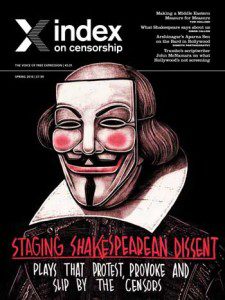

How Shakespeare’s plays smuggle in protest

Spring 2016 cover

Index on Censorship magazine editor Rachael Jolley introduces our Shakespeare special issue, which, as the 400th anniversary of his death approaches, explores how his plays have been used to circumvent censorship and tackle difficult issues around the world, from Bollywood adaptions to Othello in apartheid-era South Africa and a ground-breaking recent performance of Romeo and Juliet between Kosovan and Serbian theatres

Theatre, in whatever form it takes, tells us something about society. Sometimes the stories are uncomfortable, but they need to be explored.

Telling stories that challenge societal realities requires performers to negotiate their way around obstacles. In authoritarian countries performing works of “established” or “historic” playwrights can give actors the chance to tackle significant themes that would otherwise never be allowed.

Poet Robert Frost said writing free verse was like playing tennis with the net down. But where nets are still up, performances of Chekhov, Shakespeare, and Cicero may squeeze over a few shots, where a new and unknown writer’s work would face far more rigorous opposition from the authorities. On the occasion of the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death, in this issue we take a look at the words of the son of Stratford and why they are still performed around the world.

One of theatre’s challenges is that it must continue to make sense to all audiences, the young, the old and everyone in between. Shakespeare’s plays can be ballsy, straightforward and about the ordinary. This is no doubt why his words have had influence for so long, while other playwrights have been forgotten.

This appeal, and relevance, remains a challenge for writers and directors. After university, I worked for a few months in the legendary Hull Truck theatre in the north-east of England, led by artistic director and playwright John Godber. What Godber did in a working-class city where few people would think, “Hey, let’s go see a play tonight”, was to write and stage plays that sounded like they were about normal people and normal things.

The most famous, Bouncers, is about the people who do door security in nightclubs. A tale of ordinary life, it was funny, and lots of people came to see it in the little theatre in the untarted-up bit of Hull, around the corner from where millions of milk floats loaded up. And people who didn’t normally go to the theatre thought it was alright for them and told their families and their friends it was a laugh, and so more and more of them came to see more Godber plays. I re-read Bouncers a month ago, and I realised (I guess, I had forgotten), it was more than just funny. There’s real stuff in there about how people live and what they dream and how they find a compromise with life, and what needs to change. Hard stuff. Important stuff. Social comment. Hidden in there among the jokes.

That’s how theatre informs us of lives beyond our own. And that’s why, sometimes, governments fear it. And that’s why in another place, and under another type of government, a play like Bouncers might slip its social messages by those hard-line censors who might not think it’s about anything but some fat bald guys who work on the door at a dodgy nightclub having a chat.

But the other role of stories, plays and art is that they also have the power to goad, protest and say stuff that normally can’t be said. Sometimes stories make what had been outrageous or out-of-the-ordinary feel more acceptable. Sometimes fiction can go places where newspapers can’t, but still deal with the real.

Arthur Miller’s 1952 play The Crucible used the Salem Witch Trials to take a poke at the power of accusation and public panic happening in McCarthyite trials, with their accusations of “communism” which left thousands of people blacklisted and unemployed. People from postmen to Hollywood producers were called to give evidence to the House of Un-American Activities Committee, which aimed to “out” those with left wing or pro-Communist views as dangerous. Despite the horrifically charged climate of the “reds under the bed” era, which meant former stars such as Charlie Chaplin and Orson Welles were forced into exile, Miller was still able to get his play produced. It remains a classic, still relevant after all these years.

The similarities between Salem and the McCarthy trials were obvious to those that thought about it. But sometimes those who are appointed as censors are not the thinking types. So ideas slip by them. And that can be useful.

Shakespeare, of course, has plenty of controversy, inspiration and power within his plays. It’s just less obvious to those who aren’t paying attention. There’s nothing mousy and out-of-date about the speech of roaring rhetoric of Henry V to his rag-taggle followers, to raise spirits and to go forth against a much larger army: “We few, we happy few, we band of brothers, for he today that sheds his blood with me shall be my brother.”

Henry V’s speech could still be used to rally the troops. They still feel pointed, and relevant. Yet because Shakespeare is Shakespeare, his words and ideas escape the red pen of the brutal censor more than others do. “Centuries out of date”, the censors and government red-penners must think. “Can’t do any harm.”

So in some countries, Zimbabwe among them, Shakespeare is used to smuggle ideas of protest past those who veto that kind of thing. Playwright Elizabeth Zaza Muchemwa says in her country, where there are so many restrictions on theatre companies, Shakespeare appears to slip through the net, raising storylines of senility of a king (King Lear) and of overthrowing of a leader (Julius Caesar), which feel important to Zimbabwean citizens dealing with the long last days of an elderly ruler. Shakespeare’s writing continues to inspire, she says, in her piece.

But the badge of Shakespeare doesn’t always mean productions will escape the long reach of the law. In 1981, a Turkish production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream came to the stage as a military government stepped up its power. As Index’s Turkey editor Kaya Genç outlines in the magazine any public event, newspaper article, poem or artistic production carrying even the slightest trace of dissent against the military authority was certain to be punished. This production was felt to have highlighted the relationship between the elite and the rest (the rude mechanicals) and how status was used for power. Eight members of the cast ended up shaven-headed in prison in the next few months. The play did not squeeze by. It was noticed.

Leading Turkish theatre director Kemal Aydoğan, who produced the latest version of the play in Turkey, tells Index magazine that the Dream has a strong relevance to troubles in his nation today. He sees a parallel between the struggle between desire and the law, and the dream of the forest, a place where desire and equality dominates.

Don’t miss another gem in the latest magazine, Jan Fox’s long-form essay on the love/hate relationship the USA has, and has had, with Shakespeare (page 12). The Puritan founders felt all theatre was beyond the pale, and looked frowningly on its ribaldry. So this is a nation with a core of censorship at odds with its commitment to its First Amendment freedom of expression. LA-based Fox covers why Shakespeare still upsets parents because of its drama around everything from teenage suicide to under-age sex. “Shakespeare is telling us about our secret self and that’s what people are afraid of,” Gail Kern Paster, editor of the US-based journal Shakespeare Quarterly tells Fox.

While plays by established writers can smuggle through dissent and protest in countries with strict reins of performance exist, as nations move towards greater democracy then the public must expect and demand far more provocative, outrageous and openly challenging material from its theatre as well as welcoming the established gems. We should all look forward to the signs of those times.

Order your full-colour print copy of our Shakespeare magazine special here, or take out a digital subscription from anywhere in the world via Exact Editions (just £18* for the year). Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship fight for free expression worldwide.

*Will be charged at local exchange rate outside the UK.

Magazines are also on sale in bookshops, including at the BFI and MagCulture in London as well as on Amazon and iTunes. MagCulture will ship to anywhere in the world.

Related:

Award-winning cartoonist discusses his design of the latest Index on Censorship magazine cover

Table of contents

Subscriptions