12 Jun 2012 | China

Feng Zhenghu. Image by Lara Farrar.

This piece originally appeared on the Huffington Post and is cross-posted with the author’s permission

Just down the street from Fudan University, one of the top colleges in China, and across from a massive shopping complex that has a Wal Mart, a couple of Starbucks and KFCs, H&M, Sephora and Zara, among other Western brands, lives Feng Zhenghu who for 24 hours a day, 7 days a week is barred from leaving his home.

In 2009, Feng garnered international media attention when he lived in Tokyo’s Narita Airport for several months after the Chinese government repeatedly stopped him from entering the country. He eventually was allowed to return to his apartment in Shanghai in 2010 and since then has faced random detentions in his home, which is also regularly searched for contraband by police.

“I don’t know if there is any surveillance in my house, and I don’t care,” said Feng who is reachable via mobile in his apartment, which is just a couple of buildings away from mine in a complex that has a fish pond, palm trees and a playground. “My phone is recorded, my computer has been taken. They can come to my house anytime without notice as they please. I have no privacy at all, and it is all public to them.”

Feng has become an enemy of the state for the work that he does to educate petitioners about their rights under Chinese law.

China has hundreds of thousands, perhaps even millions, of petitioners, or people who file grievances with the government against local officials for abuses ranging from corruption to forced land acquisition. They are usually poor, which means they cannot hire lawyers to help them solve their cases, which are also rarely ever heard in local courts. This means that most petitioners make dozens of trips to Shanghai over the course of many years to try to find someone powerful in the central government to help them find justice. Most never find any help at all.

The dissident has made it his mission to push local courts to not dismiss cases from petitioners as well as help petitioners write court documents or other papers outlining their particular complaints. And for this, he has lost his freedom.

In the beginning, when I moved into my apartment back in 2010, the security apparatus was barely noticeable. There were always some random men who looked like the type of men who might be found late at night in a stale diner in a casino in Atlantic City. Thuggish. Gold chains. Greasy hair. One had a broken arm.

They would sit at the gate and smoke. After a while, they started talking to me. Offering me cigarettes. I would stand around and chat about America. It was a good way to practice Chinese. I thought they were part of the complex’s management team. Once I asked what they did, and they replied that just had some sort of random business to do in the neighborhood. I thought nothing of it. Nor, it seemed, did anyone else who lived around me.

I discovered who the men were and why they were there only a few months ago when a Chinese friend of mine who worked for a foreign news agency came to interview Feng. The police arrived to stop him and the foreign reporter from entering Feng’s building so they came to my apartment for tea. Since then, I have been in touch with Feng via phone to ask him some questions surrounding some stories I have been working on about black jails in China and to ask him about what it is like to be in prison in his home.

“If I escape, those guards, the local public security bureau chief, the district governor, all of them will lose their jobs,” he said. “I have been with them for two years, and I understand them. It is also hard for them, so I don’t want to try to run away. Summer is coming, and I worry for them. The sun and mosquitoes are coming, and they have to stay outside. It is a pretty hard life for them as it is for me.”

Since the blind Chinese dissident Chen Guangcheng dramatically escaped from house arrest in a rural village in northern Shandong Province at the end of April, the layers of security surrounding my apartment complex have multiplied. The guards are still at the gate. But now there are more who hang around all day near the entryway to Feng’s building. There are new security cameras by the entrance. This week, new ultra bright lights were installed on the grounds.

And now in front of Feng’s building is a police car round-the-clock. I walk by it everyday. On my way to go buy coffee or cigarettes or a newspaper, I peer inside the tinted windows where I see bored officers watching something on their mobile phones. The car is always on. Sometimes there are people sitting in the backseat. Sometimes there are not. Sometimes everyone inside is asleep. Sometimes they sit outside a small tea shop and watch me pass. One night, one even said hello.

Back in April, before the police car arrived out front, my news assistant and I called Feng early one morning. We said we would come to see him from the street. He walked to his window and briefly peered outside. We snapped a photo. He dropped us a package with a note that said he is allowed to walk outside in the afternoon for half an hour for fresh air, and that maybe we could see him then.

Via phone, Feng told us that, unable to take the constant surveillance, his wife has moved to Germany.

“My life has become worse after her departure,” Feng said. “I cannot even go out to buy food. I rely on visitors to bring me food, and I cook a lot at once, and just eat the leftovers for meals.”

Georgie is a neighbor who visits Feng when he is let out of his apartment in the afternoons. Over the years, Georgie has developed a rapport with the guards, which now number at nearly 20 or so. He says they are migrant workers from provinces around Shanghai and make a couple thousand yuan per month to monitor the dissident. When Feng is let out, he talks to the guards about current events or cooking.

They talk about “how to stay healthy or what kind of television they are watching or how to cook fish. That was yesterday’s topic,” said Georgie who requested his full name not be disclosed out of fear that he would no longer be able to visit Feng anymore.

“Some of them, they have a good relationship [with Feng],” he said. “The guards just consider this as any other job.”

The degree to which my neighbors are aware that their neighbor is a dissident who is in prison in his home is unclear. There are daily rhythms of life here. Cars come and go. Children play soccer outside. Elderly men walk their dogs. Women sit around the fish pond and chat in the evenings. Every time I enter the gate, I look left towards Feng’s apartment and wonder what he is doing, whether he will ever get out and whether, for me, if it would have been better to never know that he was there at all.

“They are very worried right now that in Shandong a blind person could escape such heavy security,” Feng said. “They afraid that I might run away too, and then they will lose their jobs. So their days are not easy right now.”

Lara Farrar is a China-based correspondent, working for CNN International, the Wall Street Journal, Women’s Wear Daily, and the International Herald Tribune among other publications

4 May 2012 | Asia and Pacific, News and features

Even before the internet, dissidents in exile were able to create networks that provided a lifeline to those back home, writes Index editor Jo Glanville

Even before the internet, dissidents in exile were able to create networks that provided a lifeline to those back home, writes Index editor Jo Glanville

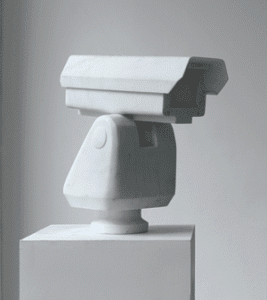

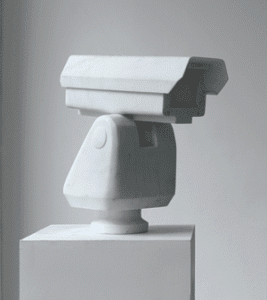

This piece originally appeared on Comment is Free

The desperate plight of Chen Guangcheng is a graphic illustration of how China treats its dissidents. Harassed and intimidated, Chen has spent the past seven years between prison and house arrest since he exposed the government’s forced abortion policy in 2005 (he was awarded the Index freedom of expression award for whistleblowing in 2007). House arrest is a common tactic in China for containing and controlling whistleblowers and activists. In Chen’s case, since his release from prison in 2010, it has meant a life of social isolation and fear. Other current well-known victims include Tibetan poet Tsering Woeser and Ai Weiwei, who famously attempted to turn China’s tactics on their head by installing his own in-house surveillance.

The week’s dramatic events echo the story of celebrated dissident Fang Lizhi, who died last month; Fang also took refuge in the US embassy following the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989 and stayed for more than a year until China allowed him to leave. Fang was one of the most important influences on the Tiananmen generation of young activists and the authorities considered him “the biggest black hand behind the 4 June riots”. In exile in the US for the rest of his life, as well as pursuing his academic career as an astrophysicist, he remained active in speaking out for human rights in China along with other exiles of 1989, including Wang Dan.

The experience of exile for dissidents, despite the continuing possibility for influence, can bring another kind of isolation. “Homelessness, loneliness and despair have almost driven me to self-destruction,” wrote the poet Liu Hongbin on the 20th anniversary of Tiananmen Square. It is only through memory, he has written movingly, that he has made the journey home. Writer Ma Jian, who has written the definitive novel of the Tiananmen generation, Beijing Coma, while in exile, was still able to visit China regularly until last year – a measure of how far the situation has deteriorated. Chen’s desire for “a rest”, as he told Congress, is likely to be more than a short stay.

However, there are networks that can only be built from exile and that have always been a lifeline for dissidents back home, long before Twitter, SMS and Facebook revolutionised the possibilities of making revolution. Under editor George Theiner, a Czech dissident in exile in London, Index on Censorship magazine published the leading lights of Czechoslovakia’s pro-democracy movement in the 80s, most notably Václav Havel, as well as publishing and distributing Polish and Czech samizdat – a vital outlet for opposition activists. When Index’s founding editor Michael Scammell started publishing the most famous dissident of them all, Alexander Solzhenitsyn, the great man panicked: when he heard that his work was appearing so widely in English, he thought it was the KGB who was circulating his writing as part of a political provocation. But it was the first worldwide publication of much of his work in translation and an immensely important part of circulating the plight of dissidents in the Soviet Union.

Forty years on, Belarusian activists in exile have played a vital role in galvanising opposition to Alexander Lukashenko’s regime. Since the elections in 2010, following the mass arrests and imprisonment of the opposition, some of the leading lights of the pro-democracy movement have settled in London and Warsaw where they have helped to shape a successful European campaign alongside human rights groups. Natalia Kaladia, artistic director of the acclaimed Belarus Free Theatre, had to flee Belarus following her arrest and the intimidation of her family. In a campaign with Index, her new organisation Free Belarus Now, which she runs with Irina Bogdanova, sister of former political prisoner Andrei Sannikov, has helped to persuade Deutsche Bank and BNP Paribas to stop doing business with Lukashenko’s regime.

While none would choose exile, Chen is reported as telling the US ambassador that “he wanted to be part of the struggle to improve human rights within China”, thanks to the internet it is now perhaps more possible than it ever was in the days of the carbon copies of samizdat to continue to exert an influence back home.

Jo Glanville is editor of Index on Censorship magazine

26 Apr 2012 | Asia and Pacific

The artist Ai Weiwei’s outspoken views are gaining currency. Simon Kirby reflects on a change of mood in China as people lose faith in the Party

In June 2011, Ai Weiwei was released from detention to a form of home surveillance. He is confined to the city of Beijing and must inform the authorities of his movements. He may not make public statements nor comment on his detention and the terms of his release (a condition he has already breached); further investigations are pending and a prosecution may be pursued within a year. It is still far from clear what the implications are for Ai as a private individual, let alone for his capacity to continue to work as an artist. Just as he was never formally arrested neither has he been fully freed.

This shabby story takes place against a backdrop of heightened political sensitivity in China as the country braces itself for transition to a new, as yet unannounced, group of top leaders. This is scheduled to take place next year in the Great Hall of the People during the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party. The Congress will certainly be a rigid spectacle of national purpose and will make numbing television viewing. Not least because it will be impossible not to speculate on the nature of the Byzantine succession struggle which is currently taking place behind firmly locked doors.

This shabby story takes place against a backdrop of heightened political sensitivity in China as the country braces itself for transition to a new, as yet unannounced, group of top leaders. This is scheduled to take place next year in the Great Hall of the People during the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party. The Congress will certainly be a rigid spectacle of national purpose and will make numbing television viewing. Not least because it will be impossible not to speculate on the nature of the Byzantine succession struggle which is currently taking place behind firmly locked doors.

The detention of Ai Weiwei was based on intimidation rather than legal process — a pattern that is well established in China. In effect, he was kidnapped by the state and never informed which organ of the machinery was holding him, nor was he charged with a specific crime. Rather, his indictment was based on “confessions”. Even his release was justified on the spurious grounds of cooperative behaviour, willingness to make amends and poor physical health. As the threat of re-opening the case against him still looms, he is now being blackmailed into falling into line.

A few weeks after Ai Weiwei was released I had lunch with him. He talked frankly about the contradictions of his detention and the absurdity of his current position. He clearly intends to continue working and his remarkable personal charisma is undimmed. Yet he is, in my view, a person who is also deeply disturbed by what is happening to him.

Artists and the “Tiananmen contract”

Throughout the 90s, Chinese state-controlled capitalism ushered in a remarkable economic boom from which the fledgling contemporary art scene benefited. Artists, as potentially problematic figures, were heavily co-opted with a variety of sticks and carrots — there were rich rewards to be had and the freedom to continue making, exhibiting and travelling was granted to artists in exchange for creating non-critical work. In many cases, artists were understandably tempted to comply. Ever since the fearful events of the Tiananmen massacre on 4 June 1989, there has been an enforced accommodation between the government and society. I dubbed this the “Tiananmen contract” in an article for Index on Censorship that was published in 2008, ahead of the Chinese Olympics. The deal is that the Communist Party would steer the people towards individual prosperity and the country to greatness, through ensuring stability. In return, the primacy of the Party could never be questioned. Three years ago, the contract was widely supported — the level of basic freedom was greater than it had been in 20 years and living standards were rising. There was also pride at China’s leading role on the world stage. Today, I believe this consensus is much more fragile.

The daily reality for Chinese citizens is that living costs are rising fast and incomes are not keeping up. Working conditions for white collar workers can be demoralising, while those for migrant manual workers, who continue to have even basic rights denied them, are often shockingly exploitative. Commuting in the new, high-rise cities can be exhausting and alienating. People are deeply sceptical about the capacity of the state to protect them from (often deliberately) contaminated food and a toxic living environment, criminal scams, corruption in the medical profession and corporate exploitation of consumers. The Party is widely understood to be at the centre of many of these scandals and is often seen to be protecting wrongdoers. Most flagrantly, the new super-rich live effectively beyond the reach of the law, while ordinary people can in no way count on basic social justice for themselves and their families.

The daily reality for Chinese citizens is that living costs are rising fast and incomes are not keeping up. Working conditions for white collar workers can be demoralising, while those for migrant manual workers, who continue to have even basic rights denied them, are often shockingly exploitative. Commuting in the new, high-rise cities can be exhausting and alienating. People are deeply sceptical about the capacity of the state to protect them from (often deliberately) contaminated food and a toxic living environment, criminal scams, corruption in the medical profession and corporate exploitation of consumers. The Party is widely understood to be at the centre of many of these scandals and is often seen to be protecting wrongdoers. Most flagrantly, the new super-rich live effectively beyond the reach of the law, while ordinary people can in no way count on basic social justice for themselves and their families.

There are attempts to address these problems through draconian anticorruption campaigns which make examples of officials accused of vice and graft. There are also strenuous efforts to reform social and fiscal legislation and to professionalise the legal system. This year’s 90th anniversary celebrations of the founding of the Chinese Communist Party saw an outpouring of congratulatory media stories featuring joyful ethnic minorities, good comrades and citizens and glorious historical deeds. Meanwhile Tiananmen Square, which is the heart of the great people’s revolution, was firmly sealed and off limits.

In March, I had dinner in a noisy Korean barbecue restaurant in Beijing with a favourite Chinese artist. Only 32 years old, he already enjoys a successful international career, is profoundly patriotic and the holder of an important teaching post. During the evening, my friend passionately expounded an opinion in full earshot of fellow diners and waiting staff that would have made me extremely uncomfortable even five years ago. Namely, that the Chinese Communist Party in 2011 is more fundamentally corrupt than even Chiang Kai-shek’s Kuomintang (KMT or Nationalist Party) of the 40s. The official history, tirelessly propagated in films and TV dramas, is that that the nationalist administration had degenerated into a kind of murderous gangsterism before the 1949 revolution. Yet my artist friend argued that pre-revolutionary society in many ways remained, for all its faults, a pluralistic one: an imperfect democracy. There was at least formal acknowledgment of the independence of the judiciary and channels to seek redress from injustice. The Communist Party of the 21st century, on the other hand, retains its monopoly on power through intimidation and force. It is deeply complicit in land grabs, forced evictions, endemic bribery and corruption. It even facilitates the enrichment of favoured businesses through official contracts and privileged access to resources and markets.

A new trend for speaking out

The legal system today, my friend told me, is explicitly in place in order to serve the interests of the Party above anything else. Citizens who attempt to petition the government to redress flagrant social wrongs can expect to be met at best with official obstruction. In many documented cases they will encounter thuggish intimidation and violence. This viewpoint is not unusual. In a way that is entirely characteristic of China, I then went on to hear the same, previously unimaginable, opinion expressed by three other, unrelated people within the course of as many weeks. If during the course of conversation with people in China, one digs just a little, it’s possible to encounter a profound and worrying cynicism in the integrity of the Chinese state.

It seems that suddenly these views are being expressed loudly and in public. Ai Weiwei, on the other hand, has been consistently and persistently making his views known. His father, Ai Qing, was one of China’s most eminent poets, but was a political prisoner for 16 years in the western desert region of Xinjiang. This is where Ai Weiwei spent his entire childhood and early adolescence. When Ai Weiwei returned to China in 1993 after ten years in the United States, his rehabilitated father advised him on his responsibility as a Chinese citizen to speak out, reportedly saying, “You are at home here, there’s no need to be polite.”

It seems that suddenly these views are being expressed loudly and in public. Ai Weiwei, on the other hand, has been consistently and persistently making his views known. His father, Ai Qing, was one of China’s most eminent poets, but was a political prisoner for 16 years in the western desert region of Xinjiang. This is where Ai Weiwei spent his entire childhood and early adolescence. When Ai Weiwei returned to China in 1993 after ten years in the United States, his rehabilitated father advised him on his responsibility as a Chinese citizen to speak out, reportedly saying, “You are at home here, there’s no need to be polite.”

An intriguingly enigmatic artist, Ai Weiwei’s public personality is also complex and elusive. The true Ai Weiwei may well be a nuanced combination of the many faults of which his detractors accuse him. However, it has also now become clear, even to his harshest critics, that this artist has courageously maintained a highly principled position for which he is now paying a heavy price. It is my observation that many others are beginning to come round to his point of view.

This article appears in the “Art Issue” of Index on Censorship. Click on here for subscription options and more.

Simon Kirby is the director of Chambers Fine Art in Beijing

This issue is nominated for an Amnesty Award

26 Mar 2012 | Leveson Inquiry

A senior police officer has claimed that tabloid journalists picked up a suspect in the serial murder case of the “Suffolk Strangler” to interview away from police surveillance.

Supporting the claim made last week by retired criminal investigator Dave Harrison, Chief Constable Simon Ash from Suffolk Constabulary told the Leveson inquiry he had obtained information to support the claim that a surveillance team was employed to “pick up and interview” the first suspect in the inquiry into the Ipswich murder inquiry of 2006. Despite supporting information in Harrison’s written statement, Ash did not name name the Sunday Mirror.

Ash was not working at the force in 2006, when the “Suffolk strangler” case received intense press coverage, but the police officer told the Leveson Inquiry: “On the assertion that a newspaper picked up a suspect and took them to a hotel and interviewed them while under police surveillance, I have been able to find information to support that.”

In relation to further claims from Harrison that News of the World had spied on the police and jeopardised the case, Ash told the court that he had not been able to find any information to support the assertion that the News of the World were deploying surveillance teams.

Ash explained to the court that relations were “very good” between police and local press. He said that there is a “healthy” relationship between the two parties, and described meeting editors on an “ad-hoc basis – to resolve whatever the current issues are. We work together for the good of our community.”

The Chief Constable also explained that staff in Suffolk Constabulary are encouraged to pro-actively highlight the good work of staff. He added: “Bad news almost writes itself, we have to work hard to promote the good work officers and staff do day in and day out”

When asked by Robert Jay, QC, if he felt that the corporate communications department of the police force only dealt press a “party line”, Ash denied this: “I think we’re all of the view we take the rough with the smooth, but my overall objective is to create confidence in the police. As we all know, things don’t always go to plan, and sometimes we have to give an apology, explain what happened, and I think that is equally as important as promoting the good work we do.”

Also appearing before the court, Terry Hunt, the editor of East Anglian Daily Times stressed the importance of good relationships between the press and local police forces. Hunt described the key relationship between the two in relation to the Ipswich murder case, after the national press descended on the town, and suggested that the local media were more balanced than the national press.

The editor said: “We were very aware of what the national press were reporting at the time. It was part of our responsibility to put this into some kind of context because there was a great deal of concern about what was going on in a very fast moving, and frankly horrifying story.”

But despite describing the relationship between the two parties as “generally supportive,” Hunt labelled the speed of response from the police as an “area of frustration”.

Hunt told the court of an incident in which three potentially dangerous men escaped from a secure mental health unit. The editor explained that at the time, he had hoped and expected that Suffolk Police would have responded in a more timely fashion.

He said: “These three individuals escaped in the early hours of Sunday morning and were at large in Suffolk and were potentially dangerous. I would have hoped and expected that Suffolk police would have put some information on that into the public domain, so that when Suffolk awoke in the morning, members of the public were forewarned. I felt it very unfortunate that that information did not reach us until lunchtime that Sunday.”

Hunt described a “heightened sensitivity” with regard to the relationship between press and police, explaining that there have always been some police officers who have been reluctant to share “legitimate” information. He added that if the recommendation of recording all contact between the press and the police “if enshrined will be a step backwards for a number of people who are concerned that by talking to the press they might get themselves in trouble.”

Anne Campbell, the head of corporate communications for Norfolk and Suffolk Police, and chair of the Association of Police Communicators (APComm) also appeared before the court, and agreed that local media offer a more rounded view of news stories.

Campbell said: “The local and regional media are constantly covering the issues and the stories of the constabulary, so you build up a daily relationship. They’re more keen to build up a rounded view.”

She added: “We expect journalist will be fair, balanced and accurate. That’s what we work with the media to see reflected, even if the stories are not so good news.”

When asked if corporate communications is a way of controlling what is distributed to the press, Campbell disagreed, and said that communications is “a news editing role, not a control role”.

Campbell stressed that any briefing of police officers was also not to put a slant what was released to the press and public, but to ensure that the police officer has “in his or her armoury the most up-to date information”.

She added: “We’re managing a situation of a lot of demand from the media. We either let officers without any assistance deal with that, potentially in an unhelpful way which will potentially take up a lot of their time. Our role is actually to free up the officers so they can spend the time on what the public want them to do primarily.”

Campbell also suggested “overarching guidelines” would be beneficial for police forces, enabling them all to “sing from the same hymn sheet”

Relating to her second statement to the inquiry, described by Lord Leveson as the statement in which she was wearing her APcomm hat, Campbell told the court that she was not too concerned about leaks to the press, as long as the police were given the opportunity to give a balanced picture.

Anne Pickles, associate editor of Carlisle News and Star, and Nick Griffiths a reporter for the paper agreed that the relationship between the press and public was key.

Pickles told the court that her relationships with the police have been built on mutual trust and respect and that the two parties both serve a common purpose and community. She added that as they lived with those they were reporting on, their role and coverage within the region was crucial.

But the editor explained that national media worked in an entirely different way. She said: “It’s always been my experience that national media are able to sweep in and sweep out into some sort of black hole of anonymity.”

Griffiths added that local press an police worked to the same ends. “We’re trying to get certain information across to the public. There’s a trust there, and relationships are generally working quite well.”

During the high-profile news case of the Derrick Bird shootings in Cumbria, Pickles told the court that journalists from the Crime Reporters Association sought preferential treatment and off the record information.

She added: “We didn’t want to spend a lot of time harassing the victims families looking for big headlines. We didn’t want to cause them further distress. We worked very closely with the police liaison team, who were very helpful in gaining photographs, tributes, anything else we might need. For all it was a dreadful incident, it was, perversely I know, an extremely successful police/local media operation.

Both parties from the Carlisle News and Star felt it was unnecessary to “drive a wedge between local press and local police.”

Pickles told the court “The stain from what has happened to trigger this inquiry tends to spread across all sections of the media. It’s quite clear we’re in a bad place in some sections of the media, but I still think a lot of the media has to blame itself for that, and take responsibility for it.”

Deputy Commissioner Craig Mackey, former Chief Constable of Cumbria Constabulary and Gillian Shearer, Head of Marketing and Communications also gave evidence.

Shearer described the massive pressure faced by the constabulary’s press office in the wake of the Derrick Bird shootings. She explained that an immense number of calls to the press office meant that they had to hire more staff. Shearer told the court that calls to the press office went from 30-50 a day to 300-500 a day.

She added: “In Cumbria the local media has a really unique role. They do a lot of reporting around crime and the people in Cumbria read and believe the newspapers.”

The pair described to the court instances of harassment by national media towards the families of the victims. Shearer explained that the families were “completely and utterly overwhelmed” by the press coverage, and told the court that some contact from the press was made before the police had informed the families of victims.

Shearer said: “We were in contact with the PCC over grieving families feeling harassed. They asked us to tell people to call them.” She added that print and TV media continued to doorstep the bereaved after a request to pull back.

Mackey added that the families felt anger and dismay at the way they were treated, and described “upsetting behaviour”, as rumours spread that money was available for certain photographs.

Colin Adwent, crime reporter for the East Anglia Daily Times told the court it was important to “be able to talk to police officers of all ranks without fear of favour.”

Adwent reiterated the belief that press and police should have a healthy, professional relationship. “If officers are responsible enough to deal with life and death, they’re responsible to know what they can talk to the press about.”