18 Oct 2018 | Magazine, News and features, Volume 47.03 Autumn 2018

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”103276″ img_size=”700×500″][vc_custom_heading text=”Anonymous, threatening letters are being sent to UK homes to try to stop activities that the Chinese government disapproves of. Jemimah Steinfeld investigates” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][vc_column_text]Benedict Rogers was surprised when he received a letter at his London home addressed simply to “resident”. The letter was postmarked and stamped from Hong Kong. He opened it and was promptly greeted by a photograph of himself next to the words “watch him”. It had been sent to everyone on his street, telling them to keep an eye on Rogers.

Rogers was just one UK resident who has spoken to Index about receiving threats after doing work that the Chinese government would rather did not happen.

While no one is 100% sure who is behind the letters, or if they are connected to the Chinese government, the senders certainly have enough power to be able to access personal information, including home addresses. The recipients are always Hong Kong’s leading advocates of free expression.

Rogers, who founded human rights NGO and website Hong Kong Watch in 2017, described what it was like to receive the letter and to realise that people nearby had received it, too.

“It obviously is an uncomfortable feeling knowing that, basically, they know where I live. They’ve done the research and I don’t quite know what is going to happen next,” he said.

“The [neighbours] I spoke to were very, very sympathetic. And they were actually not neighbours who knew me personally, so I was initially concerned about what on earth they were going to make of this. But they saw immediately that it was something very bizarre… they’d never experienced anything quite like it before.

“And then [in June] my mother received a letter sent to her own address. It specifically said to my mother to get me to take down Hong Kong Watch.”

This was the first tranche of letters to arrive. A month later, more were sent to Rogers and his neighbours. They had all the hallmarks of coming from the same sender and included screenshots of Rogers at a recent Hong Kong Watch event.

“I am writing to give you a quick update about your neighbour, the Sanctimonious Benedict Rogers and his futile attempt to destabilise Hong Kong/China with his hatred of the Chinese people and our political system,” the letters read.

Rogers, who lived in Hong Kong between 1997 and 2002, has already encountered problems arising from his promotion of democracy there. In November last year, he was refused entry to the city on arrival at the airport and put on a flight out. The latest letters referenced this November incident, saying that being “barred from entering the Chinese territory” has not “deterred or humbled him to realise the consequences of interfering in the internal politics and nature” of another society.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”It obviously is an uncomfortable feeling knowing that, basically, they know where I live” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]The abduction of booksellers, the assault on newspaper editors, the imprisonment of pro-democracy activists all show the dangers of challenging Beijing’s line in Hong Kong. It appears that China is now extending its reach further overseas, sending a message that you are not safe outside the country. Hong Kong publisher Gui Minhai was kidnapped in Thailand in 2015, after reportedly preparing a book on the love life of Chinese President Xi Jinping. These letters to UK residents are further proof of the limits some will go to in order to silence those who want to promote autonomy and basic freedoms in Hong Kong.

Evan Fowler is a resident of Hong Kong who is moving to the UK because his life, he says, has become impossible in his home town. We are sitting in a cafe in central London while he recounts intimidation tactics that have been used to try to silence him. It’s a tough conversation.

Fowler wrote for a very popular Cantonese news site, House News, which was forced to close down in 2014. Its main founder was abducted and tortured, and Fowler says he has suffered periods of severe depression since. He, too, recently received letters to his home in Hong Kong, and is aware of several people who have received them in the UK.

“The interesting thing about these letters is that, in my understanding, the letters all contain similar phrases – no direct threats are made, but [there is] an identification of you as an enemy of the Chinese people,” he said.

Fowler speaks of how “the threat level has been increasing in Hong Kong” and says that “Hong Kong pre-2014 is different from Hong Kong after”.

“It’s a city that is being ripped apart,” he said.

Another recipient of the letters, Tom Grundy, is editor-in-chief and co-founder of Hong Kong Free Press, based in the city. His mother, who lives in the UK, also received a letter late last year.

“I am slightly concerned that Tom has taken to a path that has become unsavoury and unhelpful to the some (sic) of the people of Hong Kong,” the letter read. “However, in politics, when one does not know one’s enemies clearly, one could get hurt.”

It added: “I and many people would really regret if something happened to Tom in the next few years.”

When Index spoke to Grundy, he said he was concerned about how they found the addresses of family members, and that the incident had upset his mother.

But, having reported it to the Hong Kong police, he is hopeful that it has been dealt with – the letters stopped immediately upon doing so.

“Journalists aren’t walking around Hong Kong fearing that they are going to be plucked from the streets,” he said.

“Hong Kong has had the promise of press freedom and it’s been a bastion of press freedom for Asia for decades, and NGOs like you and us are concerned and we raise the alarms because we want the civil liberties and freedom to be maintained.”

This does not mean that Grundy doesn’t have his concerns about press freedoms in Hong Kong. It’s just that, for now, the letters aren’t as much of a concern compared with other things happening in the city, such as the as yet unresolved kidnapping of the booksellers, for example.

But for others, these letters have been hard to shake off. Will they have their desired silencing effect? The picture is complicated.

“I think it’s highly unlikely that they would try any physical harm in London, so I don’t feel scared,” said Rogers, adding that it is, however, “not a pleasant feeling”. At the same time, he is keen to stress that he won’t be silenced.

“It’s actually, if anything, made me more determined to carry on doing what I’m doing because I don’t think one should give in to tactics like this.”

His view is echoed by Catherine West, a British MP who is on the board of Hong Kong Watch.

“This sort of intimidation is very unpleasant,” she told Index. West is aware of the two incidences connected to Rogers and encouraged him to go to the UK police.

“Whoever is doing this should realise this will only embolden us to promote human rights,” she added.

Speaking of Hong Kong specifically, West said: “We would like to be sure that freedom of expression is not curtailed and that young people in particular can express it without being curtailed.

“We feel it’s important for parliamentarians around the world to be involved, to be standing in solidarity with one another.”

Jemimah Steinfeld is deputy editor of Index on Censorship[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Jemimah Steinfeld is deputy editor of Index on Censorship. This article is part of the latest edition of Index on Censorship magazine, with its special report on The Age Of Unreason.

Index on Censorship’s autumn 2018 issue, The Age Of Unreason, asks are facts under attack? Can you still have a debate? We explore these questions in the issue, with science to back it up.

Look out for the new edition in bookshops, and don’t miss our Index on Censorship podcast, with special guests, on Soundcloud.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”The Age Of Unreason” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2018%2F09%2Fage-of-unreason%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The autumn 2018 issue of Index on Censorship magazine explores the age of unreason. Are facts under attack? Can you still have a debate? We explore these questions in the issue, with science to back it up.

With: Timandra Harkness, Ian Rankin, Sheng Keyi[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”102479″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2018/09/age-of-unreason/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

3 Oct 2018 | Event Reports, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”103062″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]“Critical thinking is important, but we should also be teaching scientific literacy and political literacy so we know what knowledge claims to trust,” said Keith Kahn-Harris, author of Denial: The Unspeakable Truth, at a panel debate during the launch of the autumn 2018 edition of Index on Censorship.

The theme of this quarter’s magazine, The Age of Unreason, looks at censorship in scientific research and whether our emotions are blurring the lines between fact and fiction. From Mexico to Turkey, Hungary to China, a whole range of countries from around the globe were covered for this special report, featuring articles from the likes of Julian Baggini and David Ulin. For the launch, a selection of journalists, authors and academics shared their thoughts on how to have better arguments when emotions are high, while exploring concerns surrounding science and censorship in the current global climate.

Aptly taking place at the Royal Institution of Great Britain, the historical home of scientific research for 14 Nobel Prize winners, Kahn-Harris was joined by BBC Radio 4 presenter Timandra Harkness and New Scientist writer Graham Lawton. The discussion was chaired by Rachael Jolley, editor of Index on Censorship magazine.

“Academics and experts are being undermined all over the world,” said Jolley, setting the stage for a riveting conversation between panellists and the audience. “Is this something new or something that has happened throughout history?”

When Jolley asked why science is often the first target of an authoritarian government, Lawton proposed that the value of science is that it is evidence-based and subsequently “kryptonite” to what rigid establishments want to portray. He added: “They depend extremely heavily on telling people half-truths or lies.”[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”103066″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]Harkness led a workshop highlighting the importance of applying critical thinking skills when deconstructing arguments, using footage of real-life debates, past and present, to investigate such ideas. Whether it was the first televised contest between presidential candidates John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon in 1960, or a dispute between Indian civilians over LGBT rights earlier this year, a wide variety of topics and discussions were analysed.

Examining a debate between 2016 presidential candidates Donald Trump and Hilary Clinton, Harkness asked an audience member his thoughts. Focusing on Trump’s approach, he said: “He’s put up a totally false premise which is quite a conventional tactic; you put up something that is not what the other person said, and then you proceed to knock it down quite reasonably because it’s unreasonable in the first place.” Harkness agreed. “It’s the straw man tactic”, she said, “where you build something up and then attack it.”

Panellists began discussing how to argue with say those who deny climate change, with Kahn-Harris contending that science has become enormously specialised over the past centuries, which means people cannot always debunk uncertain claims since they are not specialists. He said: “There’s something tremendously smug about the post-enlightenment world.”

Harkness said “robust challenges” should be sought-after rather than silencing those who share different views, while Lawton added that “storytelling and appealing to emotions are perfectly valid ways of arguing.”

For more information on the autumn issue, click here. The issue includes an article on how fact and fiction come together in the age of unreason, why Indian journalism is under threat, Nobel prize-winning novelist Herta Müller on censorship in Romania, and an exclusive short story from bestselling crime writer Ian Rankin. Listen to our podcast here. Or, try our quiz that decides how prone to bullshit you are…[/vc_column_text][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1538584887174-432e9410-24f0-4″ taxonomies=”8957″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

10 Sep 2018 | Magazine, News and features, Volume 47.03 Autumn 2018

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Using fiction and stories to influence society is nothing new, but facts are needed to drive the most powerful campaigns, argues Rachael Jolley in the autumn 2018 Index on Censorship magazine” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][vc_column_text]

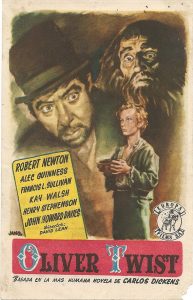

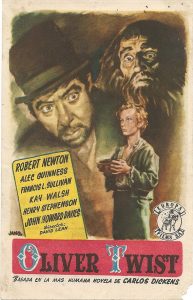

Poster for the 1948 film adaptation of Charles Dickens Oliver Twist (Photo: Ethan Edwards/Flickr)

My friend’s dad just doesn’t believe that UK unemployment levels are incredibly low. He thinks the country is in a terrible state. So when I sit down and say unemployment in 2018 is at 4.2%, the joint lowest level since 1971, he doesn’t really argue. Because he doesn’t believe it.

Well, I say, these are the official figures from the Office for National Statistics. His response is: “Hmm.” Clearly my interjection hasn’t made any difference at all.

He raises an eyebrow to signify, “They would say that, wouldn’t they?”.

This figure, and the picture it sketches, doesn’t chime with his national view, which is that things are very, very bad. And it doesn’t chime with the picture sketched in the newspaper that he reads every day, which is that things are very, very bad.

So, consequently, whatever facts or figures or sources you might throw at him to prove otherwise, nothing makes an impression on him. He believes that the world is the way he believes it is. No question.

Like many people, my friend’s dad reads news stories that reflect what he believes already, and discards stories or announcements that don’t.

And in itself, that is nothing new. For decades people have trusted their neighbours more than people far away. They have read a newspaper that echoed their political persuasion, and sometimes they have felt that the society they lived in was worse than it used to be, even when all the indicators showed their lives had improved.

Often humans believe in ideas by instinct, not because they are presented with a graph. In 2005, Drew Westen, a professor of psychology and psychiatry at Emory University, in Atlanta, USA, published The Political Brain. In it, he argued that the public often made decisions to support political parties based on emotions, not data or fact.

The book struck home with activists, who tried to utilise Westen’s thinking by changing the way they campaigned. Politicians had to capture the public’s hearts and minds, Westen said. He talked about the role of emotion in deciding the fate of a nation and gave examples. When US President Lyndon Johnson proposed the 1965 Voting Rights Act, which outlawed racial discrimination at the US ballot box, he used personal stories to make his points stronger, said Westen, adding that this was a powerful tool. In doing so, Westen was ahead of his time in acknowledging just how strongly humans value emotion, and how an emotional action can be driven by feeling and desire rather than the latest data from a governmental body.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”The articulation of ideas through emotional stories, though, is really no different from Charles Dickens sketching the harsh world of the children in workhouses in Oliver Twist” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Westen used his thesis to show why he felt US Democratic candidates Al Gore and Michael Dukakis had failed to get elected, and why George W Bush had. Bush, he felt, was in touch with his emotional side while Dukakis and Gore tended to turn to dry data and detail.

That argument about how emotional beliefs or gut feelings are being used to influence important decisions has raced up the agenda since President Donald Trump arrived in the White House, the UK voted for Brexit and with the use of emotionally driven political campaigns to shift public opinion in Hungary and Poland.

Suddenly this question of why people were responding to appeals to emotion and dismissing facts was the debate of the moment. In many ways this is nothing new but the methods of receiving ideas and information are different. Now we have Facebook and Instagram posts, and zillions of tweets to spin and challenge.

One part of it, the articulation of ideas through emotional stories, though, is really no different from Charles Dickens sketching the harsh world of the children in workhouses in Oliver Twist, or Victorian writer Charles Kingsley’s story The Water Babies. Kingsley’s tale of child chimney sweeps helped to introduce the 1864 Chimney Sweepers Regulation Act, which improved the lives of those children significantly.

Fictional stories, like these, have always played a part in changing attitudes, but also draw on reality. Dickens and Kingsley were outraged by the living and working conditions they saw, so they chose to try to effect change by using fictional stories to engage a wider public. And personal stories are also used to illuminate wider factual trends. For years journalists have used a case study as an explainer for something more detailed.

Facts and figures undoubtedly must have a role. Even when it appears there is public resistance to acceptance of data, something such as the fact that if you wear a seatbelt when driving a car you will have a better chance of surviving an accident becomes an accepted truth over time. Public information and published statistics clearly play a part in that shift.

That’s why it is so vital that public access to information is protected and that incorrect facts are challenged. This month, 28 September is the international day for universal access to information, something that concentrates the mind when you look at places where access is limited, or where government data is skewed to such a level that it becomes almost pointless.

Journalists reporting in countries including Belarus and the Maldives tell us their quest for trustworthy sources of national information are almost impossible to find as their governments refuse to respond to media requests or release untrue information. Officials also use smear tactics to undermine reporters’ reputations, so their accurate journalism is not believed. Governments know that by keeping information from the media they hamper a journalist’s ability to report, and in doing so may keep a scandal from the public. If facts and data didn’t make a difference, those governments would have no reason to restrict access.

Freedom to access information goes hand in hand with freedom of the media and academic freedom in creating an open democratic society. But at Index, we constantly see signs of governments, and others, trying to prevent both access to facts and to suppress writing about inconvenient truths.

In this issue of the magazine, we explore all aspects of this struggle to balance facts and emotion, the quest to find the truth, how we are influenced, and why arguments, debates and discussions are so vital.

There’s lots to read, from Julian Baggini’s piece (p24) on why people might fear a disagreement to tips on how to have an argument from Timandra Harkness (p31). Then there’s Martin Rowson’s Stripsearch cartoon (p26). Our interview with British TV presenter Evan Davis discusses whether lies tend to be found out over time, and the likelihood that people will select facts that support their political position.

What’s it like to be a scientist in the USA right now? Michael Halpern from the Union of Concerned Scientists in the USA says scientists are suddenly getting active to push back against a political climate attempting to take the factfile away from important government departments.

Almost every day a new story pops up outlining another attack on media freedom in Tanzania, and in this issue Amanda Leigh Lichtenstein reveals how bloggers are being priced out of the country (p70) as the government uses new fees to close down independent voices.

Then there’s Nobel prize winner Herta Müller on her experiences of censorship as a writer living in communist Romania (p67), and Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe’s poems written in prison (p86).

And finally, look out for our Banned Books Week events coming up at the end of September – find out more on the website. You’ll also find the magazine podcast, with interviews with broadcaster Claire Fox and Tanzanian blogger Elsie Eyakuze, on Soundcloud, and watch out for your invitation to the upcoming magazine event at the Royal Institution in October.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Rachael Jolley is editor of Index on Censorship. She tweets @londoninsider. This article is part of the latest edition of Index on Censorship magazine, with its special report on The Age Of Unreason.

Index on Censorship’s autumn 2018 issue, The Age Of Unreason, asks are facts under attack? Can you still have a debate? We explore these questions in the issue, with science to back it up.

Look out for the new edition in bookshops, and don’t miss our Index on Censorship podcast, with special guests, on Soundcloud.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”The Age Of Unreason” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2018%2F09%2Fage-of-unreason%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The autumn 2018 issue of Index on Censorship magazine explores the age of unreason. Are facts under attack? Can you still have a debate? We explore these questions in the issue, with science to back it up.

With: Timandra Harkness, Ian Rankin, Sheng Keyi[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”102479″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2018/09/age-of-unreason/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]