7 May 2015 | Denmark, Europe and Central Asia, mobile, News

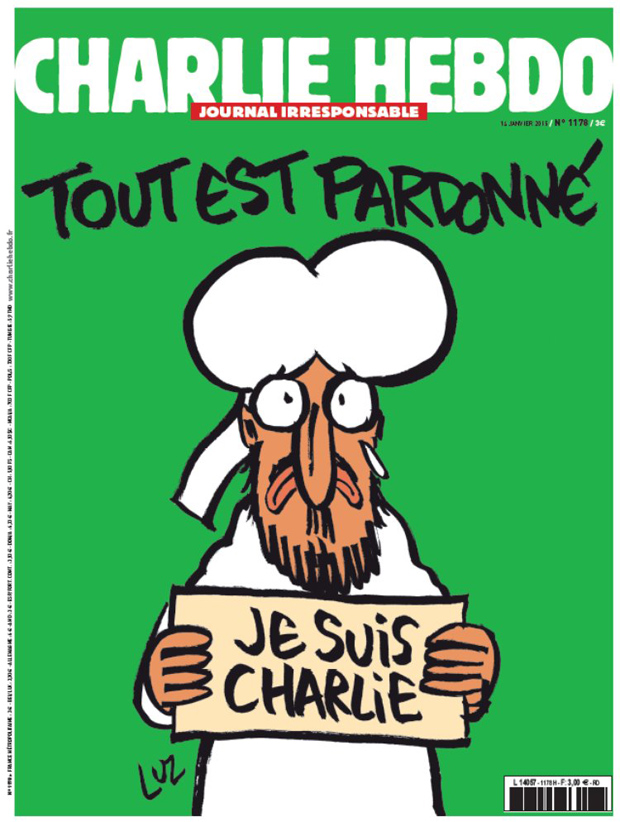

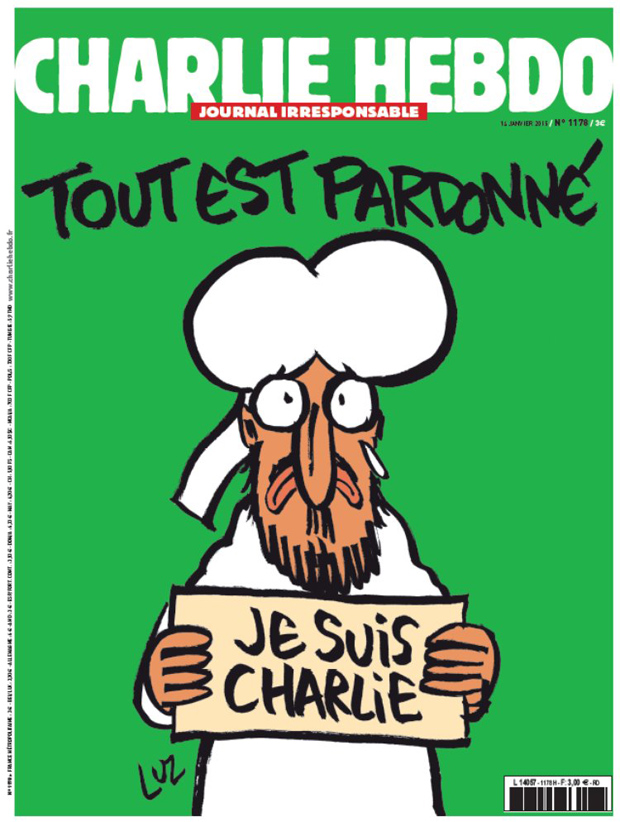

Tout est pardonne or All is forgiven, the first post attack cover of Charlie Hebdo

It’s now almost ten years since Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten published a set of cartoons, some of which (though by no means all) depicted the Islamic prophet Mohammed. Some were flattering, some were not. One mocked jihadist suicide bombers. Another showed a schoolboy called Mohammed calling Jyllands-Posten’s editors bigots.

The idea came after it was reported that a Swedish children’s author could not find someone to illustrate her book on the life of Mohammed. Flemming Rose of Jyllands-Posten decided to commission cartoonists to draw the apparently taboo figure.

As an exercise in taboo-busting, it was bound to be controversial. But controversial though some were (one showed the prophet as a scimitar wielding menace, another a figure with a bomb for a turban) they were not shocking enough for the Danish-based radicals who decided to make a campaign of the issue. In an astonishing act of chutzpah (there really is no other word), Ahmad Abu Laban decided to fill out a “dossier” on the cartoons with even more offensive characterisations, some of which had nothing to do with Mohammed at all. He and his colleague Ahmed Akkari took the dossier to the Middle East, apparently to prove the level of anti-Muslim hatred in Denmark. Chaos ensued. The rest, the usual line would go, is history. But that wouldn’t be true: the “rest” is very much the present, and perhaps pressing now more than at any time in the past 10 years.

One wonders if Ahmad Abu Laban quite knew what he was getting us all in to. Certainly, the man, who died in 2007, was of what is now a familiar figure in western Europe. The self-publicising Muslim spokesman: the go-to guy for a controversial quote for a press not quite sure of the heat of the flames with which they were playing. Omar Bakri Muhammad, for example, was first introduced to the British public as a ridiculous fantasist in Jon Ronson’s documentary The Tottenham Ayatollah. His proteges in al-Muhajiroun provided a steady flow of enjoyably ridiculous bogeymen such as Anjem Choudary and Abu Izzadeen, who in 2006 was given the main interview on BBC Radio 4’s Today programme. Subsequent news bulletins carried his warnings of “Muslim anger” as if he were some sort of pope, rather than a fringe figure with highly dubious links.

Everyone enjoyed these outrageous figures for a while, until we realised the damage they could do. Practically every home-grown jihadist in Britain has had dealings with al-Muhajiroun. The late Laban may have known of the chaos he was about to unleash on the Middle East in 2006 with his dossier, and indeed the world ever since. He may not. His former comrade Akkari repented in 2013, saying: “I want to be clear today about the trip: It was totally wrong. At that time, I was so fascinated with this logical force in the Islamic mindset that I could not see the greater picture. I was convinced it was a fight for my faith, Islam.”

Well good, but a little late now.

Since 2005 we have been embroiled in an absurd abysmal dream. Some people draw cartoons of a long-dead religious figure. Some other people decide this has offended some sacred, though undefined, law, and so they decide that the people who drew the cartoons must be killed. Repeat. What chronic stupidity.

But of course there’s more going on here. There is more than one reason to draw or publish Mohammed drawings: from plainly making a free speech point (as many publications did after the Charlie Hebdo murders), to anti-clericalism (a la Charlie itself), to deliberate antagonism towards Muslims (a la Pamela Geller). Not all Motoons are the same.

Nor are all responses on the same spectrum. There is a world of difference between the average Muslim who may be annoyed by a portrayal of Mohammed and a jihadist who takes it upon himself to find people who have drawn these portrayals and kill them or attempt to kill them.

This is the error that has plagued the debate for the past 10 years, and came to light again in the past few weeks with PEN’s awarding of a prize to Charlie Hebdo, and the attack on a Pamela Geller-organised rally in Texas which featured a “draw Mohammed” competition.

There has been an unwitting acceptance of several dangerous ideas, chief amongst them that in order to have respect for someone as a human being, one must respect all their beliefs, and observe their taboos. But as novelist and long-time PEN activist Hari Kunzru put it: “It is not solidarity with the oppressed to offer ‘respect’ to an idea just because it’s held by some oppressed people.”

Following from this is the idea that all expression that disrespects beliefs and taboos must be driven by bigotry and racism, and that to stand against bigotry and racism is to stand against any such expression. There is a sad irony in this failure to discriminate.

On the reverse of this, some Muslims feel that free speech is now something that is being used to batter them over the head, rather than protect them. This in itself is a failure of civil society: the moment we decide everyone with a certain background and set of beliefs can be put in the “Muslim” box is the moment we ensure that those who shout loudest about those beliefs — the “extremists” — are given status. Ahmad Abu Laban, for example, claimed that his Islamic Society of Denmark represented all Danish Muslims.

So now what? As we’re approaching 10 long years of this argument, is there hope for resolution any time soon? I fear not. There can be no accommodation between those who believe in the right to free expression and those who believe “blasphemy” should carry the death sentence.

In between, if it does prove impossible not to take sides, we can at least make sure our arguments are clear and our ears are listening.

This article was posted on 7 May 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

1 May 2015 | Denmark, European Union, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Macedonia, mobile, News, Poland, Spain, Turkey, Ukraine, United Kingdom

As we approach World Press Freedom Day, the right to freedom of expression will again be celebrated as an inalienable European value across the continent — by the public, the media and politicians alike. But to many, this will mean little more than engaging in a well trodden mental routine. We hardly consider the difficulties that freedom of expression faces in practice.

In the first part of 2015, more than a third of journalist killings in the word took place in two European countries; France and Ukraine. If it is true that Europe’s reactions to the Charlie Hebdo attack — the majority of them very emotional — were salubrious, they simultaneously gave rise to ambiguous situations. Many of the leaders that will on 3 May reaffirm their commitment free expression, supported the same message by taking part in the historic march in Paris on 11 January.

But upon seeing Angela Merkel, some were also reminded that Germany continues to treat blasphemy as a crime — as do Denmark, Spain, Poland and Greece, among others. Ireland, whose Enda Kenny was also in attendance, has a constitution which specifically mentions blasphemy and in 2010 enacted a new law against it. All these European countries defend themselves by saying that they do not apply their laws against “blasphemers”. That argument does not carry much weight when it comes to opposing those countries — Saudi Arabia, Iran, various Asian countries — that have tried to turn blasphemy into a universal crime recognised by the UN.

Spain’s Mariano Rajoy too marched in solidarity, but his government has taken steps to promote changes in the penal code that would “represent a serious threat to freedom of information, expression and the press”.

And what was Viktor Orban doing in Paris? The Hungarian president has reunified Hungary‘s public media so as to better bind them to his own party. Despite being the leader of an EU country, Orban has followed Vladimir Putin’s example. In this experimental model, the Andrei Sakharov Center and Museum is no longer ordered to close as it was in the old days, but rather fined 300,000 roubles (€5,000) for failing to register as a “foreign agent”. One day brings an announcement of compulsory registration for bloggers in Russia; another day, harassment against Russian and Hungarian NGOs perceived as “unpatriotic”.

Turkish Prime Minister Ahmet Davutohlu traveled to Paris, only to later label Charlie Hebdo’s post-attack issue a “provocation”. A reminder: Turkey is an EU candidate country where dozens of journalists have been sentenced to prison, and where various internet sites, including those that dared to reproduce some of Charlie Hebdo’s caricatures, have been blocked.

But also present at the march, were various representatives of European journalists — myself included. Just behind the Charlie Hebdo survivors, we carried a banner with the message “Nous sommes Charlie”.

Walking next to me was Franco Siddi, of the Italian National Press Federation. He talked to me about how imprisonment for defamation is still a possibility in Italy, though the European Court of Human Rights has ruled it a disproportionate punishment.

In my home country Spain too, this possibility of imprisonment remains, even if under Spanish jurisprudence freedom of expression consistently prevails over the demands of plaintiffs. In Italy, the situation is the same, yet my Italian colleagues point out that in 2014 alone, 462 journalists in the country were threatened with legal action for alleged acts of defamation. And while the current proposal for reform being considered foresees eliminating the possibility of jail time, it increases the potential fines.

This is not the only potential legal threat facing European journalists. Long before 9/11, there existed a reflexive habit of passing “urgent” laws under security pretexts, as in the UK during the most difficult years of the Northern Ireland conflict. The current model is the United States’ Patriot Act, which has recently been discussed in France. Meanwhile, in Britain and Spain are debating what free expression activists describe as “gag laws”. In Macedonia, the sentencing of the investigative journalist Tomislav Kezarovski to two years in prison under one of these security inspired laws stands out as a warning sign.

Against this worrying backdrop, across Europe journalists, freedom advocates, campaigners and even politicians are standing up for press freedom. When Gvozden Srecko Flego, member of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, recently highlighted the cases of Russia, Ukraine, Turkey and Azerbaijan as particularly problematic, he also suggested a countermeasure. He recommends “organising annual debates […], with the participation of journalists’ organisations and media outlets” in the respective parliaments of each state.

Media concentration, one of the most serious challenges to media pluralism and free expression in Europe, is being tackled. One proposal, which some international bodies have already accepted, would create a “Media Identity Card” requiring owners to publicly identify themselves and thus create an environment of more open and transparent media ownership.

When defending freedom of expression as a European value, we cannot allow ourselves to simply fall in into mental routines. This World Press Freedom Day we need both words and actions.

Paco Audije is a member of the Steering Committee of the European Federation of Journalists (EFJ)

World Press Freedom Day 2015

• Media freedom in Europe needs action more than words

• Dunja Mijatović: The good fight must continue

• Mass surveillance: Journalists confront the moment of hesitation

• The women challenging Bosnia’s divided media

• World Press Freedom Day: Call to protect freedom of expression

This column was posted on 1 May 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

19 Feb 2015 | News, United Kingdom

How does one avoid being a potential target for murder by a jihadist? If you’re Jewish, you probably can’t, unless you attempt to somehow stop being Jewish (though I suspect, much like the proto-nazi mayor of Vienna, Karl Lueger, IS reserves the right to decide who is a Jew).

Everyone else? Well, we can be a little quieter. We can, perhaps, not hold meetings with people who have drawn pictures of Mohammed. We can, perhaps, recognise that the right to free speech comes with responsibilities, as The Guardian’s Hugh Muir wrote. The responsibility to be respectful; the responsibility not to provoke; the responsibility not to get our fool selves shot in our thick heads.

This seemed to be the message coming after last weekend’s atrocity in Copenhagen. Oddly, I just found myself hesitating while typing the word “atrocity” there. Felt a little dramatic. Because already, amid the condemnations and what ifs? and what abouts? that have dogged us since this wretched year kicked into gear with the murders in Paris, already, the pattern seems set. Young Muslim men in Europe get guns, and then try, and for the most part succeed, in killing Jews and cartoonists, or people who happen to be in the same room as cartoonists. Then the condemnation comes, then the self-examination: what is it that’s wrong with Europe that makes people do these things? The things we definitely know are wrong are inequality and racism, so that’s where we focus our attentions. Europe’s past rapaciousness in the Middle East, or its recent and current interventions: these, on a societal level, are believed to be mistakes, so they too, must be examined (it could be argued that non-intervention, particularly in Syria, has been at least as much of a factor).

What else? Maybe we caused offence. Maybe we crossed a line when we allowed those cartoonists to draw those pictures. Maybe that’s it. We’ve offended two billion or so Muslims, and of course, some of them are bound to react more strongly than others. So we’d best be nice to them in future (we leave the implied “or else” hanging). And being nice means not upsetting people.

This is, as I’m fairly certain I’ve written before, a patronising and divisive way of looking at the world. Patronising because of the casual assumption that Muslims are inevitably drawn to violence by their commitment to their faith, and divisive both because it sets a double standard and because it entrenches the notion that Muslims are somehow outside of “us” in European society.

That divisiveness is not merely useful to xenophobes and Islamophobes. It is equally important in the agenda for many types of Islamist.

Take a small but instructive example. The BBC Two comedy Citizen Khan is possibly the most normal portrayal of Muslims British mainstream comedy has ever seen. The lead character started life as an absurd “community leader” in the brilliant BBC 2 spoof documentary Bellamy’s People, before morphing into an archetypal bumbling silly sitcom patriarch in his own successful show.

Citizen Khan is a classic British sitcom in which the family happen to be practicing Muslims. It is not cutting-edge comedy, boldly taking on racial and religious blah blah blah; it’s family entertainment.

Cause for celebration, surely, that practicing Muslims are being portrayed as normal people rather than radical weirdos? Not according to the risibly-titled Islamic Human Rights Commission, a small group of Ayatollah Khomeini fans who have nominated Citizen Khan for its annual Islamophobia award, claiming the show features “Muslims depicted as racist, sexist and backward. Obviously”. They don’t want to see Muslims on television as normal people, because that would undermine the division they seek to engender. I doubt any of the people at the IHRC who suggested Citizen Khan was Islamophobic are genuinely hurt or offended by the programme; if they are, it’s because it features a portrayal of Muslim people, by Muslim people, that they cannot control. It’s really got nothing to do with “offence”.

Likewise, I refuse to believe that the killers of Paris or Copenhagen have been sitting around stewing for years over “blasphemous” cartoons. To imagine that these murders took place because of perceived slight or offence is to cast them as crimes of passion. I don’t buy it. These were, at best in the eyes of the killers, legal executions for the crime of blasphemy, carried out because their interpretation of the law demanded that they do so.

The same interpretation of the law means that these men are allowed, mandated even, to kill Jews. So that is what they do.

However much cant we spill about “no rights without responsibilities” (that is, the preposterous “responsibility” not to offend), the fact that people are being murdered for who they are rather than what they did should make us realise that there is no responsibility we can exercise that will mitigate the core problem: a murderous totalitarian ideology has taken hold. It has territory, it has machinery, it has propaganda, and it has a certain dark appeal, just as totalitarian ideologies before have had. ISIS or Daesh or whatever you choose to call it is calling people to its cause. AQAP competes for adherents.

Some will point to the previous violent criminal records of the killers in Paris and Copenhagen and say “You see? They were mere thugs: the ideology barely comes into it.” But come on, who do you think the Brownshirts recruited? Bookish dentists? The fact that thugs are drawn to a thuggish ideology mitigates neither.

This week, Denmark’s only Jewish radio station went off air due to security concerns. This is where responsibilities before rights leads us. Shut up, keep quiet, and if something happens then it’s your fault for being irresponsible. Irresponsible enough to wish to practice your culture and religion freely. Irresponsible enough to “offend” murderers with your very existence. This line of thinking is not just cowardly, it is accusatory.

The correct answer to the request that we show responsibility with our rights, is, as revolutionary socialist James Connolly put it, “a high-minded assertion” of rights themselves. Not just the right to speak freely, but the right to live freely.

This article was posted on 19 February 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

16 Feb 2015 | Denmark, News

Site of the 14th February 2015 terrorist attack on a debate discussing blasphemy and artistic expression at Krudttønden in Copenhagen, Denmark. (Photo: Benno Hansen / Flickr)

While Saturday’s deadly attack in Copenhagen has many similarities to the one on French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo, one aspect sets it apart and marks a dangerous evolution in the assassin’s veto.

The attack on Charlie Hebdo targeted the magazine and its editors and journalists. So was the attack against Danish cartoonist Kurt Westergaard who in 2010 escaped an axe wielding Islamist by fleeing into a panic room. Other foiled attacks against Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten have been spectacular — one involved decapitating all journalists present and throwing their severed heads onto the street below — but also “limited” to the perceived offenders.

But when 22 year old Omar Abdel Hamid El-Hussein opened fire on café Krudttønden (in an area of Copenhagen where I was born and raised) he was attacking not only controversial Swedish cartoonist Lars Vilks. He was in fact targeting all the participants at a debate on free speech and Islam. Neither the film director who was killed nor any other participants (apart from Vilks) had anything to do with the cartoon of the Prophet Mohammed drawn by Vilks. For all we know some of the participants may have been offended by the cartoon and other material mocking Islam and would have expressed such feelings had they been given the chance.

That is after all the whole purpose of debate — differing viewpoints meeting and testing and probing each other’s strengths and weaknesses and thereby enlightening the public at large. By attacking such a public debate Abdel Hamid El Hussein and his enablers sent out a most disturbing message: to earn a death sentence for offending Islam, it is no longer necessary to actually make “offensive” expressions. Participating in a public debate on free speech and Islam will suffice.

That message is likely to have profound consequences for public debate on the very issues that are now more important for free societies to discuss than ever. For who can be expected to stage a debate on Islam and free speech, when it involves risking your life? Who would want to be part of the next panel involving Flemming Rose or Salman Rushdie, and who would be willing to act like sitting ducks in the audience? The few people brave enough to actually cross the red lines of the assassin’s veto will then have to think of the considerable costs involved in providing adequate security, and those participants willing to attend would then have to pay through the nose to risk their own lives.

One can only hope that these pernicious effects of the Copenhagen attack will cause what Salman Rushdie has labelled the “but-brigade” to reconsider the half baked defense of free speech that has become so characteristic since the Danish cartoon affair unleashed a global battle of values between free speech and religion. It should be clear that a free society cannot accommodate with special protection feelings of insult and offense that encompass the mere staging of a public debate on subjects of religion and politics. One also hopes that the victims of the Copenhagen shooting will be spared the shameful accusations of “racism” and “islamophobia” that were soon charged at Charlie Hebdo after the attack in Paris.

Despite the grim realities that confront free speech in contemporary Europe, I’m afraid that we must summon our courage and insist that no topics are off the table in public discourse and that murderers cannot be allowed to decide when, where and what we choose to discuss. The responsibility for crossing those red lines falls heavily on those of us who like to think of ourselves as the guardians of free speech.

Living in liberal democracies most of us will not have had much reason to fear for our safety as part of our free speech advocacy. But if we are serious about defending the right to offend, those of us heeding that call will have to stick our necks out too and get up on the podium next to the Flemming Roses, Salman Rushdies and Yahya Hassans of the world, armed with nothing more than the courage of our convictions.

Related:

Jodie Ginsberg: The right to free speech means nothing without the right to offend

Index on Censorship statement on blasphemy debate attack in Copenhagen

This guest post was published on 16 February 2015 at indexoncensorship.org