27 Aug 2014 | Asia and Pacific, India, News and features

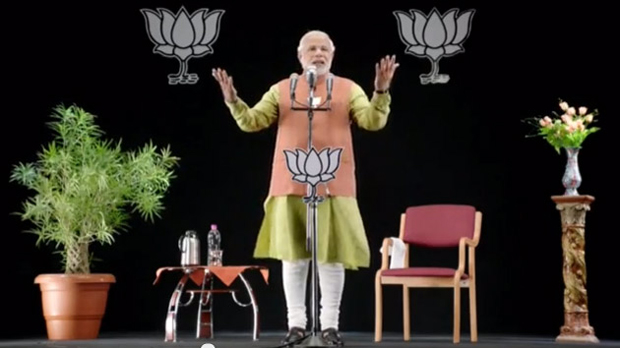

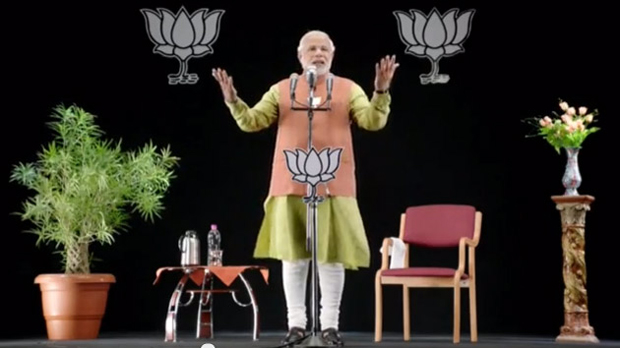

While campaigning to become prime minister, Narendra Modi addressed voters through 3D technology on several occasions (Photo: Narendramodiofficial/Flickr/Creative Commons)

Indians don’t usually take much notice of the prime minister’ speech on independence day in the middle of August. This year was different. This year there was so much discussion on social media that it became a trending topic.

In contrast to the way other prime ministers have handled this moment, new Prime Minister Narendra Modi of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), wowed a large section of Indian society not just with what he said, but the way he said it. People are gushing over the fact that he spoke without notes, and did not use the usual bulletproof glass. Others are impressed with the content; he touched upon topics as diverse as rape, sanitation, manufacturing, and nation building, using easily accessible language. Modi is also using social media to get his views across direct to the public, and bypassing the mainstream media.

This straight-talking style only adds to Modi’s brand, but he is also attracting criticism from the mainstream media for not being willing to answer hard questions. His chosen methods of communicating with the public have one common thread: he prefers to address the public directly, plainly, without going through the mainstream media or any reliance on further explanation by them. His social media accounts on Facebook and Twitter have completely changed the way information comes out of the prime minister’s office (PMO). Modi’s tweets, both from his personal and his prime ministerial account, keep citizens updated on his various trips (“PM will travel to Jharkhand tomorrow. Here are the details of his visit”). He also updates on his musings (“I am deeply saddened to know about Yogacharya BKS Iyengar’s demise & offer my condolences to his followers all over the world”) and highlights from speeches made across the country (“when the road network increases the avenues of development increase too”), as well as photographs and videos. Citizens are getting a front row seat at his speeches and thoughts. But not everybody is happy about this — especially not the private mainstream media.

Unlike the previous government, Modi is yet to appoint a press advisor. That person, normally chosen from senior journalists in New Delhi, advises the prime minister on media policy. There isn’t a point person from the PMO for the mainstream media — or the MSM, as it is called — to discuss stories and scoops. He only takes journalists from the public broadcasting arms — radio and TV — on his foreign trips, in contrast to his predecessor, who brought along more than 30 journalists from the public and private channels. In fact, Modi has reportedly instructed his MPs to refrain from speaking to journalists. Indian mainstream media is filled with complaints that Modi is denying journalists the opportunity to engage with complex subjects like governance beyond official statements and limited briefings. Meanwhile, some other publications have scoffed that the mainstream media is only complaining because it will be forced to analyse the news and work towards coherent reporting instead of relying of well honed cosy relationships with people in power.

This apparent rift between the PMO and the private mainstream media has to be viewed through a variety of prisms for it to make any sense. The first is the very volatile relationship between Modi and the MSM which harks back to his time as chief minister of Gujarat, when a brutal communal riot took place. The second is the state of the mainstream media itself, continuously called out for unethical practices by the likes of the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India.

The relationship between Modi and the mainstream media is complex. No court has indicted Modi for any criminal culpability in the Gujarat riots of 2002, but many in the media have held him morally responsibly for the mass killings that carried on over three days, and let their feelings colour reports on him. But right before Modi’s historic sweep of the Indian general elections, this section of the press seemed to have begrudgingly warmed to the man they had long vilified.

One of India’s most respected journals, Economic and Political Weekly, published the article Mainstreaming Modi, deconstructing this new wave of coverage. It argued that the reasons for this change “range from how even the United Kingdom and the European Union have ‘normalised’ relations with him [Modi], that he has been elected thrice in a row to the chief ministership of Gujarat, which surely speaks of his abilities as an ‘efficient’ and ‘able’ administrator, that Gujarat has become corporate India’s favourite investment destination, and most importantly, that he is the guy who can take ‘decisions’ and not keep the nation waiting for action.”

During this year’s election campaign, Modi’s use of the media was innovative. Stump speeches were tailor made for the towns he was campaigning in. Modi’s 3D holograms, deployed in small towns while gave a speech elsewhere, were a spectacle not seen before in India. Though Modi had been speaking to Hindi and other Indian language media, he delayed giving interviews to the English language “elite” media, watched by a small but influential section of the population. He finally consented to doing a one-on-one interview with Arnab Goswami of Times Now, known as one of India’s loudest and most aggressive anchors. People readied themselves for the ultimate combative hour on television, but Modi’s no-nonsense answers, it seemed, won over both the anchor and the audience — especially as they were in sharp contrast to the vague statements put across by Modi’s challenger, Indian National Congress Party candidate Rahul Gandhi.

After the election win, India’s mainstream media has been forced to reassess what it wants from the prime minister. Is it information or is it access? The mainstream media undoubtedly has had a very complicated and close history with the political class. A Congress-led government has been ruling New Delhi for a decade, building up close relationships with senior editors and journalists. Some of these relationships were exposed through leaked conversations between members of the press and corporate lobbyists in a scandal now known as the Radia Tapes. They revealed, among other things, how journalists used their connections to politicians to pass on messages from lobbyists.

In fact, the indictment of improper behaviour by the media is a fairly regular occurrence in India. Just this month, the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India released their latest report, which recommends that corporate and political influence over the media can be limited by restricting their direct ownership in the sector. For this reason, the credibility and true affiliation of the media is always under the scanner.

But Modi and his team also need to respond to questions about why they will not deal with some parts of the media. How do they view the role of a combative media? Is only the public broadcaster, which reports the story as the government wants, to be allowed access? Are critical questions being avoided?

Perhaps, the last word can go to Scroll.in, one of India’s newest online magazines: “[T]he rat race for the ego scoop undermines the most important scoop, the thought scoop. We often don’t look at the big picture, don’t take the long view, don’t see the obvious, forget the past, don’t study the boring reports, substitute access journalism for ground reporting, believe the official word. Narendra Modi might just be doing us a favour by keeping us away.”

This article was posted on August 27, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

22 Aug 2014 | Events

YOU CAN NOW WATCH THIS CONVERSATION AND READ A FULL ENGLISH TRANSCRIPT HERE.

Index on Censorship is delighted to announce the second in a series of online conversations about artistic freedom of expression in Wales.

This conversation forms part of our ArtFreedomWales programme looking at how artistic freedom is regarded, debated and promoted across the arts sector in Wales – in the press, by the public, by funders and policy makers.

Artists working in Welsh – opportunities and obstacles to expression?

Online conversation with:

- Mari Emlyn – Chief Executive Officer Galeri

- Arwel Gruffydd – Artistic Director Theatr Genedlaethol Cymru

- Bethan Jones Parry – Broadcaster, Journalist and Writer

- Bethan Marlow – Playwright and Storyteller

- Iwan Williams – Independent Creative Producer and Development Officer for Creadigol Mentrau Iaith Cymru

Where: Catch up with the Google Hangout here

Please note: this conversation will be in Welsh with an English summary at the end.

This is the second of four events on artistic freedom of expression in Wales that we are live-streaming, leading up to a national symposium at Chapter Arts Centre in Cardiff (27th November). You will be able to email and tweet questions to the panels during the discussion.

What are the issues in Wales? What are the opportunities? What are the obstacles? What has the right to freedom of expression got to do with Wales’ major cultural debates and policies: bi-lingualism, engaging young people and ethnically diverse voices, tackling poverty, maximising on new cultural infrastructure, having an international voice?

We want to hear from everyone producing and participating in the arts in Wales who has something to say about freedom of expression.

The first online conversation which took place in July featured Tim Price (playwright), Kathryn Gray (poet and writer), Lisa Jen (musician/actor/writer) and Leah Crossley (artist). See it here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pNv1J0_jRQY

Arts Council of Wales supports this programme

22 Aug 2014 | About Index, Events, United Kingdom

Mae Index on Censorship yn falch o gyhoeddi yr ail ddigwyddiad mewn cyfres o drafodaethau ar-lein am ryddid mynegiant artistig yng Nghymru.

Mae Index on Censorship yn falch o gyhoeddi yr ail ddigwyddiad mewn cyfres o drafodaethau ar-lein am ryddid mynegiant artistig yng Nghymru.

Mae’r trafodaethau yn ran o raglen sydd yn edrych ar sut y mae rhyddid artistig yn cael ei ystyried, ei gefnogi, ei drafod a’i hyrwyddo ar draws y sector gelfyddydol, yn y cyfryngau, gan y cyhoedd, gan ariannwyr ac gan wnaethurwyr polisi yn y DU.

Artistiaid yn gweithio yn y Gymraeg – cyfleon a rhwysterau i fynegiant.

Trafodaeth ar-lein gyda:

- Mari Emlyn – Cyfarwyddwraig Artistig Galeri.

- Arwel Gruffydd – Cyfarwyddwr Artistig Theatr Genedlaethol Cymru.

- Bethan JonesParry – Darlledwraig, Newyddiadurwraig ac Ysgrifennwraig.

- Bethan Marlow – Dramodwraig a Storïwraig.

- Iwan Williams – Cynhyrchydd Creadigol Annibynol a Swyddog Datblygu Creadigol Mentrau Iaith Cymru.

Pan: Awst 26ain 11.30yb

Ble: Google Hangout yma

Sylwer bydd y drafodaeth yn Gymraeg gyda chrynodeb Saesneg ar y diwedd.

Dyma’r ail o bedwar digwyddiad rydym yn eu ffrydio’n fyw yn ystod yr hafa fydd yn arwain at symposiwm am ryddid mynegiant artistig yng Nghymru yng Nghanolfan Celfyddydau Chapter, Caerdydd (27 Tachwedd). Bydd modd i chi anfon cwestiynnau drwy system holi ac ateb Google Hangout neu drydar y panelwyr yn ystod y drafodaeth.

Beth yw’r materion yng Nghymru? Beth yw’r cyfleon? Beth yw’r rhwystrau? Beth sydd gan ryddid mynegiant artistig i wneud gyda phrif drafodaethau celfyddydol a pholisiau – dwyieithrwydd, denu pobl ifanc a lleisiau ethnig amrywiol, ymdopi â thlodi, manteisio ar rwydweithiau diwylliannol newydd, meddu ar lais rhyngwladol?

Hoffem glywed gan bawb sydd yn cynhyrchu ac yn ymwneud â’r celfyddydau yng Nghymru ac sydd â rhywbeth i’w rannu am ryddid mynegiant. Bydd y trafodaethau hyn yn bwydo agenda y symposiwm yng Nghaerdydd a bydd pob un yn rhoi ffocws ar thema gwahanol y byddwn wedi ei ganfod yn ein hymchwil cychwynnol.

Cafodd y drafodaeth ar-lein gyntaf ei gynal ym mis Gorffennaf. Yn cymeryd rhan roedd y dramodydd Tim Price, y gantores, actores a’r ddramodwraig Lisa Jên, y bardd a’r ysgrifennwraig Kathryn Gray a’r artist gweledol Leah Crossley. Mae modd ei wylio yma https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pNv1J0_jRQY

Arts Council of Wales supports this programme

22 Aug 2014 | Egypt, Middle East and North Africa, News and features

Street art from Mohamed Mahmoud Street, Cairo. (Photo: Melody Patry/Index on Censorship)

Before the January 2011 uprising, street art was little known in Egypt. Then came the revolution and with it, an outburst of creativity.

With the fall of the authoritarian regime of Hosni Mubarak, Egyptian artists who had routinely faced censorship restrictions under his autocratic rule, felt a strong urge to break out of the confines of their studios and reclaim public spaces. Young artists in particular, decided they needed bigger canvases for the grand ideas they wanted to convey through their paintings. To celebrate their newfound liberation, many of them took their art directly to the people and onto the streets, expressing their views and opinions on public walls and on the sides of buildings.

Bonded by their shared aspirations for a better Egypt, the young graffiti artists spent long hours working together, creating vivid group murals that told the stories of the revolution in which they had actively participated. The images they produced in the months following the 2011 uprising documented the dramatic changes that were unfolding in the country, the continued unrest ensuring a steady supply of material for them to work with. The artists also spread powerful messages of “equality” and “freedom” that helped shape public opinion, attitudes and values.

“Our murals added colour to the otherwise dull streets and boosted the morale of the people. But as graffiti artists and activists, we also played the role of the ‘alternative critical media,’ telling the untold stories and spreading messages that helped the public better understand what was really happening on the ground,” said graffiti artist Salma Sami, a graduate of fine arts who has also worked as a broadcaster.

An image of Pinnochio on TV, spray-painted on a wall on Mohamed Mahmoud Street, off Tahrir Square, shortly after the fall of Mubarak, was intended to poke fun at state media — for long, a propaganda tool of the ousted Mubarak regime. According to Sami, the mural also “serves as a warning to Egyptians not to believe everything the media tells them”.

Besides being a critical voice, raising awareness and informing the public of the events unfolding in the country, Cairo’s nascent street art movement also helped keep the spirit of the January 25 revolution alive.

“As a woman, I wasn’t accustomed to working in the street and was afraid at first especially after hearing stories of sexual assault incidents in the very neighbourhood where we worked. But once I started working, I felt safe. Working in a group helped us revive the spirit of the revolution, letting go of our fears and uniting behind a common goal,” Sami said.

The street artists successfully managed to break down social barriers of class, religion and gender. They created a close-knit community among themselves but were also accessible to the public.

“Crowds would often gather to watch as we worked and then, someone would volunteer to help. Soon, we would find others joining in. The fact that a lot of our work was painted with roller brushes made it easy for anyone to participate,” Sami told Index.

(Photo: Melody Patry/Index on Censorship)

Like Sami, Bahia Shehab — an art historian and graphic designer — was also very much a part of the street art movement that emerged and developed after the 2011 revolution. Her trademark “no” stencils, spray painted on the walls of Mohamed Mahmoud Street have helped draw public attention to social problems, exhorting Egyptians to take a stand against violence, oppression, and other forms of injustice.

Shehab joined the street art movement nine months after the revolution when she saw an image of a protester’s corpse dumped in a pile of rubbish in her Facebook newsfeed. The gruesome picture, which had gone viral on social media networks, so infuriated her that she rushed to Tahrir Square to express her rage. Her stencilled message “no to military rule” marked the beginning of her “thousand times no” campaign — a series of images decrying torture, sexual violence and other issues she felt strongly about.

Carrying on the idea from her 2010 book — a compilation of “one thousand no-s” in a multitude of Arabic calligraphy styles — she added a range of fiery messages denouncing rights abuses that were committed during the country’s transitional period. ”No to violence and thuggery”, “no to stripping girls” and “no to sectarian divisions” are just a few in her long list of stencilled images.

More than three years after the uprising that toppled autocrat Hosni Mubarak, Shehab says her “old” list is “still relevant” and her concerns “still valid”. She continues to consistently add more “no” messages, saying she is “deeply disappointed” with the turn of events in her country. Among the new additions is a stencil calling for an end to the brutal security crackdown on dissent.

A nationalist fervour sweeping the country has however made it dangerous for graffiti artists to express themselves freely. Those who dare criticise government policies are often accused of being “traitors” and “terrorists” by self-proclaimed “patriots”. Today, while many of the young street artists view former army chief and current president Abdel Fattah el-Sisi as merely the new face of the old military regime, few dare depict him in their artworks. Sisi came to power following the 2013 coup that overthrew Egypt’s first democratically elected president, the Muslim Brotherhood’s Mohamed Morsi. Several established street artists have chosen to remain anonymous, signing their artworks using nicknames for the sake of their security.

“Working in the street has always been dangerous,” noted Shehab, adding that “the only difference is that the danger now comes from violent ‘patriotic’ mobs supporting the military where before it was from the police.”

But mob violence is not the only danger threatening Egypt’s street art movement. A proposed draft law banning so-called “abusive graffiti art” — if passed — may likely restrict artistic expression and may spell the end of the graffiti tradition, even before it fully emerges. Under the draft law, violators could face a prison sentence of up to four years or a fine of up to 100,000 Egyptian pounds.

The recent alleged murder of one of Shehab’s comrades — 19 year-old graffiti artist and member of the April 6 youth movement Hisham Rizk — has compounded her fears, sending shivers down many spines in Egypt’s artistic circles. Rizk’s body was found in a Cairo morgue last month, a week after his family reported his “mysterious disappearance”. A forensic report concluded that the young artist had died of “asphyxiation by drowning in the Nile River”. Sceptical fellow artists however, believe Rizk’s critical views of the government expressed in his drawings and on Facebook may have instigated a confrontation with security officials that led to his death.

(Photo: Melody Patry/Index on Censorship)

“People don’t always agree with our views and different people interpret our artworks in different ways but at least our murals provide food for thought,” noted Sami who, in early 2012, designed a controversial mural depicting a skull with a military cap, holding a flower between clenched teeth. The image was a fitting portrayal of the brutal military regime that replaced Mubarak after the revolution. The 18-month rule of the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) was marred by political turmoil and violence including forced virginity tests performed by the military on female protesters

You can still see Sami’s mural on Mohamed Mahmoud Street, along with many others that are critical of both SCAF and the Muslim Brotherhood. The latter are depicted as sheep, while military men are portrayed as butchers in some of the murals. The colourful artworks are reminiscent of a happier time of free artistic expression and hope — a phase that, some of the artists fear, may well be over.

Yet, both Sami and Shehab remain defiant, saying that neither laws nor intimidation will deter them from the journey they have started. They draw similarities between their art and the 2011 revolution, saying both are constantly shifting and come in waves. Their murals in downtown Cairo have been whitewashed several times with other artists painting over them or adding new images as new events unfold, sparking new ideas. “Sometimes, residents in the area paint over the images if they oppose our views,” said Sami.

“I no longer mind when my work disappears. When that happens, I just tell myself it’s time to design a new stencil and I head straight back to Mohamed Mahmoud Street.”

The Index on Censorship interactive documentary Shout Art Loud explores how Egyptians use graffiti and other art forms to tackle the issue of sexual harassment and violence against women. Watch it here.

This article was posted on August 22, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

Mae Index on Censorship yn falch o gyhoeddi yr ail ddigwyddiad mewn cyfres o drafodaethau ar-lein am ryddid mynegiant artistig yng Nghymru.

Mae Index on Censorship yn falch o gyhoeddi yr ail ddigwyddiad mewn cyfres o drafodaethau ar-lein am ryddid mynegiant artistig yng Nghymru.