22 Jan 2026 | Europe and Central Asia, Features, Russia, Volume 54.04 Winter 2025

This article first appeared in the Winter 2025 issue of Index on Censorship, Gen Z is revolting: Why the world’s youth will not be silenced, published on 18 December 2025.

It’s something of a surprise to learn that the rap music genre in Russia dates as far back as the Soviet era – and that then, it came about thanks to a woman, Olga Opryatnaya. Second director of the Moscow Rock Club, sometime in the mid-1980s she heard a performance by the group Chas Pik. Struck by their innovative funk-rock fusion overlaid with an MC’s flow, Opryatnaya invited them to record an album. And thus, Russian rap was born.

Today, Russian rap music made by women coalesces around Zhenski rap, a sub-genre that emerged in the mid-1990s. Starting with Lika Rap, the 1994 album by Lika Pavlova (aka Lika Star), women have “represented” in what remains in Russia – as elsewhere – a male-dominated genre.

But this has not been a smooth ride. And as the curious case of Instasamka, the first female rapper to be subjected to state censorship shows, double standards abound – with women being targeted, unlike their male counterparts, with ambiguous charges of “moral inappropriateness”.

The censorship of women musicians in Russia is not, it should be said, a recent phenomenon. Pussy Riot, the feminist political collective, have been persecuted for more than ten years, with five of their exiled members sentenced in absentia in September 2025 to long jail sentences for speaking out against the war in Ukraine. But their cause went largely unnoticed within Russia’s rap community.

Now the war between Instasamka and the authorities, beginning in late 2021, has added cultural censorship to the well-established category of suppressing political speech.

A vlogger and social media personality before becoming a musician, Instasamka’s older Instagram posts give a good sense of her defining aesthetic – accentuated physical features interspersed with tattoos, tropes often featured by her counterparts in the USA. Rubbing against the conservative – anti-foreign – values that have been in ascendency in Russia in recent years, it was no surprise that she would, in due course, attract the wrong sort of attention.

The offensive against Instasamka (real name Darya Zoteeva) was initially led by state organisations and civic organisations on 24 November 2021. The Rospotrebnadzor, the Federal Service for the Oversight of Consumer Protection and Welfare, cancelled her concert after complaints from members of the Surgut city Duma in Khanty-Mansia. The day after, the media watchdog Roskomnadzor cancelled her concert in Sverdlovsk due to similar complaints from local officials. The censorship campaign against her picked up, though, after being taken up by conservative parental groups like Fathers of Russia. A concerted campaign accusing her of promoting debauchery and prostitution among children starting in December 2022 led, ultimately, to the cancellation of her February 2023 tour.

Wilting under the pressure, Instasamka temporarily relocated to the United Arab Emirates, albeit in a precarious financial position – her bank account had been frozen by the Ministry of Internal Affairs due to an investigation on charges of tax evasion and money laundering.

The fraught situation that Instasamka found herself in only began to unwind in the late spring of 2023, following a meeting between her and Katerina Mizulina, head of the Safe Internet League. At the meeting, Instasamka and Hoffmannita (a fellow female rapper similarly targeted by conservative pressure groups) publicly apologised to concerned parents, and undertook to reform their public personas.

Her travails were far from over, however. Instasamka’s unapologetic pop (read: commercial) sensibilities had always set her out on a limb. In a music form that has traditionally (if not always consistently) prided itself on social awareness and political literacy, Instasamka’s peers themselves labelled her with one damning word: inauthenticity. By late 2023, the perception of Instasamka in Russia’s rap community was one of vocal disgust rather than silent tolerance, “I forbade my children from listening to Instasamka,” Levan Gorozia from rap group L’One told Index. “They need to understand what’s good and what’s bad.”

Similarly award-winning, rapper Ira PSP noted: “I haven’t heard of such names. They’re probably pop projects; all the rappers know each other.” Kima, another well-known rapper in the community, explicitly questioned the artistic credentials of her “peer”. Instasamka, she said, “is a successful commercial project. She’s great at copying Western artists. I don’t think of her as a rapper. […] A girl who raps can call herself whatever she wants, but she’s not a rapper if someone writes lyrics for her. I haven’t heard decent female rap lately that has both substance and a decent flow.”

But there is, perhaps, another dimension to Instasamka’s support – or lack of therein – within Russia’s female rap community.

As one member of rap group Osnova Pashasse – one of the oldest all-female rap groups in Russia – pointed out (anonymously but speaking for the group), the issue goes far deeper. “In our country, many still don’t take rap with a female voice seriously,” she said. “Perhaps this is the fault of the female MCs themselves who don’t focus their work on something interesting, with intellectual or spiritual themes, or even some captivating abstraction in their lyrics, but instead constantly emphasise their gender in their lyrics and sometimes try to compete with men.”

Credibility for female rappers, it seems, does not sit easily with commercial kudos. But then again, even commercial success is predicated on staying with the boundaries of social and cultural norms – which, in effect, sometimes operate as a form of artistic censorship.

***

The success of female rappers in Russia is, by and large, contingent upon the approval of a male-dominated culture and male-dominated ideas of quality. The historical antecedents of female rappers working in the genre notwithstanding, fair evaluation of their capabilities is not a given. As branding expert Nikolas Koro noted, a small fan base has a marked limiting impact on the visibility and commercial viability of female rappers. “In financial terms, the number of female rap fans is mere pennies. So, the fate of almost all women rappers in Russia is either to leave the stage … or change the musical format.”

Ira PSP expressed the challenges trenchantly. The issue, she said, is that “we are neither heard nor seen. The girls and I have dedicated our lives to culture, but there is no [financial] return.”

So, where is Zhenski rap heading? The balance that its practitioners must try to strike can be found somewhere between the desire to be seen as “authentic” (legitimate in the eyes of the rap community) and being themselves. They must appeal to both the dominant cultural norms within rap and assert their individuality, as women and as rappers. In the 2000s, this meant balancing skill, sex-appeal, and objectification, which only become more pronounced from the 2010s on. And they, of course, must take into account the very real prospect of censorship – creative or cultural, by peers or by the state.

The Instasamka saga did not end with her apology of 2023. After another scheduled tour was cancelled in 2024, on the grounds of her “provocative appearance”, Instasamka finally threw in the towel, declaring that she would rebrand herself and embrace a more socially acceptable demeanour. This she has played out by re-inventing herself as a champion of child safety – and by showing rather less cleavage on Instagram. In July 2025, she participated in a roundtable discussion on a proposed legislative initiative to limit the access of minors to blogging platforms. Instasamka has shifted her entire public persona behind vocally supporting a “pro-child” agenda – completely distancing herself from her past in the process.

She has also, it seems, changed her views about artistic censorship. In July this year, she openly criticised fellow rappers Dora and Maybe Baby for allegedly “anti-Russian” behaviour. Their transgression, in Instasamka’s opinion? Performing covers of songs from firebrands like the rapper FACE. Real name Ivan Dryomin, FACE was a vocal critic of the Putin regime. Forced out of the country, he was labelled a “foreign agent” by the Russian government in 2022.

18 Jul 2025 | Afghanistan, Africa, Asia and Pacific, Benin, China, Côte d'Ivoire, Europe and Central Asia, Middle East and North Africa, News, Palestine, Russia, United Kingdom

In the age of online information, it can feel harder than ever to stay informed. As we get bombarded with news from all angles, important stories can easily pass us by. To help you cut through the noise, every Friday Index publishes a weekly news roundup of some of the key stories covering censorship and free expression. This week, we look at how UK police are interpreting the proscription of Palestine Action, and the detention and extradition of a Beninese government critic.

An oppressive interpretation: Kent woman threatened with arrest over Palestine flags

On 1 July 2025, UK Home Secretary Yvette Cooper proscribed Palestine Action, a pro-Palestinian activist group founded in 2020, calling it a “dangerous terrorist group”. The move, which sees PA’s name added to this list, was made after two members of the organisation broke into RAF Brize Norton airbase on scooters and defaced two military planes with red paint, the latest in a long line of actions taken by the group to halt proceedings at locations and factories they believe to be aiding Israel’s offensive in Gaza. Proscription means that joining or showing support for Palestine Action is punishable by up to 14 years in prison.

The Home Secretary’s decision has provoked controversy. The move has been described by Amnesty International as “draconian” and a “disturbing legal overreach”. Since the ruling, over 70 protesters have been arrested for displaying signs showing direct support for Palestine Action, and numerous lawyers, UN experts and human rights groups have voiced concerns that the vague wording of the order could be a slippery slope into more general support for the pro-Palestinian cause being punished.

On Monday 14 July, peaceful protester Laura Murton was holding a Palestinian flag as well as signs that read “Free Gaza” and “Israel is committing genocide”, when she was threatened with arrest under the Terrorism Act by Kent police. Despite showing no support for Palestine Action, she was told by police that the phrase “Free Gaza” was “supportive of Palestine Action”; police were recorded by Murton stating that “Mentioning freedom of Gaza, Israel, genocide, all of that all come under proscribed groups, which are terror groups that have been dictated by the government.” She was made to provide her name and address, and was told that if she continued to protest, she would be arrested.

Murton told the Guardian that it was the most “authoritarian, dystopian experience I’ve had in this country”. Labour’s Minister of State for Security Dan Jarvis seemed to condemn the incident, stating “Palestine Action’s proscription does not and must not interfere with people’s legitimate right to express support for Palestinians.”

Defying refugee status: Beninese journalist forcibly detained and extradited

On 10 July, Beninese journalist and government critic Hughes Comlan Sossoukpè was arrested in a hotel room in Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire and swiftly deported back to Benin, in violation of his status as a refugee.

Sossoukpè, who is the publisher and director of online newspaper Olofofo, had been living in exile in Togo since 2019 due to threats received regarding his work criticising the Beninese government and has held refugee status since 2021. He had reportedly been invited to Abidjan by the Ivorian Ministry of Digital Transition and Digitalisation to attend a forum on new technologies – one of Sossoupkè’s lawyers accused Cote d’Ivoire of inviting him for the purpose of his capture.

Another of his lawyers, speaking to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), reported that Sossoupkè recognised two of the five police officers that arrested him as being Beninese officers rather than Ivorian. They allegedly ignored his request to see a judge, confiscated his personal devices and escorted him to a plane back to Benin.

On 14 July, Sossoukpè was brought before the Court for the Repression of Economic Offences and Terrorism (CRIET) in Cotonou, Benin, and charged with “incitement to rebellion, incitement to hatred and violence, harassment by electronic means, and apology of terrorism”. He has been placed in provisional detention in a civil prison, and numerous groups such as CPJ, Frontline Defenders, and the International Federation of Journalists have called for his unconditional release.

The crime of a Google search: Russia ramps up dissent crackdown under guise of “anti-extremism”

Russia’s lower chamber of parliament, the State Duma, passed legislation on 17 July that greatly extends the state’s ability to crack down on dissenters. Starting in September, in addition to criminalising taking part in activities or groups that the Kremlin deems “extremist”, you can be fined just for looking them up online.

Anti-extremism laws in Russia have long been used to crack down on organisations whose views do not align with the state’s; There have been over 100 extremism convictions for participating in the “international LGBT movement”, and lawyers who defended opposition leader Aleksei Navalny were also arrested and imprisoned on extremism charges. But with the new changes passed on Thursday, those who “deliberately search for knowingly extremist materials” will face fines of up to 5000 roubles, or around £47.

Extremist materials are designated by the justice ministry via a running list of over 5000 entries which includes books, websites and artworks. Other materials that could result in a fine include music by Russian feminist band Pussy Riot, articles related to LGBTQ rights, Amnesty International and various other human rights groups, pro-Ukraine art or works..

The ruling has been met with a backlash from politicians and organisations from across Russia’s political spectrum; the editor-in-chief of pro-Kremlin broadcaster Russia Today said she hopes amendments will be made to the legislation, as it would be impossible to investigate extremism if online searches are prohibited, while Deputy State Duma speaker Vladislav Davankov reportedly called the bill an “attack on the basic rights of citizens”.

The Taliban vs journalism: Local Afghan reporter detained

In the most recent case of the Taliban’s crackdown on journalism in Afghanistan, journalist Aziz Watanwal was arrested and taken from his home on 12 July alongside two of his friends in a raid by intelligence forces.

A local journalist of the Nangarhar province of eastern Afghanistan, Watanwal had his professional equipment confiscated. Despite his friends being released in the hours following his arrest, Watanwal is still in custody with no information regarding his whereabouts, and the Taliban reportedly gave no reason for his detention.

Since the Taliban seized power in Afghanistan in August 2021, journalistic freedoms have taken a sharp decline. Afghanistan Journalists Centre have reported that in the first half of 2025, press freedom violations increased by 56% compared to the same period in 2024. In the three years following the Taliban’s return to rule, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) reported that 141 journalists had been arrested for their work, and the country currently sits 175th out of 180 countries on RSF’s Press Freedom Index.

Censorship of an archive: Chinese tech corporation seeks closure of crucial social media archive

Chinese multinational tech conglomerate Tencent has launched legal action against censorship archive organisation GreatFire to take down FreeWeChat, a platform run by GreatFire that aims to archive deleted or blocked posts on prominent Chinese messaging and social media app WeChat.

WeChat is one of the most popular apps for Chinese citizens and diaspora, and posts on the platform critical of the government are frequently subject to censorship. FreeWeChat was created in 2016 in an effort to catalogue posts taken down by Chinese authorities, but it is now under threat from this legal attack by Tencent.

Tencent’s claim is that FreeWeChat’s use of “WeChat” in the domain is a trademark and copyright infringement, submitting a takedown complaint with this reasoning on 12 June. GreatFire rebutted the allegations, stating that they do not “use WeChat’s logo, claim affiliation, or distribute any modified WeChat software”, and claim that Tencent’s intent is to “shut down a watchdog”.

Martin Johnson, lead developer of GreatFire, stated that the organisation have previously dealt with state-sanctioned DDoS attacks, but they have outlined their intent to keep FreeWeChat up and running despite a takedown order from the site’s hosting provider.

2 Aug 2024 | Europe and Central Asia, Germany, News, Newsletters, Russia

There is a tendency to see Russia as a huge monolithic entity with a matching ideology. This is the expansionist, imperial Russia that poisons its enemies and kidnaps their children. It is the Russia of the gulags, of Putin, Stalin and the Tsars. But there is another Russia. It is the Russia of the eight brave students who stood in Red Square in 1968 to demonstrate against the invasion of Czechoslovakia and inspired the founders of this magazine. It the Russia of the dissidents of the 1970s and the reformers of the 1990s. It is the Russia of Pussy Riot, of Alexander Livintenko, Boris Nemtsov and Alexei Navalny.

This is the Russia of Vladmir Kara-Murza, the Russian activist, politician, journalist and historian released this week in a prisoner swap with Russian spies held in the West.

Much has been made of the detention and release of American journalist Evan Gershkovich – and rightly so. The Wall Street Journal reporter has become an important symbol of the fundamental values of a free media. It is to his eternal credit that his final request before release was an interview with Vladimir Putin. We also welcome the release of Alsu Kurmasheva, a Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty journalist from the Tatar/Bashkir service.

But it is Vladimir Kara-Murza who most fully represents the dissident spirit of Russia that runs counter to the authoritarian tendency that has dominated the country for so much of its recent history.

He is often described simply as one of the fiercest opponents of Putin, But Kara-Murza is so much more than that. He is above all the keeper of the flame of the Russian dissident tradition. He, more than anyone, understands the power of this alternative version of Russian identity.

Supporters of Index interested in the subject should watch the four-part documentary series, They Chose Freedom, directed and presented by Kara-Murza in 2005. The film is edited by his wife Evgenia, who has led the campaign for his release. Two decades later it is still acts as a powerful reminder of the courage of those who spoke out against the Soviet system. It examines the roots of the dissident movement in the weekly poetry readings held in Mayakovsky Square in the 1950s. It includes interviews with the key players in the movement, including Vladminir Bukovsky, Anatoly Sharnsky and three of the participants of the Red Square demonstration of 1968, Pavel Litvinov, Natalya Gorbanevskaya and and Viktor Fainberg.

In April 2023, shortly before he was sentenced to 25 years for charges linked to his opposition to the war in Ukraine, Kara-Murza said: “I know the that the day will come when the darkness engulfing our country will clear. Our society will open its eyes and shudder when it realises what crimes were committed in its name.”.

The release comes after reports earlier this year that Kara-Murza had been transferred to a harsher prison regime and that his health was deteriorating. An image shared on Telegram (see above) by fellow dissident Ilya Yashin, also released in the prisoner swap, show Kara-Murza this morning in Germany where they will hold a press conference later today. We await news that he and family will finally be able to welcome him back to Britain, which they have made their home.

3 Jan 2020 | Magazine, News, Volume 48.04 Winter 2019

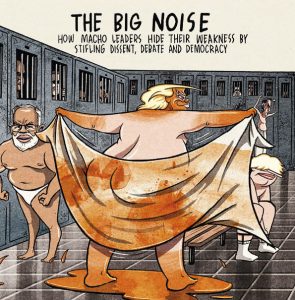

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_video link=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s-bKFo30o2o”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]What does it mean to be a man? That has been the subject of many a song and is also the subject of the winter 2019 issue of Index on Censorship magazine, where we consider how leaders are using concepts of masculinity for their political gain and our free speech loss. While you’re reading the mag, have a listen to your playlist which features artists from Bob Dylan to Taylor Swift, who are all singing, one way or another, about the problems with macho men.

Enjoy the songs below. Hopefully the outspoken lyrics of women like Lily Allen and Shania Twain will leave you feeling more empowered than despondent.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

When US President Donald Trump tweeted that he is “so great looking and smart”, Carly Simon’s classic take down of an unnamed man sprung to mind. Ditto every time we see Russian President Vladimir Putin’s appearing topless on a horse. But what are these mega egos doing to our rights? Editor-in-chief Rachael Jolley spoke to New York Times lawyer David E. McCraw about the state of media freedom in the USA under Trump.

“Macho, macho man! I want to be a macho man!” Is this what the current pack of male leaders listen to every morning? And do they also add their own words, like dominant, aggressive and infallible? For a more complete list of what they are like, how they are destroying our freedoms and how you can be a macho man too, read Rob Sears guide for the modern despot.

Brandon Flowers told NME in 2017 that the then-newly released single The Man depicted his attitude towards masculinity when The Killers started out, an attitude he now regrets. With lyrics including “don’t try to teach me, I got nothing to learn”, it’s easy to see why Flowers is glad to have grown out of such youthful notions. Unfortunately, the men who dominate world politics don’t seem to have matured out of their eagerness to be “The Man” and all that that implies. Case in point China’s Xi Jinping.

Irish rock band Thin Lizzy had a hit in 1976 with The Boys are Back in Town, a joyful ode to, well, boys being back in town. Its catchy melody means it’s still a feature on many party playlists, but delve into the lyrics and evidence of toxic masculinity is there. When the boys go out, “The drink will flow and the blood will spill, And if the boys want to fight, you better let ’em”. Kaya Genç reports on a rap collective in Turkey using music to take down that kind of ‘masculine’ behaviour men can exhibit.

While “lion man” is used with some irony by Mumford and Sons in this song, to show a man who hides his insecurities behind a facade of machismo, Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro does not appear to exhibit any irony when he refers to himself as a majestic lion surrounded by hyenas, as he did last year. Stefano Pozzebon reports on the uphill battle faced by the Brazilian press to hold this lion to account.

Bob Dylan’s moving, acoustic attacks on macho world leaders sending young people off to spill their blood on the battlefield are timeless. “When the death count gets higher, you hide in your mansion” sings Dylan in Masters of War. Somak Ghoshal reports on India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who is a fervent patriot with a strong war cry.

Macho leaders are eager to impress, whether it be to their citizens in a bid to maintain fearful respect and loyalty or fellow world leaders who they want to come across as heads of powerful states not to be underestimated. What would Canadian powerhouse Shania Twain say? If this song is anything to go by, they don’t impress her much. Arrogant intelligence, vanity and fast cars are all big no-nos, and we’d assume draconian policies and the quashing of free expression are too. It’s bad news for Tanzania’s “Bulldozer” President Magufuli.

Did Lily Allen write her song Fuck You with Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán in mind? The song takes aim at small-minded, hate-filled, racist homophobes, with lines like “So you say it’s not OK to be gay, well I think you’re just evil”, which could be one way to address a leader whose party continues to assault gay rights by promoting “family values” that exclude LGBT people.

Taylor Swift captures the inequalities between the sexes in The Man, her song about the respect she would get if she was a man for the same actions that result in criticism for a woman. Female journalists could sing the same song, often being targeted as much for their gender as for their words. Miriam Grace Go reports on Philippines’ President Rodrigo Duterte, for example, and his explicit denigration of female journalists and politicians.

No-one writes a protest song quite like Pussy Riot, the Russian feminist punk rock group. In October 2016, two weeks before Donald Trump was elected as US president, they released Make America Great Again, a dystopian vision of the USA under Trump. Lyrics include “Can you imagine a politician calling a woman dog?” Unfortunately, we don’t have to imagine this as it’s become all too real. Caroline Lees reports on how world leaders are using slurs to undermine their opponents in a trend that appears to be getting worse.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]