6 Jan 2023 | News and features, Volume 51.04 Winter 2022, Volume 51.04 Winter 2022 Extras

Pavel Litvinov, who recently turned 82, is an imposing figure. When I meet him on a rainy August day, he fills the space in his compact living room in the suburban New York City garden apartment he shares with his wife, Julia Santiago. We picked the day, 22 August, for our interview out of convenience, but it happens to resonate. It was on 21 August 1968 that Soviet troops invaded Czechoslovakia, demolishing the “socialism with a human face” of its leader, Alexander Dubček.

Days later, at noon on 25 August, the then 28-year-old physicist Litvinov, with seven comrades – including the group’s organiser, poet Natalya Gorbanevskaya (and her baby in a pram) – met in Moscow’s Red Square to unfurl a banner that turned out to be life-changing. Its message was plain: “Hands off the CSSR [Czechoslovak Socialist Republic].” Within minutes, the KGB arrived to forcibly take them away to camps or psychiatric hospitals. Litvinov, hit hard in the face, was arrested and sent to internal exile in a Siberian mining town for five years with his then wife. His daughter was born there.

“I was in prison for several months and then in exile and had to work in the mines. I couldn’t leave the village; I couldn’t get permission to travel,” Litvinov said. Recalling his motivation for the action, he added: “It felt internally necessary. I had a very strong feeling of what is fair and unfair, and that people have to treat each other gently and with respect.”

The Litvinov family was well known in both dissident and Soviet ruling circles. His grandfather was Maxim Litvinov, once Joseph Stalin’s people’s commissar for foreign affairs until he was deposed in 1939 because, as a Jew, he became an obstacle to warmer ties with Adolf Hitler. “I was 11 when my grandfather died; we were good friends,” he explained. “He was already disappointed in the Russian revolution and the Bolsheviks.” His parents’ home was a gathering place for dissidents. Literature also inspired him. “Most important was Russian literature from the 19th century –Pushkin, Tolstoy, Lermontov… They expressed a feeling of compassion toward helping others under the autocratic state,” he said.

Indeed, books and literature, in the form of samizdat, were crucial – not only the literary classics but also records of the dissidents’ trials in real time. Litvinov deconstructs the samizdat publication process for me, explaining how, during these trials, somebody would gain access to the court and bring the information home. “They would write the transcript by hand; then we would find someone who had a typewriter,” he said. “I would print pages on very thick photographic paper. The book would be photographed and developed in a darkroom. Sometimes we would have a party to read the book. I would read the first page, give [someone else] the second page, who would give it to the next one. We would read Doctor Zhivago in half a night, then have tea or vodka. Then I would give a film to a friend from Leningrad, and someone would come from Kyiv – same procedure.”

From his earliest dissident days, Litvinov’s strategy was to appeal to allies outside the Soviet Union. And that’s the connection to Index on Censorship. In 1968, he co-wrote with dissident Larisa Bogoraz an Appeal to World Public Opinion, about dissident trials. “I wrote the appeal in Russian. Some of the foreign correspondents translated it to English. In the evening we would always listen to the BBC. They started to speak about the letter. They said Stephen Spender read about it… and Spender called Igor Stravinsky, Mary McCarthy[and] famous American and English writers and composers. They started to interview them. It was so touching when they interviewed Stravinsky. He was 90. He said – in Russian – ‘My teacher[Nikolai] Rimsky-Korsakov suffered from Russian censorship and that’s why I signed this letter, because these people protested against censorship’.”

The appeal didn’t keep Litvinov and his group out of prison, but it did have global political impact, opening a path between Litvinov and Spender. And it led to the creation of Index on Censorship. “Mary McCarthy said that the letter had more influence than napalm did in Vietnam,” he said proudly. “Our fight was a fight for freedom of speech, a protest against censorship. Censorship could be when they don’t let you publish a book, or when you lose a job, or when you get kicked out of the country, or when you get put in prison. All that means censorship.”

Just before the Red Square demonstration, Litvinov sent a letter to Spender suggesting an international council to support democracy in the Soviet Union, along with a publication to promote the situation there. “When I returned [from Siberia],there was a young man – now I realise that he was 10 years older than I, but he looked younger. He said: ‘I am Michael Scammell. I am a Russian specialist’.”

Scammell asked Litvinov if he knew more about what Scammell was doing now. “I said ‘No’,” he recalled, with a smile appearing after all these decades. Scammell said: “You gave me my first job. I was a writer and journalist. Now I have a job at a magazine as editor of Index on Censorship.” The idea that Litvinov had broached with Spender had come to fruition in his absence thanks to him, Stuart Hampshire, Scammell and others. “We became friends and Scammell was eventually kicked out of Russia,” Litvinov remembered.

Scammell organised lectures for Litvinov at British universities and invited him to join the Index editorial board, which he did for a while. I wonder whether Litvinov thought that repression could return to Russia after all this time. Indeed, today, he sees a direct line to what’s happening there. “It is a continuation of the kind of thing that happened with Russia and Czechoslovakia. Ukraine was [always]a threat to the Soviet empire. It was clear for all of us that if Ukraine would survive on its own there would be no more Soviet Union. So, there was always tension. In the Stalinist labour camps, half of the political prisoners in the Gulag after World War I were Ukrainian… people strongly felt their national identity and culture. A lot of dissidents became our friends.” But he didn’t consider war. “I really didn’t expect it until the last minute. Russia really has to lose badly or Russia will start another imperialist adventure,” he said.

I wonder, too, about his assessment of Vladimir Putin. He is quick to respond. “In the 1930s, there were very terrible KGB people but among them there were at least people who were ideological communists. In Putin’s generation they didn’t believe in communism or Marxism. They believed in secret police and dirty tricks and spying.” He describes his surprise at how so many people find Putin palatable. “I always thought that because he was KGB, he was bad. He said he was proud of the KGB. The KGB executed millions of people and he is still proud. If he would say they did some good things and some bad things… but nothing.”

In 2006 he retired from his 30-year job as a science teacher at a Westchester school and today he stays in close touch with those who have left, and continue to leave, Russia. He does what he can to support dissent inside the country, especially backing a new generation with fundraising and encouragement. “There is a group to whom I am very close – OVD-Info. The guy who started it is in Germany and they are available 24/7. If someone is arrested anywhere in Russia, they can call them and, in an hour, there will be a lawyer at the police station. They are the next generation of dissidents.”

Does Litvinov have any regrets, having performed heroic actions that exiled him from his birth country? “This was the whole fun of it,” he said. “I enjoyed my life. I was not afraid. I was ready for much worse conditions than I had in Siberia. Then I emigrated and saw America and Europe. I feel like I am more American than Russian.”

Before leaving, I ask him if he has hope. He sighs and at first responds: “Oh, hope.” I think he will say “No”, but instead he says: “Now, with the war, strangely enough there is more hope. Because it looked like Putin had a good chance, he had so much control, but now because of the crazy war that makes no sense, he probably won’t survive for long. What will happen I don’t know. [But] I think the war will kick him out. If the war is over, practically Russia cannot win.

This article is from the winter issue of Index on Censorship, which will be published shortly. Click here more information on the issue.

2 Sep 2022 | Opinion, Russia, Ruth's blog

Mikhail Gorbachev in 2008. The former president of the Soviet Union passed away on 30 August. Credit: European Parliament

In every field there are people who become living legends, people who inspire their colleagues and shape their chosen field. They add to our collective knowledge, they shape the world we live in and their contributions ensure that we both question the status-quo and think again about our individual and collective core values.

Sometimes these people reach further than their own fields. Sometimes they inspire or challenge the world. Whether as thinkers, writers or leaders. Sometimes their experiences and their contributions come to define an era of history – for some maybe even just one year.

1989. A year of deep turmoil. A year that reshaped the world. A year that defined the next generation. A year of both hope and horror. And on a personal level, a year that defined the type of world that I was going to live in.

1989 saw the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Tiananmen Square protests, the Velvet Revolution, the Hillsborough disaster, the Exxon Valdez spill, Solidarity was elected in Poland, FW de Klerk was elected in South Africa, Sky TV was launched and the Ayatollah Khomeini issued a fatwa against Salman Rushdie. In different ways each of these events shaped the world we live in today – 33 years later.

I often write that there has been too much news. Too many issues for the Index team to cover. Too many crises. In 1989 we published nine editions of the magazine, to keep up with the news and to ensure that voices of dissidents were being heard, as authoritarian regimes began to fall.

In the last month I have found myself thinking a great deal about the events of 1989 and what they led to. The path of history that was chosen on those pivotal days and the actions of our leaders whose immediate responses to these events had long-term consequences. Whilst there are many global figures who dominated the news during my childhood, two of them have this month caused me to pause and consider what the world would have been like if they hadn’t been brave enough to challenge the status quo.

Sir Salman Rushdie and Mikhail Gorbachev.

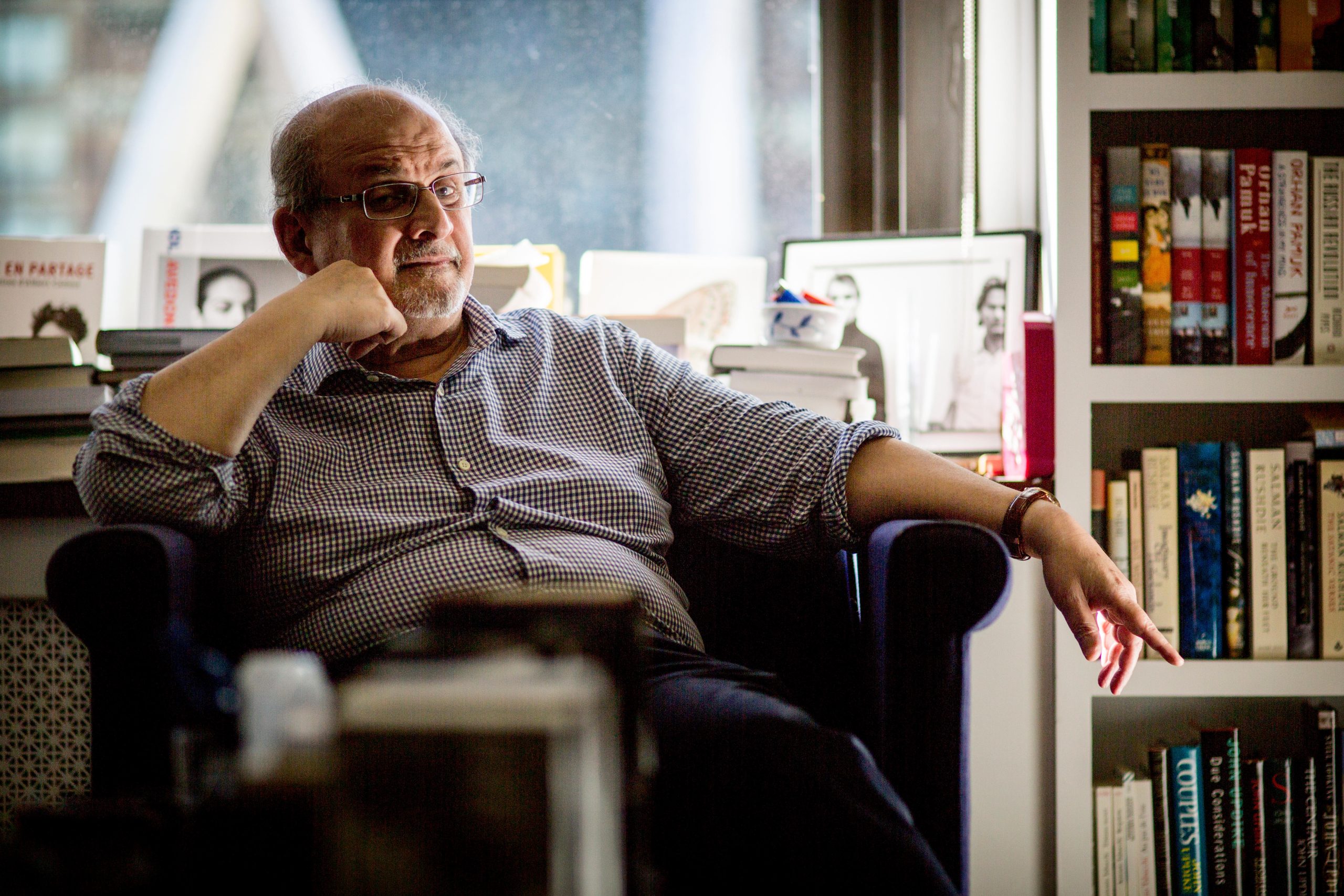

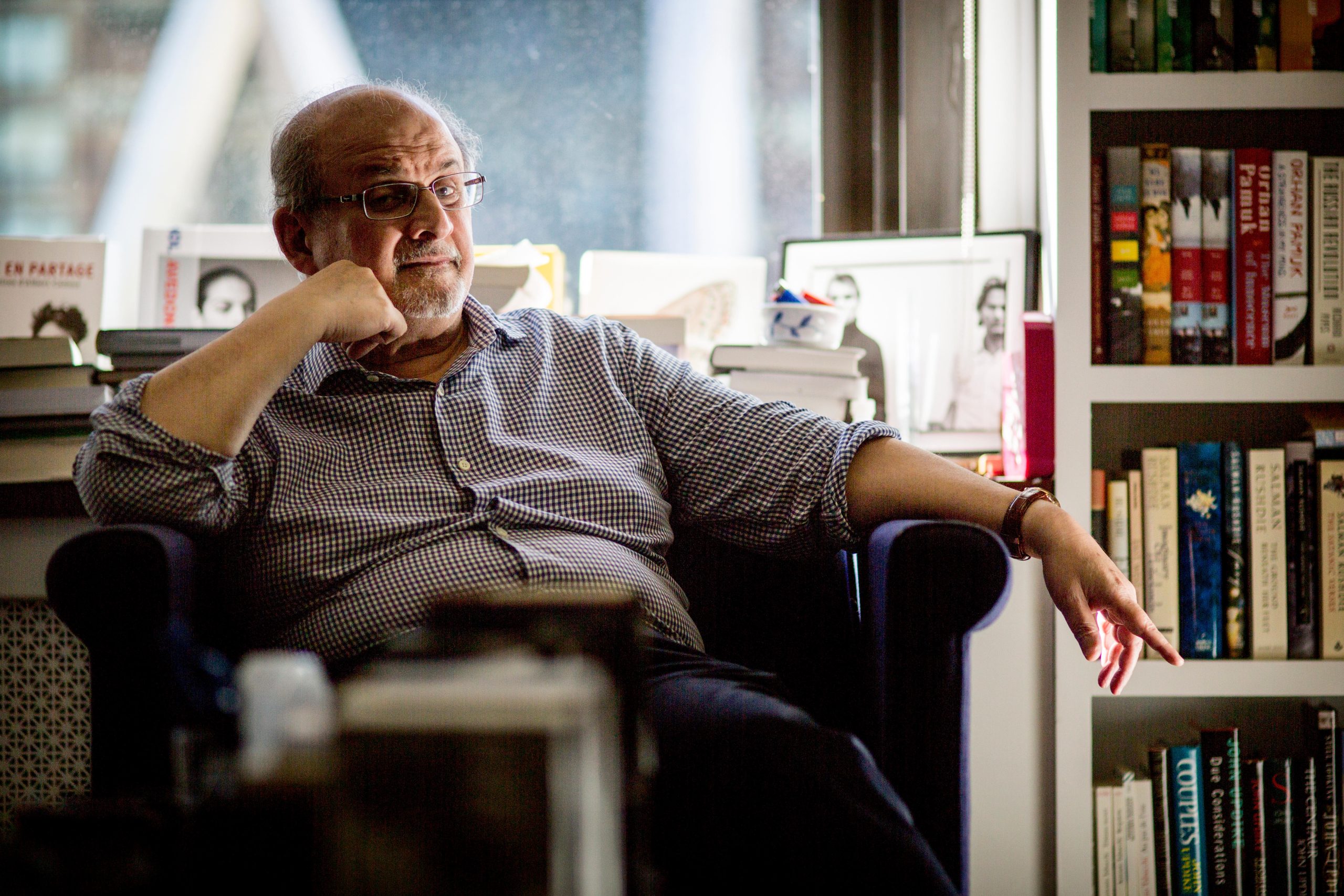

Salman Rushdie pictured in New York in 2016. Credit: Orjan Ellingvag/Alamy

Every day since the horrendous attack on Sir Salman, last month, Index has received messages of support for him as he recovers from his injuries. The messages have been touching, political and occasionally controversial – just like his writings! What they have demonstrated is regardless of people’s associations with him and their feelings towards him, his bravery and commitment to the values of freedom of expression in the face of the gravest of threats inspired a generation.

For over three decades he has refused to be intimidated, to be cowed. He continued to write, to speak and stay true to his values. He embodies the fight of the dissident, the determination to be heard and the power of words. He has shaped my approach to the world we live in and more importantly he has provided a role model for all of those that Index seeks to support and promote every day. I am so pleased that those who sought to assassinate him failed and we still have him amongst us.

In a different way Mikhail Gorbachev is just as fundamental to the history of Index. I’m not sure that Michael Scammell, the first editor of Index, would have believed that within a decade of Gorbachev’s coming to power in the USSR his writing would be in Index. His bravery in embracing glasnost provided hope for a generation.

The fall of the Berlin Wall without military repercussions provided hope of a peaceful transition to democracy – not just in central and eastern Europe but throughout the world.

This isn’t to say he wasn’t flawed. He was and his actions in the Baltics and the Caucuses were as expected from an authoritarian leader, and his support for the 2014 annexation of Crimea will forever tarnish his legacy.

But… Index was founded to provide a platform for samizdat, to provide a voice for dissidents who lived behind the Iron Curtain, to campaign for the right to freedom of expression both in the USSR and around the world. His bravery in embracing glasnost provided space for people to speak freely, to write and to be heard, even if Putin once again has shut the door. Gorbachev enabled people to get a taste of what they were missing. We can only hope that in the long arch of history glasnost will win out.

14 Apr 2022 | News and features, Russia, Volume 51.01 Spring 2022, Volume 51.01 Spring 2022 Extras

The story of Index on Censorship is steeped in the romance and myth of the Cold War.

In one version of the narrative, it is a tale that brings together courageous young dissidents battling a totalitarian regime and liberal Western intellectuals desperate to help – both groups united in their respect for enlightenment values.

In another, it is just one colourful episode in a fight to the death between two superpower ideologies, where the world of letters found itself at the centre of a propaganda war.

Both versions are true.

It is undeniably the case that Index was founded during the Cold War by a group of intellectuals blooded in cultural diplomacy. Western governments (and intelligence services) were keen to demonstrate that the life of the mind could truly flourish only where Western values of democracy and free speech held sway.

But in all the words written over the years about how Index came to be, it is important not to forget the people at the heart of it all: the dissidents themselves, living the daily reality of censorship, repression and potential death.

The story really began not in 1972, with the first publication of this magazine, but with a letter to The Times and the French paper Le Monde on 13 January 1968. This Appeal to World Public Opinion was signed by Larisa Bogoraz Daniel, a veteran dissident, and Pavel Litvinov, a young physics teacher who had been drawn into the fragile opposition movement during the celebrated show-trial of intellectuals Andrei Sinyavsky and Yuli Daniel (Larisa’s husband) in February 1966. This is now generally accepted as being the beginning of the modern Soviet dissident movement.

The letter itself was written in response to the Trial of Four in January 1968, which saw two students, Yuri Galanskov and Alexander Ginzburg, sentenced to five years’ hard labour for the production of anti-communist literature.

The other two defendants were Alexey Dobrovolsky, who pleaded guilty and co-operated with the prosecution, and a typist, Vera Lashkova.

Ginzburg later became a prominent dissident and lived in exile in Paris, Galanskov died in a labour camp in 1972 and Dobrovolsky was sent to a psychiatric hospital. Lashkova’s fate is unclear.

The letter was the first of its kind, appealing to the Soviet people and the outside world rather than directly to the authorities. “We appeal to everyone in whom conscience is alive and who has sufficient courage… Citizens of our country, this trial is a stain on the honour of our state and on the conscience of every one of us.”

The letter went on to evoke the shadow of Joseph Stalin’s show-trials in the 1930s and ended: “We pass this appeal to the Western progressive press and ask for it to be published and broadcast by radio as soon as possible – we are not sending this request to Soviet newspapers because that is hopeless.”

The trial took place in a courthouse packed with Kremlin supporters, while protesters outside endured temperatures of 50 degrees below zero.

The poet Stephen Spender responded to the letter by organising a telegram of support from 16 prominent artists and intellectuals, including philosopher Bertrand Russell, poet WH Auden, composer Igor Stravinsky and novelists JB Priestley and Mary McCarthy.

It took eight months for Litvinov to respond, as he had heard the words of support only on the radio and was waiting for the official telegram to arrive. It never did.

On 8 August 1968, the young dissident outlined a bold plan for support in the West for what he called “the democratic movement in the USSR”. He proposed a committee made up of “universally respected progressive writers, scholars, artists and public personalities” to be taken not just from the USA and western Europe but also from Latin America, Asia, Africa and, ultimately, from the Soviet bloc itself. Litvinov later wrote an account in Index explaining how he had typed the letter and given it to Dutch journalist and human rights activist Karel van Het Reve, who smuggled it out of the country to Amsterdam the next day. Two weeks later, Soviet tanks rolled into Czechoslovakia to crush the Prague Spring.

On 25 August 1968, Litvinov and Bogoraz Daniel joined six others in Red Square to demonstrate against the invasion. It was an extraordinary act of courage. They sat down and unfurled homemade banners with slogans that included “We are Losing Our Friends”, “Long Live a Free and Independent Czechoslovakia”, “Shame on Occupiers!” and “For Your Freedom and Ours”.

The activists were immediately arrested and most received sentences of prison or exile, while two were sent to psychiatric hospitals.

Vaclav Havel, the dissident playwright and first president of the Czech Republic, later said in a Novaya Gazeta article: “For the citizens of Czechoslovakia, these people became the conscience of the Soviet Union, whose leadership without hesitation undertook a despicable military attack on a sovereign state and ally.”

When Ginzburg died in 2002, novelist Zinovy Zinik used his Guardian obituary to sound a note of caution. Ginzburg, he wrote, was “a nostalgic figure of modern times, part of the Western myth of the Russia of the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s, when literature, the word, played a crucial part in political change”.

Speaking 20 years later, Zinik told Index he did not even like the English word “dissident”, which failed to capture the true complexity of the opposition to the Soviet regime. “The Russian word used before ‘dissidents’ invaded the language was ‘inakomyslyashchiye’ – it is an archaic word but was adopted into conversational vocabulary. The correct translation would be ‘holders of heterodox views’.”

It’s perhaps understandable that the archaic Russian word didn’t catch on, but his point is instructive.

As Zinik warned, it is all too easy to romanticise this era and see it through a Western lens. The Appeal to World Public Opinion was not important because it led to the founding of Index. The letter was important because it internationalised the struggle of the Soviet dissident movement.

As Litvinov later wrote in Index: “Only a few people understood at the time that these individual protests were becoming a part of a movement which the Soviet authorities would never be able to eradicate.” Index was a consequence of Litvinov’s appeal; it was not the point of the exercise and there was no mention of a magazine in the early correspondence.

The original idea was to set up an organisation, Writers and Scholars International, to give support to the dissidents. It was only with the appointment of Michael Scammell in 1971 that the idea emerged to establish a magazine to publish and promote the work of dissidents around the world.

Spender and his great friend and co-collaborator, the Oxford philosopher Stuart Hampshire, were still reeling from revelations about CIA funding of their previous magazine, Encounter.

“I knew that [they]… had attempted unsuccessfully to start a new magazine and I felt that they would support something in the publishing line,” Scammell wrote in Index in 1981.

Speaking recently from his home in New York, Scammell told me: “I understood Pavel Litvinov’s leanings here. He understood that a magazine that was impartial would stand a better chance of making an impression in the Soviet Union than if it could just be waved away as another CIA project.”

Philip Spender, the poet’s nephew, who worked for many years at Index, agreed: “Pavel Litvinov was the seed from which Index grew… He always said it shouldn’t be anti-communist or anti-Soviet. The point wasn’t this or that ideology. Index was never pro any ideology.”

It has been suggested that Index did not mark quite such a clean break – it was set up by the same Cold Warriors and susceptible to the same CIA influence. In her exhaustive examination of the cultural Cold War, Who Paid the Piper, journalist Frances Stonor Saunders claimed Index was set up with a “substantial grant” from the Ford Foundation, which had long been linked to the CIA.

In fact, the Ford funding came later, but it lasted for two decades and raises serious questions about what its backers thought Index was for.

Scammell now recognises that the CIA was playing a sophisticated game at the time. “On one level this is probably heresy to say so, but one must applaud the skills of the CIA. I mean, they had that money all over the place. So, I would get the Ford Foundation grant, let’s say, and it never ever occurred to me that that money itself might have come from the CIA.”

He added: “I would not have taken any money that was labelled CIA, but I think they were incredibly smart.”

By the time the magazine appeared in spring 1972, it had come a long way from its origins in the Soviet opposition movement. It did reproduce two short works by Alexander Solzhenitsyn and poetry by dissident Natalya Gorbanevskaya (a participant in the 1968 Red Square demonstration, who had been released from a psychiatric hospital in February of that year). But it also contained pieces about Bangladesh, Brazil, Greece, Portugal and Yugoslavia.

Philip Spender said it was important to understand the context of the times: “There was a lot of repression in the world in the early ’70s. There was the imprisonment of writers in the Soviet Union, but also Greece, Spain and Portugal. There was also apartheid. There was a coup in Chile in 1973, which rounded up dissidents. Brazil was not a friendly place.”

He said Index thought of itself as the literary version of Amnesty International. “It wasn’t a political stance, it was a non-political stance against the use of force.”

The first edition of the magazine opened with an essay by Stephen Spender, With Concern for Those Not Free. He asked each reader of the article to say to themselves: “If a writer whose works are banned wishes to be published and if I am in a position to help him to be published, then to refuse to give help is for me to support censorship.”

He ended the essay in the hope that Index would act as part of an answer to the appeal “from those who are censored, banned or imprisoned to consider their case as our own”.

Since Index was founded, the Berlin Wall has fallen and apartheid has been dismantled. We have witnessed the “war on terror”, the rise of Russian president Vladimir Putin and the emergence of China as a world superpower.

And yet, if it is not too grand or presumptuous, the role of the magazine remains unchanged – to consider the case of the dissident writer as our own.