22 Aug 2013 | Egypt, News and features, Politics and Society

Egypt faced a new phase of uncertainty after the bloodiest day since its Arab Spring began, with nearly 300 people reported killed and thousands injured as police smashed two protest camps of supporters of the deposed Islamist president. (Photo: Nameer Galal / Demotix)

Nearly 1,000 people have been killed in Egypt in a week of deadly violence that began with a brutal security crackdown on Islamist protesters staging two sit ins in Cairo to demand the reinstatement of the country’s first democratically-elected president Mohamed Morsi . Six weeks earlier, Morsi had been removed from office by the military after millions of Egyptians took to the streets calling on him to step down and hold early presidential elections. Ever since the military takeover, hundreds of Muslim Brotherhood supporters have been killed or arrested as the Egyptian military and police pursue what they describe as an “anti- terrorism drive”.

The majority of Egyptians have expressed their support for the military and police , cheering them on in their sweeping campaign “to rid the country of the scourge of terrorism” and at times, launching verbal and physical attacks on the pro-Morsi protesters. Islamist supporters of the deposed president have meanwhile continued to stage rallies across the country, condemning the violence.

Egyptian media has also chosen to side with the country’s powerful security apparatus and has consistently glorified the military while demonizing the toppled president’s supporters. The text “Together against terrorism” appears on the bottom corner of the screen on most state and independent TV channels. In this bitterly polarized and often dangerous environment, it is the journalists covering the unrest that are caught in the middle, facing detention, intimidation, assault and sometimes, even death.

Tamer Abdel Raouf, an Egyptian journalist who worked for the state sponsored Al Ahram newspaper last week became the fifth journalist to die in the unrest when he was shot by soldiers at a military checkpoint “for failing to observe the nighttime curfew.” Abdel Raouf had been driving in Al Beheira when he was ordered by soldiers to turn back. While the soldiers claim he did not heed the warnings , another journalist accompanying him in the car said that Abdel Raouf had in fact been making a U turn when the soldiers fired their guns , instantly killing him. Prior to his death, he had persistently criticized the manner in which “the legitimate” president was ousted.

Other Egyptian journalists critical of the coup have meanwhile, faced intimidation and threats. The handful of Egyptian journalists who have remained unbiased, refusing to take sides in the conflict, have faced the wrath of an increasingly intolerant public that has labelled them “traitors” and “foreign agents.” A reporter working for an international news network who chooses to remain anonymous, told Index she had received threats via her Facebook account urging her to “remain quiet or be silenced forever.” The messages were sent by people claiming affiliations with Egypt’s security apparatus including the Egyptian intelligence , she said. “You will be made to pay for your stance,” read one message while another warned she would be physically attacked for being “a traitor and an enemy of the state.”

However, it is Western journalists that are bearing the brunt of the mounting anger in the deeply divided nation. The government has accused them of “being biased” in favor of the Islamists and of failing to “understand the full picture”.

“Some Western media coverage ignores shedding light on violent and terror acts that are perpetrated by the Muslim Brotherhood in the form of intimidation operations and terrorizing citizens,” a statement released by the State Information Service (SIS), the official foreign press coordination center said. SIS officials have also affirmed that no ‘coverage authorizations’ would be granted to foreign journalists unless they receive prior approval from Egyptian intelligence –a marked shift meant to restrict coverage to “journalists who have not ruffled the feathers of the authorities,” an SIS official who does not wish to be named, disclosed.

Meanwhile, in recent meetings with representatives of foreign media outlets, Foreign Minister Nabil Fahmy and presidential spokesman Ahmed Mosslemany have accused the Western press of conveying a “distorted image” of the events in Egypt. They urged the journalists to rein in their criticism of the government and to try and “see the full picture”. “Why is the Western media not covering the ‘terror’ acts committed by the Muslim Brotherhood including attacks on churches and police stations instead of devoting their coverage to assaults by security forces on pro-Morsi protesters?” they quizzed.

Western journalists deny that their coverage has been one-sided insisting that they had travelled to southern provinces where sectarian violence is rampant. Several foreign reporters have meanwhile, been subjected to harassment, assaults and detentions by security forces and popular vigilante groups while covering the recent clashes between pro-Morsi protesters and security forces.

Last Saturday marked a day of increased violence against Western journalists with at least six foreign correspondents reporting harassment and assaults while attempting to cover the siege on a mosque in downtown Cairo where pro_Morsi protesters had sought refuge after clashes with security forces. Two foreign journalists –the Wall Street Journal’s Matt Bradley and Alastair Beach, a correspondent with the Independent –sustained minor injuries when they were attacked by assailants outside the mosque but army soldier momentarily intervened, shielding them from the angry mob and dragging them to safety. Patrick Kingsley, a correspondent for the Guardian, was meanwhile, briefly detained and questioned by several suspicious vigilante groups and by police as he attempted to cover the mosque siege on Saturday. He later complained on Twitter that his equipment –including a laptop and cell phone– was seized in the process.

Abdulla Al Shami, a correspondent with Al Jazeera who was detained on Wednesday 14 August while covering the security crackdown on the Rab’aa pro-Morsi sit in, remains in police custody at an undisclosed location, according to the New York-based Committee for the Protection of Journalists. Mohamed Badr, a photographer working for the news channel has meanwhile been in detention since July 15 on the charge of possessing weapons—an accusation denied by Al Jazeera. Moreover, the offices of Al Jazeera Arabic were ransacked and shut down by police last week . Egyptian authorities are considering suspending Al Jazeera Mubasher’s license, accusing the network of “a clear pro-Morsi bias ” according to state owned Al Ahram newspaper. Many Egyptians are also accusing Al Jazeera of “inciting violence “ and of “threatening national security.”

The stepped up attacks on foreign journalists come at a time when the new interim government faces a chorus of international condemnation over its handling of the current political crisis. Clearly determined to crush the Muslim Brotherhood , the authorities remain defiant rejecting all attempts at reconciliation with the Islamists as “meddling in the country’s internal affairs.” Anyone remotely suggesting that the military should reconcile with the Muslim Brotherhood, the long detested arch-enemy, is accused of being a “traitor” and a “threat to the nation’s security”. Hence, the legal complaints recently filed against Vice President for Foreign Affairs Mohamed El Baradei who resigned his post earlier this month after security forces forcibly broke up the pro_Morsi sit ins.

In the divided country, Egyptians have adopted an uncompromising attitude of “you are either with us or against us”. The government has meanwhile encouraged such attitude by praising and rewarding “the patriots”. In such an atmosphere, there is no room for objectivity and any neutral media that reports without bias is accused of being pro-Islamist and perceived as “the enemy”.

Reverting back to Mubarak-era tactics, the government is determined to silence the voices of dissent.

14 Aug 2013 | Egypt, News and features, Politics and Society, Religion and Culture

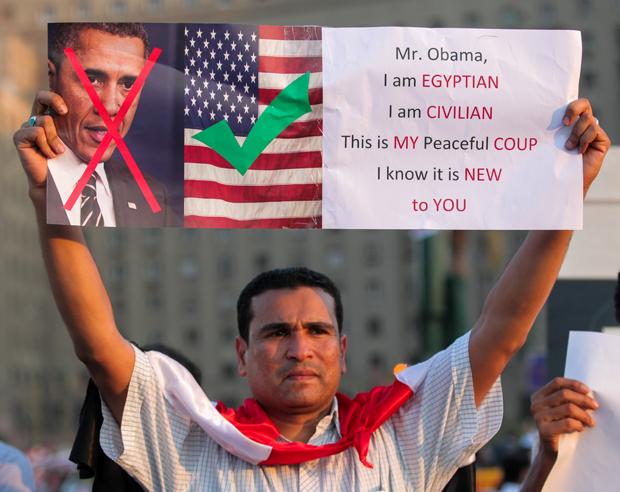

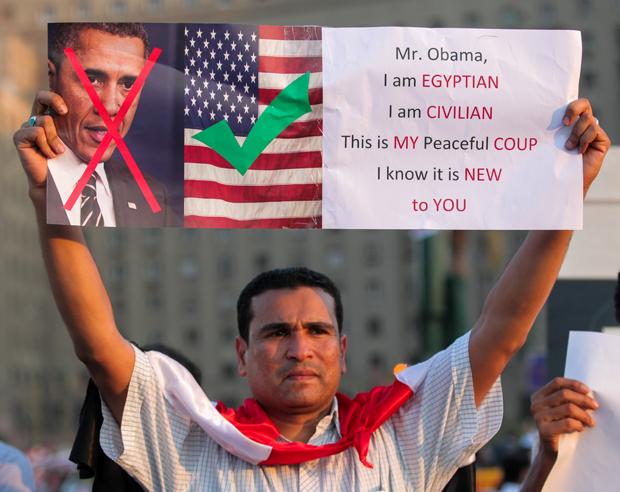

An Egyptian protestor holds a sign showing the anger of some Egyptian people towards the American government. (Photo: Amr Abdel-Hadi / Demotix)

Index on Censorship condemns today’s attacks on protest camps in Cairo and other cities and calls on Egyptian authorities to respect the right to peaceful protest. Live coverage Al Jazeera | BBC | The Guardian

Xenophobia in general and anti-US sentiment, in particular, have peaked in Egypt since the June 30 rebellion that toppled Islamist President Mohamed Morsi and the Egyptian media has, in recent weeks, been fuelling both.

Some Egyptian newspapers and television news has been awash with harsh criticism of the US administration perceived by the pro-military, anti-Morsi camp as aligning itself with the Muslim Brotherhood. The media has also contributed to the increased suspicion and distrust of foreigners, intermittently accusing them of “meddling in Egypt’s internal affairs” and “sowing seeds of dissent to cause further unrest”.

A front page headline in bold red print in the semi-official Al Akhbar newspaper on Friday 8 Aug proclaimed that “Egypt rejects the advice of the American Satan.” The paper quoted “judicial sources” as saying there was evidence that the US embassy had committed “crimes” during the January 2011 uprising, including positioning snipers on rooftops to kill opposition protesters in Tahrir Square.

The stream of anti-US rhetoric in both the Egyptian state and privately-owned media has come in parallel with criticism of US policies toward Egypt by the country’s de facto ruler, Defense Minister Abdel Fattah el Sissi, who in a rare interview last week, told the Washington Post that the “US administration had turned its back on Egyptians, ignoring the will of the people of Egypt.” He added that “Egyptians would not forget this.”

Demonizing the US is not a new trend in Egypt. In fact, anti-Americanism is common in the country where the government has often diverted attention away from its own failures by pointing the finger of blame at the United States. The public has meanwhile, been eager to play along, frustrated by what is often perceived as “a clear US bias towards Israel”.

In Cairo’s Tahrir Square, anti-American banners reflect the increased hostility toward the US harboured by opponents of the ousted president and pro-Morsi protesters alike, with each camp accusing the US of supporting their rivals. One banner depicts a bearded Obama and suggests that “the US President supports terrorism” while another depicts US ambassador to Egypt Anne Patterson with a blood red X mark across her face.

The expected nomination of US Ambassador Robert Ford — a former ambassador to Syria who publicly backed the Syrian opposition that is waging war to bring down the regime of Bashar El Assad — to replace Patterson, has infuriated Egyptian revolutionaries, many of whom have vented their anger on social media networks Facebook and Twitter. In a fierce online campaign against him by the activists, Ford has been criticized as the “new sponsor of terror” with critics warning he may be “targeted” if he took up the post. Ambassador Ford who has been shunned by the embattled Syrian regime, has also been targeted by mainstream Egyptian media with state-owned Al Ahram describing him as “a man of blood” for allegedly “running death squads in Iraq” and “an engineer of destruction in Syria, Iraq and Morocco.” The independent El Watan newspaper has also warned that Ambassador Ford would “finally execute in Egypt what all the invasions had failed to do throughout history.”

The vicious media campaign against Ford followed critical remarks by a military spokesman opposing his possible nomination. “You cannot bring someone who has a history in a troubled region and make him ambassador, expecting people to be happy with it”, the spokesman had earlier said.

Rights activist and publisher Hisham Qassem told the Wall Street Journal last week that “Egyptian media often adopts the state line to avoid falling out of favour with the regime.”

Statements by US Senator John McCain who visited Egypt last week to help iron out differences between the ousted Muslim Brotherhood and the military, have further fuelled the rising tensions between Egypt and the US. McCain suggested that the June 30 uprising was a “military coup”, sparking a fresh wave of condemnation of US policy in the Egyptian press.

“If it walks like a duck, quacks like a duck, then it’s a duck,” Senator John McCain had said at a press briefing in Cairo. He further warned that Egypt was “on the brink of all-out bloodshed.” The remarks earned him the wrath of opponents of the toppled president who protested that his statements were “out of line” and “unacceptable.” The Egyptian press meanwhile has accused him of siding with the Muslim Brotherhood and of allegedly employing members of the Islamist group in his office.

The anti-Americanism in Egypt is part of wider anti-foreign sentiment that has increased since the January 2011 uprising and for which the media is largely responsible. Much like in the days of the 2011 uprising that toppled Hosni Mubarak, the country’s new military rulers are accusing “foreign hands” of meddling in the country’s internal affairs, blaming them for the country’s economic crisis and sectarian unrest. The US has also been lambasted for funding pro-reform activists and civil society organizations working in the field of human rights and democracy.

Ahead of a recent protest rally called for by Defense Minister Abdel Fattah El Sissi to give him “a mandate to counter terrorism”, the government warned it would deal with foreign reporters covering the protests as spies. As a result of the increased anti-foreign rhetoric in the media, a number of tourists and foreign journalists covering the protests have come under attack in recent weeks. There have also been several incidents where tourists and foreign reporters were seized by vigilante mobs looking out for “spies” and who were subsequently taken to police stations or military checkpoints for investigation. While most of them were quickly freed, Ian Grapel — an Israeli-American law student remains in custody after being arrested in June on suspicion of being a Mossad agent sent by Israel to sow “unrest.”

Attacks on journalists covering the protests and the closure of several Islamist TV channels and a newspaper linked to the Muslim Brotherhood do not auger well for democracy and freedoms in the new Egypt. The current atmosphere is a far cry from the change aspired for by the opposition activists who had taken to Tahrir Square just weeks ago demanding the downfall of an Islamist regime they had complained was restricting civil liberties and freedom of speech.

The increased level of xenophobia and anti-US sentiment could damage relations with America and the EU at a time when the country is in need of support as it undergoes what the new interim government has promised would be a “successful democratic transition.”

This article was originally published on 14 Aug, 2013 at indexoncensorship.org. Index on Censorship: The voice of free expression

2 Aug 2013 | Egypt, News and features, Politics and Society, Religion and Culture

When Defense Minister and Deputy Prime Minister Abdel Fattah El Sissi last week called on ‘loyal’ Egyptians to take to the streets to give him a mandate to confront what he called “terrorism,” tens of thousands of Egyptians rallied in major squares across the country, expressing their solidarity with the army chief they believed was acting to save Egypt from the scourge of civil war.

In Cairo’s eastern suburb of Nasr City meanwhile, thousands of Islamist supporters of deposed President Mohamed Morsi continued their sit-in outside a mosque, demanding Morsi’s re-instatement and denouncing what they describe as a “military coup against legitimacy.”

In the deeply polarized country, a seemingly unbridgeable gap between the two opposing rival camps and the intolerant attitude of you-are-either-with-us-or-against-us adopted by both Morsi’s opponents and his supporters, have left little room for neutrality. Yet, amidst the conflict and division, a third group has emerged — one whose members hope to re-unite Egyptians behind the common cause of “a free, democratic and civil Egypt.”

Made up of around 400 liberals, leftists and moderate Islamists, the so-called “Third Square” movement opposes both the military and the Muslim Brotherhood and is trying to promote a middle way amid the political turmoil, reminding Egyptians that they need to continue to work to achieve the goals of the January 2011 Revolution.

The opposition movement has adpoted the motto of “Down with all those who betrayed us: the Muslim Brotherhood, the army and Mubarak regime loyalists.” Since Islamists made sweeping gains in the 2012 parliamentary elections, the Muslim Brotherhood has often been accused by the liberal opposition of “stealing the revolution.” Meanwhile, during the transitional period when the SCAF was in power, revolutionary activists blamed the ruling military regime for the widespread human rights abuses — including the disappearance, detention and torture of hundreds of revolutionary activists — saying “the masks of the army generals running the country have dropped” and “the army and the people were never one hand.”

“The Muslim Brotherhood and the army are two faces of the same coin,” said activist/blogger Tarek Shalaby who joined the movement’s protest rally held at Sphinx Square in Cairo’s upscale neighborhood of Mohandessin last Sunday. “We neither want to be ruled by intolerant islamists whose aim is to establish a theocracy nor do we want a return to military dictatorship. ”

“No to the military junta; No to an Islamic state” and “Yes to a civil state,” read the banners raised by the activists at Sunday’s rally. The protesters also carried pictures of El Sissi and Morsi crossed out in red.

Shalaby and the other Third Square activists have used Facebook and Twitter to organize a series of protest rallies and mobilize support for their nascent movement. Posting humorous anecdotes that poke fun at the former rulers (SCAF and the Muslim Brotherhood), they also use the social media network to engage in lively discussions on the way forward for Egypt.

“We are trying to create a space where the January 2011 Revolution can stay alive and flourish. Our movement takes a firm stance against all counter-revolutionary forces . We hope to recruit more and more revolutionaries to the cause, paving the way for a political infrastructure that can lead to the democratic, civil society we aspire for,” said Shalaby.

Launched no more than a fortnight ago, the movement’s Facebook page has already attracted more than 8,300 fans and the number of followers is increasing. Yet, on the streets of Cairo, the voices of the Third Square activists are being drowned out by the cries of protesters in the two main opposing camps. Tamarod, the movement that organized the June 30 mass protests demanding Morsi’s ouster (and which now backs the interim government that replaced him) has accused the Third Square of being “counter-productive and divisive.”

“The movement is dividing the people. They are living in the past. Now is the time for consensus, we need to move forward,” Tamarod spokesman Mohamed Abdul Aziz told Voice of America. He also alleged the movement was “being led by Islamists” referring to former presidential candidate and Muslim Brotherhood member Abdel Moneim Abul Fottouh, whose Strong Egypt Party is heading the initiative.” It is a new face of the Muslim Brotherhood”, he told Daily News Egypt.

Pro-Morsi protesters camped out in Cairo’s northeastern suburb of Nasr City welcome the initiative, describing it as a “new front in the battle against military rule”.

“We welcome any movement that supports the goals of the January 2011 Revolution. It doesn’t bother us that the Third Square is against Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood. At least they oppose the military coup”, said Amany Kamal, a radio presenter working for the Egyptian Radio and TV Union, who recently helped establish a coalition of anti-coup journalists at Rab’aa where Morsi supporters are camped out.

Skeptics however, dismiss the significance of the movement, saying it can have little impact in effecting tangible change. “The Third Square is facing two very strong, well-organized adversaries — the military and the Muslim Brotherhood. Its chances of success are slim given the fact that it is outnumbered by the rival opposing camps”, said Amina Mansour, a photo journalist who participated in the anti-Morsi protests in Tahrir Square.

However, organizers of the movement say they will not be deterred by numbers alone. “We may be starting small but we are certain our movement will grow and spread throughout the country,” insisted Shalaby.

While he acknowledged that “the Third Square does not provide practical real-world solutions to the country’s political crisis,” he says “it’s a start and one of the many roads we need to walk down if we are to come out victorious.”

10 Jul 2013 | Egypt, Middle East and North Africa, Politics and Society

Image: Shutterstock

After the fall of Egypt’s Islamist president this month, security officials shut down media linked to the Muslim Brotherhood. With a history of biased media and an increasingly divided nation, the future Egypt looks grim. Shahira Amin reports

(more…)