16 Sep 2016 | Magazine, Volume 45.03 Autumn 2016

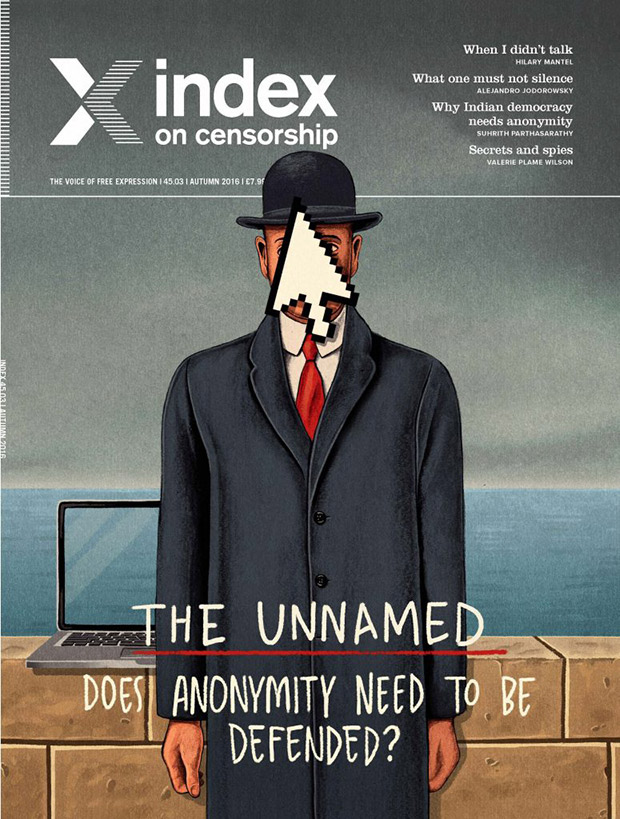

Autumn’s anonymity cover by Ben Jennings

The forthcoming issue of Index on Censorship magazine explores anonymity through a range of in-depth features, interviews and illustrations from around the world. The special report looks at the pros and cons of masking identities from the perspective of a variety of players, from online trolls to intelligence agencies, whistleblowers, activists, artists, journalists, bloggers and fixers. Contributors include former CIA agent Valerie Plame Wilson, journalist John Lloyd, Bangladeshi blogger Ananya Azad and philosopher Julian Baggini,

Outside of the themed report, this issue also has a thoughtful essay by novelist Hilary Mantel, called Blot, Erase, Delete, illustrated by Molly Crabapple. Andrey Arkhangelsky looks back at the last 10 years of Russian journalism. Uzbek writer Hamid Ismailov explores how metaphor has taken over post-Soviet literature and prevented it tackling reality head-on. There is also poetry from Chilean-French director Alejandro Jodorowsky and Russian writer Maria Stepanova, plus new fiction from Turkey and Egypt, via Kaya Genç and Basma Abdel Aziz.

You can pre-order your copy here, or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions. Copies will be available at the BFI, the Serpentine Gallery, MagCulture, (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester), Carlton Books (Glasgow) and on Amazon. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship continue its fight for free expression worldwide.

Index on Censorship magazine was started in 1972 and remains the only global magazine dedicated to free expression. Past contributors include Samuel Beckett, Gabriel García Marquéz, Nadine Gordimer, Arthur Miller, Salman Rushdie, Margaret Atwood, and many more.

16 Sep 2016 | Africa, Eritrea, News and features

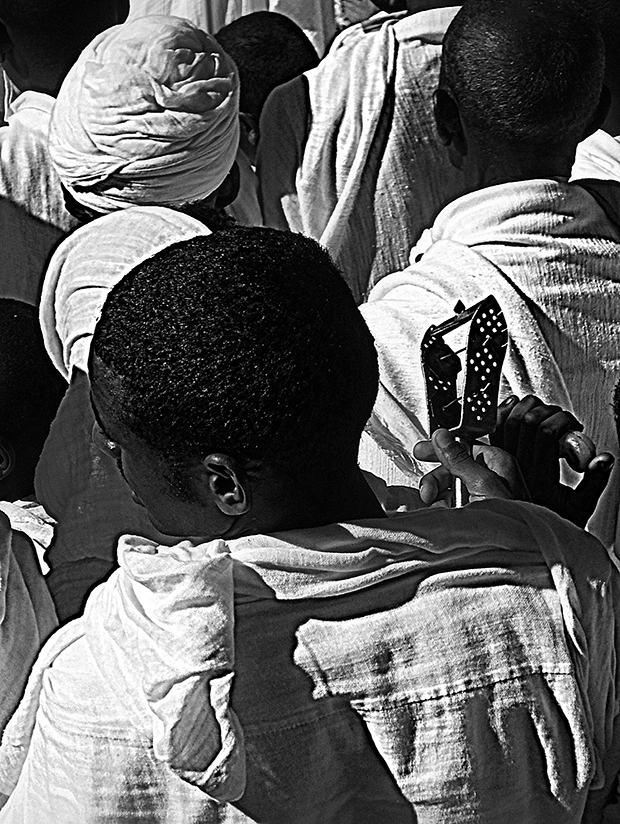

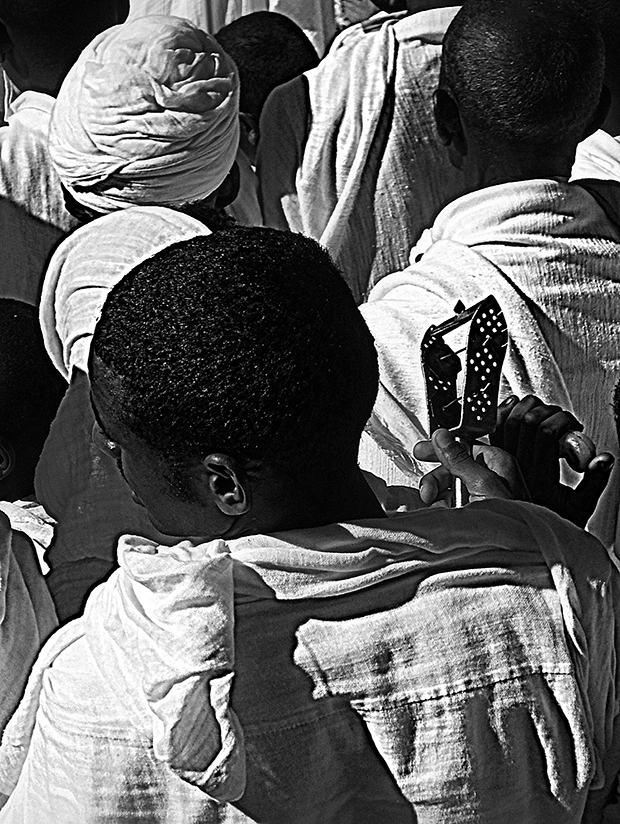

Scenes from Eritrea, photographs by Yonatan Tewelde

It initially sounded like a joke; gradually it got serious and then tragic. A decade and a half later, it is catastrophe.

Fifteen years ago on 18 September, 2001, fellow students of University of Asmara and I were confined in two labour camps, GelAlo and Wi’A, for defying a requirement of unpaid summer work. We were kept in the camps, under harsh, atrocious living conditions and open to the weather that normally reaches 45 C (113 F) for about five weeks. As we were preparing to return home, we learned the government had banned seven private newspapers and imprisoned 11 top government officials.

The day after our homecoming, beaten down and demoralised, I went to meet Amanuel Asrat, chief editor of Zemen newspaper. About 10 days before that, he had received an article, in which I detailed our living conditions, that I had managed to get smuggled out of the prison camp. My piece was published in the last issue of the newspaper.

An atmosphere of fear pervaded Asmara. The environment had changed abruptly from heated and loud political debates to people resigning themselves to whispers and silence.

Unlike our previous meetings when Asrat greeted me with a joke, this time his dejection was obvious.

I do not remember exactly what we talked about, nor do I remember where we met. I assume Asrat must have expressed satisfaction about my safe return (as two students had died in the camp) and perhaps asked about my family. It’s possible we talked about the days before we had been sent to the prison camp. I do not know.

Yet, I remember vividly that we briefly talked about the letter I had sent him from the camp, and him explaining why he had published it anonymously. He didn’t want to incriminate me in its publication. Asrat also assured me that he had destroyed the original letter after publishing it.

What else do I remember from that encounter? Nothing substantial apart from him saying in a resigned tone, “Things are getting worse. It is inevitable we [the journalists] will also follow the political leaders [who had been imprisoned].”

At that point, we went our separate ways, probably hoping to meet some days later.

Before a second meeting with Asrat, I received the news of his and other journalists’ arrests. Even then, no one thought they would be held for more than a few days or weeks.

This is why journalist Dawit Habtemichael showed up at his workplace the next morning — even after security had come to his home the previous day and hadn’t found him. He reasoned that they would arrest him and release him shortly thereafter, a common occurrence at the time. He arrived confidently at his office, prepared to be arrested. He probably felt that fleeing would be an act of betrayal to his colleagues and friends.

Contrary to expectations, both Habtemichael and Asrat have been kept incommunicado in secret prisons with 10 other journalists and 23 political figures for the last 15 years. The Eritrean authorities have never clarified their fates, but some allegedly leaked information by an anonymous whistleblower indicates that only 15 of the total 35 prisoners are alive in the worst living conditions. The journalists who were incarcerated in connection with the press crackdown in 2001 are: Amanuel Asrat, Idris Said Aba’Are, Seyoum Tsehaye, Yousif Mohammed Ali, Said Abdelkadir, Medhanie Haile, Dawit Isaak, Dawit Habtemichael, Matheos Habteab, Fessaha “Joshua” Yohannes, Temesegen Ghebereyesus, and Sahle “Wedi-Itay” Tsegazeab. The leaked source allegedly states only five of the 12 were alive in deteriorating health conditions as of the beginning of this year.

So until the arrested journalists were transferred to an unknown prison outside the capital, many of us – and maybe even those who had been arrested – had high hopes that things would normalise and they would shortly be released from detention. Apart from the architects of repression, nobody guessed that the reign of terror and fear would last for 15 years – and continue to this day.

The culture of fear and hushed whispers gradually pervaded Eritrea until it became the nation’s signature reality. All roads began leading to dead ends. Silence and lack of cooperation became the only means of defiance that would not lead to arrest and imprisonment. The regime’s elimination of all independent media operating in the country conspired with a lack of public forums to effectively zombify Eritreans living inside the country.

Now it has reached a stage where failure to applaud unconditionally all actions taken by the government, no matter how irrational or arbitrary, can be considered as dissidence.

Over the last 15 years Eritreans have been pushed to the edge. Fear has been internalised. Nationals living inside the country are beaten down to docility and respond to orders and requirements without question. The country is plagued with harsh living conditions as a result of shortsighted policies, tattered institutions and a ragged social fabric characterised by mistrust.

Unlike 2001 when I was confident that the journalists would be released after a short time, in January 2015, I celebrated as miraculous the release of Radio Bana journalists after six years in prison without charges. Of course, I had no doubt they were all innocent, and the release of an earlier batch two years before confirmed this fact. Among them was a man who had been imprisoned for four years in place of another man who shared the same first name. In another nonsensical interrogation, related by one of the Radio Bana journalists who were released, authorities showed a print article as evidence of a broadcast allegedly aired by the opposition radio station.

No matter how long the Radio Bana journalists had stayed in prison or the sufferings they had gone through, their release was still big news to celebrate. Any release of political prisoners has been a rare occurrence in Eritrea, which is why many of us called the freed journalists to congratulate them. In a system that follows the perverted logic of “guilty until proven innocent,” it was important to celebrate their freedom because no one can guess the irrational acts the regime repeatedly takes.

With the state media parroting ceaseless propaganda and hate-filled editorials, citizens have mastered a special skill: how to read between the lines. Most Eritreans do not listen to what the president says in his regular, repetitious interviews with the national media. Rather they read his gestures, listen to his tone and scan his appearance to get a feel for the state of the country. Many Eritreans check the media just long enough to determine whether he looks healthy or not.

This accumulation of fear, with a stifled media and ubiquitous censorship, has earned Eritrea the title of “most censored country in the world”, according to Committee to Protect Journalists. It also has placed it as the last country in World Press Freedom Index, as reported by Reporters Without Borders.

More about Eritrea

Letter: Eritrea must free imprisoned journalists

Escape from Eritrea: Ismail Einashe

Scenes from Eritrea, photographs by Yonatan Tewelde

Yonatan Tewelde is an Eritrean photographer and filmmaker who is also working as PEN Eritrea in Exile’s webmaster and graphic designer

16 Sep 2016 | Bosnia, Europe and Central Asia, Greece, Italy, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, Netherlands, News and features, Serbia

Each week, Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project verifies threats, violations and limitations faced by the media throughout the European Union and neighbouring countries. Here are five recent reports that give us cause for concern.

Members of the Greek far-right Golden Dawn party assaulted a journalist at a protest against the presence of a refugee detention centre on the island of Chios on 14 September.

Editor-in-chief of Astrapari.gr, Ioannis Stevis, was covering the events at the entrance of the camp when a local representative of Golden Dawn, Mattheos Mermigousis, assaulted him and threw his camera on the ground where it broke.

Greek riot police were close by when the assault happened but refused to arrest Mermigkousi despite his request. Stevis has pressed charges against local Golden Dawn representatives.

Ismar Imamovic, an editor at local broadcaster RTV Visoko, was assaulted by a masked individual after he left the TV station on 14 September.

The incident occurred shortly after midnight. As Imamovic told Patria, a few seconds after he had left the building a masked man attacked him from behind. “First he struck me down and then beat me brutally,” Imamovic said.

The incident was reported to the police but so far there is no information regarding the culprits’ identity. Political parties have condemned the attack.

A Dutch-Turkish journalist for the Turkish pro-government newspaper Sabah was arrested in the city of Zaandam while reporting on a police operation on 12 September.

Fatih Ozyar was filming a police raid in an area of Zaandam when he was asked by the police to leave. He told the police that he was a journalist but was arrested with eight other people.

“I was treated roughly by four police officers and brought to a police cell where I was left for 15 hours,” he said. Ozyar was released the following day with a fine for not following police instructions.

The municipality of Amatrice announced on 12 September it plans to sue Charlie Hebdo magazine for a cartoon published about the 24 August earthquake that killed 295 people, Le Figaro reported.

The Amatrice municipal officials announced they were suing for libel.

“This is an unbelievable and senseless macabre insult made to victims of a natural disaster,” the municipality’s lawyer said.

Nedim Sejdinovic, the president of the Independent Journalist Association of Vojvodina, received death threats and threats of violence via Facebook on 12 September.

The threats came after Sejdinovic participated in a roundtable discussion about challenges in modern day Serbia. He compared Serbia in the 90s with the IS today. He also said that he believed Serbia’s ruling party was deeply corrupt and had destroyed society.

The Independent Association of Journalists in Serbia condemned the threats and urged a special prosecutor for cyber crime to identify those who are responsible.

16 Sep 2016 | mobile, News and features, Tim Hetherington Fellowship, United Kingdom

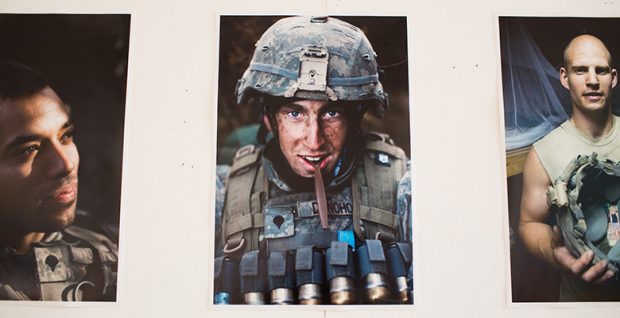

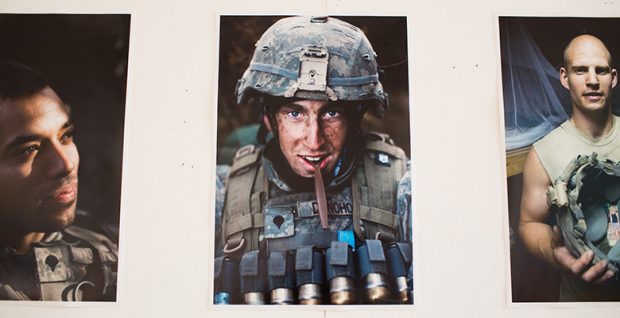

Photo: Liverpool John Moores University

Liverpool John Moores University officially opened its Infidel exhibition, a display of photographs by Tim Hetherington, on Wednesday night. The Liverpool-born photojournalist, who died in Libya under mortar fire in 2011, took the photos during the year he spent embedded with the US Army in Afghanistan’s Korangal Valley while shooting his 2010 Oscar-nominated documentary Restrepo.

Stephen Mayes, a personal friend of Hetherington’s and the director of the Tim Hetherington Trust, spoke at the launch, and highlighted three moments from Hetherington’s short film Diary, which he felt summed up the photographer’s feelings about dividing his time between west London and west Africa. Mayes also recalled a conversation he had with Hetherington around a month before his death, about how photography is great at portraying the “hardware” of war – the guns, the bombs, the carnage – but that Hetherington preferred to work with what he called the “software”, the young men who fight and the people caught in the middle.

The photographs in the Infidel exhibit are a perfect example of what was so impressive about Hetherington’s work. Despite having weathered a year of almost constant combat alongside a platoon of US soldiers, he took striking images that stepped back from the front line. His portraits featured men hugging, relaxing and playing games, highlighting their individual humanity and vulnerability in an environment that treats them as means to an end.

As the new recipient of the Tim Hetherington Fellowship, the result of Index on Censorship’s collaboration with the trust and LJMU (where I graduated in journalism), I’m inspired by the spirit of that work. I’m struck by the bravery and moral fortitude of a man who frequently put himself in harm’s way out of a sense of duty to the people around him. His determination to immerse himself in the lives of his subjects and portray the emotional truth of their experience has reminded me why I always wanted to be a journalist. Journalism is about letting people tell their stories.

Index on Censorship fights for the rights of people to be heard. Hetherington spent his life trying to tell untold stories. It’s an honour to be part of his legacy.

Infidel is open now at the John Lennon Art and Design Building, Duckinfield Street, Liverpool until Friday September 23. Admission is free, 10am to 5pm, Monday to Friday.