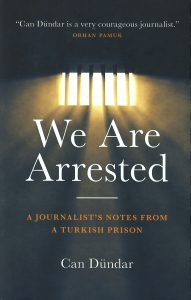

Can Dündar

Can Dündar is an award-winning Turkish journalist, documentary filmmaker and author. He was arrested in 2015 for his work and now lives in exile in Germany.

Can Dündar is an award-winning Turkish journalist, documentary filmmaker and author. He was arrested in 2015 for his work and now lives in exile in Germany.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text] The Royal Shakespeare Company performed an abridged version of Turkish journalist Can Dündar’s book We Are Arrested on stage at the Other Place in Stratford-upon-Avon on Friday 16 June. The plot follows Dündar’s arrest and imprisonment after his decision as editor-in-chief of Cumhuriyet newspaper to publish evidence of Turkish intelligence services sending weapons to Syria.

The Royal Shakespeare Company performed an abridged version of Turkish journalist Can Dündar’s book We Are Arrested on stage at the Other Place in Stratford-upon-Avon on Friday 16 June. The plot follows Dündar’s arrest and imprisonment after his decision as editor-in-chief of Cumhuriyet newspaper to publish evidence of Turkish intelligence services sending weapons to Syria.

Cumhuriyet received the Reporters without Borders (RSF) Press Freedom Prize in 2015 for its reporting despite being the target of “frequent persecution by the Turkish regime”.

The performance featured two actors, with the audience seated in a square formation surrounding the performers. The actors used two chairs as props. One actor played Dündar and narrated the plot, while the second actor played the other characters who interacted with him, including his son, his wife and fellow Cumhuriyet journalist and prisoner Erdem Gül.

In November 2015, Dündar and Gül were charged with espionage for exposing secret information. In the play, his character described the decision to publish the evidence that landed him in jail, which was printed under the headline: The weapons denied by Erdogan. Several times throughout the reading, Dündar’s character reiterated the guiding principles that led him to print: Is the work genuine? Is it in the public interest? If it is more valuable to publish the work than to “put it in a drawer,” then it is a journalist’s civic duty to publish.

While waiting to hear the charges against him, Dündar drew on George Orwell for moral support, quoting: “During times of universal deceit, telling the truth becomes a revolutionary act.”

In February 2016, the Turkish Supreme Court declared Dündar’s imprisonment unlawful and ordered his release. He described his release as moving from “the closed prison of Silivri to the semi-open prison that is Turkey”.

Since then, Dündar has lived in exile in Berlin. His wife, Dilek Dündar, is unable to leave Turkey, where she has lived “like a hostage” ever since her passport was confiscated. Most of the characters in the play are now in jail, including three of Dündar’s lawyers and a dozen Cumhuriyet journalists have been arrested. Press freedom in Turkey has been on the decline, falling from 98th in the world in 2005 to 155th in 2017 according to RSF’s World Press Freedom Index.

Dündar spoke to Index following the play about those journalists and defenders of freedom of expression still imprisoned in Turkey. “We have to defend their job and their freedoms and we have to be brave,” he said. “Being talented is not enough – you have to be brave at the same time. We will prevail in the end.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1497951623613-7ff5d7eb-a81e-2″ taxonomies=”7789″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content_no_spaces” content_placement=”middle”][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”91122″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/05/stand-up-for-satire/”][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

What is usually the first pledge made by a politician who has won an election in his victory speech?

Erdogan’s was the death penalty.

Before the result of the 16 April referendum, which ended neck and neck, was even clear he came out onto the balcony and gave the “good news” to his supporters shouting “we want the death penalty!” that they would soon get their wish.

By abolishing the death penalty at the start of the 2000s, Turkey overcame an important obstacle in its negotiations with Europe. Now Erdogan is planning to bring back the death penalty, bombarding relations with Europe which are already at breaking point. And it was not just this. Two days after the referendum the government took the decision to extend the State of Emergency by three months. The extension of this emergency regime, which has been in force since 15 July 2016, was a concrete response to those expecting Erdogan to loosen the reins after the referendum. Sadly, Turkey now awaits not a time of relative peace, but a much more intense and chaotic period of repression.

There are a few different reasons for this.

The first is that it has become understood that Erdogan actually lost the referendum… Had the Supreme Electoral Board not taken the decision to count invalid votes as valid before the voting had even ended, Erdogan would not now be an executive president: he would be a leader who had lost a referendum. Since that day, hundreds of thousands of people have protested in the streets, shouting that their votes had been stolen. These protests have frightened the government, afraid they might turn into the Gezi uprisings of four years before. This is one reason for the increase in repression…

Another reason is that Erdogan has lost the big cities for the first time… The AKP, which has held onto key cities such as Istanbul and Ankara throughout its 15 years of power, has been beaten in these cities for the first time in this referendum. If we consider that Istanbul is the city in which Erdogan began his political career, it’s possible to say that his fall has also begun there. This is something that Erdogan will be losing sleep over…

Add to this disgruntlement an economy in the doldrums, especially with the wiping out of tourism revenues, and the withdrawal of the support from European capitals that had been given in pursuit of a refugee agreement, and you can understand why Erdogan is under so much pressure.

Now his only support comes from the Trump regime, which needs their help in Syria, from international capital which prefers authoritarian power to democratic chaos and from the social democratic opposition, still searching for a solution through a legal system that has long ago passed into Erdogan’s hands…

Can Erdogan balance out his shunning by Europe with the relationships he is striving to build with Trump and Putin?

By being part of the Syrian war, can he undo the tensions that are mounting at home?

Can he rein in the growing Kurdish problem by keeping jailed the co-presidents and around 10 MPs belonging to the HDP, the political representatives of the Kurds?

Can he hide the repression, lawlessness, and theft by jailing 150 journalists, silencing hundreds of media organs, throwing the foreign press out of the country and even punishing those who tweet?

I don’t think so.

All the data points to this last referendum being the beginning of the end for Erdogan. He will not go quietly, because he can guess what will happen to him if he loses power. But from here on in, he will pay a heavy price for every repressive act.

Just before the referendum, Theresa May visited Turkey and, turning a blind eye to the human rights violations, signed a contract for the construction of warplanes. Things in Ankara may have changed a great deal by the time those planes are ready.

Maybe in London too…

Yet those in Turkey fighting at the cost of their lives for democracy, a free media, and gender equality will never forget that the leader of a country accepted as “the cradle of these principles” did not even once mention them when she arrived in Ankara to trade arms.

Seçim kazanmış bir siyasetçinin zafer konuşmasında ilk vaadi ne olabilir?

Erdoğan’ınki idam cezası oldu.

16 Nisan’da yapılan ve neredeyse başabaş sona eren referandumun kesin sonuçları açıklanmadan, sarayının balkonuna çıktı ve “İdam isteriz” diye bağıran taraftarlarına, istediklerine çok yakında kavuşacakları “müjdesini” verdi.

Türkiye, idam cezasını 2000’lerin başında kaldırarak, Avrupa ile müzakerelerin önündeki önemli bir engeli aşmıştı. Şimdi Erdoğan, idam cezasını yeniden getirerek Avrupa ile zaten kopma noktasındaki ilişkileri bombalamaya hazırlanıyor.

Sadece o da değil, referandumdan iki gün sonra Hükümet, Olağanüstü Hal’i üç ay daha uzatma kararı aldı. 15 Temmuz darbe girişiminden beri uygulanan sıkıyönetim rejiminin uzatılması, referandumdan sonra Erdoğan’ın ipleri gevşeteceğini bekleyenlere somut bir cevap oldu.

Ne yazık ki, Türkiye’yi huzur değil, çok daha ağır ve kaotik bir baskı dönemi bekliyor.

Bunun birkaç nedeni var:

Birincisi, referandumu Erdoğan’ın aslında kaybettiğinin anlaşılması… Henüz sandıklar kapanmadan, Yüksek Seçim Kurulu’nun aldığı bir kararla, geçersiz oylar geçerli sayılmasa, Erdoğan şu an Başkan değil, referandum kaybetmiş bir liderdi. O günden beri, yüzbinlerce insan caddelerde oylarının çalındığını haykırarak protesto gösterisi yapıyor. Bu protestoların, 4 yıl önceki Gezi ayaklanmasına dönüşmesi, iktidarı korkutuyor. Baskının artırılmasının bir nedeni bu…

Bir başka neden, Erdoğan’ın ilk kez büyük kentleri kaybetmiş olması… 15 yıllık iktidarı boyunca İstanbul, Ankara gibi kilit kentleri elinde tutan AKP, ilk kez bu referandumda bu şehirlerde yenildi. İstanbul’un, Erdoğan’ın siyasi kariyerine başladığı kent olduğu düşünüldüğünde, düşüşünün de oradan başladığını söylemek mümkün. Bu da, Erdoğan’ın uykularını kaçıran bir unsur…

Bu huzursuzluğa bir de özellikle turizm gelirlerinin sıfırlanmasıyla düşüşe geçen ekonomiyi ve Avrupa başkentlerinin mülteci anlaşması uğruna verdikleri desteği çekmesini ekleyin; Erdoğan’ın neden bu kadar sıkıştığını anlarsınız.

Şimdi tek dayanağı, Suriye’de kendisine ihtiyaç duyan Trump rejimi, demokratik bir kaos yerine otoriter bir istikrarı tercih eden uluslararası sermaye ve çareyi çoktan Erdoğan’ın eline geçmiş yargı sisteminde arayan sosyal demokrat muhalefet …

Erdoğan, Avrupa’dan dışlanışını, Trump ya da Putin’le kurmaya çabaladığı ilişkiyle dengeleyebilir mi?

Suriye savaşına dahil olarak, içerde yaşadığı gerilemeyi tersine çevirebilir mi?

Kürtlerin siyasi temsilcisi olan HDP’nin eşbaşkanlarını ve 10’u aşkın milletvekilini hapiste tutarak tırmanan Kürt sorununu dizginleyebilir mi?

150 gazeteciyi hapsedip, yüzlerce medya organını susturarak, yabancı basını ülkeden kovup tweet atanları bile cezalandırarak, yaşanan baskıları, hukuksuzlukları, hırsızlıkları saklayabilir mi?

Bence hayır.

Bütün veriler, son referandumun Erdoğan için sonun başlangıcı olduğunu ortaya koyuyor. Düşerse başına gelecekleri tahmin ettiği için kolay çekilmeyecektir. Ancak bundan sonra her yapacağı baskı için ağır bedel ödeyecektir.

Başbakan Theresa May’in tam referandum öncesi yaptığı Türkiye ziyaretinde, insan hakları ihlallerini görmezden gelerek yapımına imza attığı savaş uçakları hazır olduğunda, Ankara’da işler hayli değişmiş olabilir.

Belki Londra’da da…

Yine de demokrasi için, özgür medya için, laiklik için, kadın-erkek eşitliği için canı pahasına mücadele veren Türkiyeliler, “bu ilkelerin beşiği” kabul edilen ülkenin liderinin silah ticareti için geldiği Ankara’da, bu ilkeleri ağzına bile almamasını asla unutmayacaktır.

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1493982838323-862a9fef-6b14-3″ taxonomies=”8607″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Can Dündar, Houses of Commons, 29 June. Credit: Flickr / Centre for Turkey Studies

In mobster movies the bad guys always kidnap the wife of the protagonist. They’ll phone the husband to say: “We have your wife. Do as we tell you otherwise she’s gone.”

I had not imagined that a state could become no better than a criminal syndicate. But the Turkish state has become one.

On Saturday 3 September my wife’s passport was confiscated by the police at the airport as she was en route to Berlin. She was not accused of anything criminal. She was not being searched for or tried and had no obstacles preventing her from travelling abroad. There was no legitimate reason to prevent her journey and no explanation has been given.

It is with me that they had an issue. I had broadcast footage of Turkish state intelligence smuggling arms into a neighbouring country by illegal means. They could not deny it and say: “No such thing has happened.” What they said was: “This is a state secret.”

For uncovering the state’s dirty secrets, I was given five years and ten months in prison. We had appealed the conviction to a higher court but after the coup attempt a state of emergency was declared and the rule of the law was completely suspended.

To expect justice to be served by a judiciary under the complete control of the government would have been as naive as expecting mercy from the “mob”.

I went abroad and said that I would not return until the state of emergency was lifted and the rule of the law was restored.

Then the mob took my wife hostage. We are not the only people to face such relentlessness.

The 64-year-old mother-in-law of one of the supposed coup plotters was taken to a prison in a wheelchair. The father of another accused, who was not caught, was taken into custody as he left prayer in a mosque. The passports of wives and daughters have been confiscated and hundreds of families have been forcefully separated without trial.

These are direct violations of the principle of individual responsibility for crime.

Guilt by association allows such mob-like lawlessness prevails in a country that is a member of the Council of Europe.

It was the present government that brought the coup plotters who tried to overthrow it into the state, tasked them with cleansing its opponents and made a giant out of them.

When they had a dispute over distribution of spoils and dissolved their partnership, there remained within the state a well rooted and gargantuan parallel organisation.

Then the conflict peaked on July 15 when Frankenstein’s monster attacked its creator.

The violent coup attempt was put down because the military headquarters did not lend it support and the people took to the streets. But Erdogan has treated the event — in his own words — as “a godsend”. Using the tactics used by US senator Joseph McCarthy in the 1950s, he has started a witch hunt that will incarcerate all opposition.

More than 40,000 people have been taken into custody while 80,000 civil servants have been removed from their duties. Dozens of journalists have been arrested. Nearly 100 media outlets have been shut down.

Yet the rage of the government has not been quelled. Now it is taking it out on the relatives of those “witches” it did not catch.

It says: “We have your wife. Come back or she’s gone.”

But we all know that at the end of the movie the bad guys are defeated, the hostages are freed and families are reunited.

I have no doubt that this is what will happen in Turkey. Those who have made a mob out of the state will be tried. Families will get back together and celebrate the end of the witch hunt and the return of freedom, democracy and justice.

We are well aware of this and we labour to make that day come true.

Can Dündar: Turkey is “the biggest prison for journalists in the world”

Turkey should drop criminal charges against journalists Can Dündar and Erdem Gül