Thabo Jaiyesimi/Demotix)

The American Nation of Islam leader has been banned from entering the UK since 1986, due to racist and antisemitic remarks like calling Jews “bloodsuckers” and Judaism a “gutter religion”. The ban was briefly overturned in 2001 by a High Court ruling, but the government won out in the Appeals Court the following year.

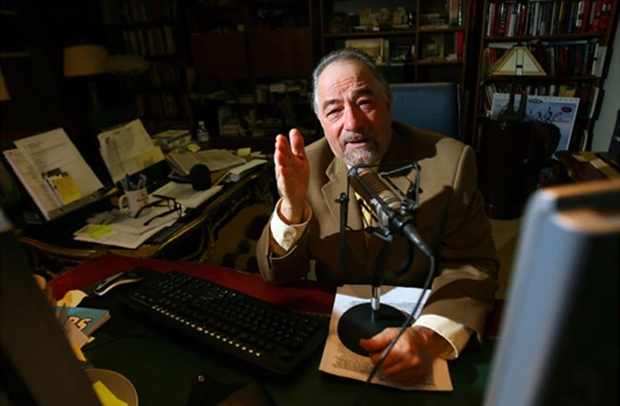

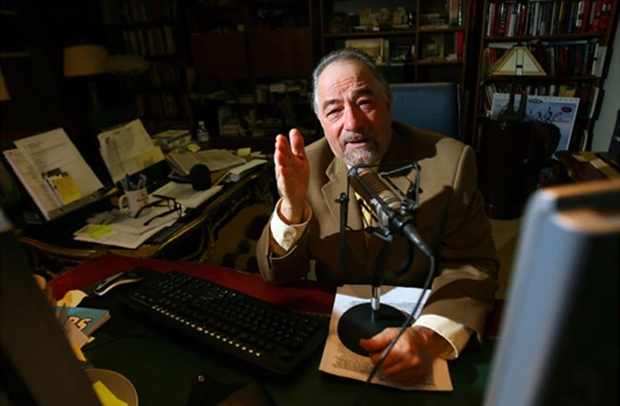

Michael Savage

(Image: Clifford Dombrowski/YouTube)

In 2009, then Home Secretary Jacqui Smith announced a 16-person banned-list, made public in a bid to explain the authorities reasoning for barring people from entering the country. On the list was shock-jock Savage — a popular American talk radio host, who has outraged listeners with comments like “Latinos ‘breed like rabbits'” and “Muslims ‘need deporting'”. He was banned for being “likely to cause inter-community tension or even violence”. Savage reacted with disbelief, claiming he would sue Smith. The ban was reaffirmed in 2011.

This article was originally posted on 5 February 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

5 Feb 2014 | Brazil, News and features, Politics and Society

In Curitiba, about 300 protesters took to the streets of the central city asking for more health and safety improvements in the country and against the hosting of the World Cup 2014 in Brazil. Photo: João Frigério / Demotix

In the wake of mass protests sparked by rising transport fares in 2013, Brazil has embraced measures aimed at containing protests. One of the most controversial bans the use of masks during demonstrations.

Approved by the governor of Rio de Janeiro, Sergio Cabral, Act 6.528 stipulates that it is “especially forbidden” to wear masks or other means to prevent identification of protesters. The criminalization of masks was also adopted by the state of Pernambuco and cities across the country without legislative consideration. Act 6.528 also contains a provision that requires telephone companies and internet service providers to respond within 24 hours to police requests for information about masked demonstrators that have been arrested.

The Rio de Janeiro law not only prohibits masks: hoods, scarves or anything that hides the face of demonstrators is likely to draw the attention of security services. Protesters who refuse to remove their mask are taken to a police station to be photographed and fingerprinted for identification.

While violence was limited to small groups during the mass protests that target social inequality, official corruption and the staggering cost of the 2014 Brazil World Cup venues, the Brazilian media has routinely showed photos of masked participants and labelled them as “vandals”, “rioters” and “anarchists”.

Authorities say the mask ban is justified and necessary to protect public and private property from “criminals” and in the name of “public safety”. But some Brazilian lawyers say the ban is a fundamental violation of civil rights and is a dangerous precedent for the country’s democracy.

Specifically, legal specialists say, the prohibition violates Article 5 of Brazil’s federal constitution. In September, the National Human Rights Commission of the Ordem dos Advogados do Brazil challenged the mask ban in court. Another legal challenge has been filed in Rio de Janeiro state as the law “prevents the citizen’s right to free expression”. So far, neither challenge has had any effect.

Human rights organizations claim that the prohibition is an extreme violation of freedom of expression and charge the government with authoritarian motives. Amnesty International has called on the government to respect the right to protest, and halt the arbitrary arrests and criminalization of protester, since the actions are a violation of Brazil’s constitution. Further, Amnesty says, the ban endangers the fundamental principles of a democratic state and are “typical of authoritarian regimes”.

In late January, demonstrations against the World Cup took place in 14 cities – led by hundreds of masked protesters. In Sao Paulo alone, more than a 100 people were arrested. One unmasked protester, Fabrizio Proteus, was shot twice and interrogated by police officers while he was still in intensive care. Activists claim the interrogation and the information he provided was illegal.

For her part, Brazil’s president, Dilma Rousseff, who is worried about elections, is backing an extensive advertising campaign to defend the World Cup. Public spending on the event has topped 8 billion Reais or £2.032 billion. Critics of the government spending have formed a movement under the banner of “Nao Vai Ter Copa”, “No World Cup”, to cause agitation against the games. The president’s advisors say new mass protests may have a negative impact on her re-election plans. In 2013, Rousseff’s popularity ratings fell over 20 per cent during the protests.

In the meantime, the Federal Police and the Agência Brasileira de Inteligência (Brazilian Intelligence Agency – Abin) are scanning the internet, especially on social networks, in search of “agitators” and suspects.

Everything indicates that repression has just begun.

This article was originally published on 5 February 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

5 Feb 2014 | About Index, Campaigns, Press Releases

After two years at the helm of Index on Censorship, Chief Executive Kirsty Hughes will be leaving the leading international freedom of expression organisation in mid-April to pursue new projects and writing in the international and European politics arena.

Hughes joined Index in April 2012 taking its international editorial and advocacy strategy to new audiences and leading Index in its work on international digital freedom, including Index’s opposition to mass surveillance as revealed by the Snowden revelations, reinforcing its work in authoritarian and transition regimes around the world, and introducing a new focus on the question of access to freedom of expression. Hughes has been a key commentator and evangelist for Index, raising the organisation’s profile in the United Kingdom, India, Brazil, the EU and the United States.

Index on Censorship is currently seeking a leading free speech defender as our new CEO. Full details on the role can be found here.