2 Sep 2022 | BannedByBeijing, China, News and features

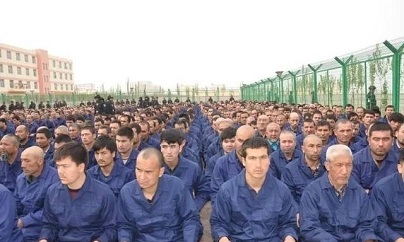

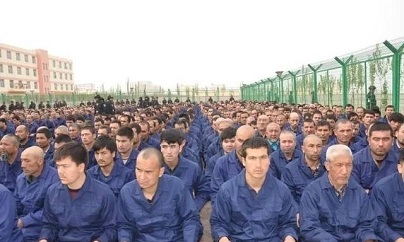

Detainees at a re-education camp in Xinjiang. Photo WeChat/Xinjiang Juridical Administration

“Serious human rights violations” have been committed in Xinjiang and the arbitrary and discriminatory detention of Uyghurs “may constitute…crimes against humanity” according to a controversial UN report that the Chinese government has been trying to quash.

The report also concludes that allegations of patterns of torture or ill-treatment, including forced medical treatment and adverse conditions of detention, as well as allegations of individual incidents of sexual and gender-based violence are “credible”.

What is also abundantly clear is that the report does not make mention of the word “genocide”, something that has left many campaigners unsatisfied.

The UN report goes so far as to push any mention of “suspicious deaths” occurring inside Xinjiang’s re-education centres into a footnote, saying that despite being presented with allegations on these by interviewees it had “not been possible to verify [them] to the requisite standard”. Restricting the ability of the UN to verify claims of human rights abuses is an effective method by which states, such as China, can effectively game the UN’s investigative process. By ensuring the body cannot access the evidence it needs, China can ostensibly shape what the UN can say without exerting any overt control or interference.

Last month it was revealed that the Chinese mission to the UN was lobbying to prevent the release of the report into human rights abuses in Xinjiang. The publication of the report, first commissioned in 2018, had been repeatedly delayed after having been completed in September 2021. Under tremendous pressure from other UN member states, the report was finally made available on 31 August in the last minutes of UN High Commissioner Michelle Bachelet’s term.

The release of the report has not been welcomed by the Chinese government. In its response to its publication, China’s mission to the UN said: “Based on the disinformation and lies fabricated by anti-China forces and out of presumption of guilt, the so-called ‘assessment’ distorts China’s laws and policies, wantonly smears and slanders China, and interferes in China’s internal affairs”.

The attempt to block the report’s publication may come as a shock to some but this incident is only the most recent attempt by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to silence Uyghurs both within and outside China and to discredit those who try to shine a light on their treatment. In the past, the UN has abdicated from its duty to challenge this global campaign against the Uyghurs. The publication of the report is a notable improvement on the UN’s poor track record. But the controversy surrounding the report’s release has left few critics of the UN optimistic about the ability of the organisation to defend Uyghurs in the future.

Michelle Bachelet meets Chinese president Xi Jinping in 2014, photo: Gobierno de Chile

The release of the Xinjiang report reflects a significant departure from the UN’s traditional soft-touch approach to managing its relationship with China. For example, earlier in 2022 Michelle Bachelet became the first UN High Commissioner to visit China in 17 years. While Bachelet praised China’s progress in labour standards and gender rights, she mentioned only in passing the treatment of Uyghurs, which according to credible reports, includes mass enslavement and systemic rape. Bachelet later admitted that her access to Uyghurs was severely restricted, ostensibly because of COVID-19 regulations, but to many her relative silence appeared to validate the Chinese government’s narrative surrounding events in Xinjiang. After her visit, The Global Times, a Chinese newspaper known for inevitably toeing the government line, ran an opinion piece praising Bachelet for changing her perspective on Xinjiang. The piece celebrated Bachelet’s adoption of CCP terminology – highlighting her use of “the term ‘Vocational Education and Training Centre’ instead of the so-called ‘re-education camp’” – and attributed her much-publicised decision not to run for a second term as High Commissioner to pressure she faced after speaking out in favour of China’s counter-terrorism measures.

Bachelet appeared to accept at face value claims that the re-education camps had “been dismantled” and appeared overly optimistic about “China’s stated aim of ensuring quality developed closely linked to developing the rule of law and respect for human rights”. While she expressed some half-hearted concern about the “lack of judicial oversight” in Xinjiang and mentioned Uyghurs she had met before her trip to China who had lost contact with their relatives, her condemnation of the treatment and mass detention of Uyghurs across the region was decidedly muted. Instead she praised China’s “tremendous achievements” in labour and gender rights, an insult to the victims of slave labour and sexual abuse in the camps. She concluded that “there is important work being done to advance gender equality, the rights of LGBTQI people or people with disabilities and all the people among other [groups]”.

China’s mission to the UN now says that the content of the report “is “entirely contradictory to the formal statement issued by [Bachelet]” following her visit. Just like the Global Times, China’s mission is falsely pointing to Bachelet’s Xinjiang trip as an exoneration of the CCP.

Bachelet herself emphasised that her visit “was not an investigation”, which begs the question why it happened in the first place. All her soft touch approach achieved was to grant the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) a significant PR win.

UN whistleblower Emma Reilly

To understand why UN officials like Bachelet have traditionally been so cautious about criticising China, Index spoke to Emma Reilly (left), an Irish former human rights officer at the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR). Reilly was fired in 2021 after blowing the whistle in 2017, revealing how the UN had for years been passing the names of Uyghurs set to testify before the UN to the Chinese government. Reilly explained to Index that Eric Tistounet from the OHCHR told concerned staff that “not giving them over would further Chinese distrust of the UN”.

One of the names on the list was Dolkun Isa who now resides in Germany. After the UN passed over his name to the Chinese authorities, his remaining family members who still resided in Xinjiang received a visit from the police. His parents later died in a re-education camp in circumstances that are still unclear. Reilly told Index that another person the UN exposed without their knowledge died upon their return to Xinjiang.

After the UN issued a medical report about Reilly, the Swiss police visited Reilly’s house and prevented her from attending a meeting about the issue she had exposed. In doing so, the UN effectively transformed the Swiss police into a tool of CCP censorship.

A tribunal was initiated to investigate Reilly’s case with the assistance of Rowan Downing QC, a former President of the UN Dispute Tribunal and an international war crimes judge. When it became clear that Downing’s ruling would not be favourable towards the UN, he was removed from his position. Downing compared this move to a coup.

Reilly told Index that the UN’s general reluctance to criticise the CCP is based on the misguided assumption that significant concessions need to be made to maintain a friendly relationship with the Chinese government. According to Reilly, it is commonly believed at the UN that increased engagement with the Chinese government will lead it to internalise global norms of human rights. But the opposite appears to be the case. In fact, the Chinese government has proven itself to be a powerful norm maker of its own as it becomes increasingly assertive in the UN.

Rosemary Foot’s book “China, the UN and Human Protection” seeks to explain the paradox of a China that is significantly more prominent in the UN system yet increasingly resistant to many of its central tenets. Most significantly, the Chinese government has sought to bolster the importance of sovereignty and undermine the universal nature of human rights.

For example, China had only used its security council veto power six times before the outbreak of the Syrian civil war. It then used it seven times to block resolutions condemning the Assad regime. The Chinese government believes that the treatment of Syrians, Uyghurs and other groups should be treated as “internal affairs” and economic growth should be seen as the principal means of improving human rights. As Kenneth Roth, the former executive director of Human Rights Watch, recently wrote, “if Beijing had its way, human rights would be reduced to a measurement of growth in gross domestic product”.

In her discussion with Index, Reilly expressed dismay that her case had received the most attention from right-leaning outlets sceptical of the UN project. Other outlets tended to focus on the treatment of whistleblowers rather than the behaviour she was uncovering and the necessity of systemic reform. Like many other UN whistleblowers, Reilly remains committed to the UN project and wants it changed, not abandoned.

Disempowering the UN (like the Trump administration tried to do by making significant cuts after its recognition of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel was rejected) will only empower the Chinese government to fill the vacuum. But the typical relationship the UN has had with the Chinese government swings the pendulum too far in the opposite direction. The UN must not allow itself to become a tool for China to censor its opponents but starving the UN of funds, undermining its mandate, and expecting it to reform is not a tenable solution that protects universal rights and targeted groups, including Uyghurs both in China and elsewhere.

Given the UN’s poor track record of endangering critics of the CCP, does the release of the Xinjiang report suggest the arrival of the kind of systemic reform that Reilly and others have called for?

Critics are sceptical that this recent development (while welcome) reflects a newly assertive United Nations. The next step would be for an independent investigation to be conducted into events in Xinjiang. Calls for such an investigation have also come from within the UN system after 50 UN human rights experts urged the Human Rights Council in 2020 to establish an independent UN mandate to monitor and report on human rights violations in China. According to the OHCHR’s own statement on this recommendation “unlike over 120 States, the Government of China has not issued a standing invitation to UN independent experts to conduct official visits.” However, two years later and progress has been glacial. Considering that the release of a report took almost three years once it was completed and was only possible after overwhelming pressure from other member states, any next step looks like an insurmountable challenge requiring consistent international solidarity and pressure at a time of growing international tension. The Chinese government cannot exert total influence over the UN to silence all of its critics but as demonstrated by the delays of the Xinjiang report, the UN process remains too easy for human rights abusers to impede.

Reilly remains critical of the UN. Now that the UN has officially recognised in its report that the CCP carries out “reprisals against Uyghur and other predominately Muslim minorities abroad in connection with their advocacy, and their family members in [Xinjiang]”, their continued smear campaign against her and refusal to condemn the policy she exposed is an increasingly untenable position.

There is also the question of how permanent the UN’s apparent change of strategy will be. It is notable that Bachelet only felt capable of releasing the report upon her departure from office when she would not have to face the consequences of her decision. Perhaps that now Bachelet is gone, her brief experiment with explicitly calling out the CCP’s human rights abuses will be replaced with business as usual.

Meanwhile, the global campaign to target Uyghurs both within and outside China continues

. Earlier this year, Index published a landmark report examining how the CCP has externalised its censorship and intimidation of Uyghurs even to those who have managed to escape to Europe in search of freedom and security. As highlighted by Reilly’s brave decision to blow the whistle, the CCP will use every mechanism and lever at its disposal to enforce its propaganda and target its perceived adversaries. Even though they now reside in Europe, Uyghurs continue to receive threats as do their families still living in Xinjiang. This report highlighted the lengths the CCP would go to strengthen its narrative and censor those brave enough to speak out, irrespective of where they are. It also revealed the inadequate response of European states to respond to this threat. Without a robust response, the CCP is emboldened to continue exporting its message to other countries and through international bodies like the UN. If the UN has only just reached the stage of officially recognising that this years long campaign is actually taking place, let alone taking active measures to stop it, who can Uyghurs rely on?

[Index made repeated requests to the United Nations for comment on this article but no replies were received at time of publication.]

To learn more about the censorship of Uyghurs in Europe, read Index’s Banned by Beijing report “China’s Long Arm”: https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2022/02/landmark-report-shines-light-on-chinese-long-arm-repression-of-ex-pat-uyghurs/

8 Jul 2022 | Americas, News and features, Peru

Peruvian president Pedro Castillo’s first year in office has been interesting to say the least. Since his election on 28 July 2021, he has faced two impeachment requests for alleged corruption for peddling influence to favour contractors in public works and “permanent moral incapacity”; he has survived both.

Unlike most media-hungry politicians, Castillo has gone silent – he hasn’t spoken to the press for more than 100 days. The last time was in February 2022 when he said “this press is a joke”. This silence seems to have no end in sight.

Gabriela García, a Peruvian journalist based in Lima with independent journalism portal Epicentro.TV, says Castillo has slammed the door closed on journalists in the country.

“The last time I think he was able to speak to journalists was during his campaign. And then began a lot of corruption in his circle with his ministers. He knows there are reasons to investigate him, so he is silent because he is afraid,” says García.

According to Garcia, Castillo is not fulfilling promises he made during the presidential campaign – to work for the poorest, that he would respect the press and would strengthen women’s rights. If anything, he is doing the exact opposite.

Like many around the world, Peruvians are facing a rising cost of living and many people are starving.

“I was not against him at the beginning of the campaign, I really thought it was an opportunity for the poorest. All decisions are made and rely on Lima, but we have another Peru that is forgotten. I am very disappointed with this”, says García, referring to the 195 provinces outside the capital.

Garcia’s disappointment is shared by fellow Peruvian journalist Luís Burranca.

“We are witnessing possibly the most corrupt government since Alberto Fujimori in the early 2000s,” says Burranca. “There are already four prime ministers who have held office in just a year and we have a former minister of transport and communications on the run from justice”. The former minister, Juan Silva, has been accused of irregular acts in public tenders for works and corruption and there is currently a 50,000 soles (£10,000) reward for information on his whereabouts.

The lack of communication with the president and the parliament itself makes the work of the press very difficult. Cameras are not accepted inside the Peruvian parliament, for example.

The relationship between press and presidents in Peruvian was previously stable, says Garcia. She has always worked closely with the government, while at the same time asking politicians difficult questions.

“Presidents might not like it, but they’d let us do our jobs,” she says. “Alejandro Toledo and Ollanta Humala were able to understand that they were the presidents, so they couldn’t insult anyone. They were more aware of their roles, about the presidential hierarchy.”

“Castillo doesn’t understand the work of the press. He doesn’t know why an independent press is so important. He thinks we have to be nice and easy. He’s lucky to be where he is, but he’s not prepared at all,” she says.

The difficulties in reporting on Peru’s politics is not confined to government – there is a far-right group in Peru today that is a particular problem for journalists and anyone on the other side politically. La Resistencia was created in 2018 by people who identify themselves as Christians and “defenders of the homeland”. They consider themselves “albertists”, as they seek to follow in the footsteps of Alberto Fujimori, president of Peru between 1990 and 2000 and who was convicted of crimes against humanity. La Resistencia’s ideology is based on authoritarianism, conservatism and opposition to communism and LGBT rights.

“They are untouchable and aggressive towards journalists,” says Garcia. “They are being investigated, but nothing has happened so far. We don’t know who gives them money. They say they are independent, but we don’t believe them. They are a problem for everyone.”

Despite the challenges, García believes that the independent press is growing stronger in the country.

“We are fighting for independence. We know it’s not the same thing as traditional television with a lot more money. We’re fighting with this [she shows her pen] and nothing else.”

Against this backdrop, Garcia is “more afraid than ever for democracy” in Peru.

“It’s a broken country, with far-right and far-left ideas colliding all the time. We are closer to the edge than ever before,” she said.

Roberto Uebel, professor of international relations at Brazil’s Superior School of Propaganda and Marketing (ESPM) of Porto Alegre in Brazil, believes a free press is vital for democracy.

“In Latin America, there has always been distrust from governments regarding the work of the press. The idea of a persecution that does not exist, this is very particular to the Latin American political context, a relationship of distrust between political actors and the press”.

Yet many leaders in Latin America engage with media. Nicaragua and Venezuela’s leftist regimes have a relationship with the press, albeit a state press. Chile and Argentina’s presidents have an open relationship with journalists.

“In the case of Peru, it is a more left-wing regime and does not have such a positive relationship. A hundred days without talking to the press,” says Uebel. “This dichotomy is very dangerous, the left regime is more open, right regimes are more closed. It depends much more on the political figure in power than on the type of regime”.

Whether Castillo will complete his full term is open to question.

Since Ollanta Humala left office in July 2016, most of his successors have faced repeated impeachment attempts, setting an average for Peruvian presidents of just one and a half years in office, says Uebel. Martin Vizcarra, for example, ruled the country between March 2018 and November 2020, stepping down after an impeachment process for “moral incapacity” and accused of influence peddling and corruption during his term as regional governor of Moquegua.

“The idea of a constant impeachment has already been institutionalised in Peru,” says Uebel.

García says she doesn’t believe that Castillo will finish his full term.

“All the ministers being investigated for corruption are close to him. We have food shortages in this poor country that has faced two years of a pandemic. The government is weakened.”

Faced with growing disillusionment in his abilities and the ever-present threat of impeachment, Castillo may not be able to remain silent forever.

14 Apr 2022 | News and features, Russia, Volume 51.01 Spring 2022, Volume 51.01 Spring 2022 Extras

The story of Index on Censorship is steeped in the romance and myth of the Cold War.

In one version of the narrative, it is a tale that brings together courageous young dissidents battling a totalitarian regime and liberal Western intellectuals desperate to help – both groups united in their respect for enlightenment values.

In another, it is just one colourful episode in a fight to the death between two superpower ideologies, where the world of letters found itself at the centre of a propaganda war.

Both versions are true.

It is undeniably the case that Index was founded during the Cold War by a group of intellectuals blooded in cultural diplomacy. Western governments (and intelligence services) were keen to demonstrate that the life of the mind could truly flourish only where Western values of democracy and free speech held sway.

But in all the words written over the years about how Index came to be, it is important not to forget the people at the heart of it all: the dissidents themselves, living the daily reality of censorship, repression and potential death.

The story really began not in 1972, with the first publication of this magazine, but with a letter to The Times and the French paper Le Monde on 13 January 1968. This Appeal to World Public Opinion was signed by Larisa Bogoraz Daniel, a veteran dissident, and Pavel Litvinov, a young physics teacher who had been drawn into the fragile opposition movement during the celebrated show-trial of intellectuals Andrei Sinyavsky and Yuli Daniel (Larisa’s husband) in February 1966. This is now generally accepted as being the beginning of the modern Soviet dissident movement.

The letter itself was written in response to the Trial of Four in January 1968, which saw two students, Yuri Galanskov and Alexander Ginzburg, sentenced to five years’ hard labour for the production of anti-communist literature.

The other two defendants were Alexey Dobrovolsky, who pleaded guilty and co-operated with the prosecution, and a typist, Vera Lashkova.

Ginzburg later became a prominent dissident and lived in exile in Paris, Galanskov died in a labour camp in 1972 and Dobrovolsky was sent to a psychiatric hospital. Lashkova’s fate is unclear.

The letter was the first of its kind, appealing to the Soviet people and the outside world rather than directly to the authorities. “We appeal to everyone in whom conscience is alive and who has sufficient courage… Citizens of our country, this trial is a stain on the honour of our state and on the conscience of every one of us.”

The letter went on to evoke the shadow of Joseph Stalin’s show-trials in the 1930s and ended: “We pass this appeal to the Western progressive press and ask for it to be published and broadcast by radio as soon as possible – we are not sending this request to Soviet newspapers because that is hopeless.”

The trial took place in a courthouse packed with Kremlin supporters, while protesters outside endured temperatures of 50 degrees below zero.

The poet Stephen Spender responded to the letter by organising a telegram of support from 16 prominent artists and intellectuals, including philosopher Bertrand Russell, poet WH Auden, composer Igor Stravinsky and novelists JB Priestley and Mary McCarthy.

It took eight months for Litvinov to respond, as he had heard the words of support only on the radio and was waiting for the official telegram to arrive. It never did.

On 8 August 1968, the young dissident outlined a bold plan for support in the West for what he called “the democratic movement in the USSR”. He proposed a committee made up of “universally respected progressive writers, scholars, artists and public personalities” to be taken not just from the USA and western Europe but also from Latin America, Asia, Africa and, ultimately, from the Soviet bloc itself. Litvinov later wrote an account in Index explaining how he had typed the letter and given it to Dutch journalist and human rights activist Karel van Het Reve, who smuggled it out of the country to Amsterdam the next day. Two weeks later, Soviet tanks rolled into Czechoslovakia to crush the Prague Spring.

On 25 August 1968, Litvinov and Bogoraz Daniel joined six others in Red Square to demonstrate against the invasion. It was an extraordinary act of courage. They sat down and unfurled homemade banners with slogans that included “We are Losing Our Friends”, “Long Live a Free and Independent Czechoslovakia”, “Shame on Occupiers!” and “For Your Freedom and Ours”.

The activists were immediately arrested and most received sentences of prison or exile, while two were sent to psychiatric hospitals.

Vaclav Havel, the dissident playwright and first president of the Czech Republic, later said in a Novaya Gazeta article: “For the citizens of Czechoslovakia, these people became the conscience of the Soviet Union, whose leadership without hesitation undertook a despicable military attack on a sovereign state and ally.”

When Ginzburg died in 2002, novelist Zinovy Zinik used his Guardian obituary to sound a note of caution. Ginzburg, he wrote, was “a nostalgic figure of modern times, part of the Western myth of the Russia of the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s, when literature, the word, played a crucial part in political change”.

Speaking 20 years later, Zinik told Index he did not even like the English word “dissident”, which failed to capture the true complexity of the opposition to the Soviet regime. “The Russian word used before ‘dissidents’ invaded the language was ‘inakomyslyashchiye’ – it is an archaic word but was adopted into conversational vocabulary. The correct translation would be ‘holders of heterodox views’.”

It’s perhaps understandable that the archaic Russian word didn’t catch on, but his point is instructive.

As Zinik warned, it is all too easy to romanticise this era and see it through a Western lens. The Appeal to World Public Opinion was not important because it led to the founding of Index. The letter was important because it internationalised the struggle of the Soviet dissident movement.

As Litvinov later wrote in Index: “Only a few people understood at the time that these individual protests were becoming a part of a movement which the Soviet authorities would never be able to eradicate.” Index was a consequence of Litvinov’s appeal; it was not the point of the exercise and there was no mention of a magazine in the early correspondence.

The original idea was to set up an organisation, Writers and Scholars International, to give support to the dissidents. It was only with the appointment of Michael Scammell in 1971 that the idea emerged to establish a magazine to publish and promote the work of dissidents around the world.

Spender and his great friend and co-collaborator, the Oxford philosopher Stuart Hampshire, were still reeling from revelations about CIA funding of their previous magazine, Encounter.

“I knew that [they]… had attempted unsuccessfully to start a new magazine and I felt that they would support something in the publishing line,” Scammell wrote in Index in 1981.

Speaking recently from his home in New York, Scammell told me: “I understood Pavel Litvinov’s leanings here. He understood that a magazine that was impartial would stand a better chance of making an impression in the Soviet Union than if it could just be waved away as another CIA project.”

Philip Spender, the poet’s nephew, who worked for many years at Index, agreed: “Pavel Litvinov was the seed from which Index grew… He always said it shouldn’t be anti-communist or anti-Soviet. The point wasn’t this or that ideology. Index was never pro any ideology.”

It has been suggested that Index did not mark quite such a clean break – it was set up by the same Cold Warriors and susceptible to the same CIA influence. In her exhaustive examination of the cultural Cold War, Who Paid the Piper, journalist Frances Stonor Saunders claimed Index was set up with a “substantial grant” from the Ford Foundation, which had long been linked to the CIA.

In fact, the Ford funding came later, but it lasted for two decades and raises serious questions about what its backers thought Index was for.

Scammell now recognises that the CIA was playing a sophisticated game at the time. “On one level this is probably heresy to say so, but one must applaud the skills of the CIA. I mean, they had that money all over the place. So, I would get the Ford Foundation grant, let’s say, and it never ever occurred to me that that money itself might have come from the CIA.”

He added: “I would not have taken any money that was labelled CIA, but I think they were incredibly smart.”

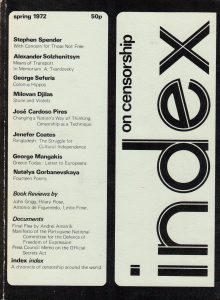

By the time the magazine appeared in spring 1972, it had come a long way from its origins in the Soviet opposition movement. It did reproduce two short works by Alexander Solzhenitsyn and poetry by dissident Natalya Gorbanevskaya (a participant in the 1968 Red Square demonstration, who had been released from a psychiatric hospital in February of that year). But it also contained pieces about Bangladesh, Brazil, Greece, Portugal and Yugoslavia.

Philip Spender said it was important to understand the context of the times: “There was a lot of repression in the world in the early ’70s. There was the imprisonment of writers in the Soviet Union, but also Greece, Spain and Portugal. There was also apartheid. There was a coup in Chile in 1973, which rounded up dissidents. Brazil was not a friendly place.”

He said Index thought of itself as the literary version of Amnesty International. “It wasn’t a political stance, it was a non-political stance against the use of force.”

The first edition of the magazine opened with an essay by Stephen Spender, With Concern for Those Not Free. He asked each reader of the article to say to themselves: “If a writer whose works are banned wishes to be published and if I am in a position to help him to be published, then to refuse to give help is for me to support censorship.”

He ended the essay in the hope that Index would act as part of an answer to the appeal “from those who are censored, banned or imprisoned to consider their case as our own”.

Since Index was founded, the Berlin Wall has fallen and apartheid has been dismantled. We have witnessed the “war on terror”, the rise of Russian president Vladimir Putin and the emergence of China as a world superpower.

And yet, if it is not too grand or presumptuous, the role of the magazine remains unchanged – to consider the case of the dissident writer as our own.

18 Mar 2022 | 50 years of Index, China, History, Ireland, Magazine, News and features, Philippines, United Kingdom, United States, Volume 51.01 Spring 2022 Extras

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The first issue of Index on Censorship magazine, in March 1972.

You may have heard that the 70s were different. In 1972, when the first issue of Index magazine was launched, no one knew that 20 years later there would be an influential economic bloc called the European Union. The Beatles’ had only just split. The World Trade Center in New York was being built, while Sir Edward Heath was the prime minister of the United Kingdom.

Fifty years on and some things remain. Queen Elizabeth’s reign goes on and celebrates its 70th anniversary in 2022. Dictatorships and censorship, which should be trapped in history books, continue to torment the lives of many. And as a result, Index on Censorship remains vigilant, defending freedom of expression and giving voice to those who are silenced.

As we celebrate our 50th anniversary, we go back in time and remember the remarkable events that happened in 1972.[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”1″][vc_column_text]January 30th: British soldiers shoot 26 unarmed civilians during a protest in Derry, Northern Ireland. Fourteen people were killed on this day known as “Bloody Sunday”. [/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”2″][vc_column_text]February 1st: Paul McCartney and the Wings release “Give Ireland back to the Irish” in the UK. It would be banned by the BBC, nine days later. [/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”3″][vc_column_text]February 5th: Airlines in the United States begin to inspect passengers and baggage. Tough to imagine that people traveled without any surveillance. [/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”4″][vc_column_text]February 17th: British Parliament votes to join the European Common Market. In 2020, the United Kingdom would leave the European Union. [/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”5″][vc_column_text]February 21st: Richard Nixon becomes the first US president to visit China, seeking to establish positive relations in a meeting with Chinese leader Mao Zedong, in Beijing.

Mao Zedong and Richard Nixon during Nixon’s historical visit to China in 1972. Photo: Ian Dagnall/Alamy

[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”6″][vc_column_text]March 15th: The Godfather, starring Marlon Brando and Al Pacino, premieres in New York. It wins Best Picture and Best Actor (Brando) at the 45th Academy Awards.

Al Pacino and Marlon Brando in the Godfather. The first film of one the most successful franchises of all time was released in 1972. Photo: All Star Library/Alamy

[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”7″][vc_column_text]June 18th: British European Airways Trident crashes after takeoff from Heathrow to Brussels, killing all 118 people on board. [/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”8″][vc_column_text]July 1st: Feminist magazine Ms, founded by Gloria Steinem, publishes its first issue, with Wonder Woman on the cover.[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”9″][vc_column_text]August 4th: Uganda dictator Idi Amin orders the expulsion of 50,000 Asians with British passports.

[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”10″][vc_column_text]September 4th and 5th: 11 members of the Israeli Olympic team are murdered by a Palestinian terrorist group in the second week of the 1972 Olympics in Munich.[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”11″][vc_column_text]September 21st: Philippines President Ferdinand Marcos declares martial law. In 2022, his son Ferdinand ‘Bongbong’ Marcos is running for president. [/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”12″][vc_column_text]October 13th: A flight from Uruguay to Chile crashes in the Andes Mountains. Passengers eat the flesh of the deceased to survive. Sixteen people are rescued two months later.[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”13″][vc_column_text]November 30th: BBC bans “Hi, Hi, Hi”, by Paul McCartney and The Wings, due to its drug references and suggestive sexual content. [/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”14″][vc_column_text]December 7th: Apollo 17 is launched and the crew takes the famous “blue marble” photo of the entire Earth.

The earth seen from the Apollo 17 spacecraft. Photo: NASA/Alamy

[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”15″][vc_column_text]December 28th: Kim Il-Sung takes over as president of North Korea. He’s the grandfather of the country’s current leader, Kim Jong-un. [/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”16″][vc_column_text]December 30th: US President Richard Nixon halts bombing of North Vietnam and announces peace talks in Paris, to be held in January 1973. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]