30 Oct 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, mobile, News and features, Serbia

The Association of Serbian Journalists reports that since 2013 there have been 65 attacks on Serbian journalists. Assailants in 11 of the incidents — around 17% of cases — have been prosecuted.

Believe it or not, a 17% conviction rate could be considered good news. But it isn’t enough.

International media organisations routinely assess that fewer than 10% of crimes committed against journalists worldwide result in prosecution. While the cavalier attitude by law enforcement and authorities to go after criminals gave rise to the phrase “impunity from prosecution,” many of us wonder if the term “immunity” might be more apt.

And that’s why I welcomed the initiative of Serbian authorities who, in early 2014, established a commission to support investigations into the deaths of Serbian journalists dating back to 1994, including Dada Vujasinović, Slavko Ćuruvija and Milan Pantić. In order to highlight the importance of their work and to raise the awareness of the importance of fighting impunity, my office supported the commission’s Chronicles of Threats campaign.

Ćuruvija, the owner of the newspaper Dnevni Telegraf and the magazine Evropljanin, was gunned down in front of his home in Belgrade in 1999. Thanks in part to the work of the commission, authorities re-opened the case last year and put four former state security officials under investigation for his murder. A trial is underway and while this is a start, his family and fellow journalists still need to see results.

This is why I why I wholeheartedly support all consciousness-raising efforts that take place on November 2 each year – the United Nations proclaimed International Day to End Impunity for Crimes Against Journalists which was initiated in 2013.

This landmark UN resolution condemns attacks on journalists and other media members. It also urges countries to do their utmost to prevent violence and make perpetrators accountable for their crimes, in order to promote a safe working environment.

But setting aside a day to cajole authorities to take the crimes against media seriously can only go so far. That is why the modest successes of the commission in Serbia provide a glimmer of hope that justice can be served.

But in order for societies to provide that safe working environment envisioned by the UN, a systematic array of steps must be undertaken at the local and national level. None of these steps are easy and their ability to succeed is questionable.

To begin with, local officials must be given the financial resources to conduct thorough investigations of all crimes committed. This is no small task in many of the 57 countries that comprise the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe — the region in which I work. Many of these nations have economies in transition, tax revenues are scarce and it’s a hard sell for authorities to suggest earmarking money to find justice for one class of victims when the needs of the whole community are not being adequately served.

Prosecutors and judges also need to be adequately trained to understand the importance of the fair application of existing criminal laws, especially when the rule of law in society is often buttressed only by a robust and independent media. This is the same media which is often critical of the prosecutors and judges who make up the judicial hierarchy.

In the end, getting past those hurdles may be seen, in retrospect, as the easiest steps. Because what’s really necessary to create a safe working environment is for society as a whole to accept that good journalism is necessary for a good society.

People must recognise that the free flow of information and ideas is essential in dynamic cultures and the secrecy and repression are antithetical to freedom and prosperity.

Creating a society where good journalism can flourish starts with making sure journalists can do their jobs and live to talk about it. And that means making sure that those who would run roughshod over journalists pay for their crimes.

This article was posted on 30 October 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

30 Oct 2015 | mobile, News and features, United States

(Photo: Erica Jong)

There have always been sexual rebels.

In the 18th century, Mary Wollstonecraft and her daughter, Mary Shelley, were fiercely rebellious about sexuality. They also were great feminists. In the 20th century, Emma Goldman spoke for women who believed love should be free.

Our age tends to divide things by decades and generalise about them. So, it’s assumed that the 70s and the second wave of feminism introduced sexual freedom to women. This is absolutely not true. If you read The Group by Mary McCarthy (1963), Tropic of Cancer by Henry Miller (1934), or Ulysses by James Joyce (1922), you see that sexual rebels have always been with us.

What was different about [my 1973 novel] Fear of Flying was that it was a book that tried to reveal how women thought about sex in an age when most books about women didn’t show this. So, when the book came out both women and men were shocked. Some said: “Women don’t think like this!” and some said: “Thank God, somebody is talking about how women really think!” What was fascinating to me as an author was how contradictory the responses were.

I always wanted to write the books for women that did not exist. There is a huge gap between what we write about and what we think about. I wanted to rip the top of the head off a lusty woman and expose her fantasies to the light. Fantasies are important but they don’t necessarily have to become realities. The zipless fuck was a fantasy of perfect idealized sex with a stranger, but it is often impossible to fulfill. Many readers missed that.

Now I see woman writers writing about bondage and discipline, cruelty and submission, and I wonder whether that is fantasy too. I’ve never been much interested in submission, so I read these books as fairytale fantasies for women.

I think it’s important not to take literature literally. We turn to writers to document our dream lives. We turn to writers to show us what we are afraid to show ourselves. Many writers who become known for sexuality are not that different from you and me. They have a need to reveal the unconscious mind. If we take them literally, we miss the point.

The big change in sexual writing happened in the 1960’s when books like Lolita and Tropic of Cancer were liberated by the courts. The change in literature emerged from the change in the law. Male writers got very excited and produced books like John Updike’s Couples (1968) and Philip Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint (1969). Suddenly it was possible to publish these very honest works. I wanted to show honesty from a woman’s point of view. I was not advocating a kind of behavior, but many people did not understand that.

In Fear of Dying, I have also been attempting to reveal something unrevealed before. An editor once told me there had never been a bestseller about a woman over 40. But as I watched women growing older, still feeling sexy, looking for a way to overcome mortality, I realised that we needed new books that showed how women had changed.

Like Fear of Flying, Fear of Dying is such a book.

Erica Jong is a novelist whose works include Fear of Flying and the newly-published Fear of Dying. (Her books are available on Amazon, iTunes, Waterstones or your local independent bookshop.)

This article was originally published on FeedYourNeedtoRead.com and is reposted here with permission.

|

From the summer 1995 Index on Censorship magazine

Deliberately lewd

Erica Jong explains why pornography is to art as prudery is to the censors

Pornographic material has been present in the art and literature of every society in every historical period. What has changed from epoch to epoch – or even from one decade to another – is the ability of such material to flourish publicly and to be distributed legally. After nearly 100 years of agitating for freedom to publish, we find that the enemies of freedom have multiplied, rather than diminished.

Read the full article |

30 Oct 2015 | Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan News, mobile, News and features

Photo: Aziz Karimov

Azerbaijani citizens are set to go to the polls this Sunday to vote for their representatives in 125 parliamentary districts, but this process will be far from democratic. This country has not held a democratic election for more than 20 years, and Azerbaijan’s parliament, the Milli Mejlis, is little more than a rubber-stamping body. These elections also take place against a backdrop of unprecedented repression as well as recent criticism from international bodies.

The leadership of the OSCE parliamentary assembly has recently cancelled a planned observation mission to the upcoming parliamentary election. And the OSCE parliamentary assembly’s democracy and human rights chairperson, Isabel Santos, said this week: “The Azerbaijani government’s crackdown on independent and critical voices has a particularly damaging effect ahead of the country’s 1 November parliamentary elections.”

“On the eve of parliamentary elections, when independent voices are crucial for having an informed debate about the country’s direction, Azerbaijani citizens will especially suffer from the silence their government has imposed,” Santos said.

A recent European Parliament statement said it expressed its “serious concern as to whether the conditions are in place for a free and fair vote on 1 November 2015, given that leaders of opposition parties have been imprisoned, media and journalists are not allowed to operate freely and without intimidation, and a climate of fear is prevalent”.

In addition to the OSCE parliamentary assembly, the OSCE’s office for democratic institutions and human rights as well as the European Parliament have also taken the unprecedented step of cancelling their election-monitoring missions to Azerbaijan.

There are now dozens of political prisoners in Azerbaijan, including prominent journalists, bloggers, human rights defenders, politicians, youth activists, and others who dared to express opinions critical of the ruling regime. Young journalist Rasim Aliyev, Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety chairman, was tragically murdered in August, and there appears to be no hope of justice in his case. Independent media continue to be ruthlessly targeted, in particular online television station Meydan TV, whose staff and their relatives have been facing extensive pressure ranging from threats to detention.

As detailed in a new report from the Sport for Rights campaign group, No Holds Barred: Azerbaijan’s Human Rights Crackdown in Aliyev’s Third Term, this brutal crackdown started with the re-election of President Ilham Aliyev to a third term in October 2013. In the two years that followed, the Aliyev regime aggressively targeted its critics, starting with those who told the truth about that fraudulent election, then moving on to the human rights defenders working to defend the rights of those political prisoners.

Although the election’s results may be a foregone conclusion, they do have political significance for Azerbaijan’s international relations. As the Sport for Rights’ report details, during Aliyev’s third term Azerbaijan’s relations with key international bodies have sharply deteriorated – in particular, the OSCE and the European Parliament.

This move was a serious blow to the Aliyev regime, which needs international observers to lend an air of legitimacy to what can only be an illegitimate vote.

The Aliyev regime should think carefully about how to proceed, before this damage to its international relations becomes irreparable. Something the Azerbaijani leadership does not seem to have realised is that the affirmation it is seeking from these international bodies – and indeed, the good public relations it seeks – cannot be bought. But real steps towards democratic reform would, in turn, generate more positive coverage of the country, not to mention genuinely improve its standing with international bodies.

Whilst it is too late to salvage Sunday’s parliamentary elections, it is not too late for the ruling Azerbaijani regime to right the serious wrongs being perpetrated in the country and to repair its relations with international bodies. Immediately and unconditionally releasing political prisoners would be an excellent – and very welcome – start.

This article was posted on 30 October 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

29 Oct 2015 | Events

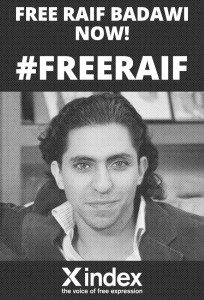

Saudi Arabian blogger and activist Raif Badawi is the winner of this year’s Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought, awarded by the European Parliament.

Saudi Arabian blogger and activist Raif Badawi is the winner of this year’s Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought, awarded by the European Parliament.

Badawi, who also won 2015 PEN Pinter Prize for an International Writer of Courage, was convicted in May 2014 for insulting Islam and founding a liberal website. He received a fine of 1 million riyals (£175,000) and a ten-year prison sentence. In addition, the court in Jeddah sentenced him to 1,000 lashes.

On 9 January 2015, after morning prayers, Badawi was flogged 50 times, but subsequent floggings have been postponed. Earlier this week however, Raif Badawi’s wife Ensaf Haidar, was informed that the floggings were to resume.

Meanwhile, his lawyer and brother-in-law Waleed Abulkhair is serving 15 years in prison for his peaceful activism.

Index calls for the immediate release of Raif Badawi and Waleed Abulkhair. Together with English PEN and fellow campaign organisations, we support “We Are Raif: a campaign for free speech and human rights in Saudi Arabia“.

Please join us in front of the Saudi embassy in London on Friday 30 October, from 9am. Activists are asked to meet at the Curzon Street entrance to the Embassy of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Mayfair, London.

When: Friday, 30 Oct, 2015, from 9am

Where: Saudi embassy in London, Curzon Street entrance (note: the postal address of the Embassy is 30-32 Charles Street).