19 Apr 2017 | Awards, Awards Update, News and features, Youth Board

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Since winning the Freemuse Award for Music in 2010, Mahsa Vahdat has continued to use her music to fight for freedom of expression for the women of Iran. Since the Iranian revolution in 1979, female solo vocalists are permitted to perform only for female audiences; they cannot perform for men except when part of a chorus as conservative clerics say women’s voices have the power to trigger immorality and arousal.

But Vahdat learned music as a child and went on to study it at university in Tehran. She was encouraged to perform there despite the strict new rules of the Islamic Revolution. Not only does she sing but she also plays the piano and the setar, a Persian string instrument that’s a member of the lute family. Now she has taken that freedom to the Iranian diaspora and world music circles across the globe, performing at international venues where her voice is not discriminated against on the basis of her gender. She refers back to the classical Iranian poets – Rumi, Khayyam and Hafez – as well as using contemporary poetry.

Vahdat’s commitment to fight for her right to sing often meets obstacles; in 2011 she gave a concert at the residence of the Italian embassy in Tehran despite the attempts of the government security forces to stop guests from entering the building. But she has built a following around the world, especially in Norway after touring schools there and presenting a positive, musical image of Iran. In 2011 she released the album Twinklings of Hope with her sister to critical acclaim and has gone on to collaborate with other performers such as Mighty Sam McClain.

Despite the conservatism of her homeland she still teaches Persian singing in Tehran, ensuring that the tradition of both folk music and that of the female artist stays alive. She continues to be an ambassador for the Freemuse Organization which advocates freedom of expression for musicians and composers across the world.

Sophia Smith-Galer is a member of Index on Censorship’s Youth Advisory Board. She is an MA student studying Broadcast Journalism at City University in London. She studied Spanish and Arabic previously at Durham University.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”85476″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2016/11/awards-2017/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards

Seventeen years of celebrating the courage and creativity of some of the world’s greatest journalists, artists, campaigners and digital activists

2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1492506354793-87f74769-0713-9″ taxonomies=”2562, 7359″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

19 Apr 2017 | Awards, Awards Update, News and features, Youth Board

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

“An epic yet intimate work that deserves to be recognised and to endure as the great Tiananmen novel.” The Financial Times’ review on Ma Jian’s 2008 novel The Beijing Coma was rather positive, and it was not alone. The book, which explores both the contemporary China and the well-known protests on Tiananmen Square in 1989, was also nominated for the Man Booker Prize and in 2009 it received Index on Censorship’s TR Fyvel Book Award. The Chinese Government banned the book, and Ma himself often criticised the government for trying to erase all memory of the thousands of innocent lives lost during the Tiananmen massacre.

Although his works were banned in China, Ma – who is today a British citizen – had been able to return to the country regularly, until 2011, when he was prevented from crossing the border from Hong Kong to the mainland. He was given no reason for the ban, nor any implications of how long it would last. Although his movements were also closely monitored on his previous trips to China, after the ban he said to The Guardian: “The fact that I have been denied entry is an indication of how repressive the regime has become. It is vitally important for me, both personally and for my writing, to be able to return to China freely, so being barred entry has caused me deep concern and distress.”

In spite of the ban, Ma kept on writing about China, and in 2013 he published the novel The Dark Road. In this he explores the costs of China’s one-child policy through the lens of a poor family living in China’s lesser mentioned rural hinterland. According to the New York Times: “In The Dark Road, as in Beijing Coma, Mr. Ma is adept at jolting our senses, transporting us, with a few words about a pain, a taste or an odour, to those parts of China, and millions of people, who exist on the far fringes of the economic miracle.”

Not only does he try to shed light on the lesser known problems in China in his work, Ma Jian often speaks about the country in his public appearances as well. In 2012 when China was selected to be the London Book Fair’s market focus he smeared red paint over his face to protest against China’s censorship policies. He accused the 180 invited Chinese publishers of being the “mouthpieces of the government”, and said: “In this book fair that looks so modern, so impressive, so beautiful, you will not see the ugly reality that lies behind … you will not hear the voices of the writers who are persecuted in China.”

Júlia Bakó is a member of Index on Censorship’s Youth Advisory Board. She is a Hungarian journalist, student and activist currently living in Budapest. After finishing her first degree in Journalism, she has started studying International Relations.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”85476″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2016/11/awards-2017/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards

Seventeen years of celebrating the courage and creativity of some of the world’s greatest journalists, artists, campaigners and digital activists

2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1492505976322-7a0f33e9-9799-9″ taxonomies=”529, 85″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

19 Apr 2017 | Index in the Press

Morning Brief: Politico Media reporter to head new initiative to track press freedom issues in the US — needed, it seems, in response to new president’s vocal disdain for the media. Read the full article

19 Apr 2017 | Awards, Awards Update, Digital Freedom, News and features, Youth Board

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

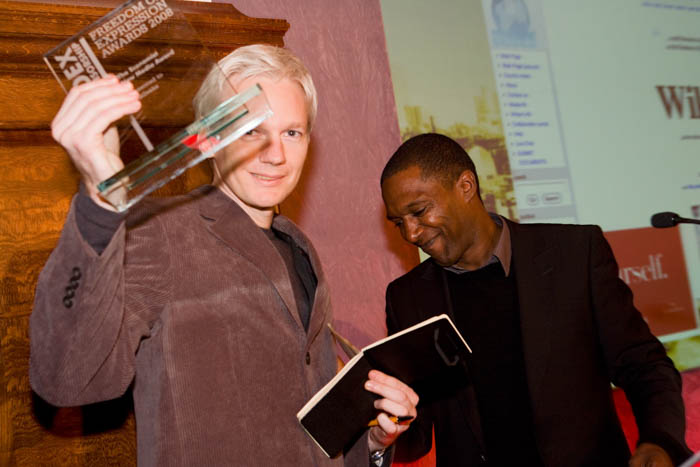

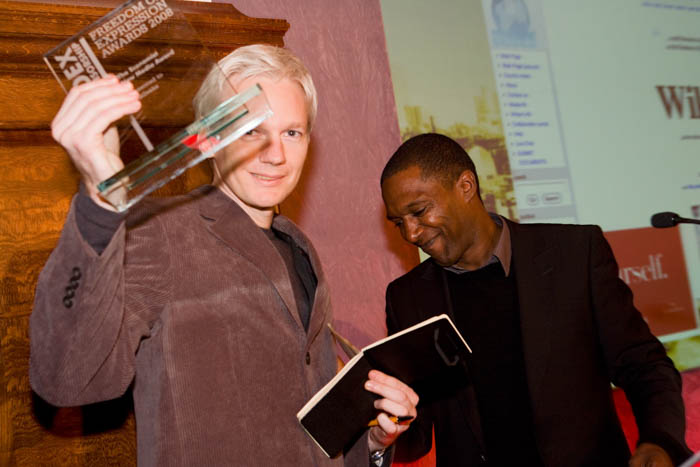

It has been over a decade since WikiLeaks released its cache of leaked documents and a little under a decade since it was awarded The Economist New Media Award at the 2008 Freedom of Expression Awards. In the following years, the non-profit organisation has published a considerable body of documents, holding to account states, corporations and individuals. Such actions would imply that it remains an apolitical organisation, whose mission is to ensure the defence of free speech and vitiation of censorship, although of late some would dispute its primary function. On the day of this year’s Dutch general election, WikiLeaks made separate Tweets with links to all documents referencing either Prime Minister Mark Rutte or right wing populist Geert Wilders.

Their fight for freedom of expression is often amorphous, which is well demonstrated by two publications from 2009. First, the March release of a website blacklist, proposed by Australia’s then communications minister, Stephen Conroy. Although it had been suggested by the Australian Government that the compulsory firewall would obstruct access to child pornography and sites related to terrorism, it was revealed to have included numerous websites which suggested a veiled political agenda. Second, the September release of an internal report on a toxic incident clean-up in the Ivory Coast by the oil trading company, Trafigura. That draft report was released after Trafigura obtained a super-injunction against The Guardian. Comparing the two, it is clear they share a commonality in combating instances of censorship, but beyond that an underlying characteristic in the material released is hard to find.

Where the organisation has had a focused, profound, and some would say not impartial, impact is on American politics. Three particularly notable moments were the 2010 Iraq and Afghanistan ‘War Logs’ and diplomatic cables associated with Chelsea Manning, the 2016 Democratic National Committee email leak, and the recent CIA Vault 7 release. It is perhaps the second of these that questions WikiLeaks’ apolitical position; in an interview with ITV, Julian Assange stated that he hoped the leaks would harm Hillary Clinton’s campaign. Certainly, the furore which surrounded Clinton’s use of a private email server in handling sensitive documents and the March 2016 release of her email archive was a boost for the Trump campaign. It remains to be seen whether the Trump administration or affiliated groups will be the subject of a WikiLeaks publication.

Whether one considers WikiLeaks a paragon, a zealot, or Machiavellian, it remains a powerful force against censorship. Although their profile has grown since being awarded The Economist New Media Award, they are still an organisation that appears wholly unconstrained by diplomatic pressures in holding bodies to account, who or whatever the target.

Samuel Rowe is a member of Index on Censorship’s Youth Advisory Board. He is currently a law conversion student at City, University of London, planning on practicing as a public law barrister with a focus in information law.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”85476″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2016/11/awards-2017/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards

Seventeen years of celebrating the courage and creativity of some of the world’s greatest journalists, artists, campaigners and digital activists

2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1492506268361-b3958523-724a-7″ taxonomies=”273, 8935″][/vc_column][/vc_row]