23 Jan 2018 | Azerbaijan, Cyprus, Europe and Central Asia, Latvia, Mapping Media Freedom, Media Freedom, media freedom featured, News, Serbia, United Kingdom

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project verifies threats, violations and limitations faced by the media throughout the European Union and neighbouring countries. Serious threats verified by the platform in January indicate that pressure has not let up in 2018. Here are five recent reports that give us cause for concern.

A Serbian minister announced on 12 January that he is suing the Crime and Corruption Reporting Network (KRIK), nominees for the 2017 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards, over the publications reporting on offshore companies and assets outlined in the Paradise Papers, a set of 13.4 million confidential documents relating to offshore investments leaked in November 2017.

Nenad Popovic, a minister without portfolio, was the main Serbian official mentioned in the leaked documents that exposed the secret assets of politicians and celebrities around the world. Popovic was shown to have offshore assets and companies worth $100 million.

“Serbian and Cypriot authorities have already launched lawsuits against various media workers so we’re particularly concerned that investigative outlets like KRIK are being sued for uncovering corruption of government officials,” Hannah Machlin, project manager, Mapping Media Freedom said. “Journalists reporting on corruption were repeatedly harassed, and in some cases murdered, in 2017, so going into the new year, we need to ensure that their safety is prioritised in order to preserve vital investigative reporting.”

KRIK was one of the 96 media organisations from over 60 countries that analysed the papers.

In December 2017 suspended senior state attorney Eleni Loizidou sued the daily newspaper Politis, seeking damages of between €500,000-2 million on the grounds that the media outlet breached her right to privacy and personal data protection. The newspaper had published a number of emails Loizidous had sent from her personal email account that implied Loizidou may have assisted the Russian government in the extradition cases of Russian nationals.

On 10 January the District Court of Nicosia approved a ban which forbids Politis from publishing emails from Loizidou’s account which she claims have been intercepted.

The ban will be in effect until the lawsuit against the paper is heard or another court order overrules it.

On 4 January, the Iranian embassy in London asked the United Kingdom Office of Communications to censor Persian language media based in the UK. The letter said the media’s coverage of the protests had been inciting people to “armed revolt”.

The letter primarily focused on BBC Persian and Manoto. BBC Persian has previously been criticised by Iranian intellectuals and activists for not distancing itself sufficiently from the Iranian government.

A journalist who works for the All-Russia State Television and Radio Broadcasting Company (VGTRK) was branded a threat to national security on 4 January and ordered to leave the country within 24 hours after being detained.

Olga Kurlaeva went to Latvia planning to make a film about former Latvian president Vaira Vike-Freiberga. Kurlaeva had interviewed activists critical of Latvia’s policies towards ethnic Russians and was planning on interviewing other politicians critical of Latvian policies.

Two days earlier, her husband, Anatoly Kurlajev, a producer for Russian TV channel TVC, was detained by Latvian police and reportedly later deported to Russia.

Elchin Mammad, the editor-in-chief of the online news platform Yukselis Namine, wrote in a public Facebook post on 4 January that he is being investigated for threatening and beating a newspaper employee.

Mammad wrote that the alleged victim, Aygun Amiraslanova, was never employed by Yukselis Namine and potentially does not exist. Mammad believes this is another attempt to silence his newspaper and staff.

Mammad was previously questioned by Sumgayit police in November about his work at the newspaper. The police told him that he was preventing the development of the country and national economic growth. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1516702060574-c4ac0556-7cf7-1″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

20 Dec 2017 | Mapping Media Freedom, Media Freedom, media freedom featured, News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text] This year saw 1,035 media freedom violations reported to Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom, a project that monitors media freedom in 42 countries, including all EU member states. To highlight the most pressing concerns for press freedom in Europe, Index’s MMF correspondents discuss the violations that stood out most.

This year saw 1,035 media freedom violations reported to Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom, a project that monitors media freedom in 42 countries, including all EU member states. To highlight the most pressing concerns for press freedom in Europe, Index’s MMF correspondents discuss the violations that stood out most.

Russia / 197 verified reports in 2017

“In November Russia adopted a new restrictive law against foreign media. It allows recognising foreign media as foreign agents, which makes them subjects of numerous additional checks and obliges them to mark the content as produced by a foreign agent. The vague and ambiguous wording means it applies to many outlets – from established media to email newsletters. Which media will be recognised as foreign agents will be decided by Russian Ministry of justice. However, US media such as Voice of America or Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty have already received warnings about possible restrictions on their work in Russia.” — Ekaterina Buchneva

Turkey / 132 verified reports in 2017

“Although 155 journalists are currently imprisoned in Turkey — almost all of them on trumped-up charges — the trial of journalist Nedim Türfent, who reported on security operations in Turkey’s Kurdish regions, is by far the worst violation as open experiences of torture at the hands of police officers were recounted by at least a dozen people in the case. This violation shows that torture is making a comeback in Turkey.” — Barış Altıntaş

More on Nedim Türfent’s case.

Belarus / 92 verified reports in 2017

“The mass detention of journalists on Freedom Day in March was indicative of the Belarusian authorities’ campaign launched in 2017 on preventing journalists from performing their professional duties. The situation was provoked by mass protests across Belarus against introducing presidential decree on “social parasites”, which imposes a tax on the unemployed amid increasing economic crisis. The authorities have shown their real attitude to freedom of speech through real hunting on independent journalists and bloggers that are blocked from access to information, detained, jailed, and fined.” — Volha Siakovich

Spain / 66 verified reports in 2017

“The referendum on the independence of Catalonia, north-east of Spain, provoked an avalanche of incidents against reporters. On 1 October 2017, on the day of referendum considered illegal by the Spanish Constitutional Court, various journalists were assaulted during police intervention in polling stations. Spanish public television RTVE was biased in favour of Spanish unity while Catalan public television TV3 was biased in favour of the independence. In the aftermath of the referendum, many reporters on the ground suffered insults and assaults usually during street rallies. Unionist protesters used to insult and assault Catalan media. Catalunya Radio glass door was smashed and TV3 car window broken. Catalan protesters chanted “Spanish press manipulators” during Spanish televisions live coverage and Crònica Global website headquarters vandalised with spray paints and posters. The Catalan political question brought a wave of intimidation against journalists, never seen in such numbers and scale in recent years.” — Miho Dobrasin

Italy / 57 verified reports in 2017

“In 2017 Italian journalists experienced a high level of conflict with the judiciary. Journalists are constantly possible targets of law enforcement raids, also in breaching the privacy of journalists’ sources. In July, Il Fatto Quotidiano journalist Marco Lillo’s house was searched because he published a scoop concerning the investigation on people close to Matteo Renzi, prime minister at time time, for a case of corruption at the most important contracting authority in Italy: Consip. Last but not least, Il Sole 24 Ore journalist Nicola Borzi had seized his computer and archives by the law enforcement because he revealed a “secret of State”, without any formal charge against the journalist. These events show how hard is making scoops in Italy. Moreover, journalists are constantly targeted with lawsuits, frequently used as threats against freelancers. Nowadays the big unsolved issue for Italian journalism is at court.” — Lorenzo Bagnoli

France / 54 verified reports in 2017

“In February, presidential candidate Fillon smeared media outlets who covered alleged corruption case. This was an important moment in the treatment of the media in France. When accused of corruption, conservative presidential candidate François Fillon refused to step down and chose to attack the media and journalists. Journalists covering his campaign saw their working conditions deteriorate and had supporters insulting and attacking them.” — Valeria Costa-Kostritsky

Azerbaijan / 47 reports in 2017

“While there on-going violations of press freedom in Azerbaijan such as the jailing of journalists, office raids, bogus charges and other forms of persecution of journalists, I chose the blocking of opposition and independent news websites in March because it is a sign of further deterioration of media freedom in Azerbaijan. If before there were deliberate slowdowns or DDoS attacks, changes in legislation give full authority to the government institutions wanting to shut down or limit access to the flow of independent and alternative news.” — Arzu Geybullayeva

Croatia / 33 verified reports in 2017

“In September, around 20 members of the Autochthonous Croatian Party of Rights (A-HSP), a far-right political party, which is led by Drazen Keleminec, burned a copy of weekly newspaper Novosti, regional broadcaster N1 reported. This is another example where nationalistic and conservative narratives are endangering media freedom. In this particular case a right-wing political party is targeting the others, in this case the others is an ethnically and linguistically minority weekly, describing them as enemies of the state. The widespread narrative that has resulted in several severe media freedom infringements in this EU country.” — Ilcho Cvetanoski

Macedonia / 27 verified reports in 2017

“During the April’s storming of the Assembly building in the capital Skopje, 23 media workers were physically assaulted, threatened or barred from reporting at the scene. This case perfectly exemplifies what happens when political elites intentionally demonize and dehumanize media workers that are critically observing theirs work by describing them as traitors and foreign mercenaries. In the eyes of the common people, they instantly became a legitimate target. This is a widespread trend in Southeast Europe.” — Ilcho Cvetanoski

Bosnia and Herzegovina / 21 verified reports in 2017

“The case of Dragan Bursac is one of the many cases in Southeast Europe where journalists/media workers are threatened/attacked for challenging the mainstream nationalistic narrative. Namely, he was critical on the fact that a military leader, accused of committing war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), is celebrated as a hero by the politicians and media.” — Ilcho Cvetanoski

Germany / 20 verified reports in 2017

“It is extremely concerning that journalists were assaulted and intimidated when reporting on protests in Hamburg. Journalists are there to do their job and it is important that they are able to tell the world what is happening at protests such as the ones in Hamburg.” – Joy Hyvarinen

Hungary / 20 verified reports in 2017

“There is an important change of tactics regarding censorship and defaming independent media in Hungary: instead of attacking the outlets critical to the government, the vast pro-government media started smearing individual journalists, trying to intimidate and discredit the few critical voices who are left in Hungary.” — Zoltan Sipos

Romania / 16 verified reports in 2017

“The national news agency AGERPRES might lose its independence after a draft law enabling the political majority to dismiss the director-general was passed by the chamber of deputies in Romania. If passed in the senate as well, such a provision would have the same impact as on the management of the Romanian Radio Broadcasting Corporation (SRR) and the Romanian National Television Corporation (SRTV): following each election, the SRR and SRTV administration boards can be dismissed before the end of their mandates to reflect the new political forces.” — Zoltan Sipos

United Kingdom / 17 verified reports in 2017

“In the United Kingdom, after the Grenfell tower fire, which claimed 71 deaths, Kensington and Chelsea council tried to ban journalists from attending their first council meeting. Five media organisations had to challenge this legally to gain access. This was a very important case illustrating how difficult it was to gain access and to expect accountability from the organisation which ran the council block.” — Valeria Costa-Kostritsky

Sweden / 15 verified reports in 2017

“The systematic campaign to smear and misrepresent journalists by Granskning Sverige was symptomatic of a wider attack on the legitimacy of liberal and left media by Sweden’s far-right movement, but the campaign detailed by the reporters at the Eskilstuna-kuriren newspaper was orchestrated and unlike anything seen before in the country.” — Dominic Hinde

Greece / 13 verified reports in 2017

“In February 2017, two journalists were harassed by far-right wing protesters, preventing refugee children from attending classes. This is very important, because it shows that although Greece’s economic and refugee crisis seem to have calmed down in the last year, the support for far-right wing organisations doesn’t show any sign of shrinking. This also concerns journalists in Greece, whose safety is in danger every day.” — Christina Vasilaki

The Netherlands / 12 verified reports in 2017

“The Netherlands is considered to be one of the countries where media freedom is widely protected. However, cases like the rape threats levelled at a journalist in May show that media workers are subjected to all sorts of threats. In this case it were rape threats by a popular right-wing weblog. This creates an atmosphere in which it’s conceived normal to use comments and social media to discredit and threaten a journalist. It also highlights the dangers and risks that female journalists face.” — Mitra Nazar

Bulgaria / 11 verified reports in 2017

“In November, it became known that members of an organised crime group from Vratsa planned to murder Zov News website publisher Georgi Ezekiev. The increase of violent incidents and serious threats towards journalists in 2017 is alarming in Bulgaria, a country that already has the worst press freedom status in the European Union.” — Zoltan Sipos

Serbia / 11 verified reports in 2017

“Serbia’s free media had a dark year with many incidents, threats and violence coming towards them. In May, journalists were assaulted during clashes at the presidential inauguration. This is just one of many cases, but it clearly demonstrates just how critical the state of the media is because they happened during the presidential inauguration. The assaults were committed by supporters of the government with a lot of police around. The impunity these assaulters meet is worrying for the lack of condemnation by authorities and the message they clearly want to send to critical journalists.” — Mitra Nazar

Malta / 8 verified reports in 2017

“The most worrying incident regards the murder of anti-corruption, investigative journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia. While this murder gripped the attention of international media and European authorities including the European Commission and Parliament, it is still shocking for every journalist that in a democratic, EU country, journalists’ lives could be in danger because they are doing their job, exposing high-level corruption in political, business and criminal elites.” — Christina Vasilaki

Kosovo / 6 verified reports in 2017|

“Kosovo’s media have been shaken up by two attacks on Insajderi investigative journalists. Insajderi is home to the best investigative journalists in the country, covering corruption and crime topics that nobody else dares to touch. Journalist Parim Olluri was beaten up outside his home in Pristina on 16 August. He needed medical assistance in a hospital. Nobody has been held responsible for the attack. Two months later, his colleague Vehbi Kajtazi was hit on the head in a cafe in downtown Pristina on 13 October. One person was arrested on the spot. We are talking about two violent incidents to Insajderi journalists within a period of three months. This shows that Kosovo’s journalists continue to face violence, even in very public places like cafe’s and neighbourhoods they live. For this reason there are just a few brave journalists who dare to touch sensitive topics, which is a worrying sign for the future of journalism and truth finding in the youngest country in Europe.” — Mitra Nazar

Montenegro / 6 verified reports in 2017

“Attack on journalist’s property is one of most common ways of intimidation. This is not only case for Montenegro, but also for all other countries in the region. What is striking is that intentional setting on fire of journalist’s vehicles is one of most common ways of limitation of media freedom in Montenegro. In recent years there have been several burnt vehicle in this small EU candidate country.” — Ilcho Cvetanoski

Portugal / 5 verified reports in 2017

“Similarly to what’s happening in other countries, Portugal has seen a rise of questioning towards journalism, those who work in the media industry and their work. Besides motivating a new and stimulating debate between journalists and their readers/viewers/listeners, this has also opened the gates to instances of abuse, cyberbullying and slander. The most significant example of that is that of Público’s journalist Margarida Gomes, whose work ethic was put in question by Facebook groups and public officials, who both used false information regarding her personal life to denigrate her work.” — João de Almeida Dias

Latvia / 3 verified reports in 2017

“In Latvia it was a quiet year for press freedom. However, the sudden and swift dismissal of Sigita Roķe, the head of public service Latvian Radio for alleged economic irregularities was seen as a pretext for dismissing her for efforts to disengage the radio from sponsorship agreements with the city of Ventspils, whose politically influential mayor has is on trial for money laundering and corruption. The dismissal raised questions about the political neutrality of Latvia’s media watchdog, the National Electronic Mass Media Council.” — Juris Kaza

Ireland / 3 verified reports in 2017

“Compared to the long list of countries in Europe where it is getting progressively dangerous for reporters to do their work, the situation in Ireland is relatively benign. There are renewed concerns over source protection, and the strict libel regime. However, the most serious concern is regarding media ownership. Index on Censorship published a detailed report on this in August 2017. One significant media takeover – Independent News and Media buying up Celtic Media – fell through after the Government ordered a statutory investigation following objections.” — Flor Mac Carthy

Estonia / 3 verified reports in 2017

“In March, journalists for Estonia’s largest daily in circulation Postimees, sent a letter to the owners and managers to complain about interference with editorial freedom. This event is a disturbing example of the interference attempts from media owners and advertisement department that had grown to the level that journalists of a daily, that prides itself with a long history and high-quality content, had to resort to an unprecedented united protest letter to fight it. Interference in journalistic decision making and content from outside or inside sources is in general the worrisome threat.” — Helle Tiikmaa

Belgium / 2 verified reports in 2017

“In Belgium, a journalist who had published a story on surveillance in Bruxelles’ metro was interrogated on her sources by the police, in clear breach of the principle of sources confidentiality. The case also reminds us of the risk for journalists covering surveillance.” — Valeria Costa-Kostritsky

Denmark / 2 verified reports in 2017

“The killing of Kim Wall by the inventor and entrepreneur Peter Madsen was a headline news event around the world. Stabbed to death and dumped at sea whilst interviewing Madsen on board his home-built submarine, her body was recovered after an extensive marine search. Although not typical of any wider trend, her murder was so brutal it raised significant questions about the safety and ethics of female freelancers working alone without support or safeguards.” — Dominic Hinde

Finland / 2 verified reports in 2017

“In March the Finnish government introduced restrictive changes to the functioning of the public broadcasting company Yle, which entailed putting the state-owned company more firmly under politicians’ decision-making power. The proposal was driven by the True Finns, a nationalist party that have repeatedly complained about Yle’s liberal views and non-sceptical approach to ‘multicultural Finland’. In the official briefing, stated the following: “The proposal is to strengthen the role of the Administrative Council so that they can decide on Yle’s journalistic strategy and regulate the permanent expert consultation process”. The council referred is mainly composed of politicians. — Katariina Salomäki

Iceland / 1 verified report in 2017

“Iceland has been rocked by political scandals and collapsing governments twice in the space of a year. In October it came to light that the prime minister had used financial confidentiality legislation to stop the investigative newspaper Stundin from publishing details of his offshore financial dealings in the run-up to the 2008 financial crash. Iceand’s main newspaper Morgunbladid is controlled by another former Prime Minister, also a member of the powerful Icelandic independence party, and Stundin has consistently sought to expose the Icelandic financial and political elite where other titles have remained silent.” — Dominic Hinde[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Mapping Media Freedom” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fmappingmediafreedom.org%2F%23%2F|||”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-times-circle” color=”black” background_style=”rounded” size=”xl” align=”right”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

Since 24 May 2014, Mapping Media Freedom’s team of correspondents and partners have recorded and verified more than 3,700 violations against journalists and media outlets.

Index campaigns to protect journalists and media freedom. You can help us by submitting reports to Mapping Media Freedom.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Don’t lose your voice. Stay informed.” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship is a nonprofit that campaigns for and defends free expression worldwide. We publish work by censored writers and artists, promote debate, and monitor threats to free speech. We believe that everyone should be free to express themselves without fear of harm or persecution – no matter what their views.

Join our mailing list (or follow us on Twitter or Facebook) and we’ll send you our weekly newsletter about our activities defending free speech. We won’t share your personal information with anyone outside Index.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][gravityform id=”20″ title=”false” description=”false” ajax=”false”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row]

26 Oct 2017 | Mapping Media Freedom, media freedom featured, News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Wall Street Journal reporter Ayla Albayrak

Last week, a reporter for the Wall Street Journal was convicted of producing “terrorist propaganda” in Turkey and sentenced to more than two years in prison.

Ayla Albayrak was charged over an August 2015 article in the newspaper, which detailed government efforts to quell unrest among the nation’s Kurdish separatists, “firing tear gas and live rounds in a bid to reassert control of several neighborhoods”.

Albayrak was in New York at the time the ruling was announced and was sentenced in absentia but her conviction forms part of a growing pattern of arrests, detentions, trials and convictions for journalists under national security laws – not just in Turkey, the world’s top jailer of journalists, but globally.

As security – rather than the protection of fundamental rights and freedoms – becomes the number one priority of governments worldwide, broadly-written security laws have been twisted to silence journalists.

It’s seen starkly in the data Index on Censorship records for a project monitoring media freedom in Europe: type the word “terror” into the search box of Mapping Media Freedom and more than 200 cases appear related to journalists targeted for their work under terror laws.

This includes everything from alleged public order offences in Catalonia to the “harming of national interests in Ukraine” to the hundreds of journalists jailed in Turkey following the failed coup.

This abusive phenomenon started small, as in the case of Turkey, with dismissive official rhetoric that was aimed at small segments — like Kurdish journalists — among the country’s press corps, but over time it expanded to extinguish whole newspapers or television networks that espouse critical viewpoints on government policy.

While Turkey has been an especially egregious example of the cynical and political exploitation of terror offenses, the trend toward criminalisation of journalism that makes governments uncomfortable is spreading.

Mónica Terribas, journalist for Catalunya Rádio

In Spain, the Spanish police association filed a lawsuit against Mónica Terribas, a journalist for Catalunya Rádio, accusing her of “favouring actions against public order for calling on citizens in the Catalonia region to report on police movements during the referendum on independence.

The association said information on police movements could help terrorists, drug dealers and other criminals.

Undermining state security is a growing refrain among countries seeking to clamp down on a disobedient media, particularly in countries like Russia. In December 2016, State Duma Deputy Vitaly Milonov urged Russia’s Prosecutor General to investigate independent Latvia-based media outlet Meduza’s on charges of “promoting extremism and terrorism” for an article published the day before.

The piece written by Ilya Azar entitled, When You Return, We Will Kill You, documents Chechens who are leaving continental Europe through Belarussian-Polish border and living in a rail station in Brest, a border city in Belarus. Deputy Milonov said he considers the article a provocation aimed at undermining unity of Russia and praising terrorists.

German journalist Deniz Yucel

In Turkey, reporting deemed critical of the government, the president or their associates is being equated with terrorism as seen in the case of German journalist Deniz Yucel who was detained in February this year.

Yucel, a dual Turkish-German national was working as a correspondent for the German newspaper Die Welt. He was arrested on charges of propaganda in support of a terrorist organization as well as inciting violence to the public and is currently awaiting trial, something that could take up to five years.

Ahmed Abba

Outside of the European region, journalists regularly fall foul of national security laws. In April, journalist Ahmed Abba was sentenced to 10 years behind bars by a military tribunal in Cameroon after being convicted of non-denunciation of terrorism and laundering of the proceeds of terrorist acts. Accompanying the decade-long sentence was a fine of over $90,000 dollars. Abba, a journalist for Radio France International, was detained in July of 2015. He was tortured and held in solitary confinement for three months.

The military court allegedly possessed evidence against Abba, who was barred from speaking with the media during his trial, which they found on his computer. Among the alleged evidence was contact information between Abba and the Islamist terrorist group Boko Haram. Abba, who was in the area to report on the Boko Haram conflict, claimed he obtained the information that was discovered on his phone from various social media outlets with the intent of using them for his report.

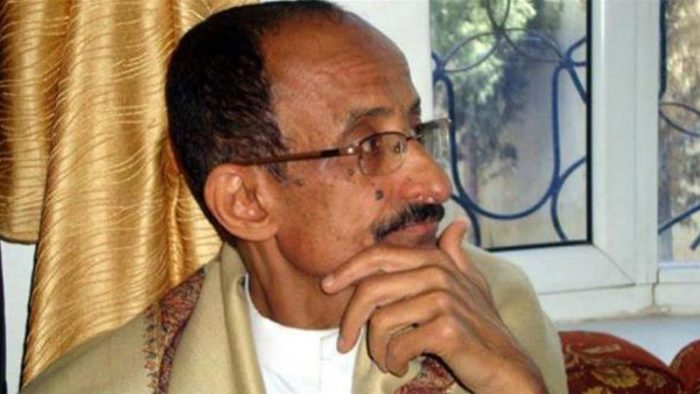

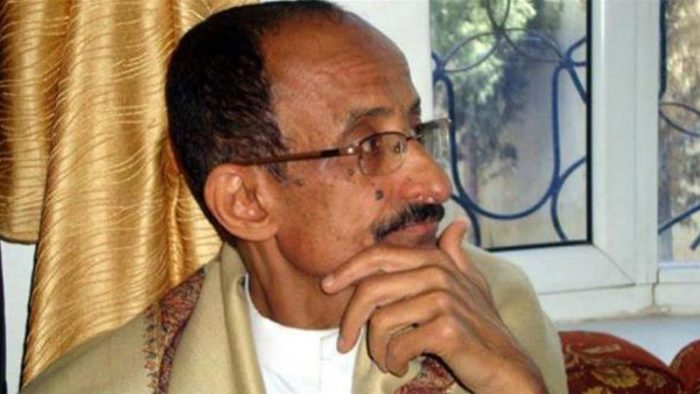

Yemeni journalist Yahya Abduraqeeb al-Jubaihi

Yemeni journalist Yahya Abduraqeeb Al-Jubaihi was sentenced to death earlier this month for allegedly serving as an undercover spy for Saudi Arabian coalition forces. Al-Jubaihi, who has worked as a journalist for various Yemeni and Saudi Arabian newspapers, has been held in a political prison camp ever since he was abducted from his home in September 2016.

Al-Jubaihi is the first journalist to be sentenced to death in Yemen following a trial that many activists believe was politically motivated because of Al-Jubaihi’s columns criticising Houthis.

Journalist Narzullo Akhunjonov

Increasingly, governments are turning to Interpol to target journalists under terror laws. Turkey has filed an application to seek an Interpol arrest warrant for Can Dündar, demanding the journalist’s extradition. In September, Uzbek journalist Narzullo Okhunjonov was detained by authorities in Ukraine following an Interpol red notice.

Uzbek authorities have issued an international arrest warrant on fraud charges against Okhunjonov, who had been living in exile in Turkey since 2013 in order to avoid politically motivated persecution for his reporting.

And governments are also using terror laws to spy on journalists. In 2014, the UK police admitted it used powers under terror legislation to obtain the phone records of Tom Newton Dunn, editor of The Sun newspaper, to investigate the source of a leak in a political scandal. Police powers under the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act, which circumvents another law that requires police to have approval from a judge to get disclosure of journalistic material.

No laughing matter

The Sun editor Tom Newton Dunn

Even jokes can land journalists in trouble under terror laws. Last year, French police searched the office of community Radio Canut in Lyon and seized the recording of a radio programme, after two presenters were accused of “incitement to terrorism”.

Presenters had been talking about the protests by police officers that had recently been taking place in France. One presenter said: “This is a call to people who people who killed themselves or are feeling suicidal and to all kamikazes” and to “blow themselves up in the middle of the crowd”.

One of the presenters was put under judicial supervision and was forbidden to host the radio programme until he appeared in court.

Radio Canut journalist Olivier Combi explained that the comment was ironic: “Obviously, Radio Canut is not calling for the murder of police officers, as it was sometimes said in the press”, he said. “Things have to be put back in context: the words in question are a 30 seconds joke-like exchange between two voluntary radio hosts…Nothing serious, but no media outlet took the trouble to call us, they all used the version of the police.”

Fighting back to protect sources

Two Russian journalists — Oleg Kashin and Alexander Plushev — are pushing back, Meduza reported. Kashin and Plushev filed the lawsuit challenging Russia’s Federal Security Service’s demands that instant messaging apps turn over encryption keys for users’ private communications, which is being driven by Russia’s anti-terror legislation. The court rejected the suit with the judge reportedly found that the government’s demands do not infringe on Plushev’s civil rights.

The journalists had contended that the FSB’s demand violated their right to confidential conversations with sources. Kashin said that in his work as a journalist he had come to rely on apps such as Telegram to conduct interviews with politicians.

Human rights organisation Agora is representing Telegram in a separate case against the FSB, which has fined the app company for failing to comply with its demands.[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”96229″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/10/turkish-injustice-scores-journalists-rights-defenders-go-trial/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

About 90 journalists, writers and human rights defenders will appear before courts in the coming days[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”96183″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/10/interpol-the-abuse-red-notices-is-bad-news-for-critical-journalists/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Since August, at least six journalists have been targeted across Europe by international arrest warrants issued by Turkey, Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Mapping Media Freedom” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-times-circle” color=”black” background_style=”rounded” size=”xl” align=”right”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

Since 24 May 2014, Mapping Media Freedom’s team of correspondents and partners have recorded and verified 3,597 violations against journalists and media outlets.

Index campaigns to protect journalists and media freedom. You can help us by submitting reports to Mapping Media Freedom.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Don’t lose your voice. Stay informed.” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship is a nonprofit that campaigns for and defends free expression worldwide. We publish work by censored writers and artists, promote debate, and monitor threats to free speech. We believe that everyone should be free to express themselves without fear of harm or persecution – no matter what their views.

Join our mailing list (or follow us on Twitter or Facebook) and we’ll send you our weekly newsletter about our activities defending free speech. We won’t share your personal information with anyone outside Index.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][gravityform id=”20″ title=”false” description=”false” ajax=”false”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row]

18 Aug 2017 | News, Youth Board

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship has recruited a new youth advisory board to sit until December 2017. The group is made up of young students, journalists and researchers from four continents.

Each month, board members meet online to discuss freedom of expression issues around the world and complete an assignment that grows from that discussion. For their first task the board were asked to write a short post about a pressing freedom of expression issue from their countries of residence.

Sean Eriksen – Brisbane, Australia

Eriksen is a 21-year-old Arts/Law student majoring in history and international relations

Notwithstanding the aphorism that ‘if free expression is to mean anything then it must protect unpopular opinions’, censorship is most tolerable at the fringes; and it is a mark of social progress that bigotry is considered so unpopular that many countries have tried to legislate it out of existence. But the suggestion that hate speech laws represent a positive cultural development does not endear them to those who believe free expression is inherently sacrosanct.

Section 18C(1)(a) of Australia’s federal Racial Discrimination Act 1975 prohibits acts that are reasonably likely to ‘offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate another person or group of people’ based on their race, colour, or national or ethnic origin. This allows administrative review and ultimately litigation, giving judges a wide capacity to make rulings on acceptable public discourse.

Defenders of the law claim that sufficient legislative exemptions protecting artists, commentators and academics exist elsewhere in the legislation, but in practice the standard for offence has not been particularly high. Most famously in Eatock v Bolt, articles by a conservative columnist were prohibited from further publication because he had suggested that many people were identifying as indigenous solely because it had become trendy to do so. This is perhaps a crass point to make, but not one that adults cannot reasonably be exposed to.

Though it may be meant well, the censorship of ugly or even disturbing speech is still censorship. Bad ideas do exist and the only harm is in hiding them.

Adam Rossi, youth advisory board, July-December 2017

Adam Rossi – Vancouver, Canada

Rossi is a Canadian student pursuing an MA in International Relations. He recently spent a year teaching English in Barcelona, Spain

Seven years after Catalonia’s government outlawed bullfighting in the autonomous region, its officials now find themselves back in the ring. They’ve been thrown in with a great bull, the Spanish government, which has been trying to skewer any Catalan public figure expressing pro-independence views as if they were matadors clad in red.

They have already suspended, fined, and barred from office the former Catalan prime minister, some of his cabinet members, and city councillors for organising a mock referendum back in 2014 and for continually speaking publicly about their belief in the need for real independence. Joan Coma, a leftist city councillor of the Catalan CUP party, now faces an eight-year prison sentence with his passport confiscated for saying, “To make an omelet, you must break some eggs,” in a discussion on independence. Spanish authorities claim that this was a call for political violence. Meanwhile, Spanish President Manuel Rajoy has even threatened to use force to stop the referendum. Not allowing the vote to happen would be undemocratic, essentially ignoring the voice of the people. In addition, these targeted shots at individual citizens such as Joan Coma only serve to drag Spain back to a dark past of civil oppression. They are even using the Francoist penal code to charge Coma. However, these acts only seem to be fuelling the hearts of Catalans, as street demonstrations and “si” vote flags begin to fly proudly outside people’s homes. The current Catalan president, Carles Puigdemont, says the vote will happen regardless, and that the Catalan government will be prepared for immediate separation if the result is a “yes.”

Huw Roberts, youth advisory board, July-December 2017

Huw Roberts – Hampshire, UK

Roberts graduated from Durham University in June 2017 with a BA in Politics. He has been granted a scholarship to study Public Administration at Shanghai Jiao Tong University

In May 2016 major social media firms, including Facebook and Twitter, signed up to a voluntary code of conduct aimed at combating illegal hate speech. This agreement, in partnership with the European Commission, required the signees to remove hate speech posted on their platform within a twenty-four hour period. Since this deal, the pressure placed on these companies to remove hate speech has been increasing, with proposals forwarded by European Union member states for binding legislation and punitive fines. Undoubtedly, the scope for the facilitation and proliferation of hate speech on these platforms requires a response, however, the current demands being placed on social media firms are fostering policies which often lack refinement and curtail legitimate free speech.

Leaked documents from earlier this year revealing Facebook’s hate speech policies typify the problems censorious practices can raise for free expression. The leading headline from these documents was that white men (as a group) were considered a protected category, yet, black children were not. As such, under Facebook guidelines attacks directed against white men were required to be removed, whilst those targeted at black children were permissible. This policy would not only seem discriminatory towards those most vulnerable within society, but has also proven detrimental to discourse. For example, campaigners from social justice groups such as Black Lives Matter have found their accounts blocked due to criticising structural privileges held by white men. Without an overhaul of the current guidelines in place and a more nuanced approach to censoring hate speech, those most marginalised within society risk having a vital outlet for raising debate and challenging inequalities shut down.

Madara Melnika, youth advisory board, July-December 2017

Madara Melnika – Riga, Latvia

Madara is a law student at University of Latvia. She has also studied in Salzburg and Berlin

At the beginning of July 2017 one of the most popular sports commentators in Latvia, Armands Puče, was dismissed from covering the Latvian Kontinental Hockey League club Dinamo Riga’s games. Although he was dismissed by the private media enterprise MTG TV Latvia, this case is noteworthy as the journalist claims that the decision on his dismissal was taken after the company received an ultimatum from the KHL bureau in Moscow, threatening to end the KHL’s broadcasting agreement with MTG TV unless Puče was removed.

His colleagues hinted that “just like in Soviet times”, all of the articles written by Puče in his parallel work as a journalist, in which he criticised the political ideology of the KHL and its impact on Dinamo Riga, had been translated into Russian and sent to the KHL main bureau in Moscow. It is important to stress that the mentioned articles were not connected to his hockey broadcasts.

After some time, the media enterprise claimed that its cooperation with Puče was ended due to plans for a new show concept, which would include also changing the anchor of the broadcast. Thus Puče, who had led the Hockey studio ever since the first season of the renewed hockey club Dinamo Riga, had to be let go.

Of course, the commentator is connected to his media employer and represents it. However, can the fate and work opportunities of a sports commentator absolutely depend on his ideology and activities done outside work – and will the teams suddenly play better, if their games are covered by loyal commentators?

Daniel Penev, youth advisory board, July-December 2017

Daniel Penev – Kyustendil, Bulgaria

Penev is a Bulgarian freelance journalist and a member of the Association of European Journalists

Valentin Todorov is a journalist from Novi Iskar, a town in western Bulgaria, who owns the local news website www.noviiskar.bg. He registered the website under this name in 2010. In June, Todorov learned that Daniela Raycheva, the mayor of the district since 2011, had challenged his right to use this domain. According to the general terms set out by Register BG Ltd., which administrates web domains in Bulgaria, the names of municipalities and regions are reserved for domains registered by the respective administrations. However, when the name is already in use, the parties wanting to use it must either choose another name or wait until it becomes vacant. Here comes the gist of the struggle: when he registered his website, Todorov secured a declaration in which Valentin Kotov, then mayor of Novi Iskar, explicitly states that he will not claim the name while it is active.

“There arises the question as to whether the public administration may, whenever it wishes, make claims in relation to something it has given away and which a citizen owns and has invested in for years,” the Association of European Journalists – Bulgaria wrote in July. “Trust is a media outlet’s greatest capital and it is inseparably connected to its name.”

Todorov suspects that the district mayor resorted to such actions because of the website’s more critical reporting on the various problems in the district. Notably, the mayor only decided to challenge his use of the domain six years after she took office. The administration also already has its own website, www.novi-iskar.bg. Todorov is optimistic about the outcome of the dispute, due by the end August, but if the Register BG commission rules in favour of the mayor, this will set worrying a precedent for all media outlets in Bulgaria.

Sophie Baggott, youth advisory board, July-December 2017

Sophie Baggott – London, UK

Baggott is a journalist focused on promoting human rights

Another resounding voice has blasted proposed changes to the regime protecting official information in the UK, which would deem anyone who communicates information seen ‘to prejudice the United Kingdom’s safety or interests’ or anyone who ‘obtains or gathers’ such information as having committed an offence, potentially resulting in a jail sentence of up to 14 years. To what extent will our government listen to the outcry?

“The proposals threatened would be ‘both retrograde and repressive’”, said the News Media Association (NMA) in a 20-page document released at the end of July. The NMA, which speaks for national and regional UK news media, has highlighted the industry’s concerns about consultative proposals for changes to the Official Secrets Acts and the Data Protection Act, as well as to other unauthorised disclosure offences.

The proposed reforms would lead to ‘damaging and dangerous inroads into press freedom by making whistle-blowers, journalists and media organisations prime targets for state surveillance and criminal prosecution’, the NMA warned. The association said the changes would ‘extend and then entrench official secrecy’, adding: ‘It would be conducive to official cover up. It would deter, prevent and punish investigation and disclosure of wrongdoing and matters of legitimate public interest’.

Investigative journalism could endure a ‘chilling effect’, said the NMA, from how the changes would make it easier for the government to prosecute anyone involved in obtaining, gathering and disclosing information, even if no damage were caused, and irrespective of the public interest. The proposed reforms might also precipitate a more widespread use of state surveillance powers against the media under the guise of suspected media involvement in offences. This would pose a threat to confidential sources and whistle-blowers, the NMA noted.

Is the government going to reconsider or restrict? Either way, the media industry will certainly have to remain on high alert for the foreseeable future.

Dan Bateyko, youth advisory board, July-December 2017

Dan Bateyko – Sarasota, Florida

Bateyko is an internet rights researcher from Sarasota, Florida. He is currently travelling on a Watson Fellowship, a one-year purposeful grant for global independent study

U.S. Twitter users blocked by their twit president might have a remedy. On July 11, the Knight First Amendment Institute filed a lawsuit arguing that US President Donald Trump violated the First Amendment rights of dissenting citizens when he blocked them from reading his tweets and contributing their own. Speaking to Index, Katie Fallow, senior staff attorney at Knight Institute, distilled the issue:

“The president may be using social media in a new way, but the First Amendment principles at stake are longstanding. When the government sets up a public forum, whether on Twitter in a town hall, it can’t exclude people just because it doesn’t like what they have to say.”

But whether Trump’s Twitter account can be considered a public forum is a point of contention. As the Knight Institute argues, Trump’s account has all the hallmarks of a public forum; the account tweets news on policy and provides a platform for public debate. However, in a recent statement, the justice department rejoined that Trump’s editorial control over who to follow and block on his private account is not a constitutional issue.

I chose to highlight this case in my first blog post as a member of Index’s youth advisory board because social media is an incredible tool for giving citizens a voice, granting them a platform to exchange views and petition their public officials. But where and how free speech rights extend online is still far from clear—as Lyrissa Lidksy, dean of Missouri’ School of Law, writes, determining whether comment removal on government-sponsored pages is constitutional “requires close examination of the U.S. Supreme Court’s public forum and government speech doctrines, both of which are lacking in coherence – to put it mildly.” With clarity, public officials once reticent to tackle the thorny issue of public accounts could feel comfortable with more online civic engagement. And by establishing further precedent, the Knight Institute’s defense of Twitter users will hopefully protect people’s hard-fought rights to free expression online.

Isabela Vrba Neves youth advisory board, July-December 2017

Isabela Vrba Neves – Stockholm, Sweden

Vrba Neves is a journalist and writer based in Sweden, and a graduate from Kingston University London

Sweden is known for having a good track record when it comes to freedom of expression, and is regarded as being an example in democracy and equality. However, the Nordic country has recently been faced by a wave of threats by far-right groups attacking journalists and media organisations. In February 2017 journalist Evelyn Schreiber received hundreds of death threats and threats of sexual violence after questioning a Facebook post by Peter Springare, a police officer who heavily criticised immigrants for violent crimes.

Springare received support by far-right groups who went after Schreiber with messages and phone calls. In a radio interview Schreiber explained how she believed the threats were “organised” as she would receive a large amount of messages every time a far-right group shared her article on Facebook.

She also described how at first the groups mostly criticised her article, but then progressed to personal vulgar and sexist attacks towards her. The newspaper, Nerikes Allehanda, which published her article, reported the threats to the police.

An issue that Schreiber brings up with these kinds of incidents is that journalists may self-censor for their own safety, which in turn can threaten freedom of expression. To combat this, the Swedish government announced in July 2017 an action plan which aims to strengthen the preventative work towards hate and threats against journalists, artists and elected representatives.

The Swedish Victim Support and the Swedish Crime Victim Compensation and Support Authority have been commissioned to develop material that will provide knowledge and support to those who have been under threat for participating in public conversations, in order to strengthen free speech and freedom of expression.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content”][vc_column][three_column_post title=”More from the youth advisory board” category_id=”6514″][/vc_column][/vc_row]