28 Mar 2018 | Event Reports, News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

“We must distinguish the things that are intellectually dishonest and aimed at persuading, which is traditionally called propaganda, and the things where people are trying to give you general information, which doesn’t have the absolute intention of persuading you,” said The Times columnist David Aaronovitch at a panel at the Essex Book Festival.

Aaronovitch, also Index’s chair, was discussing the role of propaganda with leading expert on the darknet and technology Jamie Bartlett and Chinese-British author Xinran, who was the first woman to have a late-night radio show in China.

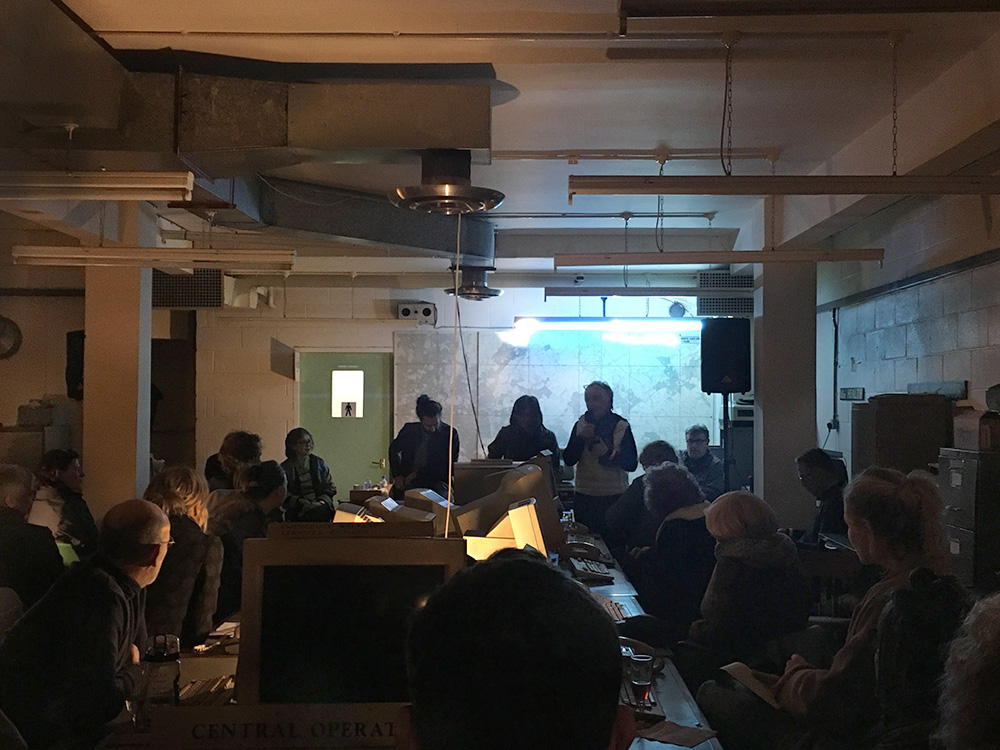

The panel, chaired by Index on Censorship magazine editor Rachael Jolley, was part of the festival’s Nuclear Option day at the Kelvedon Hatch Secret Nuclear Bunker, a twisted network of dimly lit hallways and musty rooms that lie beneath a field.

Around 75 attendees gathered on March 25 to listen to Index’s panel and attend other workshops, screenings and performances part of the festival. Everyone at the festival was free to roam the enormous bunker and walk amongst Cold War history.

Passing signs that instructed people to “use water sparingly” and dusty machines that co-ordinated evacuation procedures, attendees eventually made their way to a desk-lamp lit room and were seated at long desks with old, monochrome computers.

Looking at the current state of propaganda, Bartlett said “everything has become more emotional and gut-driven,” adding that politics has not become as informed as people had hoped, but now become “heuristic because people are just showered with information”.

Aaronovitch called the inundation of information the “age of cacophony”.

What is emerging, according to Bartlett, is a “horrible new form of soft surveillance that has encouraged a great conformity among people”.

Xinran said China’s current propaganda, especially on social media, along with party control of education and the legal system has led to “one voice” in China, despite age gaps, class, education and geographical residence.

The author talked about her past experiences with censorship and Chinese propaganda when she worked on her radio show in China. She explained that there was a list of restrictions she had to abide by, these included never mentioning the British media, Western religions or love and relationships. The author said during her show she was able to tackle subjects that were previously taboos on Chinese radio.

“My work was stopped for three months when I spoke about homosexuality,” said Xinran. “This type of censorship was very strong until 1997, but it has now escalated to constant censorship, due to social media.”

Looking at the future of propaganda and its direction, Bartlett added that he can “see much more reliance on coercive digital types of surveillance being absolutely necessary just to maintain some type of law and order in society, especially online, which could make us a much more authoritarian society”.

This led Bartlett to predict that “already authoritarian countries are going to become much more so, and already very free countries are going to become even more free to the point where it might collapse”.

He believes we are shifting to a “Huxleyan society,” which Aaronovitch called the “algorithmic society”. Both felt one big question was, who governs the algorithms?

Aaronovitch noted that it depended on who was controlling the algorithms, saying that if the EU requested that Google to reveal its algorithms, it would be problematic; however, governmental algorithms used for policing in a democratic society were essential.

With reference to the Cambridge Analytica scandal, which was mentioned numerous times during the panel, Bartlett noted that the worry over “Cambridge Analytica’s 5,000 data points on every single American doesn’t compare to what’s coming”.

“We are going to be creating a lot more data in the future,” said Bartlett. “And it is going to be shared and it is going to be used by political actors.”

Aaronovitch advised the audience that the best way to combat propaganda is to ask yourself, “‘Am I wrong?’. The point is to ensure no one is “completely blinded by initial preferences”.

Similar to Aaronovitch’s warning to predisposed biases, Xinran calls for “independent thinking,” and equated the consumption of information with eating.

“In Chinese we say you become what you eat,” said Xinran. “And your brain is the same way. You become what you are by what you believe”.

Hats off to @EssexBookFest! An incredible day at the Secret Nuclear Bunker. Brilliant discussion with @IndexCensorship, @JamieJBartlett, @DAaronovitch, @londoninsider and #Xinran, topped off with a silent disco of music banned from Estonia, with obligatory gherkins and vodka 👍 pic.twitter.com/HVtfrVDRb1 — Radical ESSEX (@RadicalEssex) 26 March 2018

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1522237614911-7109bbff-bdcf-1″ taxonomies=”2631″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

26 Mar 2018 | Awards, Fellowship, Fellowship 2018, News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/7kseuuaARZQ”][vc_column_text]The Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedoms (ECRF) is one of the only human rights organisations still operating in a country increasingly hostile to dissent and in which countless civil society organisations have been forced to close. The commission coordinates campaigns for those who have been tortured or disappeared, as well as highlighting numerous incidences of human rights abuses.

“Our main goal to achieve in the future, which is stated in our mission, is to empower individuals to acquire their rights, promote a culture of democracy in the Egyptian society, and expand human rights to every home in Egypt,” ECRF told Index. “But in the end of the day we decide to carry out with our work regardless of the challenges because if everyone is silenced this would be the ultimate gain to the current regime, and the ultimate victory to Egypt’s state of fear.”

Between August 2016 and August 2017, the ECRF documented 378 cases of enforced disappearance many of whom were students. The cases of the disappeared are not reported in the heavily censored local media, and the commission’s website and social media sites are some of the few places their plight can be publicised, reported and mapped.

The highly restrictive and repressive environment Egypt has made it increasingly difficult for the organisation to do its work.

Their website was blocked in September in government measures designed to close the organisation down, but the ECRF managed to create a parallel website to maintain their presence and engagement with the public. Twice last year ECRF’s headquarters was raided by security forces with two staff members being arrested. As a result, the staff need help dealing with the risks of being arrested, as well as dealing with the interrogation process and knowing how to protect information.

Over the past 12 months the ECRF has been fighting censorship and defending human rights in two ways. The first is through the criminal justice programme which tackles issues of torture and enforced disappearances in Egypt. It has been particularly focused on the arrest of activists who took part in demonstrations against Egypt’s agreement to cede two uninhabited islands in the Red Sea to Saudi Arabia.

Secondly, ECRF has worked on challenging censorship imposed on student associations in universities. Recently the commission launched an online platform to bring students and practitioners online to discuss a student charter related to freedom of association in universities. The platform was heavily criticised by the ministry of higher education in Cairo, which led to further condemnation of it in official media outlets.

As a direct result of the work ECRF has carried out over the past year, there has been an increased awareness of enforced disappearances, media censorship, the scale of torture, and violations of freedom of association and expression in media and universities.

“ECRF is honored to be shortlisted alongside three peer organizations/campaigns also facing severe human rights challenges in their own countries,” said ECRF. “The international recognition of ECRF’s efforts in campaigning for fundamental freedoms emboldens its members and staff in their resilience to strive for human rights and democracy in Egypt. Regardless of the winner, progress towards equal rights in Russia means progress in Egypt and progress in Kenya means progress in Iran and vice-versa.”

See the full shortlist for Index on Censorship’s Freedom of Expression Awards 2018 here.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content” equal_height=”yes” el_class=”text_white” css=”.vc_custom_1490258749071{background-color: #cb3000 !important;}”][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_custom_heading text=”Support the Index Fellowship.” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:28|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsupport-the-freedom-of-expression-awards%2F|||”][vc_column_text]

By donating to the Freedom of Expression Awards you help us support

individuals and groups at the forefront of tackling censorship.

Find out more

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″ css=”.vc_custom_1521479845471{background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/2017-awards-fellows-1460×490-2_revised.jpg?id=90090) !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;}”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1522065946315-a2955265-bb40-3″ taxonomies=”10735″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

21 Mar 2018 | Press Releases

Hoy, el Centro Europeo para la Libertad de Prensa y Libertad de Expresión (ECPMF por sus siglas en inglés) y el Instituto Internacional de la Prensa (IPI por sus siglas en inglés), lanzan una subvención de hasta 450.000€ para apoyar el periodismo de investigación y transnacional en la UE.

Hoy, el Centro Europeo para la Libertad de Prensa y Libertad de Expresión (ECPMF por sus siglas en inglés) y el Instituto Internacional de la Prensa (IPI por sus siglas en inglés), lanzan una subvención de hasta 450.000€ para apoyar el periodismo de investigación y transnacional en la UE.

http://www.ij4eu.net/

El Fondo para el Periodismo de Investigación en Europa (#IJ4EU) tiene como objetivo promover y fortalecer la colaboración entre periodistas y redacciones en Europa para la investigación de noticias de interés público, que afecten a más de un país de la UE. El Fondo pretende apoyar investigaciones periodísticas que reflejen el papel de “observador” de los medios de comunicación, y que, además, confieran al público el poder de exigir responsabilidad a aquellos que estando en el poder, hayan incumplido con sus obligaciones y funciones. De esta manera, el Fondo busca contribuir a que se mantenga la estabilidad democrática y el estado de derecho en la UE.

El Fondo será administrado por el IPI, una comunidad global de directores de medios de comunicación, redactores y periodistas, que defiende la libertad de prensa desde 1950.

Durante el 2018 aquellos equipos de periodistas de investigación transnacionales y/o medios de comunicación con sedes en al menos dos países de la UE, podrán solicitar una subvención de un máximo de 50.000€, para realizar una investigación sobre cualquier tema de interés público que afecte a más de un país de la UE.

Los proyectos presentados deberán revelar nueva información sobre el tema elegido. Podrán solicitar esta subvención equipos de investigación ya existentes o que hayan sido especialmente creados para este proyecto de #IJ4EU. También podrán participar investigaciones en curso o incompletos, siempre y cuando se cumpla con el objetivo final de terminar la investigación y proceder a su publicación. Animamos especialmente a que soliciten esta subvención, equipos de periodistas o medios de comunicación que trabajan en sedes fuera de la capital del país o de las grandes urbes o bien en países donde el periodismo de investigación resulte particularmente difícil.

El programa incluye subvenciones para todas las plataformas, prensa tradicional, digital, audiovisual, documentales y story-telling a través de múltiples plataformas o canales.

Para ser seleccionado, las propuestas deberán poder ser publicadas por medios de comunicación o plataformas reputados (y disponibles en formato publicable) en al menos dos países de la UE antes del 31 de diciembre 2018.

El plazo máximo para entregar la solicitud es el 3 mayo 2018, Día Internacional de la Libertad de Prensa. Todas las solicitudes deberán realizarse en inglés. Se deberá presentar una descripción detallada del proyecto, descripción del equipo de investigación, un plan de investigación y publicación, un presupuesto y una evaluación de riesgos.

Un jurado independiente seleccionará los proyectos que recibirán los fondos, con la intención de presentar las propuestas seleccionados el 15 de julio 2018.

Para poder realizar la solicitud y leer toda la información sobre requisitos, solicitud y proceso de selección, por favor accedan a la página web: http://www.ij4eu.net/

“El periodismo de investigación, que desempeña una función esencial en toda democracia, se encuentra, bajo presión en toda la UE”, comenta Barbara Trionfi, Directora Ejecutiva del IPI. “Apoyar económicamente a proyectos de investigación, es una manera de asegurar que temas como la corrupción, crímenes financieros, abusos de derechos humanos y daños medioambientales, lleguen al público.”

Además, añadió que “Como hoy en día, estas investigaciones no suelen estar limitadas a un único estado o país, es fundamental que los equipos periodísticos trabajen estos temas, “cruzando fronteras”: necesitan ser transnacionales”. Estamos orgullosos de que #IJ4EU nos dé esta oportunidad.

For any questions, please contact:

Javier Luque

Head of Digital Media

IPI

Email: [email protected]

Tel.: +43 1 5129011

20 Mar 2018 | Press Releases

Međunarodni institut za medije (IPI) i Europski centar za medijske slobode (ECPMF) objavili su danas novi program potpore prekograničnim projektima istraživačkog novinarstva u zemljama Europske unije vrijedan do 450 tisuća eura.

http://www.ij4eu.net/

Fond “Istraživačko novinarstvo za Europu – #IJ4EU” (Investigative Journalism for Europe) namijenjen je poticanju i jačanju suradnje među novinarima i redakcijama u Europskoj uniji na projektima u javnom interesu i od prekograničnog značaja. Fond ima za cilj podržati istrage koje odražavaju kontrolnu ulogu medija i one projekte koji omogućavaju javnosti da one na vlasti drži odgovornim za svoje postupke i dužnosti na funkcijama koje drže. Na taj način nastoji se pridonijeti održivosti demokracije i vladavine prava u EU.

Fondom će upravljati Međunarodni institut za medije (IPI), globalna mreža urednika, medijskih rukovoditelja i vodećih novinara koja se bavi zaštitom slobode medija još od 1950. godine.

Za potpore u maksimalnom iznosu od 50 tisuća eura se mogu prijaviti prekogranični timovi istraživačkih novinara iz najmanje dvije zemlje članice Europske unije, a koji će sprovesti istraživanje u javnom interesu i od prekograničnog značaja.

Predloženi projekti moraju imati za cilj otkivanje novih informacija. Jednako su poželjni već postojeći istraživački timovi, kao i oni novo oformljeni za potrebe #IJ4EU konkursa. U tijeku, ali nedovršene istrage, također ispunjavanju uvjete konkursa i mogu dobiti podršku iz ovog fonda kako bi istraga bila završena i objavljena u medijima. Posebno se potiču na prijavu timovi novinara ili redakcija koji rade izvan glavnih ili najvećih gradova u zemlji, ili u onim zemljama u kojima je istraživačko novinarstvo posebno izloženo riziku.

Program je namijenjen financiranju svih platformi, uključujući tisak, radio, TV, online medije, produkciju dokumentarnog filma i izvještavanje na kombiniranim platformama (multi-platform story-telling).

Financirani mogu biti samo projekti planirani za objavu (i dostupni u formatu koji se može objaviti) u uglednim medijima ili na platformama u najmanje dvije zemlje EU najkasnije do 31. prosinca 2018. godine.

Rok za prijave je 3. svibanj 2018. što je ujedno i Međunarodni dan slobode medija. Prijave moraju biti dostavljene na engleskom jeziku uz detaljan opis projekta, pojedinosti o istraživačkom timu, plan istraživanja i objavljivanja, budžet i procjenu rizika.

Neovisni žiri će odabrati projekte koji će biti financirani, a sklapanje ugovora o korištenju sredstava sa uspješnim kandidatima planirano je do 15. lipnja 2018.

Za prijave i više informacija o uvjetima natječaja i prijavljivanja te o postupku odabira kandidata, posjetite web stranicu fonda.

“Istraživačko novinarstvo, koje ima ključnu ulogu u bilo kojoj funkcionalnoj demokraciji, pod pritiskom je u cijeloj Europskoj uniji”, izjavila je izvršna direktorica Međunarodnog instituta za medije (IPI), Barbara Trionfi. “Pružanje financijske podrške istraživačkim projektima je način jamčenja da informacije o problemima poput korupcije, financijskog kriminala, zloupotreba ljudskih prava i uništavanja okoliša dospiju do javnosti”.

Ona je također dodala: “Budući da se takva istraživanja danas rijetko ograničavaju na jednu državu, od suštinskog je značaja da novinarske ekipe koje pokrivaju ove teme – rade preko granica. Ponosni smo što će #IJ4EU fond pružiti mogućnost za to”.

For any questions, please contact:

Javier Luque

Head of Digital Media

IPI

Email: [email protected]

Tel.: +43 1 5129011