21 May 2015 | Angola, mobile

Journalist and human rights activist Rafael Marques de Morais (Photo: Alex Brenner for Index on Censorship)

The trial of Index award winning investigative journalist Rafael Marques de Morais ended 21 May 2015 after the charges were dropped.

“Great news indeed,” Marques de Morais told Index.

“In light of a number of free speech concerns in the region, it’s vital that the charges against Rafael Marques de Morais have been dropped. Rafael’s crucial investigations into human rights abuses in Angola should not be impeded,” said Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg.

Marques de Morais was being sued for libel by a group of generals in connection to his work exposing corruption and serious human rights violations connected to the diamond trade in his native Angola.

The case was directly linked to Marques de Morais’ 2011 book Blood Diamonds: Torture and Corruption in Angola. In it, he recounted 500 cases of torture and 100 murders of villagers living near diamond mines, carried out by private security companies and military officials. He filed charges of crimes against humanity against seven generals, holding them morally responsible for atrocities committed. After his case was dropped by the prosecution, the generals retaliated with a series of libel lawsuits in Angola and Portugal.

Marques de Morais originally faced nine charges of defamation, but on his first court appearance on 23 March was handed down an additional 15 charges. The proceedings were marked by heavy police presence, and five people were arrested. The trial opened just days after he was named joint winner of the 2015 Index Award for journalism.

The parties had been negotiating to try and find some “common ground”, Marques de Morais told Index in late April, but the talks broke down. His case was postponed to 14 May while the talks were ongoing.

The resumption of the trial came amid allegations of a massacre of members of a religious sect that Marques de Morais reported on for The Guardian. MakaAngola, Marques de Morais’ investigative journalism site, was knocked offline for a short period after The Guardian article.

This article was posted on 21 May 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

21 May 2015 | Events, mobile

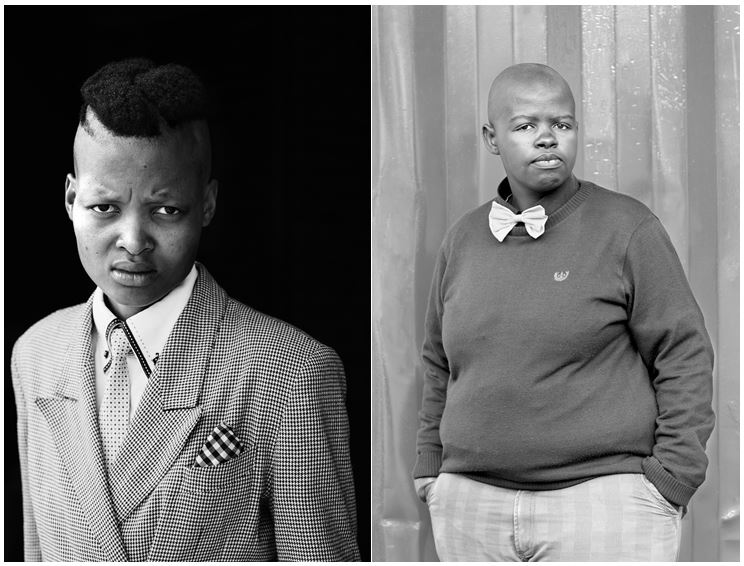

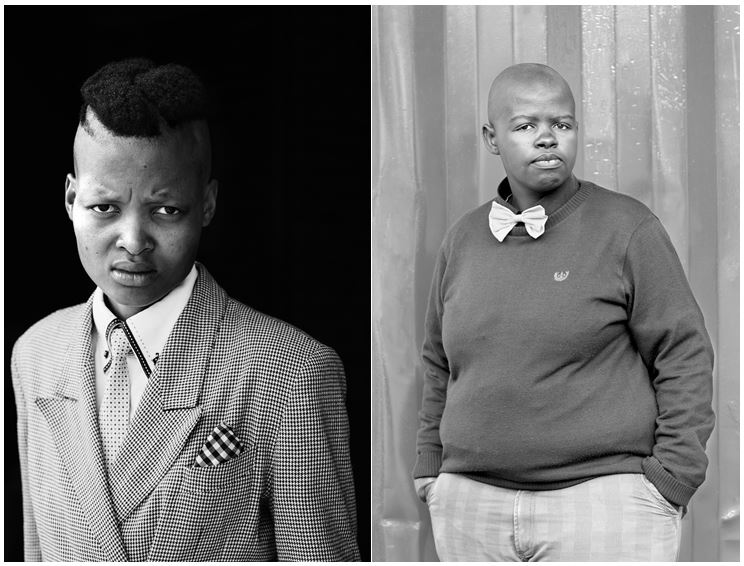

South African photographer and human rights campaigner Zanele Muholi won the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Arts Award in 2013.

Writer, campaigner and broadcaster Bidisha joins her in London to discuss the power of art in activism and the importance of visibility and representation in combating prejudice and human rights abuse.

Zanele will also be discussing her Deutsche Börse Photography Prize 2015 nominated work Faces and Phases which is currently on display at The Photographers’ Gallery, London (17 Apr – 7 Jun) and at the Brooklyn Museum, New York (1 May – 1 Nov)

WHEN: Tuesday 26th May 2015, 6.30pm

WHERE: London College of Fashion, London, W1G 0BJ

TICKETS: £12 with promo code PGMEMBER (normally £20) / available here

21 May 2015 | mobile, News, United Kingdom

In the dark times, will there also be singing?

Yes, there will be singing.

About the dark times.

– Bertolt Brecht

In an address to the first conference convened by the International Writers Center, held in St Louis in 1996, American poet Carolyn Forché described the ordeal of Hungarian poet Miklós Radnóti, who was forced into slave labour during World War II.

Radnoti managed to secure a small notebook in which he recorded his experiences in 10 poems written before he was executed.

A coroner’s report written when his body was exhumed after the war recorded:

“A visiting card with the name Dr. Miklós Radnóti printed on it. An ID card stating the mother’s name as Ilona Grosz. Father’s name illegible. Born in Budapest, May 5, 1909. Cause of death: shot in the nape. In the back pocket of the trousers a small notebook was found soaked in the fluids of the body and blackened by wet earth. This was cleaned and dried in the sun.”

Forché noted that the story of Radnoti did not end in a mass grave. Rather, his work, like that of others survived as “evidence of the dark times in which they lived”. This is what Forché calls “the poetry of witness”, work forged in instances and circumstances when the “personal” and “political” cannot be kept separate.

I was reminded of Forché and her concept of witness when I read the reactions to the court decision that would finally allow pianist James Rhodes to publish his memoir, Instrumental.

Rhodes’s candid book detailed his sexual abuse at the hands of a teacher. He had been raped, leaving him with spinal damage. An extract from the book published on the Guardian website describes the horror and the aftermath:

“I went, literally overnight, from a dancing, spinning, gigglingly alive kid who was enjoying the safety and adventure of a new school, to a walled-off, cement-shoed, lights-out automaton. It was immediate and shocking, like happily walking down a sunny path and suddenly having a trapdoor open and dump you into a freezing cold lake.

“You want to know how to rip the child out of a child? Fuck him. Fuck him repeatedly. Hit him. Hold him down and shove things inside him. Tell him things about himself that can only be true in the youngest of minds before logic and reason are fully formed and they will take hold of him and become an integral, unquestioned part of his being.”

The book fell victim to an injunction preventing publication after Rhodes’s ex-wife insisted that the account of his father’s abuse would be emotionally damaging to their son.

In overturning the injunction, presiding judge Lord Toulson noted: “There is every justification for the publication. A person who has suffered in the way the appellant has suffered, and has struggled to cope with the consequences of his suffering in the way that he has struggled, has the right to tell the world about it. And there is the corresponding public interest in others being able to listen to his life story in all its searing detail.”

The reaction to the news was overwhelmingly one of relief: both for the author but seemingly others too. Stephen Fry tweeted that he was “stupidly teary” about the judgment, which he saw as a vindication for Rhodes.

Vindication seems an odd concept to summon, as no-one seemed to be questioning the veracity of Rhodes’s story. But I think I understand what Fry means.

Rhodes’s case goes beyond the usual reasons we give for reporting child abuse: that it may help others to come forward, or that it may help snare past and future perpretators. While these are valid reasons, they are not the thing in itself. As the judge pointed out, Rhodes has a right to tell his own story and the denial of that right is a further abuse of a man who has already suffered. To deny the story is to inflict further harm.

In the Ten Stages of Genocide, developed by Gregrory Stanton of Genocide Watch (and explored in a new play, No Feedback, opening this week in London), denial is listed not as the aftermath of genocide, but as an intrinsic part of it.

“Denial is the final stage that lasts throughout and always follows a genocide. It is among the surest indicators of further genocidal massacres. The perpetrators of genocide dig up the mass graves, burn the bodies, try to cover up the evidence and intimidate the witnesses. They deny that they committed any crimes, and often blame what happened on the victims. They block investigations of the crimes…”

Thus insult goes hand in hand with injury. This is far beyond the idea of free speech, of the ability to bear witness, as a utilitarian idea: the right to speak is essential, like the right to eat. Denied communication of our experience, we, creatures who rely on social interaction, are starved (Forché describes “the social”, the place where one bears witness, as “a place of resistance and struggle, where books are published, poems read, and protest disseminated. It is the sphere in which claims against the political order are made in the name of justice.”)

The effect of denial imposed on individuals and societies can be seen everywhere from Rhodes continued anguish to Armenia’s entry in this year’s Eurovision Song Contest, it’s title Don’t Deny a pointed reminder on the centenary of that nation’s still-disputed trauma.

Sometimes, in free expression arguments, people will argue not that there is a right to speak, but no right to be listened to: this may be true, but there is a visceral need to be heard, to have our stories acknowledged. For it is our stories that make us. In that sense, the publication of James Rhodes’s memoir, after the attempts to deny him his chance to tell his tale, marks his vindication not as a pianist or a writer, but as a human being.

This column was posted on 21 May 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

20 May 2015 | Campaigns, mobile, Press Releases, Statements

A UK Supreme Court judgment today has overturned an injunction preventing publication of the musician James Rhodes’ memoir Instrumental.

The case known as OPO v MLA was brought by Rhodes’s ex-wife, who claimed that publication of the book would cause psychological harm to their son, who suffers from Asperger’s syndrome, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, dyspraxia and dysgraphia. The memoir, to be published by Canongate, is an account of James Rhodes’s traumatic childhood in which he was the victim of sexual abuse and its impact on his adult life. He recounts the vital role of music and how it saved him from self-harm, addiction and suicide.

The High Court struck out the proceedings, arguing that there was no precedent for an order preventing a person from publishing their life story for fear of its causing psychiatric harm to a vulnerable person. But a temporary injunction was granted by the Court of Appeal until the case came to trial, on the grounds of an obscure Victorian case Wilkinson v Downton, in which a man who played a practical joke on the wife of a pub landlord was found to be guilty of the intentional infliction of mental distress.

English PEN, Index on Censorship and Article 19 intervened in the appeal at the Supreme Court as third parties, arguing that the Court of Appeal’s decision would have a chilling effect on the production and publication of serious works of public interest and concern.

In a robust defence of freedom of expression, the court ruled: ‘The only proper conclusion is that there is every justification for the publication. A person who has suffered in the way that the appellant has suffered, and has struggled to cope with the consequences of his suffering in the way that he has struggled, has the right to tell the world about it.’

The Supreme Court criticised the Court of Appeal’s ruling in its judgment, stating that the terms of the injunction were flawed and voicing its concern about the curtailment of freedom of speech:

‘Freedom to report the truth is a basic right to which the law gives a very high level of protection. It is difficult to envisage any circumstances in which speech which is not deceptive, threatening or possibly abusive, could give rise to liability in tort for wilful infringement of another’s right to personal safety. The right to report the truth is justification in itself. That is not to say that the right of disclosure is absolute, for a person may owe a duty to treat information as private or confidential. But there is no general law prohibiting the publication of facts which will cause distress to another, even if that is the person’s intention.’

‘This an important judgment overturning an injunction that not only prevented the public from reading a powerful book of wide interest, but posed a significant threat to freedom of expression more broadly. It’s encouraging to see the Supreme Court’s clear and unequivocal support for free speech,’ said Jo Glanville, Director, English PEN.

‘The decision of the Supreme Court is an important verdict for free expression. In particular we commend the court’s recognition that freedom to report the truth is a basic right protected in law and its reassertion of the right to produce material that others may find offensive,’ said Jodie Ginsberg, CEO, Index on Censorship.

Last October, 20 leading writers, including David Hare, Michael Frayn, William Boyd and Tom Stoppard wrote to the Daily Telegraph to say that they were ‘gravely concerned about the impact of this judgment on the freedom to read and write in Britain’.

They added: ‘The public is being denied the opportunity of reading an enlightening memoir, while publishers, authors and journalists may face censorship on similar grounds in the future.’