[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Authoritarian leaders know their history. They also know the history they would like you to know. They are aware, perhaps more than anyone else, that choosing images and stories from the past to align and amplify the ways a country is run can be a terribly powerful tool.

As Canadian historian Margaret MacMillan discussed with Index for this issue, dictators have been aware of the power of history to make their arguments for centuries. From the first Chinese emperors to today’s leaders – China’s Xi Jinping and Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdogan, among others – the selection of historical stories which reflect their view of the world is revealing.

“The thing about history is if people know only one version then it seems to validate the people in power,” said MacMillan.

But if you know more, you can use that information to make informed decisions about what worked in the past – and what didn’t – allowing people to learn and move on.

And right now, historical validation is an active part of the political playbook. In Russia, Vladimir Putin is a big fan of the tale of the great and powerful Russia. And what he doesn’t like are people who don’t sign up to his version of history.

Even asking questions about the past can provoke anger at the top. It interferes with the control, you see.

In 2014, Dozhd TV had an audience poll about whether Leningrad should have surrendered to the Nazis during World War II. Immediately there were complaints, as Index reported at the time. The station changed the wording of the question almost immediately, but within months various cable and satellite companies had dropped Dozhd from their schedules. Question and you shall be pushed out into the cold.

From the start, this magazine has covered how different countries have attempted to control the historical knowledge their citizens receive by limiting the pipeline (rewriting textbooks or taking history off the syllabus completely, for instance); using social pressure to make certain views taboo; and, in extreme cases, locking up historians or making them too afraid to teach the facts.

In our Winter 2015 issue, we covered the story of a Palestinian teacher who took his students to visit Nazi concentration camps in Poland because he felt they should know about the Holocaust. But not everyone agreed. While he was on the trip, there were demonstrations against him, his office was stormed and his car was torched. Later there were threats against his family. To escape the danger, he and his family had to move abroad. The teacher, Mohammed Dajani Daoudi, who wrote about his experiences for the magazine, said: “My duty as a teacher is to teach – to open new horizons for my students, to guide them out of the cave of misconceptions and see the facts, to break walls of silence, to demolish fences of taboos.”

What an incredibly brave vision for a teacher to have in the face of a mob of people who would seek to damage his life, and that of his family, to show how much they disapproved of what he was trying to do.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”But censoring history is not the only way to go about establishing inaccuracies and ill-informed attitudes about the past. Another option is to spin it.” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Dajani Daoudi is not alone in fighting against the odds to bring research, open thinking and a wide base of knowledge to students. But, as our Spring 2018 issue shows, the odds are starting to stack up against people like him in an increasing number of places.

In 2010, Maureen Freely wrote a piece called Secret Histories for this magazine, about Turkish laws that had kept most of its citizens in the dark about the killings of a million Armenians in the last years of the Ottoman empire, and how those laws were enforced by making certain things – including criticising the legacy of modern Turkey’s founding father, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk – illegal.

Turkey’s government today has just passed a law making mention of the word “genocide” an offence in parliament, as our Turkish correspondent, Kaya Genç, reports on page 22.

But censoring history is not the only way to go about establishing inaccuracies and ill-informed attitudes about the past. Another option is to spin it.

Resisting Ill Democracies in Europe, the excellent report from the Human Rights House Network, acknowledges that a common thread in countries where democracy is weakening is the “reshaping of the historical narrative taught in schools”. In Poland, the introduction of a Holocaust law means possible imprisonment for anyone who suggests Polish involvement in the Holocaust or that the concentration camps were Polish. In Hungary, the rhetoric of the ruling party is to water down involvement of its citizens in the Holocaust and to rehabilitate the reputation of former head of state Miklós Horthy.

At the same time as undermining public trust in the media, governments in this spin cycle seek to stigmatise academics, as well as close down places where open or vigorous debate might take place. The result is often the creation of a “them and us” mentality, where belief in the avowed historical take is a choice of being patriotic or not.

As the HRHN report suggests, “space for critical thinking, independent research and reporting and access to objective and accurate information are pre-requisites for informed participation in pluralistic and diverse societies” and to “debunk myths”.

However, if your objective is not having your myths debunked then closing down discussions and discrediting opposition voices is the ideal way to make sure the maximum number of people believe the stories you are telling.

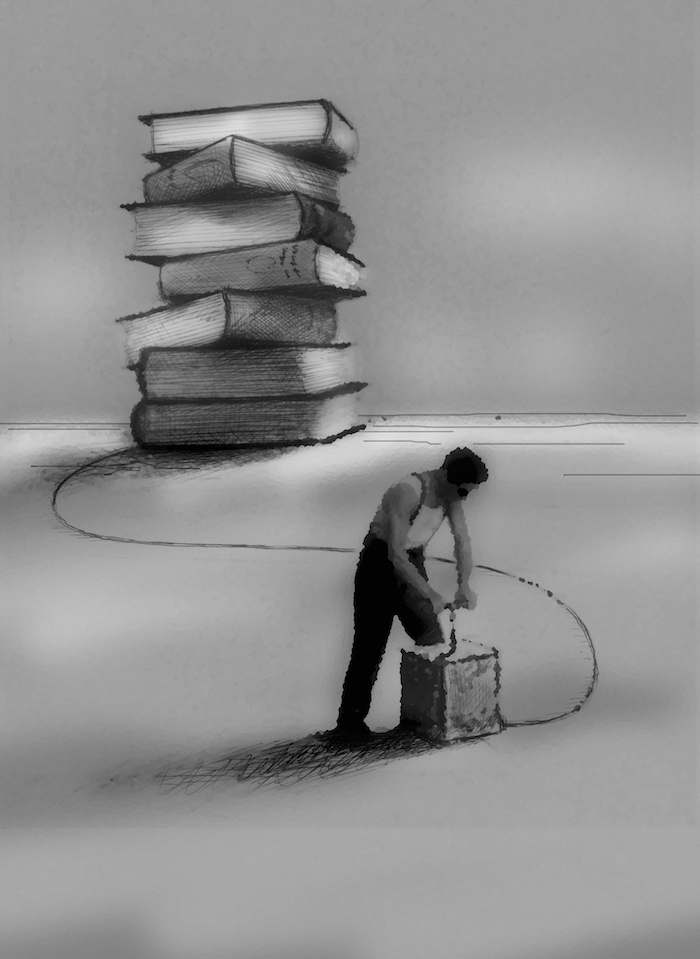

That’s why historians, like journalists, are often on the sharp end of a populist leader’s attack. Creating a nostalgia for a time where supposedly the garden was rosy and citizens were happy beyond belief often forms another part of the political playbook, alongside creating a false history.

Another tactic is to foster a sense that the present is difficult and dangerous because of change and because of threats to “traditional” values; and a sense that history shows a country as greater than it is today. The next step is to find a handy enemy (migrants and LGBT people are often targets) to blame for that change and to stoke up anger.

Access to the past matters. Knowledge of what happened, the ability to question the version you are receiving, and probing and prodding at the whys and wherefores are essentials in keeping society and the powerful on their toes.

In this issue of Index on Censorship magazine, we carry a special report about how history is being abused. It includes interviews with some of the world’s leading historians – Lucy Worsley, Margaret MacMillan, Charles van Onselen, Neil Oliver and Ed Keazor (p31).

We look at how history is being reintroduced into schools in Colombia (p60) and how efforts continue to recognise the victims of General Franco’s dictatorship in Spain (p72). We also ask Hannah Leung and Matthew Hernon to talk to young people in China and Japan to discover what they learned at school about the contentious Nanjing massacre. Find out what happened on page 38.

Omar Mohammed, aka Mosul Eye, writes on page 47 about his mission to retain information about Iraq’s history, despite risk to his life, while Isis set out to destroy historical icons.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Rachael Jolley is editor of Index on Censorship. She tweets @londoninsider. This article is part of the latest edition of Index on Censorship magazine, with its special report on The Abuse of History.

Index on Censorship’s spring 2018 issue, The Abuse of History, focuses on how history is being manipulated or censored by governments and other powers.

Look out for the new edition in bookshops, and don’t miss our Index on Censorship podcast, with special guests, on Soundcloud.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”From the Archives”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”89164″ img_size=”213×287″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064229108535157″][vc_custom_heading text=”Brave new words” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064229108535157|||”][vc_column_text]2010

In 2010, Maureen Freely wrote a piece called Secret Histories for this magazine, about Turkish laws that had kept most of its citizens in the dark about the killings of a million Armenians in the last years of the Ottoman empire[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”90649″ img_size=”213×287″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064220008536796″][vc_custom_heading text=”Censorship in China” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1177%2F0306422013495334|||”][vc_column_text]September 2000

How China attempts to censor, using different methods[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”71995″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064229308535477″][vc_custom_heading text=”Taboos” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1177%2F0306422013513103|||”][vc_column_text]Winter 2015

We tell the story of a Palestinian teacher who took his students to visit Nazi concentration camps in Poland because he felt they should know about the Holocaust. But not everyone agreed.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”The abuse of history” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2018%2F04%2Fthe-abuse-of-history%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The spring 2018 issue of Index on Censorship magazine takes a special look at how governments and other powers across the globe are manipulating history for their own ends

With: Simon Callow, David Anderson, Omar Mohammed [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”99282″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2018/04/the-abuse-of-history/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]