1 Aug 2014 | Digital Freedom, India, News and features

The Global Network Initiative (GNI) and the Internet and Mobile Association of India (IAMA) have launched an interactive slide show exploring how India’s internet and technology laws are holding back economic innovation and freedom of expression.

India, which represents the third largest population of internet users in the world, is at crossroads: while the country protects free speech in its constitution, restrictive laws have undermined Indias record on freedom of expression.

Constraints on digital freedom have caused much controversy and debate in India, and some of the biggest web host companies, such as Google, Yahoo and Facebook, have faced court cases and criminal charges for failing to remove what is deemed objectionable content. The main threat to free expression online in India stems from specific laws: most notorious among them the 2000 Information Technology Act (IT Act) and its post-Mumbai attack amendments in 2008 that introduced new regulations around offence and national security.

In November 2013, Index launched a report exploring the main challenges and threats to online freedom of expression in India, including takedown, filtering and blocking policies, and the criminalisation of online speech.

This article was posted on Aug 1, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

31 Jul 2014 | Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan News

One of the few remaining independent media outlets in Azerbaijan, the 2014 Index on Censorship Guardian Journalism Award-winning newspaper Azadliq has been forced to suspend publication due to an ongoing financial crisis. This comes just a day after the government of Azerbaijan targeted prominent human rights defenders Leyla and Arif Yunus and Rasul Jafarov. Yunus and her husband have been detained for three months as prosecutors build a case around charges that include high treason. Jafarov has been banned from traveling.

The paper’s Editor-in-Chief Rahim Haciyev told Contact AZ that without an immediate payment of 20,000 manat (£15,105.39) to its printer, the latest issue would not be produced. The paper’s government-backed distributor, which according to Haciyev owes Azadliq 70,000 manat (£52,868.86), has refused. This is not the first time that Azadliq, which has reported on government corruption and cronyism, has faced a financial cliff.

Read more about Azadliq here.

Index Reports: Locking up free expression: Azerbaijan silences critical voices (Oct 2013) | Running Scared: Azerbaijan’s silenced voices (Mar 2012)

This article was posted on July 31, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

31 Jul 2014 | Ireland, News and features, Pakistan, Religion and Culture

It was, apparently, the posting of a “blasphemous image” on Facebook that led an angry mob to burn down houses with children inside them.

It’s been suggested that it was a picture of the Kaaba, Islam’s holiest site, that provoked the mob in Gujranwala in Pakistan. They rallied last Sunday at Arafat colony, home of 17 families belonging to the Ahmadi sect. As police stood by, houses were looted and torched. At the end of the night, a woman in her 50s, Bushra Bibi, and her granddaughters Hira and Kainat, an eight-month-old baby, were dead. None of them had anything to do with the blasphemous Facebook post.

Was the image even blasphemous? In some ways, it doesn’t really matter. What matters was that it was posted by an Ahmadi, whose very existence is condemned by the Pakistani penal code.

Ahmadiyya emerged in India in the late 19th century. It is a small sect based on the belief that its founder, Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, was, in fact, the Mahdi of Muslim tradition. This teaching is rejected by Orthodox Sunni Islam.

In Pakistan, this means that being a member of the Ahmadiyya sect is dangerous. The law says you cannot describe yourself as Muslim. You cannot exchange Muslim greetings. You cannot describe your call to prayer as a Muslim call to prayer. You cannot describe your place of worship as a Masjid.

Any Ahmadi who “any manner whatsoever outrages the religious feelings of Muslims” can be imprisoned for up to three years.

Ahmadis suffer disproportionately from Pakistan’s blasphemy laws, but they are not the only ones who suffer. Accusations of blasphemy are frequently levelled at members of other minorities and at mainstream Muslims too. Often, this is done out of sheer spite. Often it is done to settle scores.

As the New Statesman’s Samira Shackle has pointed out, amid the chaos and fear generated by the law, it’s often difficult to find out what people are actually supposed to have done, as media hesitate to repeat the alleged blasphemy lest they themselves be accused of the crime.

The fevered atmosphere created by the laws mean that to oppose them can be fatal. In Janury 2011, Punjab governor Salmaan Taseer was killed by his own bodyguard after he pledged to support a Christian woman, Aasia Bibi, who had been accused of the crime. Taseer’s assassin claimed that the governor had been an “apostate”. He was widely praised by the religious establishment. Three months later, Minority Affairs Minister Shahbaz Bhatti was killed, apparently because of his belief that the blasphemy law should be changed.

Meanwhile, an amendment proposed by Taseer’s colleague Sherry Rehman, which would have abolished the death penalty for blasphemy, was dropped. Rehman was posted to diplomatic service in the United States later that year, amid allegations that she herself had committed some kind of blasphemy.

The number of blasphemy cases is steadily rising, and Human Rights Watch recently claimed that 18 people are on death row after being found guilty of defaming the prophet Muhammad, though no one has as yet been executed.

The laws may seem archaic, but they are in fact utterly modern. While some of South Asia’s laws on religious offence date back to the Raj, the laws relating to the Ahmadi, and the law making insulting Muhammad a capital offence only emerged in the 1980s, as part of General Zia’s attempts to shore up his religious credentials.

The sad fact is this Pakistan’s new enthusiasm for blasphemy laws is not an international aberration. Nor is this a trend confined to confessional Islamic states.

Ireland’s 2009 Defamation Act introduced a 25,000 Euro fine for the publication of “blasphemous matter”. According to the Act , “a person publishes or utters blasphemous matter if—

(a) he or she publishes or utters matter that is grossly abusive or insulting in relation to matters held sacred by any religion, thereby causing outrage among a substantial number of the adherents of that religion, and

(b) he or she intends, by the publication or utterance of the matter concerned, to cause such outrage.”

Note how similar the wording is to the Pakistani law forbidding Ahmadis from offending Muslims. The Pakistani government repaid the compliment when, along with other members of the Organisation of Islamic Conference, it attempted to force the UN to recognise “religious defamation” as a crime, lifting text from the Irish act. Pakistan claimed, grotesquely, that criminalising blasphemy was about preventing discrimination. Cast your eyes back once again to how its blasphemy provisions treat Ahmadis.

Across Europe, more and more blasphemy cases are emerging. In January of this year, a Greek man was sentenced to 10 months for setting up a Facebook page mocking an Orthodox cleric. In 2012, Polish singer Doda was fined for suggesting that the Bible read like it was written by someone drunk and “smoking some herbs”. The trial of Pussy Riot in Russia was heavy with talk of sacrilege.

We tend to believe that the world is moving inexorably toward a secular settlement. The unintended upshot of this prevalent belief is that organised religions, even in countries like Pakistan, get to portray themselves as weak people who need to be protected from extinction, even as they wield power of life and death over people.

Religious persecution is real, and should be fought. Freedom of belief is a basic right. But blasphemy laws protect only power, and never people.

This article was posted on July 31, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

31 Jul 2014 | Mali, News and features, Religion and Culture

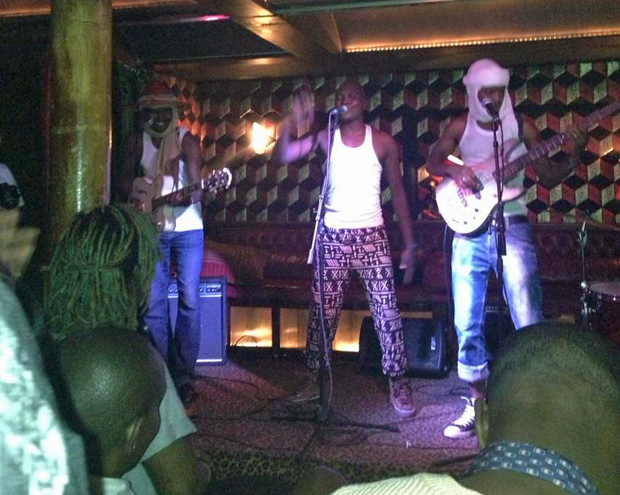

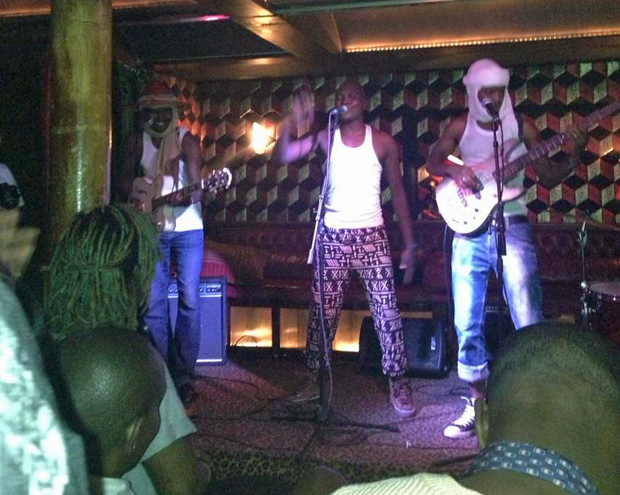

Songhoy Blues, performing in London, asked the audience to imagine music being banned in the UK.

Aliou Touré, lead vocalist of the Malian band Songhoy Blues, introduced their concert in London by talking about the challenges musicians face in Mali, where music was banned by a local armed Islamist group in the north of the country in 2012.

“It is liberating to be able to perform tonight because in my country, I do not have the same freedom of expression,” Touré added before the kick off.

As the concert rolled on, one could easily forget that Songhoy Blues — who are touring in the UK ahead of their album launch later in the year — were deprived from playing music at home.

In September 2013, documentary filmmaker Johanna Schwartz wrote for Index on Censorship magazine on the censorship and persecution that musicians in Mali have faced since the ban on music: “There is a fear that freedoms may not be so easily restored,” wrote Schwartz. Today, although the ban has been theoretically lifted, the fear remains. “Because of the violence, it is still impossible for me to play music in my hometown,” said Touré, who is from the northern city Gao.

Like thousands of refugees, Touré left for Bamako amid escalating violence.

In the capital city, Touré and other musician friends — Garba, Oumar and Nathanael — from the north decided to form a band. The very creation of their band is an act of hope and resistance: “Somehow, the ban on music played in our favour because it’s only after we left the north that we came together and formed Songhoy Blues,” explained Touré.

The band is now based in Bamako, where the members long for the weekend to perform in local bars. But as music was being driven out of the country — even those with musical ringtones on their mobile phones faced crackdowns — many musicians fled Mali. They Will Have to Kill Us First, Schwartz’s feature-length documentary, follows the story of Mali’s musical superstars as they fight for their right to sing.

At this time, They Will Have to Kill Us First is in the final stages of shooting, and it is still uncertain if Songhoy Blues and the other Malian musicians in exile will feel safe enough to return to home.

This article was posted on July 30, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org