[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Back Row from left: Adam Rajab, Malak Rajab and Nabeel Rajab. Front Row from left: Sumaya Rajab and Zainab Alkhawaja. (Photo: Adam Rajab)

Human rights defenders often confront obstacles that make their work difficult. This is especially true in Bahrain, where the Sunni monarchy and government have been bent on silencing all opposition ever since the Arab Spring when tens of thousands of Bahraini citizens protested for democratic reform.

In recent months, the nation’s only independent news outlet, Al Wasat, was shuttered and prominent human rights activist Nabeel Rajab was sentenced to two years in prison for “spreading fake news”.

The families of activists suffer along with their loved ones and are often targeted with official harassment: detention, loss of employment, beatings and harassment. Each case is an individual story of a struggle for freedom.

A result of actions

Members of Sayed Ahmed Alwadaei’s family have been harassed and detained due to his ongoing campaigning for democracy and human rights in Bahrain. Most recently his mother-in-law and brother-in-law were detained while Alwadaei attended the United Nations Human Rights Council in March.

Alwadaei, director of advocacy at the Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy, is no stranger to detention: he was arrested twice in 2011 and served a six-month sentence in a Bahraini jail. He found asylum in the UK in July 2012. In February 2015, Alwadaei was among 72 Bahraini citizens to be stripped of their citizenship.

Sayed Ahmed Alwadaei with his son Yousif (Photo: Moosa Satrawi)

In October 2016, Alwadaei’s wife and infant son Yousif also faced official harassment as they tried to leave Bahrain to join Alwadaei in the UK. His wife was arrested at the airport and held overnight, during which time she was ill-treated. It was not until a few months later that she and her son were able to leave the country.

Other members Alwadaei’s family, including his sister, have also faced interrogations.

When asked how he continues campaigning under these circumstances, Alwadaei told index: “We can only get through this by sticking together and staying strong. It’s important to have a supportive family. The potential for arrest and torture is something they know and have to be willing to sacrifice.”

He added that he is balancing his efforts to get his mother-in-law out of prison while continuing his work in activism. “It’s hard but this is the right thing to do.”

“The oppression or torture aims to do one thing: to break your will because you’re not ready for the consequences,” Alwadaei said. “This is the state they want to leave you in. They want you to be broken and this is why we keep going.”

A life-long struggle

Maryam Al-Khawaja has been preparing for and participating in the struggle for human rights her entire life.

As a young child growing up in Denmark, she and her three sisters attended an English-speaking school, but the Al-Khawaja family knew they were only in the country temporarily. Her mother and father had been exiled for speaking out in Bahrain.

At a very young age, she remembers her parents asking her and her siblings before bed: “What have you done today to make the world a better place?” She told Index that her father wouldn’t help them answer the question because he wanted them to think about how the world could be. She remembers dinner conversations alive with politics and philosophical discussion about whether having false hope or no hope was better.

Around the 7th or 8th grade, Al-Khawaja knew wanted to be like her father when she grew up; she wanted to be an activist.

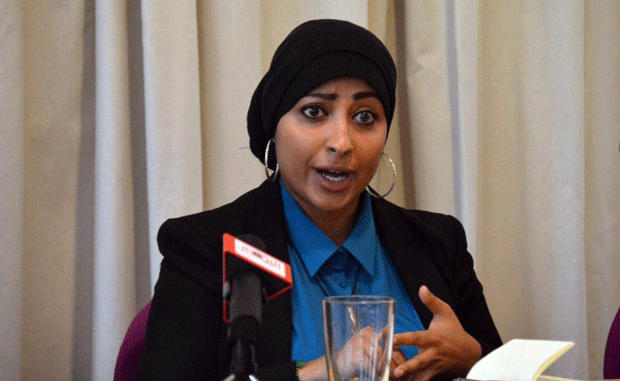

Maryam Al-Khawaja (Photo: David Coscia for Index on Censorship)

Al-Khawaja was 14 when her family returned to Bahrain in 2001. She recalls thinking her family was ready to take on the challenges and that the people of Bahrain would be ready to fight with them. But that was not the case. The country was tired of conflict and believed that the king’s promised reforms would be implemented. At the same time, activists were not popular among ordinary Bahrainis.

At college she said she was criticised by her classmates for speaking her mind about the state of their country, which caused her to lose interest in her father’s reform work. At the time, she asked him: “Why are you trying to change a situation for people who don’t want to change it for themselves?” His response was simple: “Someday you will understand.”

It wasn’t until 2011 during the Arab Spring protests that she developed a newfound respect for her father and was ashamed of herself for ever doubting him. She admits growing up in Denmark made her think fighting for human rights would be easy. When her father, along with 12 other leaders of the uprising, was arrested and sentenced to life imprisonment, she found that a life of campaigning isn’t so effortless.

During our conversation, Al-Khawaja jumped off the phone for a few minutes to take a call from her father. She had not heard from him in over three weeks and said their phone calls are always random and typically short as it is normal for the line to be cut if anything about the Bahrain government or any activist’s work is mentioned.

Until recently, her mother and sisters in Bahrain had not seen her father since February as their requests to visit have continually been denied. Al-Khawaja has not seen her father since 2014 as there are multiple fabricated charges against her that would mean imprisonment if she returned to the country.

Since her father’s imprisonment, Al-Khawaja and her older sister Zainab have been active in the push for human rights and freedom of speech in Bahrain. She says her father has two main characteristics as an activist: a fierce advocate and a fiery speaker. She explained that she and Zainab are the two parts to that whole: Al-Khawaja as the advocate and Zainab as the speaker.

Al-Khawaja said the work of her father and her sister Zainab has been tough for her two younger sisters. One sister had the highest scores in nursing school in Bahrain and graduation seemed to promise a job. But the paperwork from the government granting her access to work never came. She’s been waiting nearly eight years without a job. Al-Khawaja said it’s difficult for her family members when they’re in jail as they have to “take care of us when we cannot take care of ourselves”.

Her mother also felt the effects of the family member’s work when she was fired from her private school teaching job where she was the head of guidance.

A cause for celebrity status never wanted

Adam Rajab realised when he was young that his father Nabeel wasn’t like other dads. “I was so confused ‘why does my father work all day, while other fathers have certain working hours?,’” he told Index.

During a holiday he asked his father to take a break for a day. His father answered: “My colleagues are in prison. I can’t stop my work because they are suffering behind bars.”

In 2006, when Rajab was nine years old, he vividly recalls seeing his father come home bleeding from his head with a swollen and bruised back. “I was shocked and terrified but my father continued protesting like nothing had happened,” he said. “This was terrifying to me but the determination and fearlessness I saw in him really inspired me.”

In 2011 Nabeel Rajab’s work became well known. He appeared on TV and was the first activist to use social media to support the revolution then sweeping Bahrain. “Wherever we went, people would stop him and start taking pictures,” Adam said, adding that the strange situation was a shock to the family. “It started to become difficult because we couldn’t enjoy a private life like we used to.”

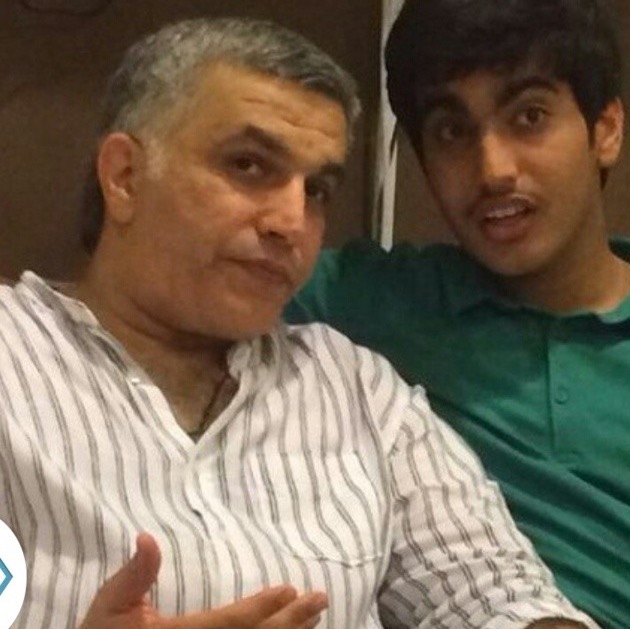

Nabeel Rajab with his son Adam Rajab

As a leader of the movement, Rajab’s father has become a face leaders around the world recognise but do little about. For years he has been in and out of jail. On 10 July 2017 he was sentenced to two years in prison for “broadcasting fake news”.

Although no one in the family has been arrested, his mother was harassed at her government job and then fired. Rajab and his sister have also faced harassment in school.

Rajab and his father have a very close relationship so the imprisonment has not been easy. “I haven’t seen him for more than a year now and he faces more charges which probably means more prison sentences,” Rajab said. “I find it difficult to enjoy anything while he is locked up in a cell and deprived of life, but as he taught me, the spirit is always up.”

Rajab wants his father to free and for them to live like any other ordinary family, but this does not take away from how proud he is or the strength of his belief in his father’s cause.

An open ended sentence

It’s difficult to imagine the emotions these activists and their families go through on a daily basis. A psychologist from the Refer Self Counselling Psychology Practice explained to Index that having a family member with a sentence with a sure release date is one case but when trials or release dates are postponed time and time again as they are in Bahrain, it is much more difficult. “We are rational problem solvers but not good with the unpredictable.”

The psychologist explained the situation in Bahrain is unlike what most with family members behind bars will ever experience. False hope puts an even greater emotional strain on loved ones.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1503052292764-bb1a6c59-5e91-2″][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]