16 Nov 2022 | BannedByBeijing, China, News and features

Twenty-three years after writing his best known work, Red Star Over China, Edgar Snow returned to China in 1960 to investigate claims that a radical agrarian reform programme had resulted in devastating famine. “I diligently searched, without success, for starving people or beggars to photograph … I do not believe there is famine in China,” Snow wrote.

Snow was wrong. The famine in China was both real and devastating. It is estimated as many as 30 million died in it. Snow’s bias lens had ghostly echoes with Walter Duranty’s reporting from Ukraine, during the Holodomor, the mass famines engineered by Stalin. Only when faced with overwhelming evidence did he eventually concede that the genocide occurred, “to put it brutally – you can’t make an omelette without breaking a few eggs” he said.

In information vacuums, common during times of conflict such as the civil conflict in Syria, as well as in areas controlled by authoritarian regimes, reporting from independent journalists can quickly define or redefine the public’s perception of a regime or situation. While journalists can play a powerful role in challenging censorship and propaganda from the state, they can also act as the state’s servants. Such was the case for both Snow and Duranty, whose rose-tinted views of the countries impacted global perceptions. Herein lies the point – those who claim to be independent reporters can be incredibly useful to the state, sometimes more so than those working within state media, because the notion that they are independent carries with it a level of authority and weight.

The use of “junket journalism” to obscure reporting on crimes against humanity has only grown in prominence and sophistication. Nowhere has this been more evident than in China where the government has co-opted a range of journalists and social media influencers to help strengthen the CCP’s control over its narrative and obscure legitimate scrutiny of a number of important issues, most notably the genocide of the Uyghur population. Recent party documents and officials have emphasised the need to bolster the CCP political line, and inject positivity into the CCP and China’s image. Current President Xi Jinping said, “Wherever the readers are, wherever the viewers are, that is where propaganda reports must extend their new tentacles”.

A recent International Federation of Journalists (IFJ) survey confirmed that “China is conducting a media outreach campaign in almost every continent” with the 31 developed and 27 developing countries that participated in the survey similarly targeted. The researchers told the Guardian, “China is also wooing journalists from around the world with all-expenses-paid tours and, perhaps most ambitiously of all, free graduate degrees in communication, training scores of foreign reporters each year to ‘tell China’s story well’”.

While many other countries, including established democracies, have sought to influence and shape independent reporting through tours, capacity building opportunities and other tactics, the CCP’s overt prioritisation of journalism that “depends upon a narrative discipline that precludes all but the party-approved version of events” raises significant concerns as to its intentions.

In this effort to shape global news, the CCP is advantaged by its huge pockets. It has spent around $6.6 billion since 2009 on strengthening its global media presence, supposedly investing over $2.8 billion alone in media and adverts. Sarah Cook, NED reporter and researcher, emphasised that “no country is immune”.

This ambition is best summarised by the Belt and Road News Network (BRNN), which includes 182 media organisations from 86 countries as members, and a Council, which includes 26 countries, including Spain, France, Russia, Netherlands and the UK. The launch of the BRNN was announced in a paid advertorial in The Telegraph produced by People’s Daily. In September 2019, BRNN hosted a workshop for international journalists in Beijing as part of the 70th anniversary celebrations of the People’s Republic of China, which was organised in partnership with the State Council Information Office of China. It included a visit to the offices of People’s Daily, Xinhua News Agency and other “central media units”, as well as trips to “Shaanxi, Zhejiang, Guizhou and Guangdong provinces for interviews and researches in order to personally experience China’s unremitting efforts and fruitful results in poverty alleviation, ecological civilization, big data industry, urban planning, and independent intellectual property rights.”

While the workshop was attended by representatives from 46 mainstream media outlets from 26 Latin American and African countries, it would be overly simplistic to suggest that China is only focusing on countries from the global south. Since 2009, the China-United States Exchange Foundation (CUSEF) has taken 127 US journalists from 40 US outlets to China. This foundation has been identified as working with China’s United Front as highlighted by US Senator Ted Cruz, in a letter to the President of the University of Texas at Austin, who stated that “[t]oday, CUSEF and the united front are the external face of the CCP’s internal authoritarianism”.

The IFJ report notes that “the Chinese Embassy has sought out journalists working for Islamic media, organising special media trips to showcase Xinjiang as a travel destination and an economic success story.” Xinjiang and the treatment of Uyghur communities is a prominent area in which the CCP has focused its efforts. After a visit to Xinjiang, Harald Brüning, author and director of the Macau Post Daily, stated that “the anti-China forces’ allegations of genocide are preposterous judging by what the Macao journalists, most of whom had not visited the region before, saw and heard in Xinjiang.” In his piece, Brüning did not disguise the genesis of his trip, exclaiming in the third paragraph “[t]he extraordinarily well-organised tour took place at the invitation of the Office of the Commissioner of the Foreign Ministry of the People’s Republic of China in the Macao Special Administrative Region.” The piece is heavily framed around rebutting existing reporting – labelled in the piece as lies – including the use of forced labour in the cotton fields of Xinjiang, as well as decrying the “brutality the religious extremists and separatists [have] resorted to”.

However an all-expenses paid junket does not guarantee full control of a journalist’s coverage. Olsi Jazexhi (below), a Muslim Canadian-Albanian journalist and historian sought a way to travel to Xinjiang because he was sceptical of the dominant narrative in the West that Muslims were being oppressed in China. He approached the Chinese embassy in Albania who invited him on a trip to Xinjiang with other “China-friendly journalists”. Once in Xinjiang, Jazexhi was shocked by the detainees’ testimonies of having been jailed for simple expressions of their religious identity, such as reading the Quran or encouraging others to pray. In Urumqi, he was lectured by state officials who equated Islam with terrorism and was shocked by the number of empty mosques or those repurposed into stores.

Olsi Jazexhi (right) listens to a handler during a tour of a mosque in Aksu city, Xinjiang in August 2019. Photo: Provided by Olsi Jazexhi

Other journalists who have tried to move away from the organised tours have faced a number of difficulties. When journalists have attempted to film camps that the government has not previously cleared for access, they have been turned away by local authorities. Road works or car crashes suddenly block their way and when the journalists attempt to return the next day, the roadworks suddenly reappear again. Members of a Reuters crew reported being tailed by a rotating cast of plain-clothed minders and “within an hour of the reporters leaving their hotel in the city of Kashgar through a back gate, barbed wire was erected across the exit and fire escapes on their floor were locked.”

While influencing journalists can sometimes be difficult, the expansion of blogging and social media influencing has opened up another avenue for state intervention. Travel vloggers who visit authoritarian countries say they just want to educate their viewers and avoid politics. Irish travel vlogger Janet Newenham told Al Jazeera after a controversial visit to Syria that “every country deserves to be shown in a different way and in a positive light even if most stuff about there has always been negative”. However, what can seem innocuous can take on more explicit political implications. “A lot of these vloggers are saying they’re apolitical in this and I’m sure that they are but the issue is, when you’re entering a conflict zone, your direct presence there becomes political,” researcher and adjunct professor, Sophie Kathyrn Fullerton told Al Jazeera.

A similar trend is increasingly evident in China. “I’m here because lots of people, right now, outside of China, want to know what Xinjiang is like,” says British vlogger, The China Traveller, at the start of a video, which focuses on him sampling a variety of local food while Uyghur women appeared to spontaneously dance behind him. Videos of this genre can be seen as part of what has been labelled the CCP’s project to “Disneyfy” Xinjiang. Uyghur culture has been co-opted by the state and amplified as a tourist attraction to change the narrative and drown out reports of genocide against the Uyghur community. In another video, The China Traveller praises the central government for rebuilding sections of the city, while failing to address the government’s other influence on the Xinjiang skyline: the mass demolition of religious institutions.

While Chinese culture is celebrated by The China Traveller and other vloggers in Xinjiang, French photographer Andrew Wack had a different experience when he returned to the region in 2019. Speaking to Wired a year after his trip, Wack commented on the stark absence of “men aged 20 to 60, many of whom had likely been rounded up and herded into indoctrination camps”. Throughout his visit, he was followed by plain-clothes police officers “and at checkpoints he was sometimes asked to show his photographs. On one occasion, he was asked to delete images”.

Many vloggers and journalists obscure any coordination or funding from Chinese bodies, or underplay how it may affect their coverage. Lee Barrett, a British vlogger, states in a video, “we go on some sponsored trips to places … our accommodation is paid for, our travel is paid for … nobody tells us what to say, nobody tells us what to film”. Due to the opaque nature of these relationships, it is impossible to interrogate the influence this type of support has on the vloggers’ reporting. However at times this veil is lifted. In a number of popular videos, minders sent by the Chinese state to monitor another vloggers’ trip can be clearly seen monitoring their behaviour.

When the BBC’s lead China reporter, John Sudworth, was invited into Xinjiang’s ‘re-education’ camps, he was presented with a highly choreographed and Disneyfied presentation of Xinjiang culture, which apparently even moved the Chinese officials accompanying the BBC crew to tears. However, Sudworth’s commitment to “peer beneath the official messaging and hold it up to as much scrutiny as we could” led him to scrutinise everything, including scraps of graffiti written in Uyghur and Chinese. This approach has had lasting consequences; he now reports on China from abroad, having had his visa revoked.

In modern day China, independent reporting from foreigners is one of the few avenues left in order to scrutinise power beyond the dominant state narrative. However, through the funding and coordination of junkets, training opportunities and other tactics, the Chinese state has followed in the footsteps of Assad’s Syria to try and control the message these foreigners send out into the world. This turns the principles of journalism against itself and manipulates the free expression environment in favour of the state.

Edgar Snow remains venerated in China. In 2021, the Foreign Ministry spokesperson Hua Chunying proclaimed on Twitter: “China hopes to see and welcome more Edgar Snows of this new era among foreign journalists”. John Sudworth provides a powerful counterweight, reminding us that we must “peer beneath the official messaging and hold it up to as much scrutiny as we could”.

- The authors approached The China Traveller and Lee Barrett for comment for this article. No response had been received by the time of going to press.

27 Oct 2020

[vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content_no_spaces” full_height=”yes” css=”.vc_custom_1603975708488{padding-top: 55px !important;padding-bottom: 155px !important;background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/the-diagnosis-credits-7.jpg?id=115407) !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;}” el_class=”text_white” el_id=”Introduction”][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Disease control: The diagnosis” font_container=”tag:h1|font_size:64|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” css=”.vc_custom_1603813903147{background-color: #000000 !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: contain !important;}”][vc_raw_html]JTNDZGl2JTIwc3R5bGUlM0QlMjJhbGlnbiUzQWNlbnRlciUzQm1hcmdpbiUzQWF1dG8lM0JiYWNrZ3JvdW5kLWNvbG9yJTNBcmdiYSUyODAlMkMwJTJDMCUyQzAuNSUyOSUzQiUyMiUzRSUzQ3AlMjBzdHlsZSUzRCUyMmZvbnQtc2l6ZSUzQSUyMDMycHglM0IlMjB0ZXh0LWFsaWduJTNBY2VudGVyJTNCd2lkdGglM0E2MCUyNSUzQm1hcmdpbiUzQWF1dG8lM0IlMjIlM0VIb3clMjBDb3ZpZCUyMHNwcmVhZCUyMGFuJTIwZXBpZGVtaWMlMjBvZiUyMGF0dGFja3MlMjBvbiUyMG1lZGlhJTIwZnJlZWRvbSUzQyUyRnAlM0UlM0MlMkZkaXYlM0U=[/vc_raw_html][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

Introduction

When the world first heard of a novel, flu-like virus emerging from the city of Wuhan in China, the team at Index immediately took an interest.

We could not have known how the world would be locked down in an unprecedented effort to control the spread of the virus – few could have predicted that. But what was clear even early on was that the news coming out of Wuhan was not the whole story. Once again, Chinese heavy-handed censorship was visible in underplaying the severity of the outbreak.

By the middle of February, we realised that this was no ordinary health crisis and that dramatic, global efforts would be necessary, including restrictions on individual freedoms – something which we do not accept lightly as an organisation.

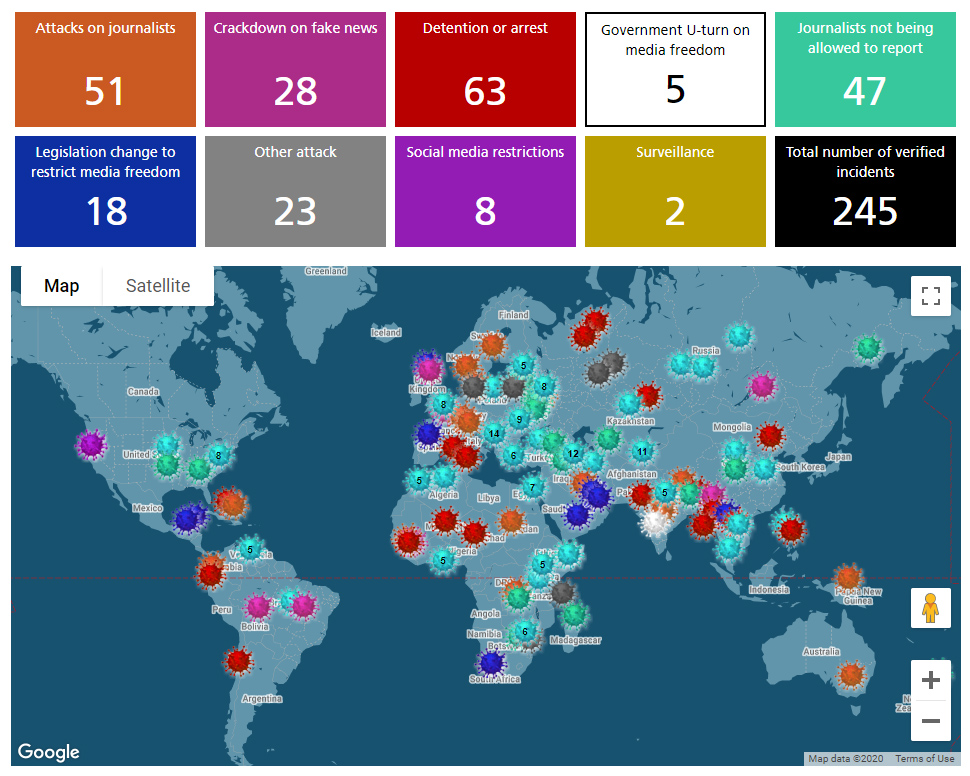

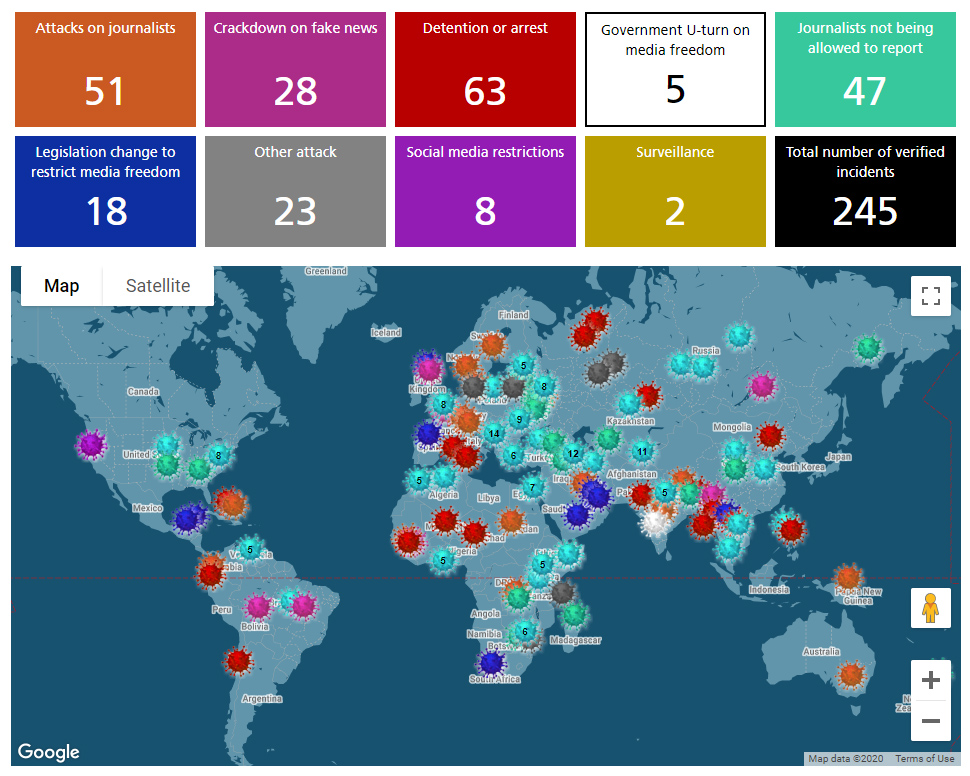

“That was a worrying signal,” said mapping project leader and Index associate editor Mark Frary. “Index’s experience in the nearly 50 years since it was founded is that moments of crisis are often used by governments to roll back on freedom of speech and the freedom of the media to report on what is happening. The public’s right to know can be severely reduced with little democratic process.”

Index has tracked this history, and has many examples published in our archive which covers the years 1972 to today. Even in February Index was already being alerted to attacks and violations against the media in the current coronavirus related crisis, as well as other alarming news pertaining to privacy and freedoms.

We knew from bitter experience that once these freedoms are eroded, they are hard to get back. We therefore saw raising awareness of any attacks during the Covid-19 pandemic as of paramount importance. We knew it would require a global response.

As a result, we began work on an interactive map to track attacks on media freedoms, the introduction of new legislation or changes to existing laws that threatened to stop journalists from doing their jobs and social media restrictions that threatened the free reporting of information.

Working with our partners at the Justice for Journalists Foundation, we asked our teams, our network of activists and our readers to report from around the world on cases where journalists were being silenced under the cover of Covid-19.

Speaking about the partnership, JFJ director Maria Ordzhonikidze said: “We were grateful to Index of Censorship for including the Justice for Journalists Foundation into the effort to monitor and analyse the global impact of Covid-19 on the freedom of speech. Autocratic regimes around the world used the pandemics as a pretext to further suppress any descent and independent reporting. Many countries swiftly introduced amendments to their criminal codes that enabled to arrest and put journalists behind the bars for alleged spreading of fake news and sowing panic. Silencing investigative reporting to hide the real statistics proved more efficient than fighting against the virus in those countries.”

Since then we have investigated hundreds of individual incidents, ranging from efforts by governments to restrict access to only approved journalists to physical attacks on reporters. We have investigated the disappearance of those reporting on social media and cases where journalists have been fined large sums for reporting what their governments have called ‘fake news’ but is, in reality, no such thing.

This report, eight months on from the launch of the Disease Control project, summarises what we and our partners have found in various regions of the world in the period from February to mid-September. More incidents have come to light since and we will continue to report on these attacks.

The purpose of this is not just to report on those incidents but to make sure that restrictive legislation is rolled back when the pandemic is over and that those who have reported on this crisis are not unfairly targeted or worse.

Map trends

[/vc_column_text][index_links category_id=”40456″][vc_empty_space height=”64px”][vc_single_image image=”115361″ img_size=”full” el_id=”China”][vc_column_text]

China

At the epicentre of the global pandemic that paralysed world economies was a country ranked the fourth worst in the world for media freedom.

At 177th place, China is by far the world’s worst in terms of major economies. The outbreak of coronavirus has done little to change the situation for its journalists and has only exacerbated the dire situation.

Reporters Sans Frontières described the situation: “President Xi Jinping has succeeded in imposing a social model in China based on control of news and information and online surveillance of its citizens.”

The group reports that more than 100 bloggers and journalists are currently detained.

Media restrictions can often be difficult to report on due to the severity of those media restrictions, but Index were still able to record a total of nine separate incidents in the country.

The Chinese government did its best to keep reports from the affected areas to a minimum. Businessman Fang Bin and journalist Chen Quishi gained thousands of views from videos they streamed in Wuhan. One video, posted by Fang, appeared to show a number of corpses piled into a van. Fang has been missing since February but the South China Morning Post revealed that Chen is alive and now living with his parents under surveillance.

Western journalists have been expelled due to how their papers have reported on the crisis. February saw three reporters from the Wall Street Journal forced to leave the country.

In March, China responded to the “unreasonable oppression” of its own journalists in the USA by expelling “at least” 13 journalists.

Social media in the country is heavily restricted. Pandemic related words were censored as soon as news of the virus came to light when a number of medical professionals including the late Dr Li Wenliang warned people of it.

The so-called “internet police” keep a watchful eye on China’s already heavily censored online world. Those pulled in for questioning for relatively innocuous, but critical, online posts are forced to sign a statement pledging loyalty to the ruling communist party.

A New York Times article described the policing: “Officers arrive with an unexpected rap at the door of online critics. They drag off offenders for hours of interrogation. They force their targets to sign loyalty pledges and recant remarks deemed politically unacceptable, even if those words were made in the relative privacy of a group chat.”

Resistance to such restrictions have been plentiful. Chinese magazine Ren Wu published an interview with a Wuhan doctor and whistle-blower who was critical of the situation. The online post was reportedly removed within hours, but the story remained circulating through other means. Some sites posted the interview backwards, while others used a form of code to bypass censors.

China’s clampdown on reporting has drawn criticism from those within and outside China for hindering attempts to control the virus. In February, RSF condemned censorship in China as harmful to fighting the virus.

The head of RSF’s East Asia desk Cédric Alviani said: “Censorship is clearly counter-productive in the fight against an epidemic and can only aggravate it or even help turn it into a pandemic.

“Only complete transparency will enable China to minimize the spread of false rumours and convince the population to follow the health and safety instructions recommended for curbing the epidemic.”

In response, a campaign of trying to defer blame and place it on the heads of Western powers quickly began. Chinese diplomat Lijian Zhao has been using Twitter to post ‘evidence’ that the virus originated in the USA.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”115359″ img_size=”full” el_id=”Asia_and_Australasia”][vc_column_text]

Asia and Australasia

Asia and Australasia (excluding China) recorded a total of 30 separate incidents of restrictions of journalists and media freedom. Due to their relative proximity to China, where the coronavirus originated, countries such as India, Cambodia and Myanmar were expected to introduce opportunistic and more restrictive laws to silence journalists and other forms of expression.

We reported on seven attacks on journalists in the region, five of which were in India.

In May, Index reported Indian journalists’ experiences of “unprecedented levels of censorship in the country”.

Anuradha Sharma’s article for Index spoke of the “stressed” relationship between journalists and state officials.

Sharma said: “Government interaction with the press is stressed. Prime Minister [Narendra] Modi, in keeping with his record, has not organised a single press conference on the issue. Harsha Vardhan, a health minister, has interacted infrequently with the press, while the daily press briefings are conducted by a senior bureaucrat in the health department, Lav Agarwal.”

You can read Sharma’s full report here.

Reports of journalists being assaulted have been frequent. March saw journalist Naveen Kumar beaten by police during routine checks on cars during a traffic jam.

After the incident, Kumar wrote: “I cannot describe it in words how outrageous, how scary and how painful it is. It seems like this shock has sat on my chest like a rock and will kill me.”

The political situation under the Modi regime is ever more constricting. Party allegiances can often lead to further violence such as in the case of Tripura-based journalist Parashar Biswas.

Biswas was attacked by a number of unidentified men in September. The men were said to be members the country’s ruling party Bharatiya Janata.

Recently, as Modi’s grip on media freedom tightens, the Indian Prime Minister froze the accounts of human rights group Amnesty International.

There were 11 arrests due to reporting on Covid-19.

Freedom of expression online was increasingly restricted and Cambodia’s alarming crackdown on ‘fake news’ was of considerable concern. According to Human Rights Watch, 30 people were arrested or detained for spreading false information from January to April, including journalists.

Journalist and director of TVFB news Sovann Rithy was charged with incitement to commit felony after publishing quotes from Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen on his Facebook page.

Hun Sen is known for his tight control of the media, so restrictions come as no surprise. Examples of other people warned included a 14-year-old girl, forced to make a public apology after posting on Facebook that three students at her school had contracted the virus.

Ros Sokhet, publisher of the Khmer Nation newspaper, was arrested in June for similarly critical online posts.

Legislative changes were fewer for the region, but this is perhaps more reflective of government’s handling a crisis that were already restrictive towards their citizens.

Malaysia, for example, has heard repeated calls for developments in its human rights and particularly for improvements to freedom of expression, according to Amnesty International. The Sedition Act and the Communications and Multimedia Act mean that only some criticism of the government is tolerated.

In July, Al Jazeera broadcasted a documentary made by Australian journalists about “undocumented” people living through the pandemic.

The documentary brought to light the treatment of migrant workers and the Malaysian authorities using the tight lockdown restrictions of the pandemic to arrest migrants.

Ranking 140th on the World Press Freedom Index, Thailand is already known for its lack of media freedom. An emergency decree brought in in March empowered authorities to instruct journalists to “correct” reports about the pandemic.

CPJ’s Southeast Asia representative said: “Thai authorities should not use the Covid-19 emergency situation as a pretext to censor or restrict journalists or media organisations.”

Oceania recorded three of the 30 total incidents. Most notably, New Zealand banned magazines and community newspapers as a “non-essential service”. The motion was questionable due to local communities’ reliance on locally sourced news.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”115369″ img_size=”full” el_id=”Former_Soviet_Union”][vc_column_text]

Former Soviet Union

Overall in the FSU countries, the Covid-19 pandemic became a convenient and widely used pretext for the authorities to further clamp down on critical reporting. The tactics of silencing independent media workers varied from country to country, but some common trends are visible.

In the group of dictatorships that deny the existence of Covid-19 in their states, such as Tajikistan and Belarus, media workers who wrote about the real state of affairs in hospitals, morgues, universities and shops were attacked and their publications suppressed. Turkmenistan falls into the same category of countries, however, JFJ received no reporting from the ground about attacks against independent media.

Autocracies that admit the existence of Covid-19, such as Russia, Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan, but also Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, have been widely prosecuting journalists for not following the variety of freshly introduced rules and regulations and spreading “fake news”. Fines, interrogations, administrative protocols, detentions, arrest and even lengthy prison sentences have been characteristic methods of suppressing independent reporting there.

In Ukraine, a country known for repeated physical hostility against journalists and a weak judiciary, in more than a half of registered incidents journalists were beaten up, detained and their equipment was seized or damaged by members of the public.

Media workers from Armenia, Georgia, Moldova and Kyrgyzstan, although silenced, threatened, summoned for questioning and deprived of access to information, were the least affected by the Covid-19 clampdown on media freedom out of the rest of the FSU countries.[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

Russia

In absolute figures, Russia is the record-setter in the number of Covid-19-related attacks against journalists, with 102 cases registered over the last six months.

Astonishingly, all three of the registered physical attacks were conducted in Russian orthodox churches in different locations during crowded Easter services. In two cases journalists were beaten and forcefully removed from the churches by priests and in the third instance by a celebrity actor turned religious fanatic, says our partner JFJ.

There were 15 cases of non-physical attacks with media workers verbally harassed, insulted, threatened and forced to delete or correct their publications under the pretext of them distributing “fake news”, “deliberately false information” or being involved in “extremist activity”. The perpetrators of such attacks were varied and included state TV propagandists, the police, local administrations, the State Duma committee for investigating the interference of foreign states, regional prosecutors, the FSB and the general prosecutor’s office.

The most widely used method of harassing the media workers in Russia is initiating administrative or even criminal proceedings against them. JFJ’s experts registered 50 incidents when administrative protocols and fines were issued to the media workers and outlets for distribution of fake news.

At the start of the pandemic, a new Article 207 of the Criminal Code on fake news about coronavirus was swiftly introduced and used to initiate at least 15 criminal cases against media workers. Under the pretext of investigating fake news about deaths, conditions in hospitals and the actual spread of the disease the police often illegally pressured journalists and bloggers to reveal their sources.

Some regions went further. For example, in Bryansk a criminal case was opened against Alexander Chernov on abuse of media freedom under Article 13.15, following his article questioning the effective measures taken by operational headquarters on coronavirus. And in Dagestan, Steven Derix of Handelsblat and his Russian film crew were detained while filming and charged with the violation of both the self-isolation regime and regime of counter-terrorism operation.

Using the pretext of pandemics, the police clamped down on the last legal method of protest available to the Russians – individual protests. Journalists who were either reporting on those or taking part in individual pickets themselves were routinely issued fines. JFJ registered a total of 18 cases where journalists received official warnings or fines for violating the rules of holding a protest, breaching the social distancing or self-isolation.[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text el_id=”Executive_summary”]

Most affected countries in the FSU

Kazakhstan saw 26 Covid-19-related attacks against media workers registered. This country swiftly introduced a state of emergency and issued numerous penalties, warnings and fines to media workers for violating it. The same pretext was used to deny journalists’ access to locations and information to cover the pandemic. For example, the annual parliamentary meeting to hear the government’s budget report was conducted behind closed doors – an unprecedented move. The meeting was not broadcast online either, with no official explanation provided.

At least five journalists and bloggers were summoned for lengthy and exhausting “talks” and interrogations following their critical publications on the subject for “dissemination of deliberately false information during the state of emergency”. Six media workers were detained and arrested for 10 to 60 days for violating the state of emergency. For example, civil activist Alnur Ilyashev was sentenced to three years of imprisonment and banned for five years on public activities for his Facebook post criticising the policies of the ruling party Nur Otan in regard to the pandemic.

Fourteen attacks were registered in Azerbaijan which gives this country the same risk coefficient as in Kazakhstan – 0.14 (attacks per 100’000). The authorities of these two countries treat their independent media in a very similar way: in Azerbaijan seven journalists were detained and arrested for up to a month for violating quarantine rules. For example, Ibrahim Vazirov was arrested after refusing to delete online reports about Covid-19, and given 25 days in prison for disobeying “a lawful request by the police”. Five more media workers were detained for violating the quarantine rules, fined and released.

Elchin Ismaillu, a newspaper reporter with Azadlyg, who had already been serving a prison sentence, was put into solitary confinement for five days after criticising the penal colony’s measures against the spread of Covid-19.

In Belarus, where authorities deny the existence of Covid-19 cases in the country, attacks against journalists who covered the pandemics looked somewhat schizophrenic.

On one hand, several media outlets received official letters from the Ministry of Information requesting that published stories detailing the spread of the pandemic in Belarus be deleted. The mirror site of the forbidden news media website Charter 97 that reported on deaths from Covid-19 in the country was blocked entirely. Some bloggers, like Olga Zhuravskaya, who brought her son to test for the disease and recorded the process in her blog, were fined for hooliganism. Journalists Larissa Shirokova and Andrei Tolchin, who reported about the first death and dozens of hospitalisations, were fined for producing media content without a licence and its illegal dissemination. Media-Polesie agency was fined for “sharing prohibited content” that was “damaging to the national interests of the Republic of Belarus”.

Even journalists from the Russian official broadcaster Channel 1 covering the pandemic in Belarus had their accreditations cancelled for “spreading information that did not correspond to reality”.

At the same time, under the pretext of “the epidemiological situation in the country”, several journalists from independent outlets, including Radio Liberty, were refused access to official Parliamentary meetings, and the accreditation of BelaPan was withdrawn.

Vasili Matskevich, journalist and a member of the Belarusian Association of Journalists, tragically died in April aged just 46 from what was officially acknowledged as pneumonia.

Ukraine saw 35 incidents of Covid-19-related attacks against media workers. This country upheld its position as having the most dangerous environment for journalists with 23 recorded incidents of physical violence. Journalists were beaten up and their equipment and recordings destroyed while they were gathering evidence on how various businesses, churches and other premises were complying with the quarantine rules. One example is the violent attack on the camera crew of Espresso.TV near a cafe. After the correspondent Ilia Eulash went on the air, an unidentified man ran up to the camera crew, grabbed the camera and threw it into the river. Another reporter, Dina Zelenskaya, started to film the unfolding attack on her mobile phone. The man ran up to her, knocked Zelenskaya to the ground and grabbed her hair. Then he ripped her phone out and threw it into the river.

Bogdan Kutepov of Hromadske.ua was beaten up by the police in Kyiv’s Mariinsky Park while he was broadcasting a rally by entrepreneurs demanding the government terminate the lockdown. That was the only registered physical attack by the authorities.

There were nine incidents of police preventing journalists access to court hearings, city councils and other official buildings and events under the pretext of quarantine and social distancing measures. In two cases, security guards and orthodox priests blocked camera crews trying to film quarantine measures relating to church buildings.[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text el_id=”Defamation_law”]

Least affected countries in the FSU

Moldova remained largely unaffected by repressive Covid-19 restrictions, with just one case of harassment and insult registered against Diana Gatcan from Ziarul de Garda newspaper.

In Georgia, out of seven recorded incidents, two were physical attacks against journalists aimed at preventing them from reporting on the pandemic. Blogger Giorgi Chartoliani was attacked at a protest against lockdown measures in Mestia, Svanetia, and journalist Gocha Barnovy attacked during his interview with Rustavi-2 TV about the lack of protective measures in Georgian orthodox churches during Easter services.

Two freelance journalists – Khatuna Samnidze and Nino Chelidze – were summoned for interrogation by the Georgian State Security Services for their Facebook posts on mortality rates and statistics of Covid-19 cases in Georgia.

Armenia, with its population of 3 million, seems to have the highest risk coefficient per 100’000 – 0.67. However, all 20 recorded incidents related to police letters to media outlets requesting removal of a Covid-19 related story that contained criticism of government policies. In many of these cases the media refused to abide without any consequences.

In Tajikistan, the authoritarian state where monitoring of attacks against media is severely constrained, the authorities deny the existence of Covid-19 cases. Independent journalists and media who reported objective facts about the medical and economic impact of the pandemics were silenced by police “for sowing panic”. The Radio Liberty-Radio Ozodi website was blocked, and media workers who had expressed critical opinions received death threats and insults via phone and social media. Our experts registered five incidents.

In Uzbekistan, with just 11 recorded incidents, the authorities widely used new Covid-related restrictions to suppress independent reporting. Several media workers were fined for not wearing a mask, five bloggers were sentenced to between seven and 15 days in prison for “violating quarantine rules”, and there were two failed and one successful attempt to forcefully quarantine independent journalists without any legal basis. All of the attacked media workers are known for their objective reporting on the economic toll of the pandemic and criticising government policies in relation to Covid-19.

In Kyrgyzstan the government swiftly introduced a state of emergency and only provided the state-owned broadcaster KTK with access to information. It refused to accredit other journalists, nor did it share official information with any independent reporters. This was done under the pretext of health considerations, in direct contradiction of the country’s legislation.

At the same time, the tragic death of Kyrgyz journalist and human rights activist Azimzhon Askarov, who was serving his 11th year in prison, is widely considered to result from infection with Covid-19 and a lack of medical help in prison.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”115353″ img_size=”full” el_id=”North_America”][vc_column_text]

North America

In North America, Index verified a total of 15 incidents, most common of which were attacks on journalists. All verified instances were in the United States.

Media freedom has been under attack in the US under President Donald Trump and trust in journalists has fallen.

The US press freedom tracker has logged 201 journalists attacked, 58 equipment damages, 63 journalists arrested and 10 occasions where equipment was searched or seized in this year alone.

The tracker is run by Freedom of the Press Foundation and the Committee to Protect Journalists in collaboration with other media freedom groups including Index.

A catalyst for attacks on journalists in the country has been the Black Lives Matter protests after the killing of George Floyd. Since the protests began, over 825 reported aggressions towards journalists during protests have been registered.

With specific focus on the Covid-19 pandemic, Trump has regularly attacked journalists as a cover for his own poor handling of the crisis and eight of the 15 incidents were such attacks.

A typical incident was on 19 May when CBS’ Paula Reid asked Donald Trump why there seemed to be no plan to get 36 million unemployed Americans back in to work. The president replied: “Oh, I think we have announced a plan. We are opening up our country — just a rude person, you are. We are opening up our country, and we’re opening it up very fast.

“The plan is each state is opening and it is opening up very effectively, and when you see the numbers I think even you will be impressed, which is pretty hard to impress you.”

In June Index joined with 71 other press freedom organisations to write to the president to condemn recent attacks on the media and express concerns over an apparent lack of commitment to hold up the values of the First Amendment.

The letter stated: “Press freedom in the United States is critical to people around the world. Thousands of foreign correspondents are based in Washington D.C. and throughout the U.S., where they are tasked with telling the story of America to their publics back home. The ability of journalists to work freely in the U.S. creates a more enlightened global citizenry.”

“Instead of condemning journalists and the media, we urge you to commend and celebrate them as the embodiment of the First Amendment, which is the envy of so many countries around the world.”

Canada has avoided clamping down on the media during the crisis.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”115355″ img_size=”full” el_id=”Central_and_South_America”][vc_column_text]

Central and South America

Our map for Central and South America recorded a total of 17 incidents during the Covid-19 pandemic. The most common incident was detention or arrest.

Similar to incidents across the border in the USA, journalists were targeted during protests. In Chile during 1 May demonstrations, 15 journalists were rounded up and arrested as part of a police plan to break up demonstrations.

Police claimed the crowd was broken up only due to restrictions of large gatherings of over 50 people due to the pandemic. Spanish newspaper La Vanguardia claimed such scenes had “not been common since the Pinochet dictatorship”.

There were also reports of excessive force by police to break up a peaceful protest in Ecuador. A number of protesters were beaten and journalists were also attacked, according to HRW.

Changes to legislation in the region have also been common. The pandemic has provided governments in the region with the perfect opportunity to introduce controversial and restrictive legislation, such as the extraordinary measures applied in Bolivia.

The decree, announced in April, mean journalists in the country could face up to 10 years in prison should they prove to be “individuals who misinform or cause uncertainty to the population”.

The law was removed a month later.

Freedom of Information requests – also known as access to information laws – are vital to upholding democracies and holding authorities accountable at both the state and local level. In Brazil, President Jair Bolsonaro issued a measure that ensured information requests no longer had to adhere to a deadline. The move essentially ensured that, in attempts to access public information, the government was no longer accountable.

The incident furthered concern over the Bolsonaro government and its approach to media freedom.

Wagner Rosário, current minister of transparency, supervision and control, said that authorities and relevant ministerial departments would be unable to respond to questions due to being “completely involved in the fight against the coronavirus”.

Despite this, Bolsonaro has been dismissive of the virus, claiming it as a ‘little flu’ – claims which have heightened suspicion of the media.

Similar to the fake news claims of President Donald Trump, Bolsonaro blamed media “hysteria” and a “shameless campaign against the head of state”.

“The people will soon see that they were tricked by [a] large part of the media when it comes to coronavirus,” he said.

Bolsonaro has a track record of attacking the media. By the end of August, Brazil’s National Journalists’ Federation had recorded 116 incidents where the president attacked journalists.

In 2020 El Salvador implemented legislative changes similar to those in Brazil, wherein the Salvadoran government sought to restrict access to public information.

Current president of El Salvador Nayib Bukele has faced criticism of his presidency; some claiming him to be an autocrat after storming the legislative assembly with troops in February to demand further loans.

In neighbouring Honduras, President Juan Orlando Hernández brought in a seven-day state of emergency, revoking a number of articles of the Honduran constitution. Article 72 of the enshrined text provides protections to journalists as well as the right to free expression without censorship. This article was also revoked when the declaration took place in March.

Much of the region is continuing to face concerning developments (not just during the pandemic) regarding limitations to media freedom. The pandemic has provided ample opportunity to different governments, already facing criticism for their handling of the coronavirus crisis, as well as other public issues of importance. Often the work is undermined by states insistence journalists do not help uphold democracy.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”115373″ img_size=”full” el_id=”North_Africa”][vc_column_text]

North Africa

North African governments have taken advantage of the pandemic to pass laws inhibiting freedom of expression; arrest local bloggers, journalists, and protesters; and silence foreign media.

We identified three trends in the region: the use of emergency powers to pass “fake news” bans; the crackdown on local bloggers, journalists and protesters; and the targeting of foreign press.

In April, the government in Algeria criminalised the dissemination of fake news, its stated aim being to limit the spread of false and detrimental information regarding coronavirus. Following the “false news” ban, L’Avant-Garde, Le Matin D’Algérie and DZvid all reported that their news sites had been made inaccessible from Algeria. The three outlets had all recently reported on anti-government protests and Covid-19’s development in the area.

According to Sayadi, while Egypt is the “tsar” of website blocking, Algeria has only ever shut down the internet to silence protesters and journalists. Sayadi expressed concern over this development in Algeria’s media suppression tactics: “As a civil society activist who has been working on Algeria for four years now, it’s… very strange to see [what] the Algerian government is doing.”

Also in April, Egypt’s general prosecution declared in April that disseminating false information about Covid-19 could lead to jail sentences of up to five years and fines of up to EGP 20,000.

A “fake news” law was proposed in Tunisia in March and then withdrawn in the face of public outcry. Sayadi, based in Tunisia, commented on this legislative attempt’s implications: “Tunisia… is known to be the example in the MENA countries of democracy and freedom of speech… We don’t have any websites blocked and we don’t have anything censored. But at the same time… the government is trying to get on [top] of everything that was a little bit freed by the revolution.”

Mohamed Ali Bouchiba, Secretary General of the Tunisian lawyers association Bloggers Without Chains, commented on the arrest of his client, Anis Mabrouki: “During the Covid-19 period, [Mabrouki] wrote a post talking especially about the abuses of local authorities regarding the distribution of resources like flour and oil… All he did is that he tried to show people what was happening, to peacefully criticise things that were not acceptable. Things that touch the humanity of the people who we leave outside in the sun; all this for nothing but a little food during the very delicate period of Covid-19 self-confinement.”

Blogger Emna Charqui was also arrested in Tunisia after making a satirical post about hand-washing’s importance during Covid-19. For jokingly using Koran-like language, she was sentenced to six months in prison for “inciting hatred of religion”.

Algerian journalist Merzoug Touati, having recently posted an interview with a medical professional about the state of the pandemic in Algeria, was arrested while reporting on anti-government protests. Among other things, he was charged with endangering lives by disregarding lockdown restrictions. Moroccan journalist Abdel Fattah Bouchikhi was arrested and sentenced for defamation after making an online post criticising the corrupt and unequal distribution of transport permits that authorise movement in Morocco during lockdown.

Protesters Ahdaf Soueif, Laila Soueif, Mona Seif and Rabab El-Mahdi were arrested for condemning the coronavirus exposure risks that Egyptian prisons present to detainees. They additionally called for the release of bloggers and activists like Alaa Abd El Fattah.

After quoting Canadian case projections for Egypt instead of Egypt’s official figures, Guardian correspondent Ruth Michaelson’s press credentials were revoked by the State Information Service.

The ministry of culture, youth, and sports’ communications in Morocco called the foreign press’s use of independently gathered Covid-19 data “professional misconduct” and stressed the need for journalists to meet the field’s code of ethics going forward.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”115357″ img_size=”full” el_id=”Sub-Saharan_Africa”][vc_column_text]

Sub-Saharan Africa

Thirty-four incidents were recorded on our media freedom map in sub-Saharan Africa during the pandemic and journalists being arrested or detained was common, with 10 incidents reported.

An alarming trend appeared in Zimbabwe. Two journalists were arrested in May for “breaking lockdown rules” when attempting to interview members of the government’s opposition who had sustained injuries at the hands of those suspected to be security agents.

At the time, Paidamoyo Saurombe, a Zimbabwean human rights lawyer, told VOA news: “It is disturbing. Why would you arrest someone who is going to work? You never know. It becomes scary that if you are arrested while going to work, what else will happen?”

The two journalists, Frank Chikowore and Samuel Takawira, were eventually discharged and acquitted, but actions towards journalism in the country remain worrying, such as in the case of Hopewell Chin’ono. Chin’ono brought to light a case of procurement fraud within the country’s health ministry. He was subsequently arrested for inciting violence and has since been granted bail.

Chin’ono, 49, told the Daily Maverick: “My arrest was meant to put the fear of God into other journalists – a warning that this is what happens if you tarnish the image of the president. I am worried about journalists: there is a history of abductions, there is fear.”

Under the current president Muhammadu Buhari, Nigeria has slipped to 115th in the World Press Freedom Index. Buhari’s government also implemented legislative changes in April, decreeing that all journalists should carry identity cards.

In April, there were 12 arbitrary arrests at the Adamawa State Secretariat of the Nigeria Union of Journalists.

Further arrests were made in Niger, Liberia, Ethiopia, Kenya and Somalia.

Africa, compared to the rest of the world, has been less severely affected by the pandemic; the current death toll for the whole of the continent is now nearing 36,000. However, this has not stopped the implementation of Covid-19 specific legislation aimed at reporters.

Ghana introduced the Imposition of Restrictions Act, enforcing strict measures including the government’s ability to intercept communication. Breaking this act could see punishments of heavy fines and up to 10 years in prison. The law was introduced despite Ghana already having legislation in place to enforce stricter measures in the country during times of crisis.

The crackdown in South Africa on the spreading of misinformation also sets a troubling precedent. The legislation, which criminalises malicious disinformation regarding Covid-19 related information, caused concerns that the censorship law could lead to a limited amount of access for the public to necessary information.

South Africa’s government has also clamped down upon the spreading of information by medical experts. In an effort to “reduce the noise”, new rules stopped information getting into the public sphere through non-government sources, causing frustration among journalists unable to report using expert opinion.

Additional cases of reporters being unable to report occurred in Somalia, Tanzania, Zambia and Madagascar, where Reporters Sans Frontières condemned an act of sabotage to a television channel.

The President of Madagascar, Andry Rajoelinam, was the subject of criticism by an opponent over his government’s management of the crisis. Broadcast channel Real TV planned to retransmit the heavily critical interview but one of its transmitters was sabotaged.

Other stations had received formal warnings regarding their own coverage, deemed unhelpful to the government.

Elsewhere, Liberia fell foul of condemnation from a US official in May. Assistant secretary of state for African affairs Tibor Nagy accused the West African country of media suppression. The previous month saw threats from Syrenius Cephus, Liberia’s solicitor general, to take away equipment and close down media organisations for spreading misinformation.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”115364″ img_size=”full” el_id=”Northern_Europe”][vc_column_text]

Northern Europe

Media freedom is not usually an issue in northern Europe. The top four countries in RSF’s World Press Freedom Index are all in the region and the lowest ranking country in the continent’s northern half is the United Kingdom.

This open environment has not, however, stopped the media and journalism coming under attack during the Covid-19 pandemic, underlining how we are living in unprecedented times.

In the UK, the focus from the government was on tightly controlling the news agenda. Early in the pandemic some doctors and medical staff working at the frontline were told they were not allowed to speak with the media about the shortage of personal protection equipment in particular.

One local news reporter faced criticism from government ministers after an exclusive about housing the homeless during the crisis. One seasoned lobby journalist was told they could not ask tough questions at the government’s high profile and highly managed daily press briefings.

Scotland also appeared on our map for attempts to restrict freedom of information requests during the crisis, leading Neil Mackay, a writer at large for The Herald, to say: “In what should be a badge of shame for the SNP, the Index on Censorship named Scotland alongside Brazil in a report on the erosion of FoI globally during coronavirus.”

This was not an isolated incident in Europe either. In Belgium, Alexandre Penasse, the editor-in-chief of Kairos, was banned from press conferences by the Belgian federal government after the prime minister refused to answer his question and accused him of provocation.

Control was also the issue in France where a local journalism union forced the government to remove a website that attempted to debunk misinformation around Covid-19. The union said the government should not set itself up as an arbiter of the truth around the virus.

During the pandemic, cartoonists in northern Europe have become a focus for criticism for their work.

Satirical cartoonists are often the target for criticism from the rich and powerful but these attacks increased during Covid-19. Cartoonists Rights Network International said there had been more than twice the number of attacks against cartoonists between the months of March and May this year than there normally are.

CRNI executive director Terry Anderson said: “Because so many things in their common life are gone, people are consuming information in a much higher quantity, so when a news story breaks, everyone is paying attention. If there’s a cartoon that pisses people off, it’s going to piss off far more people far more quickly.”

Cartoonists in Belgium, Denmark and Sweden came under fire for their work relating to Covid-19, including Stephen Degryse, better known as Lectrr. His cartoon of a Chinese flag with biohazard symbols instead of stars drew sharp criticism.

“I started to receive a lot of hate mail on my social media, most of it in Chinese, and a lot by fake accounts and manufactured texts. After a while I also received a death threat by one of the accounts,” he said.

Sadly, journalists have also become a target for people angry about lockdown restrictions. An incident took place in the Hague in the Netherlands where photographer Pierre Crom was attacked by market vendors. In Germany, a camera crew from TV broadcaster ZDF were attacked while filming a satirical “hygiene demonstration” for the channel’s Heute Show.

Inevitably, the Covid pandemic has required restrictions on some freedoms, such as the freedom of movement between the countries of Europe. However, it is clear that even beyond the restrictions designed to stop the spread of Covid, many European countries have not been immune from introducing other measures that have the consequence of stopping reporters from doing their jobs.

[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”115367″ img_size=”full” el_id=”Eastern_Europe”][vc_column_text]

Eastern Europe

Some parts of Eastern Europe have a growing problem with media freedom.

Turkey has been clamping down throughout President Recep Tayyib Erdogan’s rule and this was accelerated after the failed coup in 2016.

Things have been getting worse during Covid-19 in the country. Several broadcasters and journalists who have tried to share the truth about Covid-19 have been attacked. Television channel KRT was fined for questioning the state response to the pandemic, while Tugay Can, a journalist with the Izmir Gazete, was questioned by the police after writing about new cases in the city. In Kocaeli, two executives from the Ses newspaper were detained after it published a story on two local coronavirus deaths; it has since promised to publish only official stories.

Meanwhile, the country has been debating the introduction of rules that would require social media users to register to use these platforms.

Over in Hungary, Viktor Orban has been challenging Erdogan for the title of the most repressive leader using Covid-19 as an excuse.

Orban quickly moved to take what some called dictatorial control of the country during the early stages of the pandemic, allowing him to rule by decree. The country’s civil liberties union criticised the centralisation and restriction of news around the pandemic and said the government restrictions had been particularly detrimental to independent media.

Meanwhile, Hungarian cartoonist Gábor Pápai was threatened with a lawsuit by the Christian Democrat party after producing a caricature of the country’s chief medical officer at its public health department. The cartoon shows Cecilia Müller facing Jesus crucified on his cross and pronouncing: “His underlying condition caused dependence”.

Bosnia’s Republika Srpska banned publishing “false news and allegations that cause panic and severely disrupt public order and peace or prevent the implementation of measures by institutions exercising public authority”, for example.

In Serbia, Nova.rs online journalist Ana Lalic was arrested after publishing a story on Vojvodina Clinical Center. She was later released but the complaint was not withdrawn and her equipment was seized.

In April, a group of TV reporters in Bosnia and Herzegovina were detained by police while reporting on citizens attending a Covid-19 isolation clinic in the country. Their phones were taken and their footage deleted.

The FoI restrictions introduced elsewhere in the world, such as in Scotland and Brazil, were also introduced in eastern Europe, notably in Romania where response times were doubled.

In Poland, LPP issued a lawsuit claiming damages of 3 million Polish złoty (nearly €1 million) against Newsweek Poland and journalists Wojciech Cieśla and Julia Dauksza following the publication of an article, reporting that the Polish clothing company had bought a supply of several hundred thousand protective masks and sent them to their workers in China in order to maintain production continuity.

Meanwhile, a Polish public radio station was accused of censoring a chart-topping song because it is widely believed to criticise Poland’s ruling party leader Jaroslaw Kaczyński, who had visited a cemetery during the crisis despite a ban on this activity.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”115372″ img_size=”full” el_id=”Southern_Europe”][vc_column_text]

Southern Europe

A common theme in Southern Europe during the Covid-19 pandemic has been attacks on journalists by the public.

A journalist and photographer from Il Tirreno newspaper in Italy were attacked on 23 March after going to interview a newsagent for an article on the coronavirus measures.

According to Il Tirreno, the newsagent “insulted them in front of customers, then came out of the kiosk holding the iron rod used to raise and lower the shutter, threatening them to use it against them”.

In another incident, a photographer in Turin was attacked and his camera memory card stolen after trying to report on markets that were operating illegally during the crisis.

In Kosovo, journalists Nebih Maxhuni and Diamant Bajra and cameraman Arsim Rexhepi were attacked while reporting on the pandemic. The head of the OSCE said it was important “that people remain calm in these difficult times and that journalists are allowed to work without fear of violence”.

Elsewhere state control was the issue.

In Spain, the desire by the government to keep control of questioning during official press conferences boiled over, as it has done in other parts of Europe. Over 400 Spanish journalists signed an open letter asking the government to revise the policy which means questions are sent to the press secretary, who can chose to ask them, or not, impacting on journalists’ ability to hold power to account.

Slovenia’s government communication office (Ukom) has announced that regular statements will now be made directly through Television Slovenia and the presence of media representatives is no longer possible. The Journalists Association of Slovenia says the measure is “disproportionate and restrictive”.

Slovenian investigative journalist Blaž Zgaga has been subject to death threats and a smear campaign since submitting a request for information to the government about its management of the coronavirus crisis.[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

Acknowledgments

Photo credits: Etienne Godiard/Unsplash (main image), Andreas Schneemayer (Beijing), Rhiannon (India), Thierry Ehrmann (Putin graffiti, Russia/CC BY 2.0), Luis Valiente (Niagara falls), Gil Prata (Brazilian police), Monica Volpin (Marrakesh), Jozua Douglas (Ghana), Dimitris Vetsikas (Copenhagen), Alexey Mikhaylov (Hungary), c1n3ma (Madrid)[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”115408″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.jfj.fund”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]This report has been supported by the London-based Justice for Journalists Foundation. The foundation was created in August 2018 by Mikhail Khodorkovsky, founder of the Open Russia pro-democracy movement, an Amnesty International-recognised prisoner of conscience, and Putin’s most prominent critic, together with his former business partner, philanthropist and member of the Free Russia Forum’s standing committee Leonid Nevzlin.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][/vc_column][/vc_row]