7 Apr 2010 | Events, Uncategorized

April 10th 2010 11am – 6pm

A day of discussion to accompany the premiere run of Gurpreet Kaur Bhatti’s new play Behud at the Belgrade Theatre, Coventry

‘Behzti Five Years on’ – panel discussion

Chaired by Kenan Malik (writer, broadcaster), author of From Fatwa to Jihad.

Panellists: Giles Croft (Nottingham Playhouse); Hamish Glen (Belgrade Theatre), Sunny Hundal (Asians in the Media, liberalconspiracy.org), Trina Jones (Birmingham Rep), Hardish Virk (Multi Nation Arts).

In 2004 there were concerns that the fallout from the ‘Behzti’ affair would have a chilling effect on British theatre and that it would become increasingly difficult to stage controversial work. ‘Behzti Five Years On’ focuses on theatre in the Midlands, asking to what extent this has come true. Theatre has a distinct role in reflecting contemporary society, and in influencing, shaping, and interrogating our shared culture. Are we witnessing a trend towards subtle forms of censorship, underpinned by the government’s national security agenda? Is support for freedom of expression on the decline?

The panel discussion will be followed by lunch and the matinée performance of Behud by Gurpreet Kaur Bhatti. We will then have an after-show discussion with Lisa Goldman, Hamish Glen and members of the cast, chaired by Jo Glanville (editor of Index on Censorship).

The discussion events are free and the matinee performance is priced as on theatre website . For those who wish to attend the whole day we are offering a ticket priced £20, £10 concession to cover a light lunch, refreshments and the matinee performance. Call 024 7655 3055 to book tickets.

Behud (Beyond Belief) is also running in London’s Soho Theatre, from 13 April to 8 May, 2010. Book online here.

For more information please visit http://art.indexoncensorship.org

8 Jan 2005 | Art and the Law Reports, Artistic Freedom Commentary and Reports

By Ben Payne, Associate Director (Literary) Birmingham Rep

Background

In December of 2004, Birmingham Repertory Theatre staged the world premiere of Behzti, a new play by Gurpreet Kaur Bhatti, in the smaller of its two theatres, The Door, which is a space exclusively dedicated to the production and presentation of new plays. “Behzti” is a word in common usage amongst the Punjabi speaking community meaning “dishonour” or “shame”.

Behzti tells the story of Balbir, an elderly Punjabi Sikh woman and her daughter, Min, who has devoted her life to the care of sickly mother. Balbir’s determination to secure Min’s future leads her to make an uncharacteristic visit to the local Gurdwara (Sikh temple) to see the influential Mr. Sandhu whom she hopes can arrange a suitable marriage for Min. This is in defiance of the fact that their community have ostracised both of them because of the shame brought on the family by the suicide of Balbir’s husband, Tej, years before. When the real reason behind Tej’s demise is revealed, Mr Sandhu rapes Min, leading to a cover-up. Finally, Balbir and another of Mr Sandhu’s victims, Teetee, take revenge by murdering Mr Sandhu, leaving Min with one hope of a way out: Elvis, Balbir’s nurse, an Afro-Caribbean boy who has loved her all along …

Following a three-month dialogue with some leaders of the Sikh community in Birmingham about the production of the play, performances of Behzti met with mostly peaceful protests from its first night to the night of Saturday 18th December. That night, a small number of the 400 demonstrators turned violent, breaking into the theatre and smashing windows, doors and equipment. On Monday 20th December, the theatre decided to cancel the remaining 7 performances of the show when assurances were not given that these incidents would not be

repeated or escalated. The writer was forced to go into hiding and received police protection after death-threats were made against her and the controversy around both the play’s production and its cancellation ran in the media for several weeks afterwards.

Subsequently, Christian Voice, a religious pressure group explicitly used the example of the protests against Behzti as an example in its campaign to make the BBC cancel its television broadcast of the National Theatre’s production of Jerry Springer: The Opera. The BBC

received a record number of complaints about this broadcast but nevertheless went ahead with the transmission of the programme on 8th January.

Both events took place in the context of the progress of a proposed new law through the UK Parliament banning “incitement to religious hatred” which some British artists and campaigning groups believe could be used to prevent similarly controversial works of art from being seen or made in the future.

The following was written a couple of weeks after the events of Saturday 18th.

Behzti

Some writers have both the peculiar ability and the courage to tell stories that express what is being thought but not being said. Gurpreet’s first play Behsharam (Shameless) staged by the Rep in 2001 was about two Asian sisters, Sati and Jaspal, whose family’s attempts to appear outwardly normal render them quite abnormal. Behzti (Dishonour), her second, took an ambitious leap into something bigger and broader. Of course, she couldn’t have predicted how it would end up as a touchstone for issues bigger still. For Behzti is now not just a play, but a “controversy”, part of debates wider than could ever be encompassed by one piece of theatre: between artistic freedom and religious sensibilities; the proposed law against incitement to religious hatred; the status of women within minority communities; not least, whether a theatre should put artistic principle before the safety of its audiences and employees.

It is one of a number of ironies about the whole affair that had the demonstrations on the evening of Saturday 18th December remained peaceful and the play had continued for the final seven performances of its three-week run, none of this would have happened. This would have been one new play at a small studio theatre that attracted some protests. Those

who attempted to suppress it, a small minority violently only succeeded in giving the play’s wider implications further resonance.

Most of this controversy is actually undeserved because much of the way the play has been described is inaccurate. Unless you regard kissing as particularly depraved, the play does not “depict scenes of sexual violence and depravity” – a phrase, which, with minor variations, has been passed around unquestioned in the media since. The rapist in the play is not a priest. A rape and a murder are part of the plot but neither act is seen. This may offer little comfort to those who believe that to even imply such things could take place within the bounds of a place of worship is wrong. Nevertheless, it is important to be accurate if only to show that the playwright was never gratuitous. Only those who chose to drum up the play’s supposed offensiveness, not having seen or read it, could be accused of that.

There is a heavy onus on a playwright to be as responsible and balanced as any journalist. This weight may be greater still for non-white playwrights whose opportunities to see their plays staged remain limited. If your community has barely been seen on stage before, the pressure to show every perspective and point of view can be overwhelming. For another British Asian writer whose play the Rep produced, it partly contributed to a physical breakdown that required hospitalisation the night before rehearsals started. The fear of how your community might react to you – or your family – can act as a form of censorship far more subtle and efficient than smashing up a theatre – simply because the play never gets written in the first place. But maybe smashing up a theatre will do. For where then do writers confront their fears? Where do those fears actually become the point where they start writing?

For Gurpreet, one starting point is satire and, although satirists are comics, they operate from a position of moral outrage, no matter how heavily disguised in humour this is. The second scene of Behzti starts with two ladies of the Gurdwara, Polly Dhodar and Teetee Parmar, rifling the temple shoe-racks for designer labels. Perhaps in a community based on principles of equality and modesty, these abuses seem more glaring. Perhaps too the critique of the gap between principles and practice is more penetrating. But just because a play suggests bad things can happen in a sacred place, does not make it an irreligious play. And just because a writer shows characters behaving immorally, does not make it immoral. On the contrary, Behzti is a very moral; very angry that explores the reasons why some people don’t live up to their principles. And here is another irony: the anger of the writer and the anger of the protestors is, in fact, the same. They are angry about the same abuses. It’s just that she chose to express her anger in a play, whereas they chose to direct their anger at her.

Whilst being a satirist, she also shows huge compassion for her characters. Mr Sandhu, the Chairman of the Gurdwara’s Renovation Committee is a rapist. But he is also a man who senses that his entire life has been wasted. As he tells Min, the heroine:-

“After a while we get used to the disappointment. We don’t even have to live with it because we pass our failures on to you, our children. And then it becomes your problem …”

This combination of satire and empathy can be unsettling. However, perhaps it also communicates a peculiar duality of experience that resonates for many of those audience members who have packed in to see either Behsharam or Behzthi, or both : a world where Qaawalis and the songs of Karen Carpenter collide; where the outcast can reveal huge resources of spirit; where the leaders and fathers you are supposed to look up to can sometimes let you down; where nothing, in fact, is quite what it might want to appear to be …

Admittedly then, this was never a story that was going to have those leaders jumping for joy. But that’s all it is – a story. It cannot represent an entire faith or community even if that was its aim. Yet so much of the debate (where it has actually been about the play at all) has been about representations, images and settings, rather than what its story might tell us.

Was the theatre wrong to involve itself in any kind of dialogue with representatives of the Sikh community in the lead-up to the production? Would the outcome have been any different either way? Whatever the case, it’s important to stress what the purpose of that dialogue was. For the theatre, it was about being transparent about the play, the issues that it raised and to ensure that its production was seen in context. It failed. But not to make this attempt would have surely suggested that theatre was blasé, or that it had something to hide. For some of those we talked to, it became about trying to change the play to make it more “acceptable” to them. That failed too. For some, the setting of part of it in a Gurdwara was unacceptable. Yet the argument that this setting had to be changed, whilst insisting this would not fundamentally change the meaning of the play was, to the theatre, equally unacceptable. For some others, homosexuality was unacceptable; to show a Sikh girl in love with an Afro-Caribbean boy, that too, was unacceptable – to some …

Birmingham justly prides itself on the degree to which it has integrated different faiths and communities and the uses it has made of culture in its regeneration as a city. What this controversy might suggest is that there are fault-lines beneath these achievements: that there can be misunderstandings and received ideas that exist on all sides, across communities and within them, between the liberal artistic community and faith-based communities, between white and non-white, between one generation and another – about identity and representation; about the different functions of art and the roles of the artist …

Undeniably, and like most other theatres and theatre companies in this country, the Rep is run by white people. But for the last 20 years, the company has worked consistently with established British Asian theatre companies like Tara Arts and Tamasha and with the newer ones like Kali and Firebrand, co-producing and presenting a wide range of work. And from the Rep’s own main stage adaptation of the Indian epic, The Ramayana to a play like Ray Grewal’s comedy My Dad’s Corner Shop which toured local schools and community venues, the Rep has also produced an equally wide range of its own work created by Asian artists. Diversity is not only about the cultural background of those who run our theatres, nor just about the artists who create the work for them, but about the even greater diversity of styles, subject matter and perspectives that can and should flourish within them.

On the other hand, if tolerance and understanding means only accepting the bland and celebratory, never putting on the play that might be unacceptable to some people, this is neither real tolerance or understanding, nor real diversity. And from here it is easy to teeter over into the recriminatory and irrational. Just prior to the opening performance of Behzti, Gurpreet was directly and personally denounced as a “backstabber”, “sick” and “mentally disturbed” by a group of men that included a Birmingham city councillor.

Such abuse would have been more than enough reason to continue with the show, come what may, and the theatre has been criticised for its final decision to cancel the remaining performances after the violent protests of the Saturday. It could be argued that it would have been possible to continue, perhaps, if Behzti had been produced at a different time, secondly, if the architecture of the building had been different …

As the front of the theatre is almost entirely glass, it makes it spectacularly vulnerable to this sort of attack – an event the original designers probably didn’t plan for. As well as smashing these windows and doors, some protestors broke in through the stage door, destroying equipment. The actors for both shows then had to lock themselves in their own dressing rooms until order was restored. Similarly, when it happened, 800 people, including many children seeing the show in the Main House theatre, were trapped in the foyer and on the floors above. The only way to evacuate them was back out into the public space occupied by both the demonstrators and people visiting Christmas attractions on Centenary Square. On the Monday morning, the theatre sought assurances from the protest leaders that these violent events would not be repeated. These were not given – perhaps they could not be – and the implication was that things would escalate. A representative from Equity, the actors’ union, came to the theatre the same morning. Even had the management decided to go ahead nevertheless, the acting company would probably have been advised not to. Finally,

no one, the playwright least of all, was prepared to see another person injured – or possibly killed – for the sake of her play.

Nevertheless, the decision to stop the show breached a fundamental principle. Common sense did not prevail, violence did, and a work of art was censored as a result. We have a duty as a theatre to continue the debate that this event provokes because it raises issues crucial to the future cultural – even political – health of the country. The subsequent controversy around the broadcast of Jerry Springer – The Opera shows it is misguided to hope that these questions will just go away, not least because there will be more young writers who are going to say difficult and challenging things and who deserve to have their voices heard. The fact that Behzti – the play – ultimately shows that some people would rather that the individual dissenting voice was silenced, and by violent means if necessary, is the final irony of what happened.

Just before the play’s opening performance, Gurpreet bumped into Mr Sewa Singh Mandla, a 77-year-old Sikh community leader who had been part of the representations to the theatre about the production. Mr Mandla took the opportunity to apologise for the insults that had been thrown at her by others shortly before. To which Gurpreet answered: –

“You feel passionately about what you believe. And I feel passionately about what I believe. We’re not going to agree … and you know what? That’s ok …”

And, as Mr Mandla himself signed off in a later letter, “It is healthier to agree to disagree.” Amen to that.

14 Aug 2018 | Artistic Freedom, News and features, United Kingdom

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

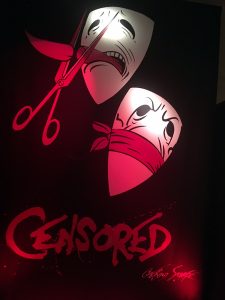

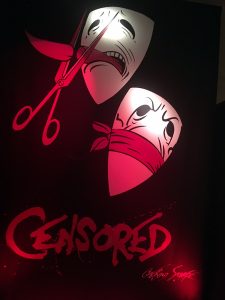

Censored by George Scarfe

Marking the 50th anniversary of the end of 300 years of theatre censorship, the Victoria and Albert Museum’s exhibition explores how restrictions on expression have changed.

The Theatres Act 1968 swept away the office of the Lord Chamberlain, which had the final say on what could appear on British stages.

“The 1968 Theatres Act was one of several landmark pieces of legislation in the 1960s, including the end of capital punishment, the legalisation of abortion, the introduction of pill, and the decriminalisation of homosexuality (for consenting males over the age of 21),” Harriet Reed, assistant curator at the V&A said.

Plays that had the potential to create immoral or anti-government feelings were banned by the Lord Chamberlain’s office or ordered to be edited. The exhibition includes original manuscripts with notes on what needs to be changed and letters from Lord Chamberlain explaining why the edits are required.

In the exhibition there are several pieces including a manuscript about the play Saved by Edward Bond. The play tells the story of a group of young people living in poverty and includes a scene in which a baby is stoned to death.

“When the Royal Court Theatre submitted the play to the censor, over 50 amendments were requested. Bond refused to cut two key scenes, stating ‘it was either the censor or me – and it was going to be the censor’. As a result, the play was banned,” Reed said.

Before the act was passed, playwrights got around the law by staging banned plays in “members clubs” which meant they could not be persecuted since it was private venue.

“The continued success of this strategy and the reluctance to prosecute made a mockery of the Lord Chamberlain’s powers and reflected the increasingly relaxed attitudes of the public towards ‘shocking’ material.

“The first night after the Act was introduced, the rock musical Hair opened on Shaftesbury Avenue in the West End. It featured drugs, anti-war messages and brief nudity, ushering in a new age of British theatre,” Reed said.

The exhibition changes from showcasing plays that were censored by the state to art, plays, movies, and music that are censored by society as a whole.

“It could be argued that a mixture of government intervention, funding/subsidy withdrawals, local authority and police intervention, self-censorship, and public protest now regulates what is seen on our stages,” she said.

Behzti, a play, and Exhibit B, a performance piece, were cancelled after protests by the public. The creators of both pieces were advised by the police to cancel their plays for health and safety reasons related to protests over the content.

Similarly, Homegrown, a play about radicalisation created by Muslims was shut down by the National Youth Theatre. The play was later published and a public reading was held.

On video, people involved in the UK arts industry such as Lyn Gardner, a theatre critic and Ian Christie, a film historian comment on what they believe to be censorship today. They cite art institutions that refuse to exhibit controversial material for fear of losing funding or facing public uproar. Julia Farrington, associate arts producer at Index on Censorship and one of the participants, calls this the “censorship of omission.”

The exhibition is capped by a piece by George Scarfe. The piece, the last work that attendees see, is a painting of two white masks on black cloth. The first one which is slightly higher and to the right of the second has it red tongue sticking out with the tip severed by a red scissors. The second one has a red cloth tied around it mouth. The word Censored is written in red and all caps below the two masks.

The painting is bold and the image of the tongue being cut off by scissors creates a “visceral” feeling. It depicts the two types of censorship that people now face– either talk and be violently censored or self-censor and never be heard.

“Many people would say that we are freer to express ourselves than ever before – with the boom of social media, we are able to communicate our thoughts and opinions on an unprecedented scale. This can also, however, invite more stringent and aggressive censorship from either the platform provider or under fear of criticism from other users,” Reed said.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

Index encourages an environment in which artists and arts organisations can challenge the status quo, speak out on sensitive issues and tackle taboos.

Index currently runs workshops in the UK, publishes case studies about artistic censorship, and has produced guidance for artists on laws related to artistic freedom in England and Wales.

Learn more about our work defending artistic freedom.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1534246236330-00e1ebeb-95f3-4″ taxonomies=”15469″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

19 Jun 2018 | Artistic Freedom, News and features, Risks, Rights and Reputations

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”100614″ img_size=”full”][vc_column_text]Artists make the work. Institutions put the work on. That’s the deal. It’s a simple but weird relationship. The art would probably still live without the institution but the latter could not exist without the art. Still the institution is charged with incredible power – to commission, to programme, to bring the art into the public psyche. And when the work is threatened, power over it is in the hands of the institution.

The moment the threat comes is difficult to describe. Charged, surreal, heart beating fast. Not knowing where this is going to land or end. Will there be violence, humiliation, cuts to funding? A variety of narratives emerge. It’s difficult, for everyone. I’ve had a few brushes with controversy. I understand the pain and loss which occurs when the work is halted and I’ve seen how tough it is for good people in institutions under pressure, trying to do the right thing, unsupported and cornered. They can too easily become malleable. Fear takes hold, they cave in and the work is withdrawn. And something dies in everyone.

In 2004, after protests against my play Behzti (Dishonour) turned violent, the Birmingham Rep cancelled the run following police advice. The theatre’s position was immediately attacked by artists and cultural institutions, however politicians remained silent. One Home Office minister, possibly mindful of the large Sikh population in her constituency, remarked that the theatre had thankfully come to the right decision. The clear message from the police and government was that security was paramount and must override freedom of expression.

In 2010 my play Behud (Beyond Belief), was produced by Soho Theatre and Coventry Belgrade. There were rumours about protests. Before the dress rehearsal, a bombshell landed, the police asked the theatres to pull the play. This seemed to be based on no intelligence, merely the fear that something may happen. The theatres refused and the play went on without incident, but once more security was used as an excuse to curtail art.

In 2013, I was asked to remove some lines, which had previously been cleared, from a radio play for the BBC. My producer stood her ground, but was ultimately told if she kept the lines in, we were on our own.

Artists must have the freedom to explore the extremities of their imagination to provoke and poke around amidst the dirt and filth of the human condition. If not, art becomes sanitised and homogenous because it is only borne of fear. A corrosive fear that is the enemy of creativity.

[/vc_column_text][vc_separator][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”96548″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/campaigns/artistic-freedom/rights-risks-and-reputations-challenging-a-risk-averse-culture/”][vc_column_text]

This article is part of Risks, Rights and Reputations, an ongoing series of Index on Censorship workshops and articles challenging our increasingly risk averse culture.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”100617″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2018/06/elephant-protecting-far-right-what-about-our-rights/”][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][vc_column_text]I’ve seen a real lack of consistency around freedom of expression. Decisions made when work is under threat are too dependent on the character of the leadership team and the support and advice they have access to. And sometimes pre-emptive fears mean that work doesn’t even get commissioned or happen in the first place.

Freedom of expression must be at the core of artistic institutions, and the concept of free thinking, cherished and celebrated. This has to come from the top – board and CEO level, if it is to filter down. Artists are by nature mavericks and it’s essential that leaders of institutions do not lose identification with that independent spirit which must also exist within them.

When challenge or threat happens, it is often from leftfield, so organisations are unprepared and taken by surprise. Institutions can help themselves by believing in the work in the first place. So that once something is commissioned or programmed they regard themselves as part of that provocation. This wholehearted commitment to the work might help them to summon the same courage demanded of the artist.

Other agencies such as the police, lawmakers, local authorities pile in pretty quickly when controversy strikes. If artistic institutions, well intentioned but incoherent, fail to make their case, it’s all too easy to stop the art. So it’s really important to spell out what we do and why we do it, because not everyone gets it. Security trumps freedom of expression far too quickly, often before the facts are completely known or understood, because other agencies take their jobs seriously. They, quite rightly, fight their corners and we must fight ours.

There is also the question of why challenge occurs in the first place. Everyone, I believe has the right to protest and express offence. When this turns into calling for the work to be halted, it’s a different matter. I’d encourage institutions to look at their audiences, to consider how open and welcoming they are and honestly question if they are properly embedded into the communities they serve. We need a range of work which is authentic, challenging if it wants to be, and a culture amongst our institutions which encourages audiences to bear what is unbearable. Ask yourselves, where is the heartbeat of your organisation, is it reaching out, breaking new ground, scaring itself and you? This ambition has to come from our leaders who ultimately have control over the creative lens.

In order to support artists, institutions need clear strategies and policies otherwise freedom of expression is meaningless, relegated to nothing more than a woolly liberal idea. Start by integrating freedom of expression into your mission statement and make it clear to other agencies that it is a core value.

When and if work is stopped, the only way of filling the void is to create anew and keep one’s voice alive. As I write this, Elephant, my fourth play for the Birmingham Rep (who produced Behzti) is about to open. It’s a difficult piece about childhood sexual abuse, based on a true story. The production of Elephant is an example of an organisation leaping in with me. Being strong enough to put on a complex piece, and I believe, to have the will to take care of it and defend it if necessary.

Art’s function, after all, is not to maintain the status quo but to change the world. And some people are never going to want that to happen. Let’s remember, if the art is stopped, my silence is your silence too. And I promise you, when it comes, it’s devastating.

We need each other. So let’s be brave together.[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_custom_heading text=”Related articles” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]

When I started writing my third play, Behzti, in 2003 I could never have imagined the furore which was going to erupt. There was an atmosphere of great tension in the lead up to its production in December 2004, and it was indeed an extraordinary time. Mass demonstrations culminated in a riot outside the theatre.

In December of 2004, Birmingham Repertory Theatre staged the world premiere of Behzti, a new play by Gurpreet Kaur Bhatti, in the smaller of its two theatres, The Door, which is a space exclusively dedicated to the production and presentation of new plays. “Behzti” is a word in common usage amongst the Punjabi speaking community meaning “dishonour” or “shame”.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content_no_spaces”][vc_column][three_column_post title=”Risks, Rights and Reputations” full_width_heading=”true” category_id=”22244″][/vc_column][/vc_row]