12 Jun 2014 | Brazil, Digital Freedom, Digital Freedom Statements, News

This is the first in a series of articles based on the Index report: Brazil: A new global internet referee?

When it comes to the free expression, Brazil is a conundrum. On the one hand it is among the top requesters to Google and other internet firms for content takedowns. On the other hand, Brazil has passed a progressive law – Marco Civil — putting it on a footing to be one of the world leaders on internet freedom.

President Dilma Rouseff signed the Civil Rights Framework for the internet on 23 April 2014, two years after the bill was first introduced in Congress. The movement that resulted in law n° 12.965, 23 April 2014 – referred to as Marco Civil da Internet or simply Marco Civil – began in 2007. Marco Civil was drafted with three key issues in mind: Net neutrality, freedom of expression and user privacy.[1] The bill was particularly welcomed by Brazilian civil society at a time when the country is still facing many restrictions to free speech online and off.

While the enacting of Marco Civil represents a step forward for freedom of expression in Brazil, there are offline issues that the country needs to address.

Brazil’s Federal Constitution guarantees Brazilian citizens broad access to information from multiple sources. Chapter 5 of the Constitution protects freedom of expression and freedom for the press, and forbids “any and all censorship of a political, ideological and artistic nature”. However, the country still faces traditional restrictions to freedom of expression – where journalists have been threatened and even killed. In the last decade, more Brazilian citizens have become highly active internet and mobile users, yet – in common with other countries – that has often led to a clash between those welcoming and using the new freedoms and those trying to step in to constrain free speech online. Bloggers and web journalists have been threatened with litigation, and attacked or even murdered for expressing their views on the internet.

With 11 journalists killed in 2012, five in 2013, and two since the start of 2014, Brazil is one of the deadliest countries for media personnel and ranks 111 out of 180 in the 2014 World Press Freedom Index. Violence against media professionals is a serious threat to freedom of expression that worsened during the large-scale protests that erupted in São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro and other Brazilian cities in June 2013. The protests were triggered by public transport fare hikes and fuelled by discontent with massive spending on the 2014 Football World Cup and the 2016 Olympics. News providers covering the protests were among those hit by a major police crackdown. The protests also raised questions about the highly concentrated media market after the policing intensified following an editorial published in the national newspaper Folha de São Paulo that called for more “force” against protesters. Online journalists, bloggers and citizens used social platforms and internet technologies as an alternative form of journalism in response to large media outlets’ depiction of the protests. The collective Mídia NINJA, for example, attracted the attention of thousands of people during the protests for its “no-cuts, no censorship” approach. NINJA, which stands for “Independent Narratives, Journalism and Action” in Portuguese, were broadcasting live from the streets and they were the first to break news on police infiltrators and wrongful arrests. However, deprived of the resources of the mainstream media, some members of the collective were targeted by both protesters and the police.

| Case Study: Mídia NINJA

Using digital technologies to offer another media narrative: opportunities and risks

Media ownership in Brazil is highly concentrated, with 10 major companies dominating the national media. In many states, local businessmen and politicians also hold TV and radio licenses, which interferes with media plurality and independence. The emergence of the internet and access to the web via mobile phones has facilitated new forms of information sharing and citizen journalism. In the wake of the protests that shook the country in June 2013 onwards, Mídia NINJA, a journalists’ collective using social networks as a platform, grew in popularity and influence as it provides a channel for popular discontent with politics – and the media.

NINJA mainly use cell phones and other 4G devices to produce its broadcasts. The traction and interest NINJA generated became obvious during the protests, when their livecasting of the events reached more than 100,000 viewers. In the meantime, their Facebook page, created in March 2013, has drawn more than 260,000 likes. Bruno Torturra, founder of Midia NINJA, told Index on Censorship: “Because of our agility, our national presence and the way we challenge the official media narrative, we were catapulted to fame in days. Hundreds of people joined, we were able to cover more than 100 cities and produce tons of information.”

But the growing influence of these new independent and online journalists comes with risks. Many in the group feel they have been singled out by police for contradicting the official version of events. “We have already taken rubber bullets, tear gas, stones, fragments of grenades. We’ve been sprayed with fire hoses and pepper spray and been verbally threatened. In the whole country, eight reporters have been detained and, in some cases, suffered physical aggression,” said Filipe Peçanha, another NINJA collaborator who was detained while filming a protest. |

Mídia NINJA were by no means the only group to be targeted during the protests, which refocused attention on the brutal methods used by the state military police. Free speech and human rights organisations have denounced excessive use of force against protesters and received complaints about some police officers monitoring social media, asking for Facebook passwords, and then detaining or arresting people for Facebook posts.

Many journalists were injured and apprehended while covering protests. Pedro Roberto Ribeiro Nogueira, a reporter for the website Portal Aprendiz, was among the journalists beaten up and detained by the military police while covering the protests in June 2013. He was first accused of “resistance” and “obstructing” police work. Once at the police station, charges were changed to

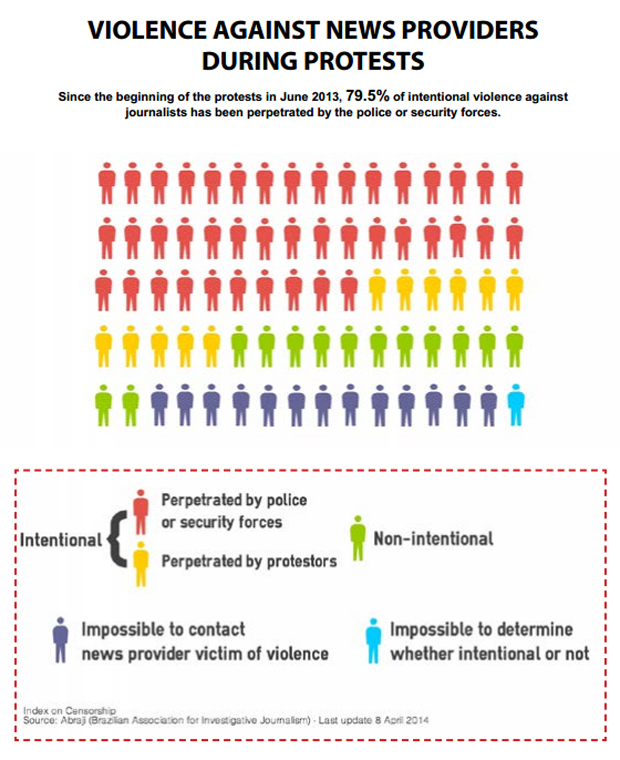

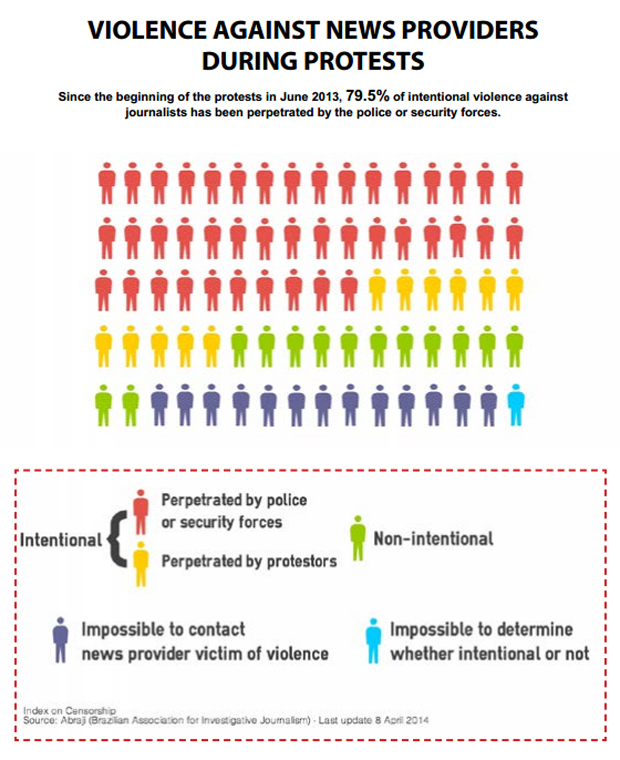

“vandalism” and “formation of a gang”. Nogueira stayed in jail for three days, until a video showing the police beating him went viral on the web. But even after his release, harassment continued.[2] Nogueira was under house arrest from 8pm to 6am every day for two months – with interdiction to leave São Paulo on weekends. As of writing, Nogueira, whom Index interviewed for this report, is still being prosecuted for “vandalism” and “formation of a gang”. The detention and harassment of reporters trying to do their jobs – whether they work for a large media outlet or not – is of great concern. As of April 2014, in the course of the protests, 166 journalists were the victims of acts of violence, of which more than two thirds were blamed on the police.

According to Reporters Without Borders, violence against news providers also results from the phenomenon of “colonels”: regional politicians who are also businessmen and media owners. This phenomenon constitutes a major obstacle to media pluralism and independence, “turning journalists into the tools of local barons and exposing them to often deadly score-setting”. In addition, organised crimes’ hold on certain regions makes covering subjects such as corruption, drugs or illegal trafficking in raw material very risky. All cases of killings and other forms of violence against media professionals, bloggers, human rights defenders and protesters are serious violations to the rights to freedom of expression and information and should be effectively investigated. Those responsible for such attacks should be held accountable.

Media professionals and citizen journalists also face the prospect of expensive legal proceedings, which undermine the right to freedom of expression and assembly in the country. The internet, including both small news sites and blogs and web giants such as Google, has been particularly hard-hit by judicial censorship. The number of court decisions either ordering content removal or sentencing bloggers and journalists for content published online has escalated. In particular, free speech organisations and associations of journalists have denounced the use of defamation and privacy laws as intimidation and silencing tools, calling some legal decisions “scandalous and anti-constitutional”.[4] With broadly worded defamation laws and in the absence of a specific legislation to regulate online content and protect internet rights, protection of privacy and personal data online have also become a cause for concern.

Rising trend of takedown requests and censorship via the courts

In 2012, Brazil was top of the list of takedown requests[5] worldwide, ahead of the United States and Germany. Brazil has undergone an increase in content takedown requested by government agencies as well as by the judiciary. The breakdown of the Google transparency report – a bi-annual report covering requests received from copyright owners and governments to remove information from Google services – shows that defamation is the leading reason and accounts for 44% of all removal requests. Excerpts of the latest reporting period also show that in many cases, removal orders focus on blog posts criticising public officials. For example, between January and June 2013, Google received a court order to remove 107 blog posts and search results for linking to information that criticised a local government official for allegedly corrupt hiring practices.[6] Court orders went as far as banning writing posts on Facebook about specific issues or preventing people from logging into any social media (see case studies in the sidebar on page 10). Since there was no specific law governing online content, most of the controversial decisions justified the use of censorship under the country’s existing defamation and privacy laws.

In 2009, the Brazilian Supreme Federal Tribunal decided to strike down the infamous 1967 Press Law, which imposed harsh penalties for libel and slander. The 1967 Press Law, which had been adopted under the military dictatorship that ruled Brazil between 1961 and 1985, had been used to systematically harass critical journalists. While the elimination of this repressive law was welcome, many Brazilian journalists and citizens can still be jailed for up to two years under criminal defamation laws that remain in the penal code.

Defamation is a crime, which is prosecuted as “defamation” (three months to a year in prison, plus fine), “slander” (six months to two years in prison, plus fine) and/or “injury offending the dignity of another person” (one to six months in prison, or fine), with aggravating penalties when the crime is committed against the president, or against the head of a foreign government, against a public official in the performance of his official duties, or against a person who is disabled or over 60 years old.

The law defines alleged violations in broad terms – “offending the dignity of another person” – that offer room for wide interpretation and exaggeration. The provision on public officials, for example, means that reporters are sometimes prohibited from discussing investigations into political figures. They face libel charges even in obvious cases of public interest, such as investigations on corruption.

Furthermore, the country’s election law is restrictive and limits reporting on political issues during an electoral period. The law specifically protects political candidates from content that would “offend their dignity or decorum”.

Both the election and defamation laws have been used to limit or shut down the dissemination of information about public figures – both in the traditional press and online.

Free expression organisation Article 19 notes that in cases of defamation involving politicians, local courts often rule in favour of the plaintiff. This is also true when those who press charges for defamation are powerful businessmen or companies, implying that in some cases, judges and politicians/businessmen are closely linked. This phenomenon has come to be known as “judicial censorship”, which refers to the practice of politicians, business people, and celebrities using defamation and privacy laws to silence the media. In May 2013, a journalist from the Brazilian state of Amapá, Alcinea Cavalcante Costa, was ordered to pay a R$2 million fine (approx. USD 1 million) to Brazilian’s Senate President José Sarney, after someone posted a comment criticising him under an article she wrote on her personal blog in 2006. In this case, Costa was not the author of the comment for which she was condemned, but her blog had hosted it. The fact that she was so heavily fined stirred up controversy over the relations between the judiciary and Brazilian political figures, as Costa’s prosecution appeared as an attempt to shut down political criticism.

Likewise in January 2013, a judge in the northern state of Pará ruled that journalist Lúcio Flavio Pinto had to pay local businessman Romulo Maiorana Júnior and his company Delta Publicidade R$410,000 (approx. USD 205,000). The charges stemmed from a 2005 story in which Pinto alleged that Maiorana’s media group, Organizações Romulo Maiorana, had used its influence to pressure companies and politicians into giving them advertising. Maiorana said Pinto had damaged the Maiorana family’s honour and reputation.[7]

In the past five years, civil society and some internet companies have started to challenge judicial censorship and push back against takedown orders. For example, Article 19 has published a guidebook aimed at journalists and bloggers sued for defamation. At Google, the compliance rate – requests where some or all items are removed – dropped from 82% in 2009 to 21% in 2012. But challenging court orders has its limits. In September 2012, Google’s top executive in Brazil, Fabio Coelho, was temporarily detained by order of a judge from the state of Mato Grosso do Sul for not complying with a court order and “disobedience to the Electoral Code”. The judge demanded the removal of YouTube videos considered offensive against Alcides Bernal, a mayoral candidate in the state capital Campo Grande. Google challenged the court order and refused to take the video down. Since the video was not promptly deleted, Coelho was held responsible. He was questioned by federal police and released shortly after. He later expressed his concern about the episode, saying it had “intimidating effects” on freedom of expression.

Although the government does not employ any technical methods to filter online content, the escalation in government takedown requests and court-ordered censorship highlights a worrying trend to censor political criticism and dismiss free speech arguments. It seems that unlike journalists working for well-established newspapers, bloggers and independent journalists are far more likely to be censored by the courts. While Marco Civil would provide a protection for internet intermediaries by limiting notice-and-takedown procedures, judicial censorship remains a threat to Brazilian internet users.

| Controversial rulings about social media, internet content and free speech (non-exhaustive list)

In February 2013, a judge from the Brazilian state of São Paulo barred Ricardo Fraga de Oliveira, founder of the movement “The Other Side of the Wall – Collective Intervention”, from a construction site or even posting on Facebook about it. Oliveira was protesting against a construction project in his neighbourhood. He complained about possible irregularities on the site. Oliveira created a Facebook page and launched an online petition that gathered 5,000 signatures. The construction company, Mofarrej, filed a lawsuit against Oliveira, claiming his protests were slanderous and offensive against a private initiative. They also said he harassed and discouraged potential apartment buyers. The company demanded his Facebook fanpage be suspended and asked for a restraining order banning the engineer from an area of one kilometre around the construction site.

The judge banned Oliveira from visiting the construction area and ordered the shutdown of his Facebook fanpage. After his lawyer appealed the ruling, the judge maintained the restraining order, but determined that only the mentions about the construction works or Mofarrej should be removed from Facebook, or face a R$10,000 (approx. USD 4,500) fine for each violation. Oliveira ultimately decided to suspend the fanpage, since most of its posts criticised the building or the construction firm.

In April 2013, a judge from the city of Limeira, São Paulo state, banned lawyer Cássius Haddad from logging into any social media platform. Haddad was criminally cited by the state’s Public Ministry for posting attacks against prosecutor Luiz Bevilacqua on the internet. The judge ordered Facebook and Twitter to inform the court if Haddad logged into his accounts. The providers were also asked to send the court monthly reports of all attempts made by the lawyer to access their services.

In July 2013, José Cristian Góes, a reporter from the Brazilian state of Sergipe, was sentenced to seven months and one week in jail under defamation law for writing and posting a fictional short story on local political cronyism on his blog in May 2012. The short story was told from a first person point of view and did not mention location, dates or actual names.

In December 2013, a judge condemned two women for having “liked and shared” a post on Facebook. The case in question involved a Facebook post accusing a veterinarian of negligence. Two women who saw the post liked it and shared it. Both were ordered to pay a R$10,000 (approximately USD 4,500) fine by José Roberto Neves Amorim, a judge in the state of São Paulo. He explained his decision in the following terms: “there is responsibility for sharing messages.” |

In the context of this challenging environment for journalism and blogging, there has been a move to set out a number of protections and rights for the digital world. While this leaves many challenges for journalists offline, the possibility of a progressive online framework could start to transform the free speech and media freedom environment in Brazil. The movement for such a framework – which would soon be known as “Marco Civil da Internet”, literally Civil Rights Framework for the Internet in Portuguese – started in 2007. And in 2009, the ministry of justice partnered with the Center for Technology and Society of the Getulio Vargas Foundation, and with the direct participation of civil society in order to draft a bill.

Marco Civil: Promises and Compromises

The original draft of Marco Civil was aimed at protecting internet freedom of expression, speech and privacy, establishing safe-harbour protections for intermediaries and establishing the principle that access to the internet is a civil right. While largely positive, the approved text adopted and passed into law in April 2014 is substantially different than the version sent to Congress in 2011.

Early steps: consultation process – or the success of the multistakeholder approach

The consultation process at the origin of Marco Civil has been exemplary in many ways. Alessandro Molon, the MP rapporteur of the bill, endorsed a multistakeholder approach and accepted contributions from civil society, internet companies, the tech sector and academics as soon as the policy-making process kicked off. Internet users even had the opportunity to make suggestions via tweets. The participatory consultation process, the involvement of civil society and its influence upon the evolution of the bill, contributed in portraying Brazil as a “champion for transparency and multistakeholder approach”.[8]

A series of setbacks and obstacles: copyright, net neutrality, privacy/data localisation

However, as soon as the bill was first introduced to Congress in 2011, it faced a series of setbacks. First the copyright industry opposed the principle of court orders to take down content, and managed to introduce a provision asserting that notice and takedown procedures would apply for copyright infringement, thus escaping legal oversight. In practice, this would mean that copyright or related rights infringements holders would not require court orders to request content to be taken down and any

intermediary who fails to comply could be subject to civil liability damages.

Second, powerful telecom companies have strongly lobbied against the principle of net neutrality. The principle of net neutrality implies that all data should be treated equally and should be sent to their destination with equal speed. Net neutrality also helps to guarantee everyone’s right to express themselves freely within the limits set by the law and to access the content and services they desire, whether free or paid.[9] Under Marco Civil, internet service providers are barred from interfering with connection speeds or content. The framework around net neutrality, strongly backed by civil society, upset the interests of the country’s telecom companies. Their influence inside the Brazilian bicameral congress’s lower house was such that the vote on the bill was postponed and dropped from the legislative agenda on many occasions.

From 2012 to 2014, the bill was effectively on hold as a result of the telecoms industry’s intense opposition to the provision on net neutrality and other battles over intermediary liability, defamation and data retention. The stalemate was such that internet freedom advocates launched several campaigns denouncing telecom companies lobbying and claimed that Marco Civil was “under attack”.[10]

The bill did not have a momentum strong enough to bring it back to the top of the political agenda until June 2013. At the time, revelations on mass surveillance and the spying activities of the US National Security Agency (NSA) by whistleblower Edward Snowden had provoked international outrage. Brazil’s President Dilma Roussef was particularly vocal and even postponed her official visit to the US after the leaked documents revealed the US agency had been monitoring the president’s emails and phone calls, those of Brazil’s biggest oil company and the communications of millions of citizens.

Snowden’s revelations provided a window of opportunity for the government to push the bill forward and overcome the standstill in Congress. In September 2013, Roussef decided to put Marco Civil into a constitutional emergency process to accelerate its adoption by congress. Under Brazilian law, the congress must give priority to a bill placed under constitutional emergency and cannot examine or pass any other law until the vote on the bill in question is carried out.

While this move to push for the adoption of Marco Civil was very welcome, in the meantime, the government pressed for an amendment of Marco Civil that would oblige big internet companies such as Facebook, Google and other foreign service providers to base servers inside Brazil and be subject to Brazilian law. The set of measures was intended to extricate the internet in Brazil from the influence of the US and its tech giants, and in particular to protect them from the reach of the NSA – claiming to protect Brazilian citizens’ privacy. But forcing internet companies to host data pertaining to Brazilian citizens within Brazilian territory was extremely controversial: “forced localisation” sets a bad precedent as it is more often used by authoritarian regimes to block the internet and have access to internet users’ data. By offering these proposals, the Brazilian government has led some to draw a parallel with site-blocking in countries such as China, Iran and Bahrain, and many saw these proposals as too strong a remedy for the aim of providing protection from mass surveillance by the UK and US. Broadly rejected by civil society, engineers, companies and several legislators, the proposal was dropped by the government so that voting could take place.

| The final wording of the bill enshrines access to the web, guarantees neutrality and puts limits on the metadata that can be collected from internet users in Brazil. It also makes internet service providers not liable for content published by their users and requires them to comply with court orders to remove offensive material. However, it still has its blind spots, in particular the lack of guarantees for deleting data records, the introduction of special courts for defamation cases and the respect of “free business models” as a principle of the bill.The last two provisions are problematic as they are open to interpretation and might create precedent allowing, respectively 1) special treatment for public figures who want to take down content related to their “honour, reputation or rights of personality” and 2) businesses and particularly telecom companies to challenge the principle of net neutrality if deemed against their “business model”.[11]

As a whole, Brazil’s “internet bill of rights” is a progressive law and puts the country in another level in terms of freedoms of expression.

Marco Civil is considered by the global internet community as a one-of-a-kind bill, with the inventor of the world wide web Sir Tim Berners-Lee hailing the “groundbreaking, inclusive and participatory process that has resulted in a policy that balances the rights and responsibilities of the individuals, governments and corporations who use the internet”. |

Marco Civil: A landmark to export and replicate across Brazilian borders?

“Marco” means reference or landmark in Portuguese. The rapporteur of the bill, Alessandro Molon, insists on the potential of the bill to be an example and influence for other countries in Latin America and beyond. Indeed, as soon as Brazil signed Marco Civil into law, it became the largest country to enshrine net neutrality in its legal code, among its other welcome provisions on privacy, intermediary liability and accessibility and openness of the internet. When signing the bill into law on 23 April 2014, President Dilma Rousseff tweeted that Brazilian Marco Civil model “may influence the global debate in the quest towards the guarantee of real rights in the virtual world”.[12]

With Marco Civil passed into law, Brazil, in its domestic law, is asserting itself as a potential world leader in internet freedom. This could both make it a model for other countries to follow, and should give it more credibility and the ability to be one of the leaders on a progressive approach to internet governance at international level. However, aside from the caveats regarding the bill we have discussed above, access remains a key hurdle for Brazil.

The full report is available in PDF: [English] | [Portuguese]

Part 1 Towards an internet “bill of rights” | Part 2 Digital access and inclusion | Part 3 Brazil taking the lead in international debates about internet governance | Part 4 Conclusions and recommendations

— Footnotes

[1] Net neutrality or network neutrality is the principle that all internet users should be able to access any web content and use any application they choose without restrictions or limitation imposed by telecommunication providers. It is a founding principle of the internet which guarantees that telecom operators remain mere transmitters of information and do not discriminate between different users, their communication or content accessed. It means that all data should be treated equally and should be sent to their destination with equal speed regardless of who sends them or receives them. The internet rights campaigning group La Quadrature du Net fears that the undermining of net neutrality by operators who develop business models that restrict access may lead to an internet where only users able to pay for privileged access will enjoy the network’s full capabilities.

[2] Index on Censorship interview, 11 February 2014

[3] Index of Censorship interview with Abraji, Brazilian Association for Investigative Journalism, 11 February 2014. Data updated in April 2014

[4] Index on Censorship interview with Article 19 and Abraji, 11 February 2014; Committee to Protect Journalists report: Halftime for the Brazilian press. Will justice prevail over censorship and violence?, 6 May 2014; Freedom House report: Freedom on the Net 2013; Reporters Without Borders

[5] A takedown request refers to a demand from copyright owners, government or law enforcement agencies, or even individuals to remove, withhold or restrict access to content from the internet. An increasing number of companies (including, but not limited to Google, Facebook, Twitter, Dropbox, Yahoo and Microsoft) have decided to issue transparency reports in order to share information on the number of requests for user information and/or requests for user information and/or requests for removal/takedown received from governments, law enforcement agencies, copyright owners and sometimes third parties.

[6] Between January and June 2013, Google received a cour order to remove 107 blog posts

[7] The Committee to Protect Journalists reports that Pinto also blogs for Yahoo and has reported on drug trafficking, environmental devastation, and political and corporate corruption in the region for more than 45 years. He has been physically assaulted, threatened, and targeted with dozens of criminal and civil defamation lawsuits as a result of his investigative work. Brazilian journalist ordered to pay damages in libel case, CPJ, 31 January 2013

[8] Index on Censorship interview, Centre for Technology and Society, 14 February 2014

[9] The Enemies of Internet. Special Edition: Surveillance , Reporters Without Borders 2013 report

[10] The Brazilian institute for Consumer Protection launched the campaign #MarcoCivilJà (which means Marco Civil Now in Portuguese), condemning the procrastination of the bill at congress. Access Now launched an online petition called “Hands Off Marco Civil !”. A collaborative documentary project, Freenetfilm, campaigned for net neutrality and made a YouTube video that got 83,385 views.

[11] Article 20 §3 introduces special courts for cases “that deal with compensation for damages resulting from content on the internet related to the honour, reputation or rights of personality as well as with the takedown of such content by internet service providers”. Article 3 VII ensures that the use of the internet in Brazil has amongst its principles the respect for “free business models promoted on the internet, provided they do not conflict with other principles established in this law”. Geneva Internet Platform, Marco Civil and English translation

[12] “O nosso modelo de #MarcoCivil poderá influenciar o debate mundial na busca do caminho p/ garantia de direitos reais no mundo virtual”, tweet from President Dilma Rousseff official account, 23 April 2014

12 Jun 2014 | Cameroon, Iran, News, Nigeria, Russia

The 2014 World Cup in Brazil starts today, 32 nations preparing to battle it out across eight groups in the first stage of the tournament.

This year’s competition, like so many before it, comes with its designated group of death. For those not familiar with the lingo, it means the group containing the highest amount of strong teams. Or even more simply put, the group most difficult to progress from. (You can’t accuse the beautiful game of holding back on the melodrama).

Index has looked at the countries taking part in arguably the biggest show on earth, and put together our own group of death — the freedom of expression edition.

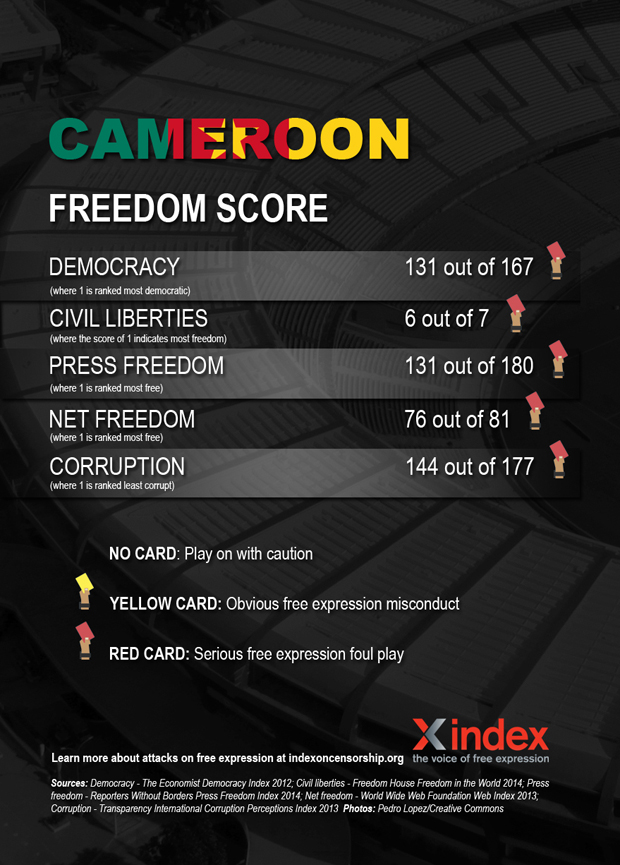

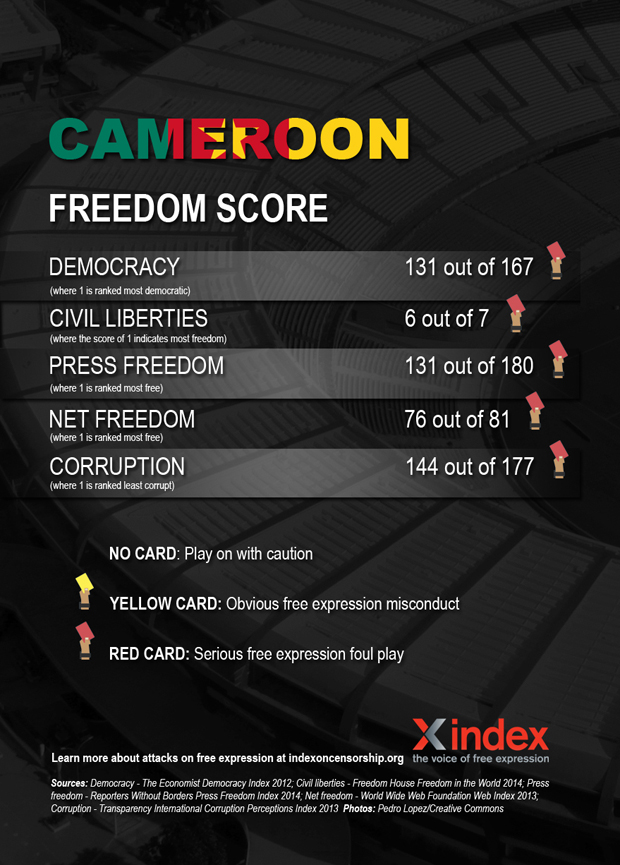

Cameroon

Cameroon — or the Indomitable Lions — have a solid track record in qualifying for the World Cup, having taken part seven time, more than any other African side. There were also the first African team to make it to the quarter final and are responsible for one of the most iconic moments in the tournament’s history. Their track record on free speech, however, is less impressive.

Freedom of expression is guaranteed in Cameroon’s constitution. Despite this, the government of Paul Biya — the country’s leader since 1982 — has been been accused numerous violations of free expression.

Large parts of the press are biased towards the ruling elite, while critical journalists face detainment, harassment and demands to reveal sources, among other things. Self censorship is widespread. In September 2013, 11 press outlets, including newspapers, radio stations and a TV station, were shut down for disrespecting “ethics and professional norms”. In 2010, former newspaper editor Germain Ngota, who had been investigating corruption allegations involving the state-run oil company, died in jail.

Freedom of assembly is often cracked down on. In 2012, former opposition presidential candidate Vincent-Sosthène Fouda and others were charged with “holding an unlawful demonstration”. The same year, security forces used tear against a crowd gathered to protest against Biya. In 2008, around 100 people were killed in clashes with police in anti-government riots.

Arts are not spared either. In 2013, Jean-Pierre Bekolo’s film Le President was banned in Cameroon because it discussed the end of Biya’s reign . In 2008, Lapiro de Mbanga, who criticised the constitutional change in term times that would allow Biya to stay in powers through song, was arrested.

Homosexuality is outlawed, and punishable by up to 14 years in prison. Human rights violations against LGBTI people, or those perceived to be, are “commonplace”. In July 2013, Eric Ohena Lembembe, director of the Cameroonian Foundation for AIDS (CAMFAIDS) was brutally murdered, in what friends suspect was an attack based on his pro-LGBTI advocacy.

Iran

Team Melli will hope that their fourth appearance at the World Cup will see them progress from the group stages for the first time. When he was elected almost a year ago, there was hope that President Hassan Rouhani would be a progressive force within Iran. The results so far have been mixed.

Since coming into power, Rouhani has taken some steps to improve press freedom, such as withdrawing 50 motions against journalists, and lifting some restrictions on previously banned topics. However, the government still controls all TV and radio, and censorship and self-censorship is widespread. The latest figures put the number of jailed journalists in Iran at 35. In January 2013, a group of journalists were arrested for allegedly cooperating with “anti revolutionary” news outlets abroad. Journalists’ associations and civil society organisations that support freedom of expression have also been targeted.

The internet and social media played a significant part in publicising and documenting the protests that followed the 2009 election, which many Iranians believed was fraudulent. The regime has banned Facebook, YouTube, Twitter and, recently, Instagram. The lead-up to the 2013 elections saw Iranian leaders tightening access to the web, and silencing “negative” news. While Rouhani — seemingly an avid Twitter user — has indicated plans to relax web censorship, the country’s plans to launch a “national internet” are said to be going ahead.

In May, eight people were jailed on charges including blasphemy, propaganda against the ruling system, spreading lies insulting the country’s supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei on Facebook. Recently, a group of young people were arrested over a video posted of them singing and dancing along to the song “Happy”, which police called was a “vulgar clip” that had “hurt public chastity”. Some commentators believe the move was meant to intimidate Iranians and discourage online criticism.

Nigeria

Brazil 2014 marks 20 years since Nigeria’s first outing at the World Cup, and the Super Eagles arrive at the tournament as reigning Africa Cup of Nations champions. The country’s leadership, however, is not a champion of free expression.

While parts of Nigerian media is controlled by people directly involved in politics, the country can also boast a lively independent media sector. However, journalists, especially those covering sensitive topics such as corruption or separatist and communal violence still face threats. Journalists have been arrested by security forces, and media outlets have been attacked by terrorists. Legal provisions such as sedition and criminal defamation also challenge press freedom. In 2011, a journalist was arrested over stories detailing alleged corruption in the Nigerian Football Federation.

The country’s freedom of information act was put in place in 2011. However, when human rights lawyer Rommy Mom tried to use the legislation to trace some 500 million of missing aid money allocated to his flood ravaged home state of Benue, he was met with threats from people connected to the state governor, and was forced to flee.

The Same Sex Marriage Prohibition Act 2013 outlawing gay marriage and relationships, was signed into law by President Goodluck Jonathan in January. The unpublished law makes it illegal for gay people to hold meetings, and outlaws the registration of homosexual clubs, organisations and associations. Those found to be participating in such acts face up to 14 years in jail.

Nigeria has come under international attention in recent months for abduction of the Chibok school girls by terrorist group Boko Haram. Among other things, Nigerians responded with the powerful #BringBackOurGirls campaign. In June however, authorities seemed to ban an offline protest against the kidnappings, before quickly backtracking. It is also worth noting that the Nigerian government has targeted journalists in their “war on terror”.

Russia

Team Sbornaya travel to Brazil in the knowledge that next time in the World Cup rolls around, they will be playing on home soil. Russia of course, recently hosted another international sporting event — the 2014 Winter Olympics. However, global attention did not improve the country’s poor record on freedom of expression. In fact, experts predicted a rise in censorship ahead of the Olympics.

Press freedom has long been under attack by Russian authorities, with TV news currently providing little beyond the official government line. In the last few months, the relatively well-respected TV channel RIA Novosti was liquidated following a decree by President Vladimir Putin, and replaced by a new press agency headed by a Kremlin-loyalist. In January, Dozhd, a popular independent TV channel was dropped by satellite and cable operators over a controversial survey. For the remaining critical journalists, Russia — one of the countries with the highest number of unpunished journalist murders — is a dangerous place to work.

The crackdown on the internet is widely believed to have started with the protests surrounding the elections securing Putin’s third term in power, organised partly through social media, but it has recently intensified. The Duma has adopted controversial amendments to an information law, targeting bloggers with blocking and fines for anything from failing to verify information posted, to using curse words. Also recently, the founder of “Russian Facebook” VKontakte says he was forced out, with the son of the head of Russia’s largest state-run media corporation predicted to take over as CEO. In 2013, the Duma approved legislation allowing immediate blocking of websites featuring content deemed “extremist”.

Public protests are discouraged through forceful responses by police, arrests, harsh fines and prison sentences. The country’s recent anti-gay legislation also pose a big threat to free expression and assembly. The ban on “promotion” of gay relationships, means that any form of expression deemed to be “gay propaganda” can be shut down. The law has also lead to physical attacks on Russia’s LGBT population.

An earlier version of this article stated that Brazil 2014 marks ten years since Nigeria’s first outing at the World Cup. This has been corrected.

This article was published on June 12, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

![Read the full report in PDF: [English] | [Portuguese]](https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/brazil-cover.jpg)