Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

International Women’s Day is a day to remember violence against women, the education gap, the wage gap, online harassment, everyday sexism, the intersection between sexism and other -isms, and a whole host of other issues to make us realise we’ve still got a long way to go. A day to demand continued progress, and a day to pledge to work to achieve it.

But it is also a day to celebrate. To appreciate the fantastic achievements that are made every day, everywhere, by women from all walks of life. It’s a day to be grateful to the women who dedicate their lives to fighting on the front lines to protect rights vital to us all. We want to shine the spotlight on women who have stood up for freedom of expression when it’s not the easy or popular thing to do, against fierce opposition and often at great personal risk. The following eight women have done just that. We know there are many, many more. Tell us about your female free speech hero in the comments or tweet us @IndexCensorship.

Meltem Arikan

Arikan is a writer who has long used her work to challenge patriarchal structures in society. He latest play “Mi Minor” was staged in Istanbul from December 2012 to April 2013, and told the story of a pianist who used social media to challenge the regime. Only a few months after, the Gezi Park protests broke out in Turkey. What started as an environmental demonstration quickly turned into a platform for the public to express their general dissatisfaction with the authorities — and social media played a huge role. Arikan was one of many to join in the Gezi Park movement, and has written a powerful personal account of her experiences. But a prominent name in Turkey, she was accused of being an organiser behind the protests, and faced a torrent of online abuse from government supporters. She was forced to flee, now living in exile in the UK.

I realised that we were surrounded, imprisoned in our own home and prevented from expressing ourselves freely.

Anabel Hernández (Image: YouTube)

Hernández is a Mexican journalist known for her investigative reporting on the links between the country’s notorious drug cartels, government officials and the police. Following the publication of her book Los Señores del Narco (Narcoland), she received so many death threats that she was assigned round-the-clock protection. She can tell of opening the door to her home only to find a decapitated animal in front of her. Before Christmas, armed men arrived in her neighbourhood, disabled the security cameras and went to several houses looking for her. She was not at home, but one of her bodyguards was attacked and it was made clear that the visit — from people first identifying themselves as members of the police, then as Zetas — was because of her writing.

Many of these murders of my colleagues have been hidden away, surrounded by silence – they received a threat, and told no one; no one knew what was happening…We have to make these threats public. We have to challenge the authorities to protect our press by making every threat public – so they have no excuse.

Amira Osman, a Sudanese engineer and women’s rights activist was last year arrested under the country’s draconian public order act, for refusing to pull up her headscarf. She was tried for “indecent conduct” under Article 152 of the Sudanese penal code, an offence potentially punishable by flogging. Osman used her case raise awareness around the problems of the public order law. She recorded a powerful video, calling on people to join her at the courthouse, and “put the Public Order Law on trial”. Her legal team has challenged the constitutionality of the law, and the trial as been postponed for the time being.

This case is not my own, it is a cause of all the Sudanese people who are being humiliated in their country, and their sisters, mothers, daughters, and colleagues are being flogged.

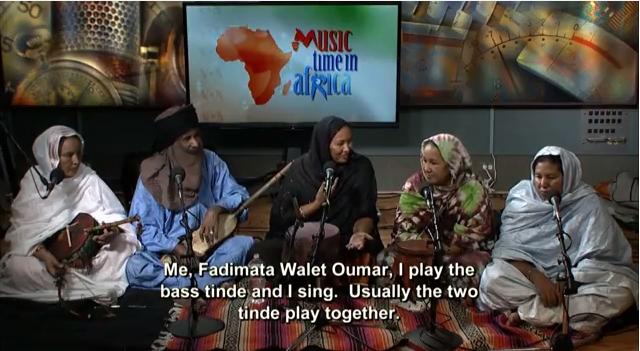

Fadiamata Walet Oumar with her band Tartit (Image: YouTube)

Fadiamata Walet Oumar is a Tuareg musician from Mali. She is the lead singer and founder of Tartit, the most famous band in the world performing traditional Tuareg music. The group work to preserve a culture threatened by the conflict and instability in northern Mali. Ansar Dine, an islamists rebel group, has imposed one of the most extreme interpretations of sharia law in the areas they control, including a music ban. Oumar believes this is because news and information is being disseminated through music. She fled to a refugee camp in Burkina Faso, where she has continued performing — taking care to hide her identity, so family in Mali would not be targeted over it. She also works with an organisation promoting women’s rights.

Music plays an important role in the life of Tuareg women. Our music gives women liberty…Freedom of expression is the most important thing in the world, and music is a part of freedom. If we don’t have freedom of expression, how can you genuinely have music?

Khadija Ismayilova

Ismayilova is an award-winning Azerbaijani journalist, working with Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. She is know for her investigative reporting on corruption connected to the country’s president Ilham Aliyev. Azerbaijan has a notoriously poor record on human rights, including press freedom, and Ismayilova has been repeatedly targeted over her work. She was blackmailed with images of an intimate nature of her and her boyfriend, with the message to stop “behaving improperly”. This February, she was taken in for questioning by the general prosecutor several times, accused of handing over state secrets because she had met with visitors from the US Senate. In light of this, she posted a powerful message on her Facebook profile, pleading for international support in the event of he arrest.

WHEN MY CASE IS CONCERNED, if you can, please support by standing for freedom of speech and freedom of privacy in this country as loudly as possible. Otherwise, I rather prefer you not to act at all.

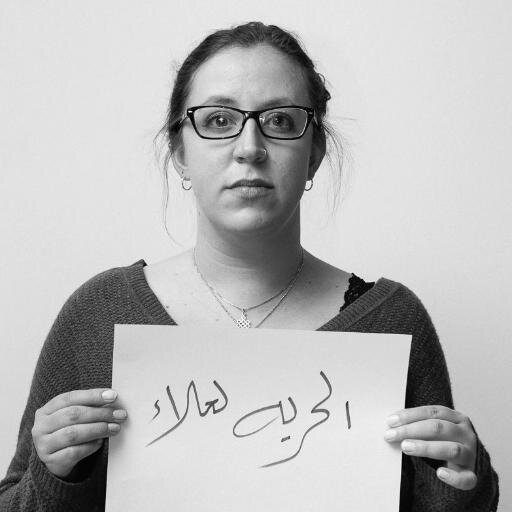

Jillian York (Image: Jillian C. York/Twitter)

Jillian York is a writer and activist, and Director of Freedom of Expression at the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF). She is a passionate advocate of freedom of expression in the digital age, and has spoken and written extensively on the topic. She is also a fierce critic of the mass surveillance undertaken by the NSA and other governments and government agencies. The EFF was one of the early organisers of The Day We Fight Back, a recent world-wide online campaign calling for new laws to curtail mass surveillance.

Dissent is an essential element to a free society and mass surveillance without due process — whether undertaken by the government of Bahrain, Russia, the US, or anywhere in between — threatens to stifle and smother that dissent, leaving in its wake a populace cowed by fear.

Cao Shunli (Image: Pablo M. Díez/Twitter)

Shunli is an human rights activist who has long campaigned for the right to increased citizens input into China’s Universal Periodic Review — the UN review of a country’s human rights record — and other human rights reports. Among other things, she took part in a two-month sit-in outside the Foreign Ministry. She has been targeted by authorities on a number of occasions over her activism, including being sent to a labour camp on at least two occasions. In September, she went missing after authorities stopped her from attending a human rights conference in Geneva. Only in October was she formally arrested, and charged for “picking quarrels and promoting troubles”. She has been detained ever since. The latest news is that she is seriously ill, and being denied medical treatment.

The SHRAP [State Human Rights Action Plan, released in 2012] hasn’t reached the UN standard to include vulnerable groups. The SHRAP also has avoided sensitive issue of human rights in China. It is actually to support the suppression of petitions, and to encourage corruption.

Zainab Al Khawaja

Al Khawaja is a Bahraini human rights activist, who is one of the leading figures in the Gulf kingdom’s ongoing pro-democracy movement. She has brought international attention to human rights abuses and repression by the ruling royal family, among other things, through her Twitter account. She has also taken part in a number of protests, once being shot at close range with tear gas. Al Khawaja has been detained several times over the last few years, over “crimes” like allegedly tearing up a photo of King Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa. She had been in jail for nearly a year when she was released in February, but she still faces trials over charges like “insulting a police officer”. She is the daughter of prominent human rights defender Abdulhadi Al Khawaja, who is currently serving a life sentence.

Being a political prisoner in Bahrain, I try to find a way to fight from within the fortress of the enemy, as Mandela describes it. Not long after I was placed in a cell with fourteen people—two of whom are convicted murderers—I was handed the orange prison uniform. I knew I could not wear the uniform without having to swallow a little of my dignity. Refusing to wear the convicts’ clothes because I have not committed a crime, that was my small version of civil disobedience.

This article was posted on March 8, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

(Image: Pseudopixels/Shutterstock)

If you live in Cuba, Iran or Sudan, and are using the increasingly popular online education tool Coursera, you are likely encounter some access difficulties from this week onwards. Coursera has been included in the US export sanctions regime.

The changes have only come about now, as Coursera believed they and other MOOCs — Massive Open Online Courses — didn’t fall under American export bans to the countries. However, as the company explained in a statement on their official blog: “We recently received information that has led to the understanding that the services offered on Coursera are not in compliance with the law as it stands.”

Coursera, in partnership with over 100 universities and organisations, from Yale to the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology to the Word Bank, offers online courses in everything from Economics and Finance to Music, Film and Audio — free of charge. Over four million students across the world are currently enrolled.

“We envision a future where everyone has access to a world-class education that has so far been available to a select few. We aim to empower people with education that will improve their lives, the lives of their families, and the communities they live in,” they say.

But this noble aim is now being derailed by US economic sanctions policy. People in Cuba, Iran and Sudan will be able to browse the website, but existing students won’t be able to log onto their course pages, and new students won’t be allowed to sign up. Syria was initially included on the list, but was later removed under an exception allowing services that support NGO efforts.

Amid clear-cut cases of censorship, peaceful protesters being attacked and journalists thrown in jail, it is easy forget that access — or rather lack of it — also constitutes a threat to freedom of expression. Lack of access to freedom of expression leads to people being denied an equal voice, influence and active and meaningful participation in political processes and their wider society.

In these connected times, it can be a simple as being denied reliable internet access. Coursera is trying to tackle this problem. They “started building up a mobile-devices team so that students in emerging markets — who may not have round-the-clock access to computers with internet connectivity — can still get some of their coursework done via smartphones or tablets,” reported Forbes.

But this won’t be of much help to students affected by the sanctions, as their access is being restricted not by technological shortcomings, but by misguided policy. Education plays a vital part in helping provide people with the tools to speak out, play an active part in their society and challenge the powers that be. Taking an education opportunity away from people in Cuba, Iran and Sudan is another blow to freedom of expression in countries with already poor records in this particular field.

Furthermore, these sanctions are in part enforced in a bid to stand up for human rights. This loses some of its power, when the people on the ground in the sanctioned countries are being denied a chance to further educate themselves, gaining knowledge that could help them be their own agents of change and stand up for their own rights.

Ironically, this counterproductive move comes not long after a Sudanese civil society group called for a change to US technology sanction.

“We want to be clear that this is not an appeal to lift all sanctions from the Sudanese regime that continues to commit human rights atrocities. This is an appeal to empower Sudanese citizens through improved access to ICTs so that they can be more proactive on issues linked to democratic transformation, humanitarian assistance and technology education — an appeal to make the sanctions smarter,” said campaign coordinator Mohammed Hashim Kambal.

Digital freedom campaigners from around the world have also spoken against the US position

Coursera says they are working to “reinstate site access” to the users affects, adding that: “The Department of State and Coursera are aligned in our goals and we are working tirelessly to ensure that blockage is not permanent.”

For now, students in Iran, Cuba and Sudan could access Coursera through a VPN network.

Hopefully this barrier to freedom of expression in countries where it is sorely needed, will soon be reversed.

This article was posted on 31 January 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

The campaign video features stories from Sudanese citizens negatively affected by the US sanctions

A group of Sudanese independent civil society members this week launched a campaign under the banner “The Sudanese Initiative to Lift US Technology Sanctions from Sudan”.

The campaign aims to educate the Sudanese public and American policy-makers about the negative impact of US sanctions on the free access to information communication technologies (ICTs) and the internet in Sudan. The launch marks a year-long advocacy effort that has included talks with US-based civil society groups and the US State Department.

The demands of the campaign is that the US government revisits its sanctions regime on Sudan, on the grounds that current sanctions negatively impact Sudanese citizens’ access to ICTs in a number of sectors, including educational institutions, pro-democracy civil society and humanitarian efforts that utilise geographic information system (GIS) technology.

Although the US announced a partial lifting of sanctions relating to educational exchange in early 2013, this targets research and the free flow of information, not personal use of communication technologies.

The objective of the campaign is to give a voice to, and learn from, the stories of a range of Sudanese citizens negatively affected by these US sanctions. In the campaign video, educators, students, crisis mappers, civil society members and technology professionals recount how US sanctions are limiting their free access to knowledge and information online.

Mohammed Hashim Kambal, the campaign’s coordinator, says: “Through talking to Sudanese citizens belonging to a wide variety of sectors it is clear that US sanctions not only hampers access to independent information but also access to knowledge and to aspects of the internet related to crowdsourcing and crisis mapping.”

He stresses, however: “ We want to be clear that this is not an appeal to lift all sanctions from the Sudanese regime that continues to commit human rights atrocities. This is an appeal to empower Sudanese citizens through improved access to ICTs so that they can be more proactive on issues linked to democratic transformation, humanitarian assistance and technology education — an appeal to make the sanctions smarter”.

For example, the Sudanese pro-democracy civil society is facing great limitations from the government and the Humanitarian Aid Commission (that oversees the work of NGOs), linked to accepting foreign funding. It is impossible to directly crowdfund from Sudanese diaspora groups because of US sanctions that don’t permit the transfer of funds to or from Sudan. They therefore have to organise crowdfunding in cooperation with active members the diaspora, who in turn collect funds and send them by hand to Sudan — a process that takes time and effort.

Additionally, crisis mapping, which was very useful during the last floods in August 2013, is limited in Sudan. Crisis mappers are not able to access or purchase tools and/or applications made by American companies, such as Google (including People Finder and Google Crisis Map) or products by Esri, an American company that specialises in GIS technology.

No Sudanese inside the country can purchase original software online. Regular citizens, as well as universities, rely heavily on pirated software that cannot be updated online automatically and is often ridden with malware.

Computer science students have reported that they are unable to obtain their certificates after taking and passing online courses affiliated with US institutions such, MITx. The reason given is that certificates are not issued for countries under comprehensive US sanctions, such as Sudan, Iran, Syria, and Cuba. Additionally, online educational websites, such as Khan Academy, Google Scholar and Audacity remain blocked to users in Sudan.

Conversations with American civil society working on net freedom, about the impact of the US sanctions has yielded positive reactions but no changes in US policy yet. In early December 2013 The New America Foundation’s Open Technology Institute issued a research paper on the topic, and recommended that the US “updates” its sanctions policy to, ”reflect the need for access to personal communications technology”.

The paper concluded that, “U.S. sanctions remain outdated” in acknowledging the role of ICTs in “enabling access to information, free expression, and political dialogue”. They also added the such sanctions “in some cases effectively aid repressive regimes that seek to control access to information within their borders with negative consequences on the civilian population.”

The Open Technology Institute’s research described the sanctions on Sudan to be “the least mature” as compared to other countries, especially Iran, which bares a lot of resemblance to Sudan in terms of political context. After Iran’s “ Green Revolution” in 2009, the US government revised its sanctions on Iran twice, once in 2010 and again in 2013, dropping restrictions on ICTs and issuing detailed instructions to US technology companies clarifying what is permitted for export to Iran and what isn’t.

There’s no reason why Sudan’s technology sanctions should be lagging behind countries like Iran and Syria. It’s time the US revisits its sanctions regime on Sudan, and shows more consideration for the importance of free access to ICTs, information and knowledge on the internet.

This article was posted on 22 January 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

Dozens of protesters in front of the Sudanese Embassy in Rome October 2013 to protest of the alleged human rights abuses in Sudan (Image Marco Zeppetella/Demotix)

In the latest magazine issue of Index on Censorship the Bishop of Bradford Nick Baines reflects on his first visit to Sudan, a country whose leader strongly believes in one religion and one language for all.

Freedom of expression is of universal importance, but its absence is sometimes more easily seen through the lens of a different culture. The familiar landscape of “home” can sometimes hinder a proper appreciation of the absence of freedoms, being outside of one’s comfort zone can heighten awareness of reality. In this article I want to approach the matter from the outside in.

Early in 2013 I visited Sudan for the first time. The diocese of Bradford has had a partnership with Sudan for 30 years, and I was linked for a decade with Anglican dioceses in Zimbabwe (in my previous post as Bishop of Croydon). I thought I could easily switch attention from one African country to another. The reality was different.

Zimbabwe is ruled by Robert Mugabe, a man so corrupt that even his own demise will not clear the path to a golden new age – there are too many people who need to be protected by power well into the future. Sudan is governed by Omar al Bashir, a man committed to the project of creating a single nation (Sudan) with a single ethnicity (Arab), a single language (Arabic) and a single religion (Islam). There is a degree of shameful incompetence about Mugabe’s manipulation of power and the consequent destruction of the Zimbabwean economy and the country’s political culture. But al Bashir knows exactly what he is doing. And he does it in the face of a serious indictment by the International Criminal Court (ICC) for genocide in Darfur: he feels untouchable

Since 99 per cent of southerners voted in 2011 for the division of Sudan into two independent states, Sudan and South Sudan, al Bashir has chosen to make the secessionists take responsibility for their choice – to some extent understandably. If they are so keen on having their own country, then they can go there… and then apply for visas to come to Sudan as foreigners. Harsh? Yes, but he could be seen to be compelling the South Sudanese to live with the consequences of their actions. Democratic choices bring consequences.

However, the real experience of this is the expulsion from Sudan of anyone deemed to originate in the south – even several generations ago. Those who remain – often because they are married to Sudanese – are prohibited from working. Apart from the human cost of this policy, the effect on the Anglican church (the Episcopal Church of Sudan, which has not divided along with the states) is an exodus of leaders, an increased dependency of those who remain on the goodwill and generosity of other Sudanese Christians. And this is happening alongside the ongoing genocide in Darfur, government violence in South Kordofan and Blue Nile state. Khartoum has had to absorb destitute migrants on an unimaginable scale.

Those displaced are almost exclusively African. They speak African languages (derogatorily referred to as “twittering” by the Arabs). They are mostly (but not exclusively) Christian.

My visit to Khartoum earlier this year ended when my wife and I left a Christian-owned guesthouse at 1am in order to get to the airport for the flight back to Manchester. Within an hour the guesthouse had been raided by the security services, all property confiscated, and all residents and guests taken in for questioning. Foreign guests were deported and the family that ran the guesthouse was removed; the father of the family is now prohibited from working. This might not sound too dramatic – especially in the light of reports from parts of the Middle East and South Asia where Christians are being targeted for violence or forced to convert to Islam – but it comes as part of a deliberate policy on the part of government to exclude Christians and force them to leave for the South. This necessarily puts pressure on Christians to keep quiet, but the bishops (in particular) continue to be unafraid to engage courageously with “the powers”.

It seems that al Bashir blames the international community for refusing to welcome him back into the fold by removing the ICC indictment after the peaceful transition to two states. Foreigners are to be removed, even when they provide essential services that cannot be provided locally. We met European medical personnel who had spent their working lives developing medical facilities in local communities, and who now found themselves thrown out, leaving medical provision severely weakened.

Why destroy social, educational and medical infrastructure simply in order to save face? Riots in September 2013 in Khartoum (initially about the removal of fuel subsidies) demonstrated that economic matters do not always serve the interests of the government of the day.

But there is a bigger question relevant beyond Sudan. How do we understand and clearly define the categories in which and through which we see political, religious and cultural phenomena? Getting the category wrong leads inevitably to miscomprehension, to a potentially dangerous misapplication of rhetoric/language… and this has political consequences.

My own diocese of Bradford has a high percentage of Muslims from south Asia. Immigration began in the mid-20th century in order to staff the textile mills of West Yorkshire. Many of Bradford’s Muslims originate from the region of Kashmiri Mirpur in Pakistan. This concentration necessarily affects how the community lives and organises in Bradford, how it is influenced by (and, in turn, influences) events back in Pakistan, and how it is understood by the non-Pakistani population in the city.

One of the first lessons I had to learn when I came to Bradford nearly three years ago was not to confuse ethnicity with religion. What might appear to be a phenomenon rooted in religious identity (certain modes of dress, for example) might actually be more appropriately understood as a cultural phenomenon that coincidentally becomes associated with religious identity. To confuse the two can be dangerous. What I have in mind here is where violence (in particular) is attributed to religion, when religious tagging is clearly a tribal badging designed to hide more cultural (or other) identity.

Examples of this can be seen in the Northern Ireland of the Troubles or the sectarian destructiveness of Lebanon. Although the categories cannot easily be extricated from one another, at least those who observe or comment on such events should have the intelligence to dig a little deeper into the categorisation of such phenomena before simplistically eliding culture and religion as if they were synonymous.

The point is that there are two dangers here: (a)that category errors lead to poor communication and confusion, and (b)that people might be reluctant to speak out on serious matters simply because they fear being accused of racism or simply getting it wrong. This doesn’t help anyone where honest and frank conversation is needed and mutual critique is essential to good relationships.

This takes us back to Sudan. It is not a simple matter – capable of easy explication or distinction – to work out what can be attributed to which category. Al Bashir’s policy seems clearly to create a political, ethnic, religious and cultural identity in which there is no place for diversity. One can assume that he is aiming at a myth of solidarity – that if everyone claims the same identity, they will buy into the same projects, have the same friends and enemies, defend the same categories and communicate in the same way. Of course, this fails to take into account the complex reality of human identity construction and how complex and diverse people interrelate and self-identify.

In one sense all this should not need to be articulated. If Muslim is blowing up Muslim in Pakistan or Afghanistan, then there is clearly more going on than mere “religion” or religious identity. Simply reporting atrocities as if they were political or cultural events (without reference to religious allegiance) is as naïve as to report on religion without reference to the ethnic, political, economic, social or cultural identities that shape religious expression.

This is not a plea for obfuscation or mitigation of religiously motivated violence. On the contrary, it is a plea for the sort of literacy that seeks to comprehend in order to know how to think about and respond to phenomena that might all-too-easily be capable of simplistic categorisation.

Language goes to the heart of this. Not only the language of explanation or reportage, but the ways in which language is (or particular languages are) seen to be totems of identities that are deemed to be inconvenient. In Zimbabwe identity is tied up inextricably with language: the Shonaspeaking government has demonstrated in past violence what it thinks of the Ndebelespeaking Matabele. In Sudan African languages – mostly spoken by Christians of African (rather than Arabic) origin – are being derided and squeezed out. This is one reason why some churches in Sudan put such high value on keeping their own languages alive, teaching them to both children and adults, working hard (with pitiful resources) to reserve their means of communication as an integral element of cultural and religious identity. Language is as much part of individual and common identity as is skin colour, and nobody should be compelled to lose their native tongue.

One of the most penetrating verses of the Old Testament is found in the book of Proverbs. Seized upon by opponents of Hitler during the 1930s and 1940s in Germany, it demands that we “open our mouths for the dumb” – that is, that those who have a voice must keep alive the songs and language of people whose voice is silenced by the exercise of corrupt power. The moral demands of this are clear here also. But, for that voice to be heard and understood, it is essential that intelligent consideration is given to ensuring that the categories of speech and identification are kept as accurate as possible.

Responding to religious phenomena as if they were merely “cultural” is as dangerous and misplaced as eliding all cultural phenomena as merely “religious” – and runs the risk of stopping people speaking truthfully and accurately when religion is the root of violence or cultural violence seeks to hide behind a religious facade. The world is more complex than that. We can and must do better.