31 Mar 2021 | United Kingdom

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]The following are extracts from a letter to Sir Tom Winsor, Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary, from Alice O’Keeffe, an associate editor who worked on the HMIC report, Getting the balance right: An inspection of how effectively the police deal with protests, which was published on 11 March 2021. The subheadings are provided by Index to help guide you through the main points. Read the news story here.

Dear Sir Tom,

I am writing to raise serious and urgent concerns about breaches of the civil service code during a project I was recently involved in as an associate editor for Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary, an inspection into protest policing. The report from the inspection was published on 11 March 2021, and I was involved in drafting and editing the report and other materials related to the inspection from October 2020-March 2021.

.

.

.

The protest policing inspection

The inspection took place in response to a letter from the Home Secretary Priti Patel, on 21st September 2020, asking the inspectorate to look at whether the police needed more legal powers to deal with protest, in response to disruptive protests by Extinction Rebellion and Black Lives Matter, among others. The inspection lead…asked me to edit the report.

.

.

.

The protest policing report

A foregone conclusion?

Early on in the team’s discussions about the inspection, it became clear that the authors of the report had already decided to back the legislative changes proposed by the Met Police and the Home Secretary, which were to be put forward as part of the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill. The purpose of the report was not to collect evidence and then make a decision, but rather to collect evidence to support the decision that had already been made.

There is evidence for this in the letter that I helped to draft from [HMIC] to the Home Secretary, which we began to work on in early November 2020, before the fieldwork stage of the inspection was complete. It said the following:

“We believe all five proposals would improve police effectiveness (without eroding the right to protest) and would be compatible with human rights laws. Moreover, measured legislative reform in these respects would send a clear message to protesters and police forces alike about the limits of the right to protest.”

The Home Secretary replied on 7 December:

“Thank you for your letter… Protests have proved a significant challenge over the last year and I am keen to ensure that the police have the powers and capabilities they need to help address the disruption they face. Your findings will help me to do that.”

This was before the fieldwork phase of the inspection had been completed, discussed and evaluated.

Impartial and independent?

The team was not impartial or independent – and it definitely was not balanced in terms of backgrounds and perspectives. …a serving Chief Inspector for the Metropolitan Police, sat on the team through all the fieldwork evaluation discussions…The Metropolitan Police force was originally responsible for requesting these new powers from the Home Secretary, so I was surprised that a senior serving officer from that force was now acting as an “impartial civil servant” on the question of whether his own force’s requested legislative proposals should be enacted.

Diverse?

Although the inspection very largely concerned the policing of Black Lives Matter protests, there was only one ethnic minority member of an inspection team of 12. There were only two women, including me, although one more joined in the later stages to do some case studies.

I repeatedly [raised] concerns about this, saying that as we did not have anyone with a specialism in equality and race on the team, we might have a “blind spot about race”. I suggested to the team leader… that we should send the report out for external review by a specialist in race and policing – he said there wasn’t time to do that, as the report needed to be published before the Bill came to Parliament for its second reading. On my insistence he did eventually – only days prior to publication – say that he would send it to the Black Police Association to review.

Anti-protestor bias?

In various exchanges I became aware that senior team members held views that were biased against protest groups. For example, in the early stages of the inspection [REDACTED] told me that he had a case study he wanted me to look at, of an individual who he felt should be banned from protesting at all… I assumed that this individual must be a violent offender of some kind. However [REDACTED] told me that the individual in question was one of the founders of…Extinction Rebellion.

[REDACTED] asked for my feedback on the case study. I said that I didn’t think we should include it in the report, as the case would polarise opinion. I made the point that we all needed to keep our personal biases in check. He replied: “So, the following questions spring to mind: If we were writing this report during the ‘troubles’, would it be acceptable for us to show bias against the IRA? If not, what about showing bias against the bombers in particular? In 2020, would it be acceptable to denounce the IRA?”

Reflecting public opinion?

The report presented a skewed account of public opinion on protest policing, by only including select results from the survey that the inspectorate commissioned on the issue. The figure quoted prominently in the report is that “for every person who thought it acceptable for the police to ignore protesters committing minor offences, twice as many thought it was unacceptable.”

However, within the full survey there was a much more mixed response to the issue of how firmly the police should deal with protests. Sixty per cent of people thought it was unacceptable for the police to use force against non-violent protesters, for example. It was unclear to me why this finding should not be of equal importance.

The correct focus?

Late in the report drafting process a member of the team sent me a report, published in July 2020, by SAGE into public order and public health. It set out many concerns that [government scientific advisors] SAGE had about policing protest in the context of the pandemic. The SAGE report makes it very clear that the public order threat comes from both BLM-type protests inspired by racial inequality, and from the extreme right-wing (XRW).

The report says: “XRW groups are coalescing and mobilising at a scale not witnessed since the early EDL protests around 2010. There is a substantial overlap between some of the issues foregrounded by these groups (e.g. protection of heritage, memorials) and much larger sections of the population, e.g. among veterans… Large-scale confrontations provoked by the XRW in London and then subsequently in Glasgow, Newcastle and other cities were partly responses to the previous actions of hardcore elements of BLM and the anti-Fascist movement and perceptions of weakness among the police.”

.

.

.

At no point throughout the whole process of putting the protest policing report together had the team ever discussed the public order threat presented by right-wing groups. I sent an email to [REDACTED] on 12 February saying that I felt “we have missed a ‘piece of the puzzle’ when it comes to the rise of the far right.” He said he would consider this, but it was very late in the process and nothing was ever done about it.

In the published report, the far-right are only mentioned once, on p.130. This is the section in which the authors argue in favour of aligning legislation on processions and assemblies, giving the police the power to ban assemblies. It becomes clear at this point that in fact this power is – contrary to the report’s exclusive focus on other protests – much more likely to be necessary in dealing with far-right protests.

The report says: “We learned that, between 2005 and 2012, Home Secretaries signed 12 prohibition (banning) orders on processions. Ten of these were associated with far-right political groups. The other two were associated with anti-capitalist and anti-globalisation groups.”

Events after publication

The headline finding of the report into protest policing was that the balance had tipped “too readily in favour of protesters.” It said that a “modest reset of the scales is needed” away from the rights of protesters, and towards the rights of “others”.

The weekend following the report’s publication, the vigil to mark Sarah Everard’s murder took place in London.

I wrote to [REDACTED] on Sunday morning, saying that I felt the inspectorate had serious questions to answer around whether our protest policing report had “contributed – albeit unintentionally – to an environment in which the Met felt at liberty to prohibit, and then clamp down forcefully on, a peaceful protest by women, against the murder of a woman by a serving police officer.”

I added that I hoped the inspectorate would “make it clear to the Met that its handling of this vigil was completely unacceptable and disproportionate.”

On Monday morning, I received a phone call from my manager to say that the inspectorate had been commissioned by the Mayor of London and the Home Secretary to inspect the behaviour of the Met at the Sarah Everard vigil. He asked me to edit it. I said that I would, but I wanted the team to know that as an editor I would need to ask robust questions about the role of our previous protest policing report in the decisions that had been made by the Met Police that night.

Later that day, I received a follow-up email from my manager to say that [REDACTED] had requested another editor, as he felt “he needed an editor who’d be able to approach this job with an open mind. Based on your email, he didn’t feel that would be possible.” I was replaced by [an] editor with no background in protest policing work.

I acknowledge that, in shock at the events at the Sarah Everard vigil, I expressed the view that the Met had acted disproportionately. This was, and remains, my personal view. I regret making that comment and acknowledge that it did not demonstrate the impartiality that I have always upheld in the context of my role.

However, I believe that I was raising important concerns about a conflict of interest, and the impact of the previous report.

.

.

.

I am a committed civil servant and as such I feel it is urgently necessary for the Inspectorate, and the Civil Service Commission, to address some of these issues, both in terms of this immediate inspection, and in the longer term. Much more needs to be done to ensure proper independence, which means a clear separation between the Inspectorate, the police and other institutions such as the College of Policing. It also means working much harder to ensure that the staff on inspection teams have a diverse mix of backgrounds and perspectives, and that discussions and processes can be truly free, fair and impartial.

Yours faithfully,

Alice O’Keeffe

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

30 Mar 2021 | China, News and features

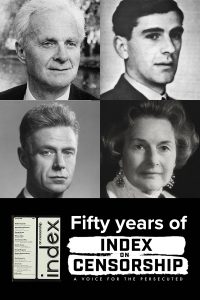

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”116480″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]Last week, the Chinese government outlined sanctions against nine British individuals and three organisations for daring to speak out about what is going on in Xinjiang.

Those affected by the sanctions are former Conservative party leader Iain Duncan Smith, Tom Tugendhat, chair of the foreign affairs select committee, Nus Ghani from the business select committee, Neil O’Brien, head of the Conservative policy board and China Research Group officer, Tim Loughton of the Inter-Parliamentary Alliance on China, crossbench peer David Alton, Labour peer Helena Kennedy QC and barrister Geoffrey Nice.

The only individual not from the political sphere is Dr Joanne Smith Finley, Reader in Chinese studies at Newcastle University.

The organisations include the China Research Group, the Conservative Human Rights Commission and Essex Court Chambers.

China made the move after the British government imposed sanctions on four Chinese officials and one organisation last Monday: Zhu Hailun, former secretary of the political and legal affairs committee of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR); Wang Junzheng, deputy secretary of the party committee of XUAR; Wang Mingshan, secretary of the political and legal affairs committee of XUAR; Chen Mingguo, vice chairman of the government of the XUAR, and director of the XUAR public security department; and the Public Security Bureau of the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps – a state-run organisation responsible for security and policing in the region.

A statement from Tom Tugendhat and Neil O’Brien on behalf of the China Research Group said, “Ultimately this is just an attempt to distract from the international condemnation of Beijing’s increasingly grave human rights violations against the Uyghurs. This is a response to the coordinated sanctions agreed by democratic nations on those responsible for human rights abuses in Xinjiang. This is the first time Beijing has targeted elected politicians in the UK with sanctions and shows they are increasingly pushing boundaries.

“It is tempting to laugh off this measure as a diplomatic tantrum. But in reality it is profoundly sinister and just serves as a clear demonstration of many of the concerns we have been raising about the direction of China under Xi Jinping.”

Commenting on China’s decision, foreign secretary Dominic Raab said: “It speaks volumes that, while the UK joins the international community in sanctioning those responsible for human rights abuses, the Chinese government sanctions its critics. If Beijing want to credibly rebut claims of human rights abuses in Xinjiang, it should allow the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights full access to verify the truth.”

Meanwhile, Prime Minister Boris Johnson said, “The MPs and other British citizens sanctioned by China today are performing a vital role shining a light on the gross human rights violations being perpetrated against Uyghur Muslims. Freedom to speak out in opposition to abuse is fundamental and I stand firmly with them.”

Newcastle University academic Dr Joanne Smith Finley believes she has been sanctioned because of her “ongoing research speaking the truth about human rights violations against Uyghurs and other Turkic Muslims in Xinjiang”

“In short, for having a conscience and standing up for social justice,” she said.

She said, “That the Chinese authorities should resort to imposing sanctions on UK politicians, legal chambers, and a sole academic is disappointing, depressing and wholly counter-productive.”

Dr Smith Finley has studied China for many years.

“I began my journey to become a ‘China Hand’ in 1987, when I enrolled at Leeds University to read modern Chinese studies. My first year spent in Beijing in 1988-89 – during which I also experienced the ‘Tianan’men incident’ – ensured that China entered my bloodstream forever, and the city became my second home,” she said. “I later focused on the situation in the Uyghur homeland (aka Xinjiang), to which I made a series of field trips, long- and short-term-, between 1995 and 2018.”

Dr Smith Finley said since taking up her post at Newcastle University in 2000, she has worked tirelessly to introduce students from the UK, Europe and beyond to the world of Chinese society and politics.

“I have prepared successive student cohorts for their immersion in Chinese culture, and have visited our students each year in situ across five Chinese cities,” she said.

“When China applies political sanctions to me, it thus stands to lose an erstwhile ally,” she said. “Since 2014, I have watched in horror the policy changes that led to an atmosphere of intimidation and terror across China’s peripheries, affecting first Tibet and Xinjiang, and now also Hong Kong and Inner Mongolia.”

“In Xinjiang, the situation has reached crisis point, with many scholars, activists and legal observers concluding that we are seeing the perpetration of crimes against humanity and the beginnings of a slow genocide. In such a context, I would lack academic and moral integrity were I not to share the audio-visual, observational and interview data I have obtained over the past three decades.”

“I have no regrets for speaking out, and I will not be silenced. I would like to give my deep thanks to my institution, Newcastle University, for its staunch support for my work and its ongoing commitment to academic freedom, social justice and inter-ethnic equality.”

Following the announcement of sanctions against Dr Smith Finley, more than 400 academics have written an open letter to The Times in support, asserting their commitment to academic freedom and calling on the Government and all UK universities to do likewise.

There are increasing demands from human rights activists to take action over China’s ‘soft genocide’ in Xinjiang. Tit-for-tat sanctions will not resolve the issue. That will take much firmer action from governments, organisations and individuals who are complicit in the subjugation of the Uyghurs, by buying Chinese products and accepting money built on their suffering.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You may also want to read” category_id=”85″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

26 Mar 2021 | 50 years of Index, Opinion, Ruth's blog

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

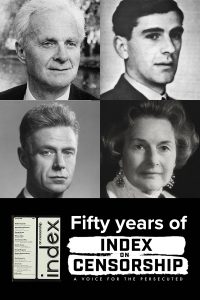

Clockwise from top left: Poet Stephen Spender, codebreaker and historian Peter Calvocoressi, biographer Elizabeth Longford (© National Portrait Gallery, London) and philosopher Stuart Hampshire (The British Academy)

The founding story of Index is such an emotive one, at least for me. A challenge was laid at the feet of some of the great and the good – a global call for solidarity with those thinkers and creative beings who were living under a repressive regime. Supporting those dissidents who were standing against totalitarianism. Providing hope, solidarity and most importantly a platform to publish their work, to tell their stories.

50 years ago this week, four extraordinary people signed our charitable deeds founding Index on Censorship – Stephen Spender, Elizabeth Longford, Stuart Hampshire and Peter Calvocoressi. Their vision was clear – we were to be a voice for the persecuted, providing a home for dissident writers, scholars and artists and to shine a light on the actions of repressive regimes. You can read more on our amazing founders here – www.indexoncensorship.org/50yearsofindex

I think we’ve lived up to their vision.

Over the last half century, with the help of so many, we’ve featured the works of inspirational dissident writers from Vaclav Havel to Salman Rushdie to Ma Jian. We’ve covered every aspect of censorship throughout the world from journalists being assassinated to governments restricting access to the internet. We’ve run successful campaigns on issues as varied as libel reform in the UK to hate speech. We’ve exhibited the work of artists and writers from repressive regimes at the Tate Modern and the British Library. And we’ve supported more than 80 Freedom of Expression award winners in the last 20 years – telling their stories and supporting their work.

There have been heartbreaking moments throughout our history, as friends were arrested for demanding their rights to free speech, as protesters were gunned down by repressive regimes, as democratic countries became more authoritarian and people because increasingly silenced. Our hearts bled, but our determination to be their voice, to fight with them and for them became stronger and stronger.

Birthdays provide a moment for reflection. By their very nature, you explore the past – what went well, what didn’t? What should we be doing in the years ahead, what should we be focusing on. On our 50th birthday, what is clear is that our work is not done. That too many people are still being silenced, so we will keep fighting the good fight.

Because of the impact of Covid-19 we aren’t going to get to have a big birthday party this month (although I’m adamant we will to celebrate 50 years of the magazine next year), but we won’t let our 50th birthday go unmarked either

You’ll have seen our new branding for Index. Next month we’ll have a new design for the magazine, which I hope you’ll love – the team have done an amazing job. We have lots of plans for the months ahead – and I hope that you’ll be with us for the fights ahead.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You may also want to read” category_id=”41669″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

24 Mar 2021 | 50 years of Index

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”116457″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]Of the “gang of four” who signed the documents establishing the Writers and Scholars Education Trust fifty years ago on 25 March 1971, Peter Calvocoressi perhaps embodied the spirit of that trust more than the other three. He was both writer and scholar. And many things besides.

In 1968, Calvocoressi published what became the definitive work on post-war global history, World Politics Since 1945. The book, which the Sunday Times called “masterly”, has remained in print ever since and stretches to almost 900 pages.

It is one of more than 20 books he wrote during his lifetime, which stretched from a Who’s Who in The Bible to Suez: Ten Years After.

His academic credentials were equally impressive: he was Reader in International Relations at the University of Sussex, a post created especially for him.

The Calvocoressi name hints at his most international of upbringings. He was born in Karachi, in what is now Pakistan, but then was British India, making him a British subject. However, in one of his autobiographical works he considered himself “entirely Greek”, being part of the Ralli family who left the Aegean island of Chios in the 19th century diaspora.

Peter’s parents moved to London in 1910 and he was born two years later. Peter was educated at Eton and Balliol College, Oxford where he got a first in modern history.

He was called to the Bar in 1935 and shortly thereafter was recruited into the Ministry of Economic Warfare, based at the London School of Economics.

Soon after the start of the Second World War, Calvocoressi resolved to volunteer to become more active in the war effort. After a day of tests at the War Office he was told he was “no good, not even for intelligence”.

That conclusion proved to be very wrong. Soon after, through a contact, he was interviewed by the Air Ministry and shortly after became an RAF intelligence officer. In 1942, his gift for languages saw him plucked out for duty to Bletchley Park, the wartime home of the Allied codebreakers.

There he worked in the famous Hut 3, which decrypted messages from Germany’s Enigma machines and passed intelligence, known as Ultra, to the Allies’ military commanders. His time at Bletchley, where he went on to lead Hut 3, is described in his revelatory book Top Secret Ultra, published in 1980, shortly after the activities of the Allied codebreakers were first made public.

After the war, Calvocoressi was asked to participate in the Nuremberg Trials, helping obtain evidence for the Allied prosecution team and in which he cross-examined former German Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt.

Calvocoressi spent much of the Fifties researching and writing his Survey of International Affairs series, revealing his firm grasp of global politics and international relations.

He was asked to join the council of the International Institute for Strategic Studies in 1961 and later was instrumental in the early years of Amnesty International.

In 1967, he was called on as an independent expert to find out whether Amnesty had been infiltrated by British intelligence agents – his investigation proved that it had not. He steadied the ship at the organisation and served on its board from 1969 to 1971.

Throughout the decade, Calvocoressi was a member of the UN’s Commission on discrimination and the protection of minorities and became a member and chairman of the Africa Bureau, which lobbied against apartheid, at the request of his friend David Astor, owner and editor of The Observer.

Calvocoressi’s international experience and erudition made him an obvious choice to be asked to help found the Writers and Scholars Educational Trust, the organisation that is today better known by its working name of Index on Censorship.

Calvocoressi contributed to Index’s work in the early years but the world of publishing came calling.

He became a partner in publishers Chatto & Windus and Hogarth Press and was later asked to be chief executive of Penguin Books, a position he held until 1976. He continued his prodigious writing output throughout the Eighties and Nineties.

He had strong freedom of expression values too. He believed in the freedom to publish – writing a book of the same name which Index published in 1980.

He also believed in the freedom of the press but not at any cost.

In the case of the Pentagon Papers, the revelations around US involvement in the Vietnam War, he wrote to the Sunday Times about the decision of US newspaper editors to publish them.

He wrote: “The newspapers maintained that they were entitled to print the Pentagon Papers because the documents had come into their possession and they themselves judged that publication could not harm national security.

“But is an editor in a position to judge this? Surely not, for he cannot know enough of the background to tell whether he is giving something away.”

“Governments must have secrets whether we like it or not, and the power to preserve them. I am not denying that our own government overdoes the secrecy, sometimes absurdly so.”

What readers of that letter did not know, of course, was Calvocoressi’s personal involvement in the biggest secret of the war: the codebreaking at Bletchley Park.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]