5 Dec 2018 | Artistic Freedom, Awards, Cuba, Fellowship, Fellowship 2019, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Update: All arrested artists have now been released, although they remain under police surveillance. Cuba’s vice minister of culture Fernando Rojas has declared to the Associated Press that changes will be made to Decree 349 but has not opened dialogue with the artists involved in the campaign against the decree.

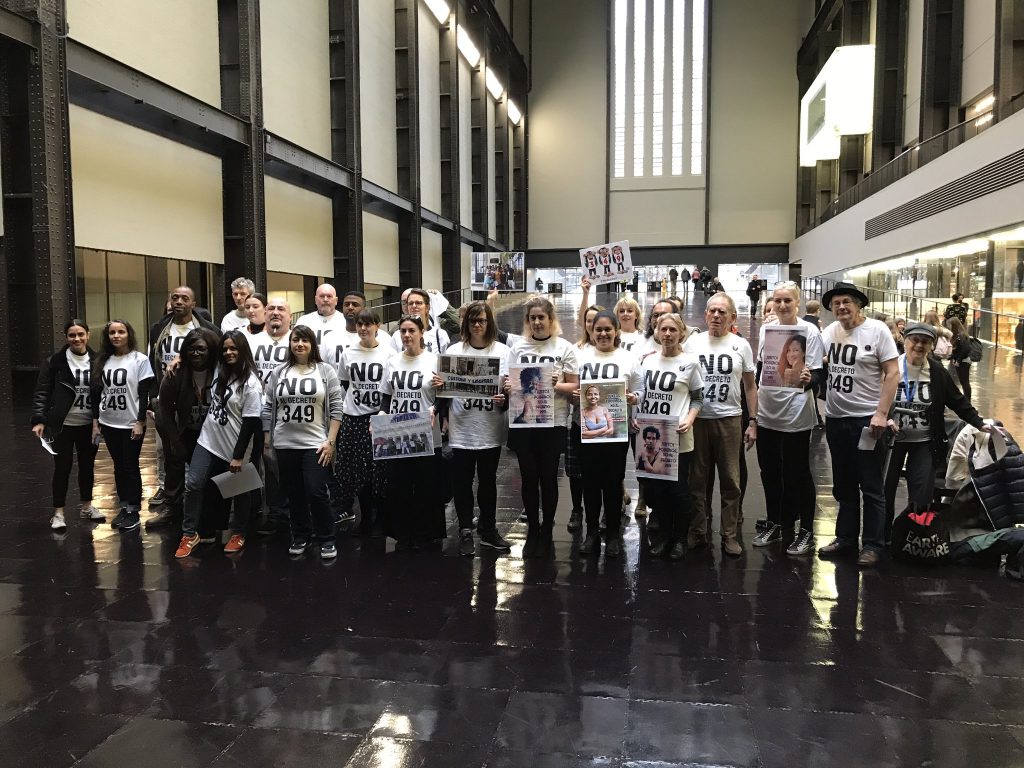

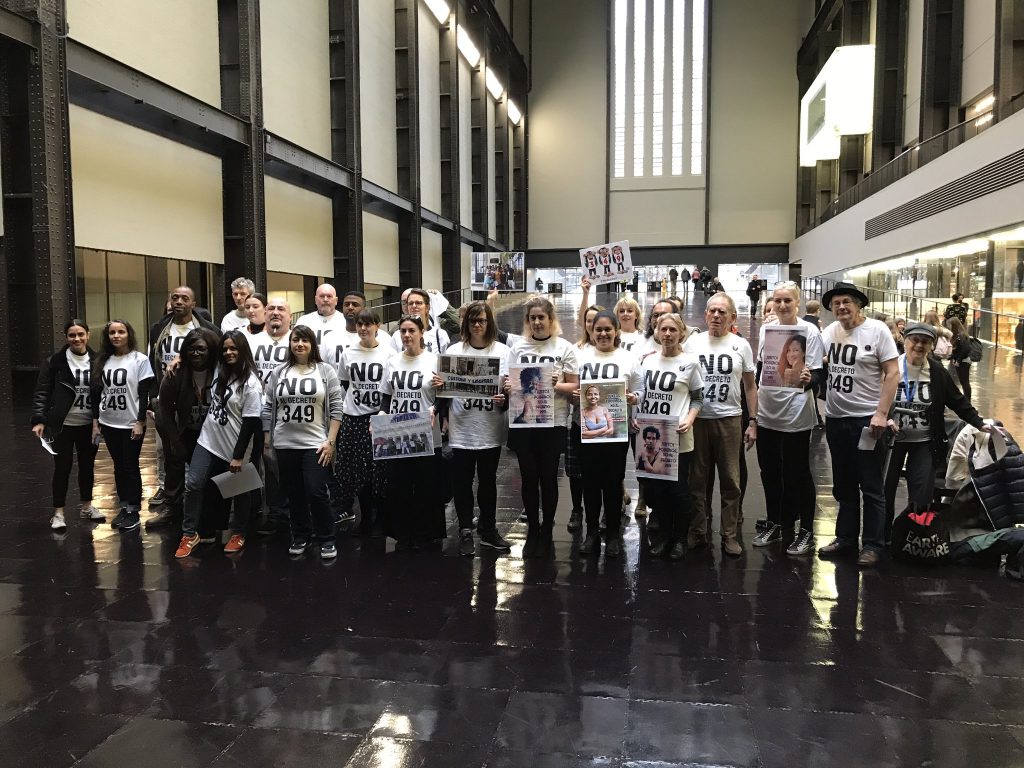

Index on Censorship joined others at the Tate Modern on 5 December in a show of solidarity with those artists arrested in Cuba for peacefully protesting Decree 349, a law that will severely limit artistic freedom in the country. Decree 349 will see all artists — including collectives, musicians and performers — prohibited from operating in public places without prior approval from the Ministry of Culture.

In all, 13 artists were arrested over 48 hours. Luis Manuel Otero Alcantara and Yanelys Nuñez Leyva, members of the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Award-winning Museum of Dissidence, were arrested in Havana on 3 December. They are being held at Vivac prison on the outskirts of Havana. The Cuban performance artist Tania Bruguera, who was in residency at the Tate Modern in October 2018, was arrested separately, released and re-arrested. Of all those arrested, only Otero Alcantara, Nuñez Leyva and Bruguera remain in custody.

Index on Censorship’s Perla Hinojosa speaking at the Tate Modern.

Speaking at the Tate Modern, Index on Censorship’s fellowships and advocacy officer Perla Hinojosa, who has had the pleasure of working with Otero Alcantara and Nuñez Leyva, said: “We call on the Cuban government to let them know that we are watching them, we’re holding them accountable, and they must release artists who are in prison at this time and that they must drop Decree 349. Freedom of expression should not be criminalised. Art should not be criminalised. In the words of Luis Manuel, who emailed me on Sunday just before he went to prison: ‘349 is the image of censorship and repression of Cuban art and culture, and an example of the exercise of state control over its citizens’.”

Other speakers included Achim Borchardt-Hume, director of exhibitions at Tate, Jota Castro, a Dublin-based Franco-Peruvian artist, Sofia Karim, a Lonon-based architect and niece of the jailed Bangladeshi photojournalist Shahidul Alam, Alistair Hudson, director of Manchester Art Gallery and The Whitworth, and Colette Bailey, Artistic director and chief executive of Metal, the Southend-on-Sea-based arts charity.

Some read from a joint statement: “We are here in London, able to speak freely without fear. We must not take that for granted.”

It continued: “Following the recent detention of Bangladeshi photographer Shahidul Alam along with the recent murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi, there us a global acceleration of censorship and repression of artists, journalists and academics. During these intrinsically linked turbulent times, we must join together to defend our right to debate, communicate and support one another.”

Castro read in Spanish from an open declaration for all artists campaigning against the Decree 349. It stated: “Art as a utilitarian artefact not only contravenes the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Cuba is an active member of the United Nations Organisation), but also the basic principles of the United Nations for Education, Science and Culture (UNESCO).”

It continued: “Freedom of creation, a basic human expression, is becoming a “problematic” issue for many governments in the world. A degradation of fundamental rights is evident not only in the unfair detention of internationally recognised creatives, but mainly in attacking the fundamental rights of every single creator. Their strategy, based on the construction of a legal framework, constrains basic fundamental human rights that are inalienable such as freedom of speech. This problem occurs today on a global scale and should concern us all.”

Cuban artists Luis Manuel Otero Alcantara and Yanelys Nuñez Leyva, members of the Index-award winning Museum of Dissidence

Mohamed Sameh, from the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Award-winning Egypt Commission on Rights and Freedoms, offered these words of solidarity: “We are shocked to know of Yanelys and Luis Manuels’s detention. Is this the best Cuba can do to these wonderful artists? What happened to Cuba that once stood together with Nelson Mandela? We call on and ask the Cuban authorities to release Yanelys and Luis Manuel immediately. The Cuban authorities shall be held responsible of any harm that may happen to them during this shameful detention.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1544112913087-f4e25fac-3439-10″ taxonomies=”23772″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

5 Dec 2018 | Artistic Freedom, Artistic Freedom Statements, Cuba, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Cuban artist Tania Bruguera

Update: All arrested artists have now been released, although they remain under police surveillance. Cuba’s vice minister of culture Fernando Rojas has told the Associated Press that changes will be made to Decree 349 but has not opened dialogue with the artists involved in the campaign against the decree.

The following is an open declaration for all artists campaigning against the Decree 349, a law that will criminalise independent artists and place severe restrictions on cultural activity not authorised by the state. It will be read in solidarity at a gathering at Turbine Hall at the Tate Modern today from 1-2pm for those arrested this week for protesting the law. Those arrested include Luis Manuel Otero Alcantara and Yanelys Nuñez Leyva, members of the Index-award winning Museum of Dissidence, and Cuban performance artist Tania Bruguera. In all, 13 artists were arrested over 48 hours. Some have commenced a hunger and thirst strike.

The Cuban government intends to implement a regulation – commonly known as Decree 349 – which will subdue artistic and creative activity on the island, bringing it under the state’s strict tutelage. The content of the decree comprises two classical premises of any totalitarian state: the need for the artist to obtain prior authorisation for the exercise of his/her work and censorship of the creative process.

The execution of these two premises is to be overseen by an intricate structure of civil servants, subject to their discretion, thus reinforcing a “bureaucracy” which inhabits the language of revolutionary self-criticism.

The title of the decree reflects the particular vision that the Cuban government has about art because it refers to “the provision of artistic services”. If the purpose of art is to provide a service, then it essentially provides only to the regime and to no one else.

Art as a utilitarian artefact not only contravenes the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Cuba is an active member of the United Nations Organisation), but also the basic principles of the United Nations for Education, Science and Culture (UNESCO).

The decree does not include anything new to the current practice of the Cuban government in the management of social engineering of its population, however, it offers a legal cover to a reactionary, ancient and regressive practice even in the field of those who consider themselves progressive. Nobody can deny the extraordinary achievement of Cuba in terms of providing basic necessities to its citizens, particularly provisions of health and education; this in spite of a setback of over fifty years, resulting from a political and economic embargo from the world’s most powerful nation. Under these conditions, creatives in Cuba were not only free to practice art but were actively promoted by the State and became a symbol of a global solidarity.

Ultimately, the freedom that is inherent to creative acts is something that a government whose only objective it is to remain in power, will be unable to tolerate. In adopting the act and implementing the decree, they will find themselves in a creative desert that will bore even themselves. The nomenclature living in their material comfort will seek to see Hollywood movies, instead of listening to their own propaganda.

Freedom of creation, a basic human expression, is becoming a “problematic” issue for many governments in the world. A degradation of fundamental rights is evident not only in the unfair detention of internationally recognised creatives, but mainly in attacking the fundamental rights of every single creator. Their strategy, based on the construction of a legal framework, constrains basic fundamental human rights that are inalienable such as freedom of speech. This problem occurs today on a global scale and should concern us all.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1544094682847-9507be49-72bf-3″ taxonomies=”23772″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

5 Dec 2018 | Artistic Freedom, Artists in Exile, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”104099″ img_size=”full”][vc_column_text]“If you want to make films in Burundi, you either self-censor and you remain in the country or if you don’t, you have to flee the country,” Eddy Munyaneza, a Burundian documentary filmmaker, told Index on Censorship.

Munyaneza became fascinated in the process of filmmaking at a young age, despite the lack of cinematic resources in Burundi.

He now is the man behind the camera and has released three documentaries since 2010, two of which have drawn the ire of the Burundian government and forced Munyaneza into exile.

His first documentary — Histoire d’une haine manquée — was released in 2010 and has received awards from international and African festivals. The film is based on his personal experience of the Burundian genocide of 1993, which took place after the assassination of the country’s first democratically elected Hutu president Ndadye Melchoir. It focuses on the compassionate actions he witnessed when his Hutu neighbours saved him and his Tutsi sisters from the mass killings that swept the country. The film launched Munyaneza’s career as a filmmaker.

Munyaneza was honoured by Burundi’s president Pierre Nkurunziza for his first film and his work was praised by government officials. But the accolades faded when he turned his camera toward Nkurunziza for his second film in 2016.

The film, Le Troisieme Vide, focused on the two-year political crisis and president’s mandate that followed Nkurunziza’s campaign for an unconstitutional third term in April 2015. During the following two years, between 500 and 2,000 people were tortured and killed, and 400,000 were exiled.

The filming of his second documentary was disrupted when Munyaneza started receiving death threats from the government’s secret service. He was forced to seek asylum in Belgium in 2016 for fear of his life. Through perseverance and passion, he quietly returned to Burundi in July 2016 and April 2017 to finish his short film.

Exile hasn’t affected Munyaneza’s work: in 2018 he released his third film, Lendemains incertains. It tells the stories of Burundians who have stayed or left the country during the 2015 political tension. He secretely returned to Burundi to capture additional footage for his new film, which premiered in Brussels at the Palace Cinema and several festivals.

“I lead a double life, my helplessness away from my loved ones, and the success of the film on the other,” he said. He continues to work in exile, but also works toward returning to Burundi to see his wife and kids who currently reside in a refugee camp in Rwanda, and to create film, photography and audio programs for aspiring Burundian filmmakers.

Gillian Trudeau from Index on Censorship spoke with Munyaneza about his award-winning documentaries and time in exile.

Index: In a country that doesn’t have an abundance of film or cinema resources, how did you become so passionate about filmmaking?

Munyaneza: I was born in a little village where there was no access to electricity or television. At the age of 7, I could go into town for Sunday worship. After the first service, I would go to the cinema in the centre of the town of Gitega. We watched American movies about the Vietnam war and karate films, as well as other action movies which are attractive to young people. After the film my friends and I would have debates about the reality and whether they had been filmed by satellites. I was always against that idea and told them that behind everything there was someone who was making the film, and I was curious to know how they did it. That’s why since that time I’ve been interested in the cinema. Unfortunately, in Burundi, there is no film school. After I finished school in 2002, I began to learn by doing. I was given the opportunity to work with a company called MENYA MEDIA which was getting into audiovisual production and I got training in lots of different things, cinema, writing, and I began to make promotional films. The more I worked, the more I learned.

Index: How would you characterise artistic freedom in Burundi today, and is that any different to when you were growing up?

Munyaneza: To be honest, Burundian cinema really got going with the arrival of digital in the 2000s. Before 2000 there was a feature film called Gito L’Ingrat which was shot in 1992 and directed by Lionce Ngabo and produced by Jacques Sando. After that, there were some productions by National Television and other documentary projects for TV made in-house by National Television. I won’t say that the artistic freedom in those days was so different from today. The evidence is that since those years, I can say after independence, there have not been Burundian filmmakers who have made films about Burundi (either fictional or factual). There were not really any Burundian films made by independent filmmakers between 1960 and 1990. The man who dared to make a film about the 1993 crisis, Kiza by Joseph Bitamba, was forced to go into exile, just as I have been forced to go into exile for my film about the events of 2015. So if you want to make films in Burundi, you either self-censor and you remain in the country or if you don’t, you have to flee the country.

Index: You began receiving threats after you made your second film, Le troisieme vide, in 2016. The film focused on the political crisis that followed the re-election of president Nkurunziza. Why do you think the film received such a reaction?

Munyaneza: Troisieme Vide is a short film which was my final project at the end of my masters in cinema at Saint Louis in Senegal. I knew that just making a film about the 2015 crisis would spark debate. Talking about the events which led to the 2015 crisis, caused by a president who ran for a third term, which he is not allowed to do by the constitution, I was sure that when this film came out I would have problems with the government. But I am not going to be silent like people who are older than me have done, who did not document what went on in Burundi from the 1960s, and have in effect just made the lie bigger. I want to escape this Burundian fate, to at least leave something for the generations to come.

Index: How did you come to the decision to leave Burundi and what did that feel like?

Munyaneza: Burundi is a beautiful country with a beautiful climate. My whole history is there – my family, my friends. It is too difficult to leave your history behind. The road into exile is something you are obliged to do. It’s not a decision, it’s a question of life or death.

Index: How is life in Belgium, being away from your wife and children?

Munyaneza: It is very difficult for me to continue to live far from my family ties. I miss my children. I remain in this state of powerlessness, unable to do anything for them, to educate them or speak to them. It is difficult to sleep without knowing under what roof they are sleeping.

Index: How has your time in exile affected your work?

Munyaneza: On the work front, there is the film which is making its way. It has been chosen for lots of festivals and awards. I have just got the prize (trophy) for best documentary at the African Movie Academy Award 2018. I was invited but I couldn’t go. I lead a double life, my helplessness away from my loved ones, and the success of the film on the other. I have been invited to several festivals to present my film, but I don’t have the right to leave the country because of my refugee status. I am under international protection here in Belgium.

Index: You have returned to your home country on several occasions to film footage for your films. What dangers are your putting yourself in by doing this? And what drives you to take these risks?

Munyaneza: I risked going back to Burundi in July 2016 and in April 2017 to finish my film. To be honest, I didn’t know how the film was going to end up and sometimes I believed that by negotiating with the politicians it could take end up differently. When you are outside (the country) you get lots of information both from pro-government people and from the opposition. The artist that I am I wanted to go and see for myself and film the situation as it was. Perhaps it was a little crazy on my part but I felt an obligation to do it.

Index: Your most recent film, Uncertain Endings, looks at the violence the country has faced since 2015. In it, you show the repression of peaceful protesters. Why are demonstrators treated in such a way and what does this say about the future of the country?

Munyaneza: The selection of Pierre Nkurunziza as the candidate for the Cndd-FDD after the party conference on 25 April provoked a wave of demonstrations in the country. The opposition and numerous civil society bodies judged that a third term for President Nkurinziza would be unconstitutional and against the Arusha accords which paved the way for the end of the long Burundian civil war (1993-2006). These young people are fighting to make sure these accords, which got the country out of a crisis and have stood for years, are followed. Unfortunately, because of this repression, we are back to where we started. In fact, we are returning to the cyclical crises which has been going on in Burundi since the 1960s. But what I learnt from the young people was that the Burundian problem was not based on ethnic divides as we were always told. There were both Hutu and Tutsi there, both taking part in defending the constitution and the Arusha accords. It is the politicians who are manipulating us.

Index: Do you hold out any hope of improvements in Burundi? Do you hope one day to be able to return to your home country?

Munyaneza: After the rain, the sun will reappear. Today it’s a little difficult, but I am sure that politicians will find a way of getting out of this crisis so that we can build this little country. I am sure that one day I’ll go back and make films about my society. I don’t just have to tell stories about the crisis. Burundi is so rich culturally, there are a lot of stories to tell in pictures.[/vc_column_text][vc_video link=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mnGPlAd1to8&t=24s”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1543844506394-837bd669-b5fd-5″ taxonomies=”29951, 15469″][/vc_column][/vc_row]