10 Aug 2015 | Magazine, mobile, United States

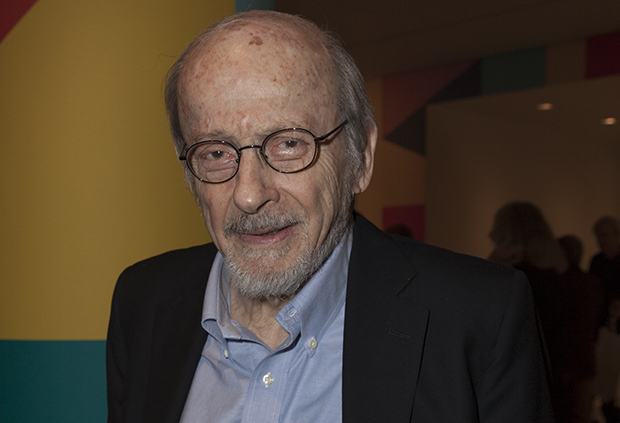

Edgar Lawrence Doctorow, a supporter of Index on Censorship, passed away on 21 July 2015 at 84.

A lifelong champion of free expression and considered one of the greatest novelists of the twentieth century, Doctorow’s passing comes at a time when freedom of speech is being challenged across the USA, from no-platforming in universities to the banning of books and materials.

Doctorow was born to second-generation Russian Jewish parents in the Bronx, New York, an area he loved and one which formed the basis for many of his novels. He had his first literary work published while still a teenager in his high school magazine and went on to study with the poet John Crowe Ransom at Kenyon College, Ohio, where he majored in philosophy.

He started his literary career in publishing but began writing novels in the late 1960s. His first published work was The Book of Daniel, a fictional account of the trial and execution of convicted US communists Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, written from the viewpoint of their children. Ragtime, his next novel, was published in 1975 and is considered his best, named at number 86 in the top 100 American novels of the twentieth century by the Modern Library editorial board. A work of historical fiction, Ragtime focuses on a wealthy family in early twentieth century New York. He went on to pen nine further books, three more of which were award-winners (World’s Fair, Billy Bathgate and The March), and in 2014 he won the Library of Congress Prize for American Fiction.

Doctorow championed numerous causes promoting the right to global freedom of expression. In the January 1988 issue of Index on Censorship magazine, he was noted, along with a multitude of other American writers, as having been monitored extensively by the FBI due to his works being considered, “subversive, suspicious or unconventional”. In the late 1980s, he was on the board of the Fund for Free Expression, New York, who assisted and supported Index’s work.

Later in life, in 2013, he was one of over one hundred signatories on a letter calling on the Chinese government to respect its population’s right to freedom of expression, and he was heavily involved with the work of PEN America, serving on their board and judging at their literary awards. He refused to be silenced in his efforts to draw the world’s attention to the plights of censored writers until his death.

7 Aug 2015 | Bangladesh, Campaigns, mobile, Statements

Index on Censorship deplores the killing of blogger Niloy Chakrabarti in Dhaka, Bangladesh, and calls on the authorities to investigate the murder and ensure that those responsible are found and brought to justice.

“We strongly condemn Niloy Chakrabarti’s brutal murder,” said Index’s senior advocacy officer Melody Patry. “We fear the death toll will increase if the authorities fail to take action to find and punish those responsible. Freedom of expression is in danger and Bangladesh must do more to protect writers online and offline.”

Chakrabarti, who wrote under the pen name Niloy Neel, is the fourth secular blogger to be murdered since the start of the year. A member of Bangladesh’s Science and Rationalist Association, he was attacked in his home in Dhaka.

In May, Ananta Bijoy Das was attacked and killed with machetes. On 30 March writer Washiqur Rahman, who was also known for his atheist views, was stabbed to death. In February, fellow atheist Avijit Roy was hacked to death by a knife-wielding mob in Dhaka as he walked back from a book fair.

Niloy Neel – Died 7 August 2015; killed in his flat in Dhaka, capital of Bangladesh. Neel was an anti-fundamentalist and anti-extremist blogger, and a known atheist who’d written pieces critical of religion. Other causes he wrote on were the rights of ethnic minorities and women. He was a regular contributor to Mukto-mona and Ishtishon. Currently, he was an activist of the Ganajagaran Mancha, the platform demanding capital punishment for the 1971 Islamic war criminals who’d recently been sentenced to life imprisonment in Bangladesh. He was murdered by an Islamic fundamentalist gang.

Ananta Bijoy Das – Died 12 May 2015 in Sylhet, Bangladesh. Das reportedly wrote for “Mukto-Mona” (“Free-mind”), and his pieces were often critical of religion. Islamist groups stated that his murder was a punishment for “crimes against Islam”. Das sought to be less controversial in his writing but death threats increased against him as more and more bloggers were being murdered. One of his last posts was critical of Bangladeshi police and how they did not protect secular writers. Also a Ganajagaran Manch activist.

Washiqur Rahman – Died 30 March 2015 in Dhaka. Rahman was targeted for his anti-Islamic writing, as told to police by the suspects taken into custody for the murder. Rahman frequently criticized what he saw as irrational fundamentalist groups; he was not an atheist by any means, but he held different religious views than his more extremist attackers. He was said to have written a 52-episode series for an anti-religion satirical site called Dhormockery.com which mocked aspects of Islam. He was also a Ganajagaran Manch activist.

Avijit Roy – Died 26 February 2015. Bangladeshi born US national. Roy founded the Mukto-Mona website, and his pieces often criticized religious intolerance. He was also a known advocate for freedom of speech in Bangladesh and would organize protests against international censorship and imprisonment of bloggers. Islamic militant organization Ansarullah Bangla Team claimed responsibility for the attack. He also was involved with the Ganajagaran Manch.

7 Aug 2015 | mobile

6 Août 2015

Les organisations soussignées œuvrant pour la liberté de la presse, le développement des médias et les droits humains dénoncent les attaques continues et les menaces contre les journalistes, le personnel des médias et les défenseurs des droits humains, notamment les récents incidents graves durant lesquels le défenseur des droits humains Pierre Claver Mbonimpa a survécu à une tentative d’assassinat tandis que le journaliste Esdras Ndikumana a été victime d’une attaque brutale de la part d’agents de la police et des renseignements.

Nous sommes très préoccupés par le maintien de la fermeture des radios indépendantes ainsi que le manque d’accès à une information fiable au Burundi. Cela est particulièrement inquiétant étant donné la dégradation continue de la situation sécuritaire du pays – un contexte dans lequel chaque Burundais devrait avoir accès à une information correcte et objective plutôt que de devoir se fier à des rumeurs.

Nous appelons les autorités burundaises à enquêter sur ces attaques immédiatement et de s’assurer que les responsables soient traduits en justice dans le cadre d’un procès équitable. De plus, nous demandons aux autorités de permettre la réouverture et le fonctionnement des médias indépendants et de les autoriser à opérer depuis la Maison de la Presse ou d’un autre endroit selon leurs décisions et capacités. Ceci est particulièrement important étant donné que plusieurs stations de radio ont été détruites. Nous encourageons également les autorités à autoriser et faciliter la reconstruction et le rééquipement de ces radios.

Nous encourageons les autorités à assurer le retour en toute sécurité de la cinquantaine de journalistes et personnel des médias qui ont quitté le pays et cherché refuge dans des pays voisins. Nous demandons également aux autorités de s’assurer que ces journalistes puissent recommencer à travailler sans crainte de poursuite ou de persécution.

Enfin, nous appelons à un dialogue entre les autorités et les médias, entre les autorités et les partis de l’opposition ainsi qu’entre les autorités et les Nations Unies et les représentants de l’Union Africaine afin de créer les conditions menant à la construction d’un environnement propice à la paix pour tous les Burundais.

Signataires :

Henry Maina, Directeur Général, Afrique de l’Est, ARTICLE 19

Tom Henheffer, Directeur Exécutif, Canadian Journalists for Free Expression (CJFE)

Toby Mendel, Directeur Exécutif, Center for Law and Democracy

Courtney Radsch, Directrice du Playdoyer, Committee to Protect Journalists

Caroline Vuillemin, Directrice des Opérations, Fondation Hirondelle

Ruth Kronenburg, Directrice, Free Press Unlimited

Daniel Calingaert, Vice Président Exécutif, Freedom House

Daniel Bekele, Directeur Afrique, Human Rights Watch

Melody Patry, Responsable du Plaidoyer, Index on Censorship

Ernest Sagaga, Chargé des Droits de l’homme et de la Communication, International Federation of Journalists (IFJ)

Jesper Højberg, Directeur Exécutif, International Media Support (IMS)

Barbara Trionfi, Directrice Exécutive, International Press Insitute (IPI)

Elisa Lees Munoz, Directrice Exécutive, International Women’s Media Foundation (IWMF)

Karin Deutsch Karlekar, Directrice, Free Expression Programs, PEN American Center

Tamsin Mitchell, Chercheur Afrique, PEN International

Cléa Kahn-Sriber, Responsable du bureau Afrique, Reporters sans Frontières

Tina Carr, Directrice, Rory Peck Trust

Ronald Koven, Directeur Adjoint, World Press Freedom Committee

7 Aug 2015 | Art and the Law Commentary, Artistic Freedom Commentary and Reports

The 112 young cast members were two weeks into rehearsal when the production was cancelled. (Photo: Helen Maybanks / National Youth Theatre)

Reports this week that the National Youth Theatre had pulled the plug on Homegrown, a new play about radicalisation, contained some discomfiting details. The production had been moved from a venue in Bethnal Green, east London, amid concerns it was “insensitive”. Police had apparently requested a final draft of the script, and there had been talk of plain-clothes police attending performances. The play is the latest victim of an encroaching nervousness among authorities and arts organisations.

In September last year, the arts world was blindsided by the closure of white South African artist Brett Bailey’s Exhibit B exhibition at the Barbican. Bailey’s controversial work featured live actors in tableaux mimicking the anthropological exhibits of the 19th century, when real people were exhibited as curiosities for the amusement of Europeans – people such as Saartjie Baartman, the “Hottentot Venus”.

Bailey presents his show as antiracist and anticolonial. This newspaper agreed, giving it five stars during its Edinburgh run, and praising Bailey’s “fearlessly uncompromising” approach. Others took a diametrically opposed view. Sara Myers, a journalist in Birmingham, started Boycott the Human Zoo, an online petition, supported by a broad coalition of campaigners, artists and arts organisations, condemning the work and calling for it to be cancelled. On the opening night in London, protesters gathered to picket the show. Accounts differ as to what happened next, but the evening ended with police advising that Exhibit B be shut down, and not reopened. The Barbican felt they had no alternative but to follow the advice.

The Exhibit B closure may have been unexpected, but it was not unprecedented. Last year in Edinburgh, pro-Palestinian and pro-Israel supporters protested outside The City – a hip-hop musical by Israeli company Incubator that received funding from the Israeli government. There, again, the police advised the venue to cancel the show. And as far back as 2004, the West Midlands police similarly advised Birmingham Rep to cancel Gurpreet Kaur Bhatti’s play Behzti about abuse and corruption in a Gurdwara (Sikh temple), when protesters from the Sikh community, who had demonstrated outside the theatre for several days, tried to break into it. It was Bhatti’s subsequent play, Behud, an imaginative response to the experience of having Behtzi cancelled, that provided the point of departure for an ongoing programme of work looking at constraints on freedom of expression in UK that I started at Index on Censorship.

At the start of that programme, I wrote a case study of the premiere production of Behud at the Belgrade theatre in Coventry called Beyond Belief – theatre, freedom of expression and public order. Given the controversy surrounding Behzti, Behud was treated as a potential public order issue from day one. Importantly, it revealed that there was, and there remains, no specific guidance for policing of artistic freedoms. It also spawned a series of roundtable discussions and a couple of conferences on the status of artistic freedom, the second of which, Taking the offensive at the Southbank Centre in 2013, looked at how lack of clarity around policing roles and the law contributed to growing self-censorship in the cultural sector. Coming out of this conference was a picture of self-censorship as pervasive, complex and troubling, and there was a clear call for guidance to navigate an increasingly volatile cultural landscape. Specifically, many arts professionals who attended the conference were unclear about the role of the police and largely ignorant of the laws that impact on what is sayable in the arts.

This is no surprise – for several reasons. There is no training for arts professionals in art and the law as part of tertiary education. There is also very little in the way of legal precedent to guide arts organisations. And, of course, freedom of expression is innately complex. The right to it includes the right to shock, disgust and offend. But it is also not perceived as an absolute right, as demonstrated in the long list of qualifications in Article 10 of the European convention on human rights where freedom of expression is qualified by concerns including national security, the prevention of disorder and the “protection of health or morals”. It is therefore unsurprising that arts organisations can be unsure about how best to defend their right to free expression.

Tamsin Allen, senior partner at law firm Bindmans, and I decided to do something to help and have produced a series of information packs for arts organisations that introduce the law in a way that is relevant and tailored to their needs. The guides contextualise and explain qualifications to free expression, how they are represented in our legislation and what they mean for artists and arts bodies.

Choosing five areas of law that address these protected areas – legislation covering child protection, counter terrorism, public order, obscenity and race and religion – the lawyers explain the offences, and the roles and responsibilities of police and prosecuting services, as well as those of artists and arts bodies. However, it is the pack on public order that is probably most relevant to the arts sector, because it is far more likely that a public order problem arises because of the reactions of third parties to the work of art. This reflects how the art we see is much more subject to social rather than legal controls, and that is where the police come in, to arbitrate over the public space where some deep-seated social conflicts are acted out.

The packs explain that the police have a duty to support freedom of expression and to protect other rights, to prevent crime and to keep the peace. They summarise relevant legislation, explaining the qualified nature of the right to freedom of expression due to the offences in each area of law, and give guidance how best to prepare if you think the work could be contested. The guidance encourages arts organisations to be prepared to defend work they believe in, advises them on when and how to involve the police and on how to anticipate potential problems, guided as much by good practice and common sense as a detailed understanding of the law, most of which most organisations and artists will be doing anyway.

The packs are not a substitute for legal advice and provide links to law firms willing to give advice on this area. It includes a series of case studies that consider recent examples of police and/or lawyers having been involved in an artistic event, which look at things that worked well for freedom of expression and things that didn’t.

However, we have a problem. The heckler’s veto is working. When faced with a noisy demonstration, the police have shown that they will all too often take the path of least resistance and advise closure of whatever is provoking the protest. Arts organisations may have prepared well, and yet still find themselves facing the closure of a piece of work. This sends out a disturbing message to artists and arts bodies – that the right to protest is trumping the right to freedom of artistic expression. As things stand, in the trigger-happy age of social media where calls for work that offends to be shut down are easily made and quickly amplified, the arts cannot count on police protection to manage both the right to protest and to artistic expression. The police did a risk assessment on Behud and asked for £10,000 a night to provide adequate protection. Hamish Glen, artistic director of the Belgrade, explained that this was a fiscal impossibility – so the police offered to halve it, eventually waiving the fee altogether once Glen pointed out that even half was prohibitive and represented de facto censorship. But it exposed the fact that there is no guidance around the policing of artistic expression as a core duty, leaving it vulnerable. The fees were calculated based on how the police charge for attending football matches and music festivals. I have not heard of an arts venue being asked to pay for policing before.

In an ideal world we would have access to both the artwork and the protest it provokes. This is when art really works for society, when it encourages debate, inspires counterspeech; art coming from all perspectives and all voices in society, in particular those who are currently shamingly mis- or underrepresented in contemporary culture.

If we are to create the space where artists are free to take on the more complex issues in society, that may be disturbing, divisive, shocking or offensive, then we need to look again at the role of the police in helping to manage the public space in which different views meet. These may in fact be the same issues that the police are called on to manage through community relations policing, and this only adds to the complexity of their role – they probably would prefer it if artists didn’t rock the boat. And they can point to being resource-strapped and under pressure to fight crime.

The situation raises a series of difficult and important questions about policing, art and offence and requires high-level discussion, involving the police of course, about how best to defend the right to free expression. That work needs to start now.

A version of this article originally appeared in The Guardian on 7 August 2015